Once again, China’s latest round of economic data has failed to live up to China bull expectations.

Once again, China’s economic indicators are signaling either deflation or stagflation.

Once again, China’s economic indicators are not signaling economic recovery, economic expansion, or a future of economic prosperity.

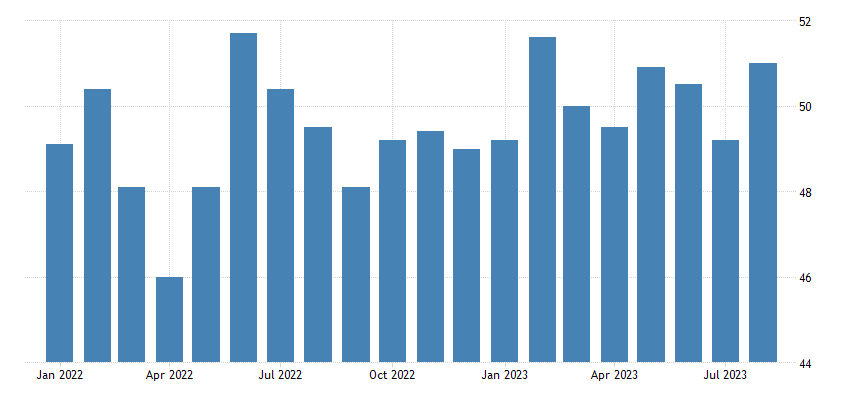

A private survey of business activity in China’s services sector fell to its lowest level in eight months in August, as a flurry of economic stimulus measures seemed unable to reignite consumption demand.

The Caixin China general services purchasing managers index (PMI) slipped to 51.8 last month from 54.1 in July, according to data released Tuesday by Caixin Media and S&P Global. A reading above 50 indicates expansion, while anything below that level shows contraction.

“The slowdown in business activity coincided with a weaker increase in overall new business. New orders increased modestly, and at a pace that was below the average seen for 2023 to date,” Caixin and S&P said in a statement.

China’s economic dilemma is not merely a collapsing property sector, or Country Garden’s ongoing flirtation with debt default and disaster. China’s economy is slumping quite literally across the board, and the dramatic decline in the Caixin PMI is but the latest examplar of China’s subpar economic metrics.

There simply is no good way to spin the data. China’s economy seems stuck in what is becoming a perma-slump. The stimulus efforts Beijing has deployed thus far have been ineffective, and the result is now even the services PMI data is indicating a deepening deflationary cycle is underway.

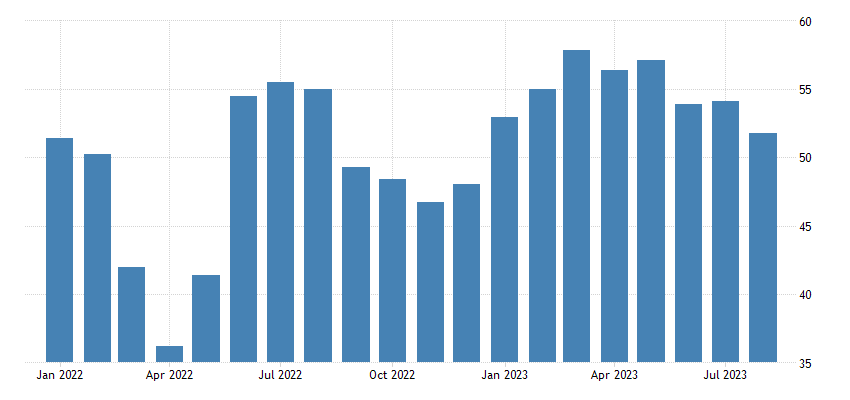

The Caixin Services PMI peaked earlier this year, right after the end of the Zero COVID lunacy.

To the extent that China experienced a “recovery” and a “reopening” after ending Zero COVID in December 2022, by February that burst of positive economic energy had been spent and dissipated.

Even the Caixin Manufacturing PMI data is problematic at best, flitting between expansion and contraction almost monthly.

The Caixin Composite PMI fares little better. It has managed to stay in expansion territory all year, but at times just barely, and for the past few months it has been showing signs of weakening again.

