China's Shrinking Exports Make Deflation Unavoidable

Some Cans Cannot Be Kicked Down The Road

While the most urgent headlines on China swirl around their slowly collapsing property bubble, real estate is not the only economic crisis China faces.

China, long touted as the world’s factory, is shedding exports, shedding imports, and shedding the growth attendant on both.

China reported a smaller-than-expected decline in exports in September from a year ago, while imports missed, according to customs data released Friday.

In U.S.-dollar terms, exports fell by 6.2% last month from a year ago. That’s less than the 7.6% drop forecast by analysts in a Reuters poll.

Imports also fell by 6.2% in U.S.-dollar terms in September compared to a year ago — slightly more than the 6% decline expected by the Reuters poll.

When the good news on exports is that the news sucked less than expected, that is a sure sign that the news is not at all good. And it isn’t.

Unlike the property bubble, which may yet see disaster held off by a massive government bailout, shrinking exports are not something Beijing can easily reverse via stimulus. There is no bailout for lack of interest abroad in Chinese goods.

Shrinking exports are an economic can China can’t kick down the road.

While China has succeeded in improving its exports to the European Union, its exports to the United States—its largest single-country customer—dropped precipitously.

For the first three quarters of the year, China’s exports to the U.S. fell by 16.4%, while imports dropped by 6% during that time.

Russia was the only major country or region in the Chinese customs agency’s report that showed growth in both exports and imports for the first three quarters of the year from a year ago.

That Russia is showing increased exports from China is unsurprising—with the sanctions regime over the war in Ukraine, Russia has few places to shop for goods except China, and even fewer places to sell its oil.

Despite the increase in Russia trade, overall China’s exports and imports have not been sufficient to overcome the fallout of China’s collapsing property bubble.

China’s recovery from the pandemic slowed in the last few months, dragged down by a slump in the massive real estate sector.

The International Monetary Fund this week trimmed its 2023 China growth forecast to 5% from 5.2%, while maintaining a global growth forecast of 3% for the year. The world economy grew by 3.5% last year.

Nevertheless, the corporate media still is doing its best to put lipstick on the China economic pig by talking up the “slowing” of the shrinkage.

China's exports and imports shrank at a slower pace for a second month in September, customs data showed on Friday, adding to the recent signs of a gradual stabilisation in the world's second-biggest economy thanks to a raft of policy support measures.

Exports and imports “stabilizing” after significant decline is not the sign of a stable economy, it is the sign of at best a stagnant economy. Depending on the other sectors of the economy, stablizing exports and imports are in fact more confirmation that China’s economic choices remain either deflation or stagflation.

Imports and exports both declined by less than some experts had forecast, but the overall trend is unmistakable: The world’s factory is taking in fewer inputs and fewer raw materials and producing fewer goods. When that happens month after month, as it has, that is a trend that spells deflation and economic contraction.

That was the case last month, and it remains the case this month.

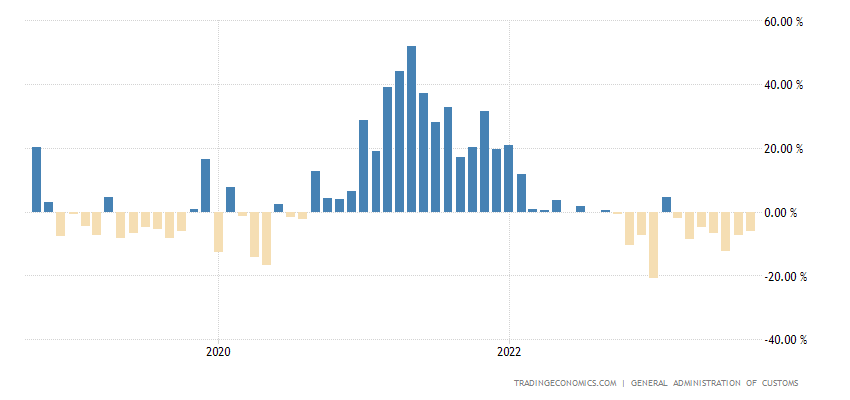

Yet the problem is not merely China’s exports last month nor its imports this month. As China’s own data illustrates, China’s overall exports have been declining since late 2021 and early 2022.

China’s best export months in reent years have been during the time when Chinas was locked down in Zero COVID. This is made particularly clear by looking at the year on year shifts in exports for China.

Let that sink in: China exported more under lockdown than it is doing now that the lockdown is lifted and people are able to move about and go to work once more. This is the exact opposite of what we would expect to see, and what the “experts’ believed we would see.

Imports peaked at about the same time as exports.

As with exports, the year on year shifts in imports illustrate how much China’s industrial base has been slowing in recent months. Without imports, without raw materials for inputs, China has nothing with which to make goods for exports.

