The oil price cap is undeniably impacting Russia’s oil revenues, of that there can be no doubt. How else to interpret Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak’s call to reduce the deep discounts currently in effect on Russia’s benchmark Urals crude?

The discount on Russian oil has recently grown, but given the stabilization of the situation, it should be reduced, said Deputy Prime Minister, ex-head of the Ministry of Energy Alexander Novak.

“Now we are seeing that the discount against our oil has slightly increased. Naturally, because buyers are laying down risks, but given the stabilization of the situation, we think that this discount should decrease,” he told reporters.

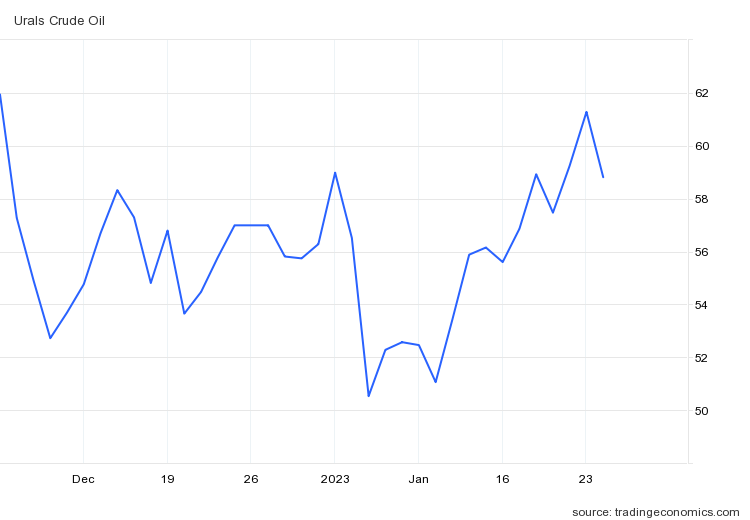

While trading and closing prices do vary, using the spot prices at Trading Economics as a guide, the discount between Brent and Urals crude has indeed grown significantly since the oil price cap was imposed—and was already significant even before the price cap.

On January 3, 2022, Urals crude traded at a $1.96/Bbl discount to Brent Crude (Brent == $78.57/Bbl, Urals == $76.61/Bbl).

On March 8, 2022, when Brent peaked at $123.48/Bbl, Urals Crude traded at $111.01/Bbl, for a discount of $12.47/Bbl.

On November 30, just before the price cap went into effect on December 5, Brent was trading at $86.99/Bbl, and the discount on Urals crude was $20.45/Bbl, for a Urals price of $66.54/Bbl.

Since the price cap has been imposed, that discount had grown by more than $8/Bbl. The January 19 Brent closing price was $86.16/Bbl and the Urals closing price was $57.47/Bbl, for a discount of $28.69/Bbl.

By January 24, with Brent closing at $81.13/Bbl and Urals closing at $58.81/Bbl, the discount had narrowed by $1.37//Bbl to $27.32/Bbl—still an increase of over $6/Bbl from November 30 levels.

As a means of limiting Russian oil revenues, the price cap has been quite impactful, regardless of how much or how little it actually influences Putin’s war policy towards Ukraine.

It should be noted, however, that since January 10, the spot price of Urals crude has been steadily rising, and on January 23 actually closed above the price cap, at $61.28/Bbl.

While the spot price quickly retreated, it is now conclusively demonstrated that the price cap can be breached—and probably will if the discount to Brent continues to narrow.

The functional purpose of the price cap is an unusual one insofar as sanctions are concerned. Because western nations want to keep Russian oil on the market, the goal is to limit Russia’s oil revenues and profits without necessarily limiting Russia’s oil shipments, thus hurting the Kremlin economically without triggering a worldwide shortage of oil.

Unlike a standard price cap, which typically bans the trade of a good and imposes costs on both the sanctioned and the sanctioning countries, the G7 price cap limits the price received by a single supplier – Russia – and only if the transaction uses particular services. According to the brief’s authors, this will reduce Russia’s foreign exchange revenues and reduce its capacity to wage war in Ukraine, while also making it possible for Russian oil to stay on the world market in the face of the impending complete European Union embargo and services ban.

As the above discounts show, the price cap has taken a significant bite out of Russia’s oil revenues.

However, there are indications that suggest the long term effects of the price cap may be a permanent or near-permanent reduction in Russia’s oil capacity. While the goal of the cap is to keep Russian oil on the market, the consequence of the cap may very well be the exact opposite.

In the week ending January 20, seaborn exports of Russian crude dropped 22% from the previous week, according to Bloomberg data.

Aggregate volumes of Russian crude slumped by 820,000 barrels a day, or 22%, to 2.98 million in the week to Jan. 20, giving up most of the previous week’s gain. The biggest drops were in flows from the Pacific ports, with smaller declines in Arctic and Black Sea exports. Baltic shipments were stable.

A key point to note here is that the biggest volume drops were from Russia’s Pacific ports—which means the decline was in the pricier ESPO crude rather than the benchmark Urals crude, which closed up on January 20 at $75.25/Bbl.

