Did Volcker "Beat" Inflation Or Simply Ring-Fence It?

Re-Thinking Paul Volcker's True Impact On Inflation And The US Money Supply

One of the long-standing truisms of modern economics is Milton Friedman’s famous assertion that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”1.

Given the current state of the US money supply, and the recent return of significant consumer price inflation, reconciling Friedman’s view of inflation with the available data is increasingly a challenge—for the simple fact that correlating inflation to changes/increases in the supply of money in the US simply cannot be done based on the available data.

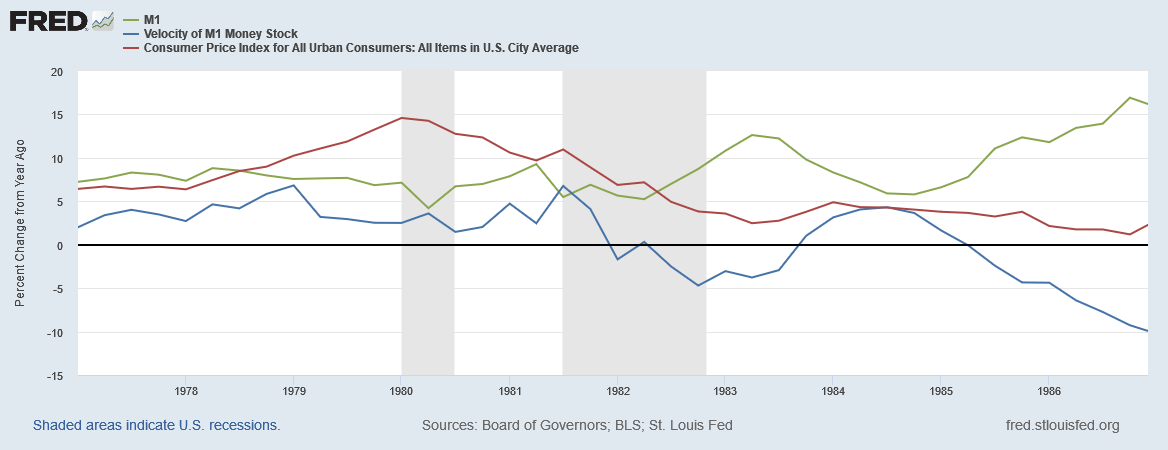

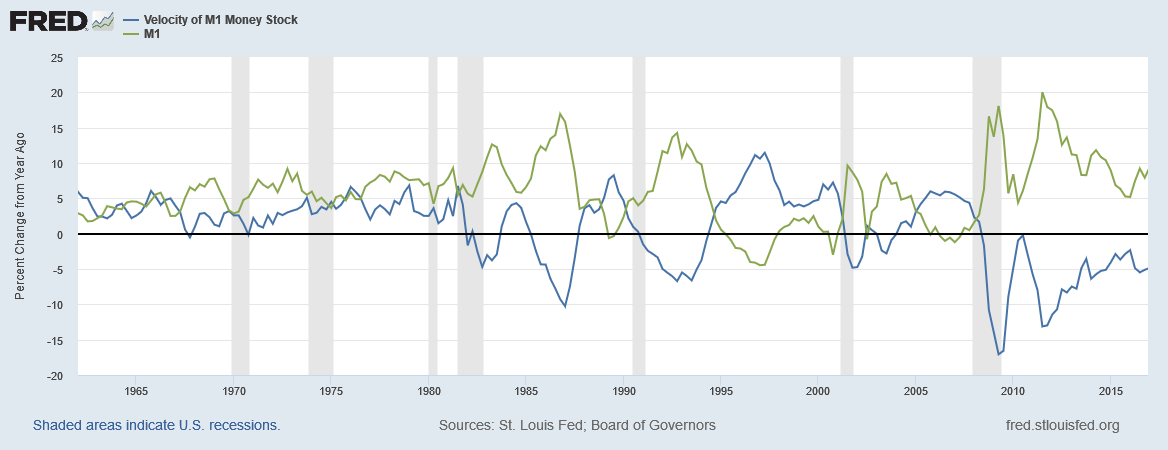

While during the 1960s there is broad correlation between the rise in the M1 money supply and an increase in consumer price inflation, that correlation began to break down in the 1970s, and after the Volcker Recession of the early 1980s it disappears altogether.