The Caixin PMI data is typically more optimistic than the official National Bureau of Statistics data. When the Caixin PMI metrics have a pessimistic undertone, China’s economy is definitely not prospering.

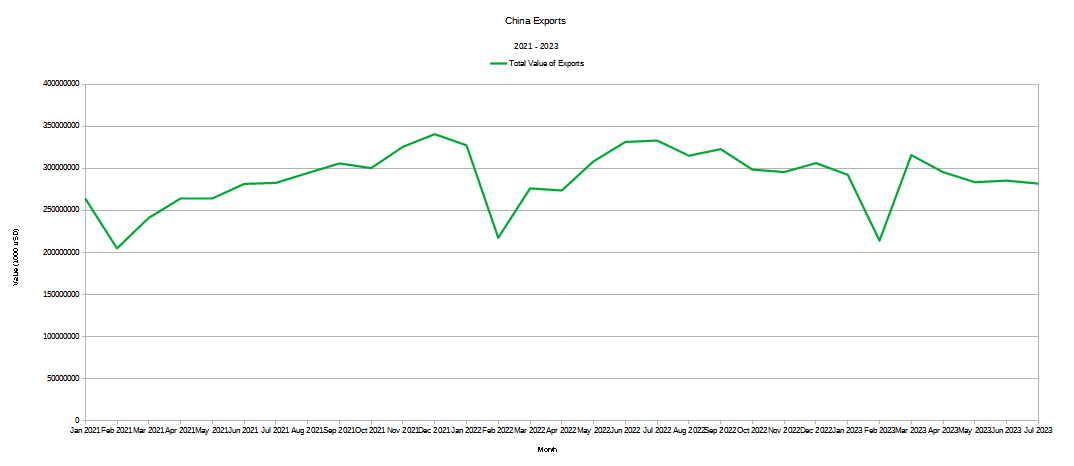

Nor is the bad news confined to PMI metrics. China’s imports and exports have both declined yet again.

China reported Thursday another monthly decline in imports and exports, albeit less steep than expected.

Exports in U.S. dollar terms fell by 8.8% in August from a year ago. That’s better than the 9.2% drop forecast by a Reuters poll.

Imports in U.S. dollar terms fell by 7.3% in August from a year ago, better than the 9% decline forecast by Reuters.

Imports have now fallen every month in 2023 from the year-ago period. Exports have fallen year-on-year for every month since April as global demand for Chinese goods wanes.

Imports and exports both declined by less than some experts had forecast, but the overall trend is unmistakable: The world’s factory is taking in fewer inputs and fewer raw materials and producing fewer goods. When that happens month after month, as it has, that is a trend that spells deflation and economic contraction.

Upon closer inspection, we see that, in reality, China’s exports peaked in December of 2021, at $340,498,780.

China’s exports have been slowly declining ever since. Whether this is a reflection of a global slump in demand or a geopolitical shifting away from China as a supplier, the end result is the same: China has been exporting less and less each month this year. There is no scenario where that is a favorable economic trend.

Nor is the situation much different on the import side. China’s imports peaked in November of 2021, at $253,813,881. The trend since has been a marginal decline.

In many ways, this makes sense. If China is exporting less, it needs to import fewer raw materials. Yet this decline also suggests China is importing fewer consumer goods from abroad for its own internal markets. In both interpretations, the end result is the same: China is importing less, and therefore overall is consuming less. As with exports, there is no scenario where this is a favorable economic trend.