Loss of ESPO export volumes means Russia is losing more money than it would on a similar loss of Urals export volumes—especially since the ESPO contract has so far succeeded in defying the price cap.

While breaching the price cap has already been briefly demonstrated, Russia may find that pushing the price above the cap over the long term may ultimately be thwarted by two of the principal buyers of Urals crude since the sanctions regimes were imposed: India and China.

Limiting the limit price of Russian oil by the West has led to the emergence of additional income from India and China, through which Europe now receives Russian raw materials, Alexander Potavin, an analyst at FG Finam, shared his assessment with RIA Novosti.

According to international analytical companies, Europe and Britain continue to buy Russian raw materials, but now they do it through intermediaries - China, India and other Asian countries. In particular, mixed oil products are sent to the West, which are produced at Chinese and Indian refineries and contain Russian oil.

Simply put, China and India are quite happy to buy Russian crude under the price cap, mix it with a token amount of other blends, and then resell it—including back to Europe—at market prices. The price cap is nothing less than a revenue opportunity for both countries—and at a time when China in particular needs all the economic good fortune it can get.

Even smaller energy players such as Singapore are getting in on the arbitrage action in Russian crude created by the price cap.

Moscow, of course, is not pleased with this state of affairs, and is seeking to apply regulatory pressures to prevent such sales under the cap.

As it became known to Kommersant, the government will soon adopt a resolution prohibiting Russian companies from including references to the oil price ceiling introduced by the West in export contracts. Exporters will be required to submit contracts for verification to the FCS, which will be able to block shipments in case of violations. At the same time, companies themselves must ensure that their counterparties do not use the ceiling when reselling oil. By April 1, the Ministry of Energy will start monitoring the export price of Russian oil based on data on the conditions of actual shipments, which market participants are required to provide.

With the obvious economic interest of Russia’s new primary oil customers in purchasing under the price cap in order to sell above it, one wonders how much success Russian regulations will have—especially since Russia’s only mechanism for pushing back on the cap is to throttle production (the very thing with which it is already having at least some challenges).

An oft-overlooked challenge for Russian oil even going back before Putin chose to invade Ukraine has been to increase and sustain production capacity. As early as January of 2022, over a month before the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War, oil analysts were speculating Russia might already be at or near its short-term production capacity, and is simply not able to expand it further.

Russia failed to boost oil output last month despite a generous ramp-up quota in its OPEC+ agreement, indicating the country has deployed all of its current available production capacity.

With OPEC+ meeting in two days to consider output policy in the face of the fast-spreading omicron variant, Russia’s lack of growth highlights the limits of the group’s attempt to boost supply if demand continues to recover. Saudi Arabia, Iraq and the UAE can raise output, but others such as Angola, Nigeria and Kuwait are struggling to meet their quotas.

Nor has there been much confidence in Russia’s ability to expand its production capacity. In December of 2021—a full two months before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine—analysts were skeptical of Deputy Prime Minister Novak’s stated intent that Russia would get back to pre-pandemic production levels by May of 2022.

Russia is unlikely to hit its May target of pre-pandemic oil output levels due to a lack of spare production capacity but could do so later in the year, analysts and company sources said on Tuesday.

Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, in charge of Moscow's ties with the OPEC+ group of oil producers, has said output by May is expected to hit pre-pandemic levels, or about 11.33 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil and gas condensate, as seen in April 2020 .

However, many oil producers have reported they are almost out of spare production capacity having reduced output in tandem with other OPEC+ producers.

Based on the International Energy Agency’s Oil Market Report, Russia’s oil production has already fallen significantly since the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War last February.

One challenge Russia was facing even before the war as an aging oil production infrastructure and the need for new investment just to sustain production. Aging infrastructure was a stated reason why oil analysts in December of 2021 did not expect Novak’s capacity ramp-up projections to pan out.

Part of the problem is old wells, mostly in Siberia, that are struggling to increase output, industry sources say.

As a consequence, Russia was forced to acknowledge last October that it failed to ramp up production as projected.

The Russian Federation failed in October to increase oil production, which so far remains at a level of no more than 1.47 million tons per day, taking into account the production of condensate, sources familiar with the situation told Kommersant. The export of Russian oil by sea and oil pipelines decreased by almost 2% compared to September, to about 640 thousand tons per day.

One hope for Russia to boost production is getting its Sakhalin-1 project fully back online after it was shuttered following ExxonMobil’s withdrawal from the project.

According to Kommersant's interlocutors, in November the situation could be improved by resuming production at the Sakhalin-1 project, which stopped in May as a result of ExxonMobil's refusal to ship shipments (see Kommersant on October 17). In October, the Russian authorities changed the Sakhalin-1 operator to Rosneft, and Exxon withdrew from the project. It was assumed that this year Sakhalin-1 will produce over 24 thousand tons per day. After its restart, it is still possible to enter production in the amount of less than half of the plan.

If Russia hopes to boost oil production significantly in the near term, getting Sakhalin-1 back to full production is likely essential—and that isn’t happening just yet.