Although I am far from an economist of Milton Friedman’s caliber, the data as presented plainly shows that a simple association of money supply to inflation, while broadly valid over 50 years ago, ceased to be valid in the 50 years since. Increases in money supply are not matched with rises in consumer price inflation, and decreases in the money supply (or, rather, reductions in the rate of increase), are not met with corresponding fluctuations in consumer price inflation.

What changed? Was Friedman wrong? Or has some other dynamic altered the relationship between money and inflation?

In digesting much of the available data surrounding Federal Reserve monetary policies of the past few decades, I have come to the conclusion that, while Friedman’s truisim is broadly valid, one cannot apply it in a simple, linear fashion. Consequently, shifts in other money dynamics besides money supply have over time proven to be quite consequential to inflation in the US, in particular the velocity of the money supply.

Clarifying Friedman’s Thesis

It is important to be absolutely clear on what Milton Friedman meant by describing inflation as a purely monetary phenomenon, and also to address his understanding of the totality of factors that might influence money supplies to produce inflation.

First and foremost, we must remember that Friedman defined inflation as a broad macroeconomic trend2.

By inflation, I shall mean a steady and sustained rise in prices.

Applying Friedman’s definition, we are perhaps being too particular when we scrutinize the Consumer Price Index for every price shift up or down. Inflation is not merely an increase in prices, but a pattern of increase. Month-to-Month comparisons and even Year-on-Year comparisons, which are intrinsically focused on individual data points, can be somewhat misleading without a context of prior months and prior years.

Additionally, we should recognize also that Friedman also allowed for monetary velocity to play a role in producing an inflationary (or disinflationary) trend3.

In other words, movements in the velocity of money circulation exaggerated the effect of the behaviour of the stock of money itself.

This seems almost common-sensical, and goes straight to the fundamental equation of the quantity theory of money4:

Following the dynamics of this equation, if the stock of money rises while the quantity of goods/services purchased (effectively, the physical output of a nation’s GDP) remains the same, prices mathematically must rise to match. Similarly, if the stock of money remains constant but the velocity of that money rises, prices must also rise to match. It is that rise in prices which Milton Friedman counted as inflation, where it occurred over a period of time.

As a consequence of this equation however, should the stock of money and the velocity of money move in opposite directions but in equal proportions (e.g, money supply doubles while velocity halves), the impact of both changes are offsetting and inflation is nil. Remember that point—it will become crucial later.

The 1970s—A Decade Of Change

Returning to the graph above, beginning in about 1971 we begin to see a departure from the broad correlation between money supply and inflation. In particular, in 1971 we see a brief disinflationary episode coupled with a rise in the money supply—the exact opposite of what we should see.

However, during this period—actually beginning in the late 1960s, we see a significant divergence between shifts in money supply and shifts in money velocity.

This was also a period when the Federal Reserve, along with several of the other major central banks in the world, were struggling to sustain the dollar gold peg that was the underpinning of the Bretton Woods system. In particular, the Federal Reserve began relying on currency transactions as a substitute for gold redemption5.

From 1962 until the closing of the U.S. gold window in August 1971, the Federal Reserve relied on “currency swaps” as its key mechanism for temporarily defending the U.S. gold stock. The Federal Reserve structured the reciprocal currency arrangements, or swap lines, by providing foreign central banks cover for unwanted dollar reserves, limiting the conversion of dollars to gold.

In March 1962, the Federal Reserve established its first swap line with the Bank of France and by the end of that year lines had been set up with nine central banks (Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Canada). Altogether, the lines provided up to $900 million equivalent in foreign exchange. What started as a small, short-term credit facility grew to be a large, intermediate-term facility until the U.S. gold window closed in August 1971. The growth and need for the swap lines signaled that they were not just a temporary fix, but a sign of a fundamental problem in the monetary system.