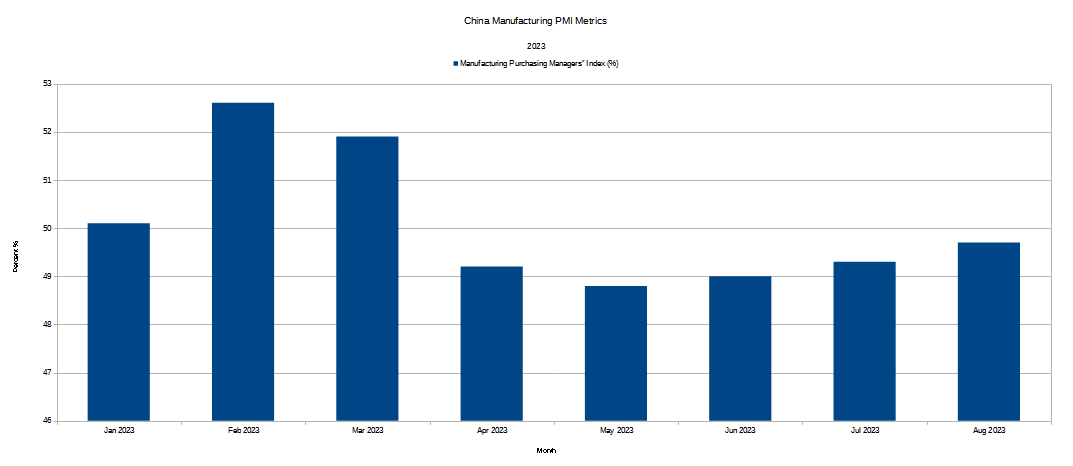

Nor is there any relief to be found in China’s “official” PMI statistics.

After a brief interlude of expansion at the beginning of the year, China’s Manufacturing PMI has been showing contraction every since.

Nor is it contracting just this year. From the fall of 2021, China’s official Manufacturing PMI metric has had repeated contractionary cycles.

The signal is that China’s manufacturing activity is shrinking, and that this is not a new or temporary trend.

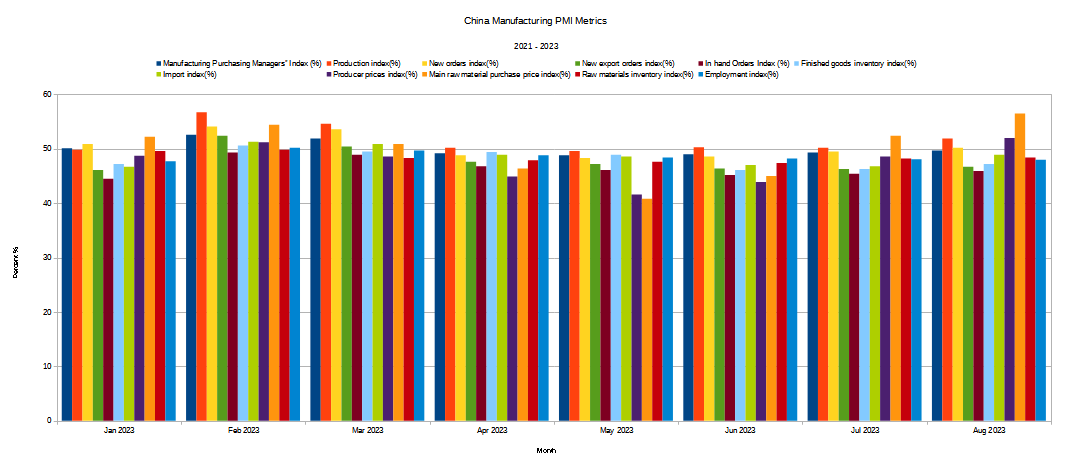

In fact, most of China’s Manufacturing PMI Metrics are printing contraction, and have been for months.

That’s an across the board slump and touches far more than just real estate or any other single economic sector. This is contraction across the span of the economy.