One of Russia’s major hurdles to increasing production has been the loss of western oil drilling and exploration technology, both of which withdrew from Russia following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Russian Federation cannot increase production to the level recorded by OPEC+, for a number of reasons, the main of which relate to sales, such as the refusal of a number of partners from contracts due to fear of secondary sanctions, high discounts in available markets, problems with logistics, says Kasatkin Consulting partner Dmitry Kasatkin, the departure of technologies due to sanctions is also starting to affect, which is why the cost of production is growing. According to his estimates, in December, production may fall by 9%, to 1.3 million tons per day.

According to energy intelligence and analysis firm Rystad Energy, as a result of sanctions applied in response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Russia has lost as much as $15 billion in upstream investments in their oil and gas sectors.

The financial impact of Western sanctions and the widescale exodus of foreign partners from the Russian oil and gas sector are beginning to materialize, with upstream investments set to sink to $35 billion in 2022, according to Rystad Energy research. Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February this year, upstream investments in Russia were expected to approach $50 billion in 2022.

Investments in Russia’s upstream sector totaled $45 billion last year, rebounding from Covid-19-induced lows of $40 billion in 2020. But as Russia becomes increasingly shut off from the global energy market, investments have sunk well below levels seen in the pandemic-affected years of 2020 and 2021 and will remain subdued until at least 2025. The stagnation in investments will lead to a drop in project final investment decisions and force operators to make hard decisions on spending. While domestic giants Gazprom and Rosneft will be able to keep spending around 2021 levels, other players will see a significant drop in investments.

In particular, greenfield investments—development of new oil fields and new production facilities—are suffering, with there being a distinct possibility of no greenfield investment in oil and gas being moved forward in Russia during 2023.

Greenfield investments are set to suffer the largest drop in spending due to the sudden sharp decline in approval activity this year. Investments in new Russian projects are projected to fall 40% from last year, tumbling from $13.7 billion to just $8 billion this year. Only around 2 billion barrels of oil equivalent of resources were sanctioned last year, with almost all those volumes coming from the Baltic LNG project at which Gazprom started construction in May 2021. In light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, however, financing the project will be a struggle for Gazprom. Service companies have already started leaving Russia, while Linde, which is providing its proprietary LNG technology for the project, has also exited the country.

No significant new projects are expected to be sanctioned in Russia next year, but activity will resume in 2024 with the Gazprom-operated Chayandinskoye (Phase 2) gas-condensate field – a resource base for the Power of Siberia-1 gas pipeline to China – and the Payyakhskoye oilfield, part of Rosneft’s huge Vostok Oil project in the north of the country.

Without fresh infrastructure investment, Russia’s oil production capacities can only decline.

Even before aging infrastructure becomes a factor, however, the current sanctions regimes placed on Russia for its militarism are forecast to cause a significant drop in Russian oil exports in 2023.

The World Bank expects Russian oil exports to fall in 2023 due to additional European Union sanctions that began in December 2022 for crude oil and will begin in February 2023 for petroleum products.

However, the overall reduction in Russian exports is likely to be less than initially expected, as the G7 oil price cap will allow countries importing oil from Russia to continue to access EU and UK insurance facilities, provided they adhere to the price cap.

The EU’s coming embargo on refined oil products, set to take effect in February, may potentially be even more impactful.

In an attempt to punish Russia for the conflict in Ukraine, the European Union banned seaborne Russian crude imports from Dec. 5 and will ban Russian oil products from Feb. 5.

"The oil products' embargo will have a greater impact than the restrictions on crude oil," said the senior Russian source who spoke on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity the situation.

The source said the sanctions will lead to more crude oil supplies from Russia, which lacks storage capacity for oil products.

The overall impact to Russian production has been forecast at approximately 1 million bpd.

"We think that the refined product embargo may be more significant than the crude embargo, given that exporting a given amount of products is much more logistically complex than an equivalent amount of crude," said Ron Smith of Moscow-based brokerage BCS.

"Our assumption has been that the two embargoes combined would reduce Russian oil output and total exports by perhaps 1 million barrels per day by the end of (first quarter) 2023."

Faced with lack of capital investment, lack of significant profits due to the steep (and getting steeper) discount on Russian oil, and soon a lack of existing output, the question has to be asked: from where will Russia get the capital necessary to sustain its oil industry over the long haul? Where will the funds come for new exploration and development of new oil fields?

It is, of course, far too soon to write off the Russian oil industry from just the price cap and other EU/NATO sanctions. Russia continues to pump, pipe, and export oil, although not as much as it had been and likely to soon be even less. The price cap is not impervious, and as oil prices rise will likely come under increasing pressure (and will likely ultimately fail).

However, it is not too soon to note that, despite the best pitches by Alexander Novak, Russia’s Urals crude is trading at an even deeper discount than before the price cap. It is not too soon to note that Russia is demonstrably being denied oil revenue, even as it has to fund its very expensive war in Ukraine. It is not too soon to do the math and realize that if Russia cannot restore a fair amount of the oil profit it has lost as a result of choosing to invade Ukraine, declines in production now may prove less easily reversed later on, and could even prove permanent.

Given Russia’s capacity challenges before the sanctions, there is a distinct possibility the sanctions may have longer term consequences for Russian oil than has been contemplated by either side.