Even before Nixon closed the gold window in 1971, the linkage between gold and the dollar was already being deliberately undermined.

At the same time, change in monetary velocity, which in the 1960s had been tracking fairly closely to changes in the money supply, diverged, with money velocity rising far more slowly than money supply. During this period, we see the expected rise in consumer price inflation (see first chart above), but of a much lower magnitude than the rise in money supply alone might suggest.

This is actually in keeping with Friedman’s assessment of the role of money velocity as altering the impact of money supply growth on inflation. The slower money velocity of that time period appears to have acted as a moderator on inflation.

The challenge for the Federal Reserve was that, within the Bretton Woods system, the currency swap lines were unsustainable as either a dollar or gold defense. As a result, the economic brain trust of the Nixon Administration, which included Paul Volcker, who before he became Fed Chairman was an influential undersecretary of the Treasury, opted to abandon the gold standard and close the gold window in August of 19716.

With inflation on the rise and a gold run looming, Nixon’s administration coordinated a plan for bold action. From August 13 to 15, 1971, Nixon and fifteen advisers, including Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns, Treasury Secretary John Connally, and Undersecretary for International Monetary Affairs Paul Volcker (later Federal Reserve Chairman) met at the presidential retreat at Camp David and created a new economic plan. On the evening of August 15, 1971, Nixon addressed the nation on a new economic policy that not only was intended to correct the balance of payments but also stave off inflation and lower the unemployment rate.

Paul Volcker, the man who would take on inflation in historic fashion not even a decade later, was a principal voice in persuading Nixon to abandon the gold standard in 1971—something he had long labored while at the Treasury Department to achieve7.

More than two years before Nixon slammed down the “gold window,” Volcker, the recently appointed undersecretary of the treasury for monetary affairs, gave an oral presentation to Nixon and his closest advisors on US balance-of-payments problems. The presentation was based on a memo that the secret “Volcker group,” initiated by Henry Kissinger, spent five months preparing.

Nixon closed the gold window in August of 1971, and by 1973, what few remnants of Bretton Woods that were still in effect melted away, and the era of floating exchange rates came into being.

The changes Volcker facilitated in 1971 did not halt inflation in the US—and so in 1979, when Paul Volcker became Federal Reserve Chairman, he did so with a mandate to rein in inflation. His solution: rein in the money suppy to force inflation down8.

“By emphasizing the supply of reserves and constraining the growth of the money supply through the reserve mechanism, we think we can get firmer control over the growth in money supply in a shorter period of time,” Volcker told the assembled reporters. “But the other side of the coin is in supplying the reserve in that manner, the daily rate in the market…is apt to fluctuate over a wider range than had been the practice in recent years” (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 1979a).

As a result of the new focus and the restrictive targets set for the money supply, the federal funds rate reached a record high of 20 percent in late 1980. Inflation peaked at 11.6 percent in March of the same year. Meanwhile, the new policy was also pushing the economy into a severe recession where, amid high interest rates, the jobless rate continued to rise and businesses experienced liquidity problems. Volcker had warned that such an outcome was possible soon after the October 6, 1979, FOMC meeting, telling an ABC News program that “some difficult adjustments may lie ahead,” (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 1979b). With the economy now facing a recession, it is perhaps not surprising that the Fed came under widespread public criticism.

Interestingly enough, however, although Volcker spoke of reining in the money supply, M1 money supply growth continued throughout his battle with inflation. More crucial is the fact that while money supply growth continued, money velocity dipped at first, and then began a general downward trend that lasted for most of Volcker’s tenure as Fed Chair.

The Data Does Not Match The Myth

While the Volcker myth focuses on his aggressive interest rate hikes as the principal weapon deployed against inflation, there is another perhaps more important impact of his policies: beginning in the early 1980s, a startling symmetry arose between money supply changes and money velocity changes.

Prior to 1979, while money supply and money velocity can and often did diverge, their fluctuations appear to have been largely independent of each other. After 1980, we see a pattern whereby a rise in the pace of money supply growth is matched by a drop in the pace of money velocity, and vice versa.