Again, China did more business under Zero COVID than it has done since. That alone is a major red flag that China’s economy is ailing.

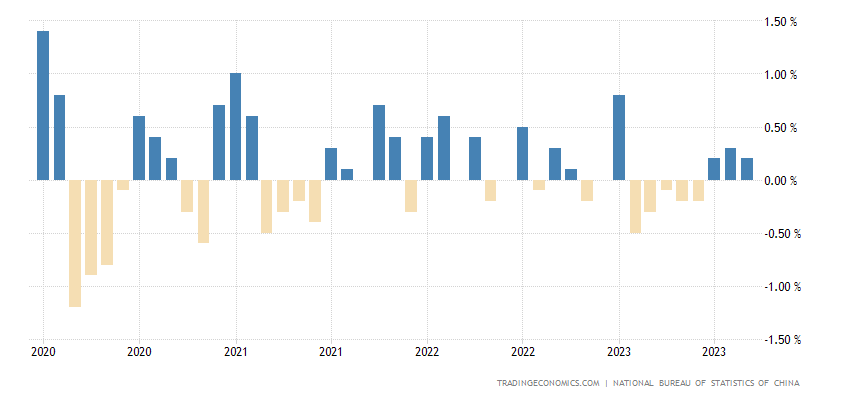

China’s export engine is not the only place that continues to falter. While technically remaining out of the negative realm that would signify outright deflation, China’s Consumer Price Index again failed to impress.

China's consumer prices faltered and factory-gate prices shrank slightly faster than expected in September, with both indicators showing persistent deflationary pressures in the world's second-largest economy.

The consumer price index (CPI) was unchanged in September from a year earlier, data by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) showed on Friday, missing the forecast of a 0.2% gain in a Reuters poll. CPI rose 0.1% in August.

Much as with the PMI data, China’s consumer prices have been either slowing or shrinking on a year on year basis since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While on a month on month basis consumer prices have shown some growth over the past three months, inflation is still hovering around that zero level that is often taken as an indicator the eeconomy is either stagnant or declining.

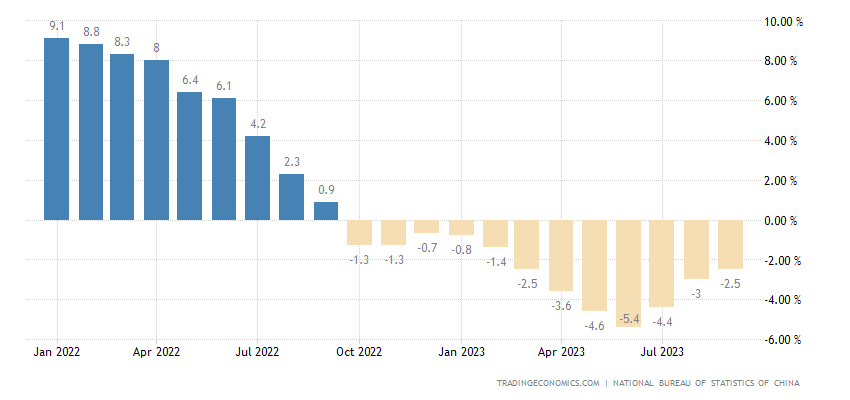

Nor is the near term outlook likely to be much better, as factory gate prices—the precursor and leading indicator for consumer prices—are showing even more weakness than consumer prices.

The producer price index (PPI) fell 2.5% from a year earlier, the 12th straight month in negative territory though the pace of decline slowed from August. Economists had predicted a 2.4% fall in September.

When factory gate prices are in deflation for a full year, that’s not a good sign—and factory gate prices in China have been in deflation for 12 straight months.

It is telling of the problems facing the Chinese economy that factory gate prices are another area which peaked at the height of the Zero COVID lockdown in 2022.

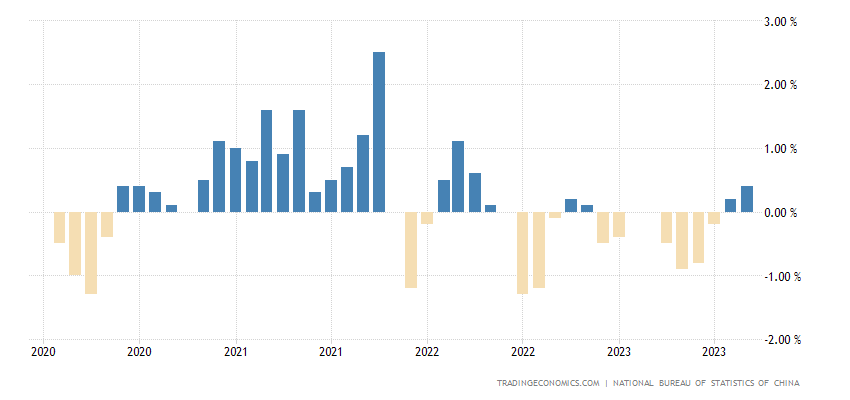

Even the monthly factory gate price changes do not show any significant demand pressure.