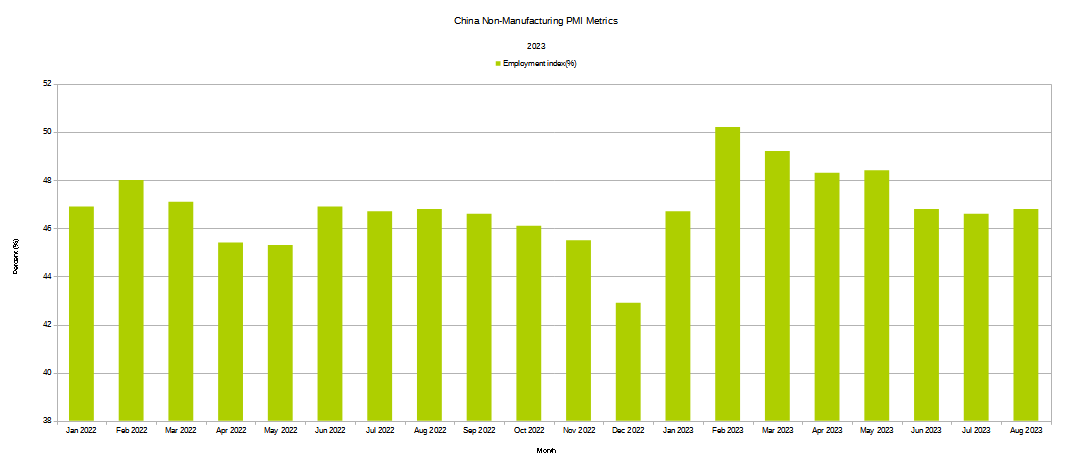

Even China’s Services PMI metrics are showing signs of weakness.

One metric stands out as particularly grim over the past two years: Employment. China’s service sector businesses have done an horrible job of hiring and retaining people.

Small wonder China’s youth unemployment has been so bad Beijing no longer releases unemployment data by age. Quite literally almost no one is hiring!

Nor is the service side of China’s economy poised to improve any time soon. Not with new service orders and new export orders having been stuck in contraction for most of 2022 and 2023.

With both services and manufacturing showing contraction, there can be little doubt as to why China’s inflation rate has printed negative recently. Quite literally everything is stuck in the doldrums.

While there are some bright spots of growth, such as China’s travel sector, they are too narrow and too small to provide enough of a lift to turn China’s economy around. As I have already examined, China’s travel sector is certainly not about to contribute towards rising oil prices, at least not to the degree the oil bulls are forecasting.

(Article is paywalled until September 15)

Aside from those small bits of economic progress, China’s economy as a whole is signalling deflation, stagnation, and Japanification. Most significantly, these are not new trends. Even when Evergrande first tumbled into debt default in 2021, it was clear that China’s economy was on the ropes.

At present, cataclysmic collapse is not on deck for the Middle Kingdom. While the real estate sector is collapsing in the wake of the Evergrande default, the economy as a whole has not yet gone into complete meltdown. While such is not an impossible outcome, the length of these deflationary trends alone suggests the more likely outcome for China is a Japan-style debt-deflationary cycle, with continued low consumption and minimal or no economic growth.

What is perhaps worse for China, however, is that China is either unable or unwilling to attempt the economic extreme medicine of massive monetary and fiscal stimulus theoretically necessary to reinflate the economy. Xi Jinping does not appear to be interest in attempting an “Abenomics” sort of solution. Yet without some form of government stimulus, China’s highly centralized and state-controlled economy does not get the levels of local demand necessary to inject fresh vigor into things.

Yet the government stimulus measures that have been implemented have been at most marginal efforts to stimulate around the edges. Some measures are of questionable stimulative effect at all, such as the decision to lower interest rates on existing mortgages.

Five of China's major state banks said on Thursday they will start to lower interest rates on existing mortgages for first-home loans, part of a series of support measures announced by Beijing in recent weeks.

Chinese regulators announced the policy last week to help homebuyers amid growing concern over the health of the world's second-largest economy and a series of crises in the nation's property sector.

While lowering interest rates on new mortages could help stimulate the property sector by making new mortgage loans cheaper, reducing interest rates in existing mortgages provides little in the way of stimulus, particularly for low loan demand. Making existing mortgages a bit cheaper does nothing to incent Chinese consumers to purchase additional homes and take out additional mortgages. Such measures are likely to put a marginal amount of additional disposable income in homeowner wallets, but that seems hardly sufficient to stimulate consumption within the Chinese economy. It is quite possible that any marginal disposable income so generated a fair number of Chinese homeowners would opt to use for paying down household debt, which would throw China into a “balance sheet recession” not unlike Japan’s experience in the mid- to late-90s.

In the aftermath of the 2007-2009 Great Financial Crisis, the world looked to China to lift the world economy up out the doldrums and put it back on the path of growth. That will not happen this time. China will not be riding to the world economy’s rescue. Indeed, if China’s economy deteriorates much further, China may be looking to the world for rescue.

It looks like China needs a good war. Taiwan should get ready.

China has painted themselves into a corner now.