We now return to the point I highlighted earlier:

Should the stock of money and the velocity of money move in opposite directions but in equal proportions (e.g, money supply doubles while velocity halves), the impact of both changes are offsetting and inflation is nil.

Whether by accident or design, what Volcker achieved in 1980 was a pattern of money growth and money velocity that in large measure produced exactly this effect: money supply growth (or shrinkage) was always more or less offset by money velocity deceleration or acceleration.

The impact of this phenomenon on consumer price inflation is immediately apparent.

It is this phenomenon, and not interest rate policies, which have been most impactful on inflation. In fact, when we set the Consumer Price Index and various US Treasury interest rates to a common baseline index, we see that the general downward trend in interest rates since the 1980s has had little or no impact to the trend in the CPI.

Moreover, this symmetry between money supply and money velocity even extended to Powell’s ginormous expansion of the M1 money supply in 2020.

Too Much Room To Maneuver

Powell’s expansion of the M1 money supply, from a monetary perspective, may very well have been the crucial misstep which opened the door for inflation to return. While this symmetric effect had largely ring-fenced inflation, such that it could never rise much above 2-3%, the 2020 money supply expansion was over three hundred percent, and even after the large expansion was completed throughout 2020 the pace of money supply growth was considerably larger than in the past—as late as the first quarter of 2022 the year on year money supply growth was still in excess of 11%. Consumer price inflation suddenly had much more room to grow, which it did.

Even though money supply growth soon after returned to its historical range below 7%, inflation had already jumped above 8%. While the proximate causes of inflation’s rise were almost entirely the exogenous supply shocks introduced as a result of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdowns, the expansion of the money supply expanded the range within which those supply shocks could plausibly push prices up. The monetary aspect of the current inflation arguably has been that the the range for potential inflationary effects was increased, with the wanton destruction of global supply chains during the lunatic lockdowns providing an ample supply of exogenous inflationary effects to fuel the increase.

Will The Status Quo Ante Return?

Recent summary reports of the Consumer Price Index suggest that consumer price inflation may have peaked. Absent any further supply shocks, there is at least some hope that inflation will return to its previous confines—provided the symmetric effect between money supply and money velocity still holds. With money velocity already close to effective zero, it is an open question whether the symmetric effect, which has been sustained uninterrupted since 1980, will continue.

If that effect breaks down, the “ring fence” effect thus imposed on consumer price inflation in all probability disappears. Even if the effect does not break down, there is at present no assurance that consumer price inflation will oblige and return to its previous confines.

The assurance we do have, from all the foregoing data, is that, as I have stated multiple times before, Jay Powell’s interest rate hikes will have no direct impact on inflation. To the extent that they may reinforce the symmetric effect, there is the possibility that, as recession takes hold, inflation will once again move within its bounds and the status quo ante on inflation be restored.

However, restoring that status quo will come at the price of a long and deep recession, perhaps even a depression. Worse still, the jobs destruction and demand destruction sought by the Fed will inhibit the regeneration of various supply chains, which is a necessary predicate towards any degree of permanent economic recovery.

Powell is heading down this wrong path because the Volcker myth is fundamentally wrong: Paul Volcker did not “beat” inflation with interest rates. He merely ring-fenced it, keeping it corraled but never ever fully tamed.

Friedman, M. “First Lecture.” Inflation: Causes and Consequences, Asia Publishing House, 1963. Available Online At https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/271018/full

ibid.

ibid.

Barone, A. What Is the Quantity Theory of Money: Definition and Formula. 17 May 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/insights/what-is-the-quantity-theory-of-money/.

Ghizoni, S. K. Nixon Ends Convertibility of U.S. Dollars to Gold and Announces Wage/Price Controls. 22 Nov. 2013, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/gold-convertibility-ends.

ibid.

Salerno, J. T. Paul Volcker: The Man Who Vanquished Gold. 19 Dec. 2019, https://mises.org/wire/paul-volcker-man-who-vanquished-gold.

Medley, B. Volcker’s Announcement of Anti-Inflation Measures. 22 Nov. 2013, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/anti-inflation-measures.

How does one measure Velocity?