What they do show is that China’s best month for factory gate price improvement was in mid-2021. Since then, factory gate prices have been weakening steadily.

Put simply, China is just not seeing adequate demand pressure for its goods, not internally nor externally. Where there is no demand it is very hard to have any economic growth of consequence.

Nor are the problems merely fallout either from the COVID pandemic or China’s insane Zero COVID lockdown policies.

If we look farther back, before 2020, we see signs of encroaching weakness within China’s factory gate price metrics.

Even the month on month shifts pre-COVID show China’s economy weakening significantly.

Factory gate deflation in late 2019 was well before the world had even contemplated COVID, much less began locking down because of it.

China’s economic weaknesses likewise run much deeper than the COVID pandemic or any fallout from it. China has been heading into economic crisis for years.

The price index red flags are further confirmed by China’s Purchasing Manager Indices.

Although China’s Manufacturing PMI registered expansion for the first time in months, the new order metrics continue to show contraction instead.

Shrinking new orders, particularly new orders for export, do not augur well for future growth in export, which in turn does not augur well for any sustained uptick in factory gate prices.

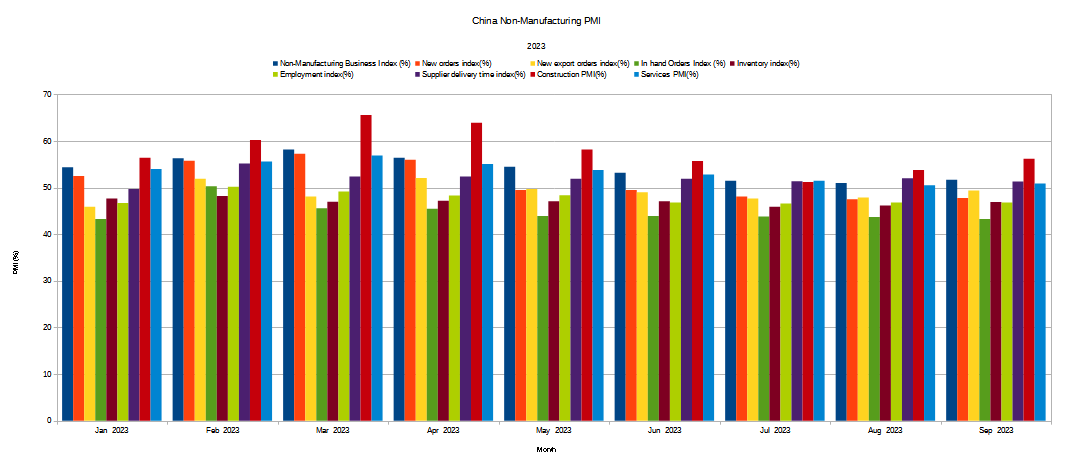

China’s Non-Manufacturing PMI is likewise showing contraction for new orders, indicating that the future for the services side of the economy is not great.

These are all signs of weakness that are outside the real estate sector. The manufacturing weaknesses does not augur well for the future of real estate construction, but those weaknesses are still an added complication to the real estate crisis—they are not a cause of it.

As I noted in August, China’s economy is a “perfect storm” of crises.

In September, the storm continued to gather strength.

Some economic dilemmas can be delayed. Indeed, the primary purpose of most economic stimulus is to kick those economic crisis cans down the road, under the questionable logic that it is better to deal with them tomorrow than it is to have them today.

Yet there is no stimulus measure for lack of export demand. There is no stimulus that will power the imports necessary for the manufacture of those exports if there is no demand overseas. China, as is true of all countries, cannot compel foreign countries to buy more Chinese goods or make more use of Chinese services. Ultimately, no one has that manner of market power.

By the same token, it is impossible to stimulate demand when the average Chinese household is already uncertain because of the collapsing property markets and the wealth destruction being inflicted on Chinese consumers as a direct consequence. Export weakness and consumer price weakness are not problems for which the day of reckoning can be postponed.

Regardless of Beijng’s plans and objectives, that day of reckoning is drawing closer day by day, and it will not be denied. Whether this becomes Japan-style deflation or the stagflation of a “rolling recession”, Beijing will still be confronted with the ramifications of a shrinking economy sooner than it would like.

Neither the export economic can nor the consumption economic can is able to be kicked down the road any further. If Beijing has any plans for dealing with lack of demand both onshore and offshore for Chinese goods, the time to implement those plans is now.