Powell's Puzzle: Rate Hikes Still Are Not Having Much Effect On Inflation

How Much Longer Can He Pretend That Recession Is Unnecessary To Bring Down Inflation?

Yesterday’s Producer Price Index summary from the BLS was not good news. Despite six months and counting of interest rate hikes from the Fed, producer price inflation—widely seen as a predictor of future consumer price inflation—rose month on month, and only slightly inched down year on year.

The Producer Price Index for final demand increased 0.4 percent in September, seasonally adjusted, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Final demand prices declined 0.2 percent in August and 0.4 percent in July. (See table A.) On an unadjusted basis, the index for final demand advanced 8.5 percent for the 12 months ended in September.

Rising inflation is not supposed to be happening now. Rising interest rates are supposed to bring about disinflation1—a decline in the rate of inflation—and even deflation for some goods and services. Powell’s iteration of the Volcker playbook is not working.

This Isn’t Supposed To Be Happening….Is It?

The theory says that the Fed raises rates to fight inflation and cuts rates to cause inflation2.

When the Federal Reserve responds to elevated inflation risks by raising its benchmark federal funds rate it effectively increases the level of risk-free reserves in the financial system, limiting the money supply available for purchases of riskier assets.

Conversely, when a central bank reduces its target interest rate it effectively increases the money supply available to purchase risk assets.

The premise is simple: make money more expensive and people are less likely to use it—which is to say spend it.

By increasing borrowing costs, rising interest rates discourage consumer and business spending, especially on commonly financed big-ticket items like housing and capital equipment. Rising interest rates also tend to weigh on asset prices, reversing the wealth effect for individuals and making banks more cautious in lending decisions.

That is the theory. Unfortunately the reality is somewhat different—and even the Federal Reserve admits this.

In an address while still a Federal Reserve Governor, former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke acknowledged the perception that a tweak in interest rates corrects inflation3.

Superficially, the FOMC decision process may appear straightforward. A commonly used analogy takes the U.S. economy to be an automobile, the FOMC to be the driver, and monetary policy actions to be taps on the accelerator or brake. According to this analogy, when the economy is running too slowly (say, unemployment is high and growth is below its potential rate), the FOMC increases pressure on the accelerator by lowering its target for the federal funds rate, thereby stimulating aggregate spending and economic activity. When the economy is running too quickly (say, inflation appears likely to rise), the FOMC switches to the brake by raising its funds rate target, thereby depressing spending and cooling the economy. What could be simpler than that?

What gets glossed over by economy pundits since is that Bernanke went on to demolish the perception, and even called into quesiton the efficacy of interest rate hikes in taming inflation overall4 (emphasis mine).

First, policymakers working to keep the economy from going off the road must deal with informational constraints that are far more severe than those faced by real-world drivers. Despite the best efforts of the statistical agencies and other data collectors, economic data provide incomplete coverage of economic activity, are subject to substantial sampling error, and become available only with a lag. Determining even the economy's current "speed," consequently, is not easy, as can be seen by the fact that economists' estimates of the nation's gross domestic product (GDP) for the current quarter may vary widely. Forecasting the economy's performance a few quarters ahead is even more difficult, reflecting not only problems of economic measurement and the effects of unanticipated shocks but also the complex and constantly changing nature of the economy itself. Policymakers are unable to predict with great confidence even how (or how quickly) their own actions are likely to affect the economy. In short, if making monetary policy is like driving a car, then the car is one that has an unreliable speedometer, a foggy windshield, and a tendency to respond unpredictably and with a delay to the accelerator or the brake.

Does “respond unpredictably” sound like “interest rate hikes work to combat inflation”? Not hardly. If anything this is an admission by Bernanke that monetary policy is never more than a “best guess”, and perhaps not even that.

Bernanke went on to articulate a far different view of interest rates and monetary policy overall.

The current funds rate imperfectly measures policy stimulus because the most important economic decisions, such as a family's decision to buy a new home or a firm's decision to acquire new capital goods, depend much more on longer-term interest rates, such as mortgage rates and corporate bond rates, than on the federal funds rate. Long-term rates, in turn, depend primarily not on the current funds rate but on how financial market participants expect the funds rate and other short-term rates to evolve over time. For example, if financial market participants anticipate that future short-term rates will be relatively high, they will usually bid up long-term yields as well; if long-term yields did not rise, then investors would expect to earn a higher return by rolling over short-term investments and consequently would decline to hold the existing supply of long-term bonds. Likewise, if market participants expect future short-term rates to be low, then long-term yields will also tend to be low, all else being equal. Monetary policy makers can affect private-sector expectations through their actions and statements, but the need to think about such things significantly complicates the policymakers' task (Bernanke, 2004). In short, if the economy is like a car, then it is a car whose speed at a particular moment depends not on the pressure on the accelerator at that moment but rather on the expected average pressure on the accelerator over the rest of the trip--not a vehicle for inexperienced drivers, I should think.

The reality of monetary policy, according to Bernanke in 2004, is that it relies almost entirely on the Federal Reserve’s ability to manage expectations.

This is a far different view of the Fed’s use of interest rates than what was articulated by Jay Powell at Jackson Hole back in August5.

July's increase in the target range was the second 75 basis point increase in as many meetings, and I said then that another unusually large increase could be appropriate at our next meeting. We are now about halfway through the intermeeting period. Our decision at the September meeting will depend on the totality of the incoming data and the evolving outlook. At some point, as the stance of monetary policy tightens further, it likely will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases.

Rather than managing expectations, Powell proposed monetary policy is and should be driven entirely by the totality of economic data available at the moment of decision-making, with some cursory attention paid to future trends and dynamics. Alas for poor Powell, the September Producer Price Index summary shows how ineffective such a deployment of Fed monetary policy and interest rates in particular.

Producer Price Inflation Bodes Ill For Consumer Price Inflation

As I have noted multiple times in the past, while Powell claims to be focused on the “totality of the incoming data”, that same data shows how utterly ineffective the Powell policy of repeated rate hikes has been.

The September Producer Price data not only demonstrates Powell’s impotency yet again, over producer price inflation, but it also stands as a pessimistic predictor of where consumer price inflation will head next. As producer prices are a leading indicator of what’s in store for consumer prices, we can look forward to consumer price inflation at best showing a marginal decrease year on year, and potentially increasing month on month in the same fashion as producer price inflation. This would be completely in keeping with the observed behaviors of both metrics.

While producer price inflation has greatly outpaced consumer price inflation since mid-2021, an historical anomaly in both the magnitude and duration of the deviation, the recent declines in the PPI have largely closed the gap, to where once again the PPI and the CPI largely hew to the same inflationary rises and falls.

Thus, the best hope for today’s upcoming Consumer Price Index Summary will be little to no change in inflation. There might be some decline, but the odds of consumer price inflation for September falling below 8% is slim.

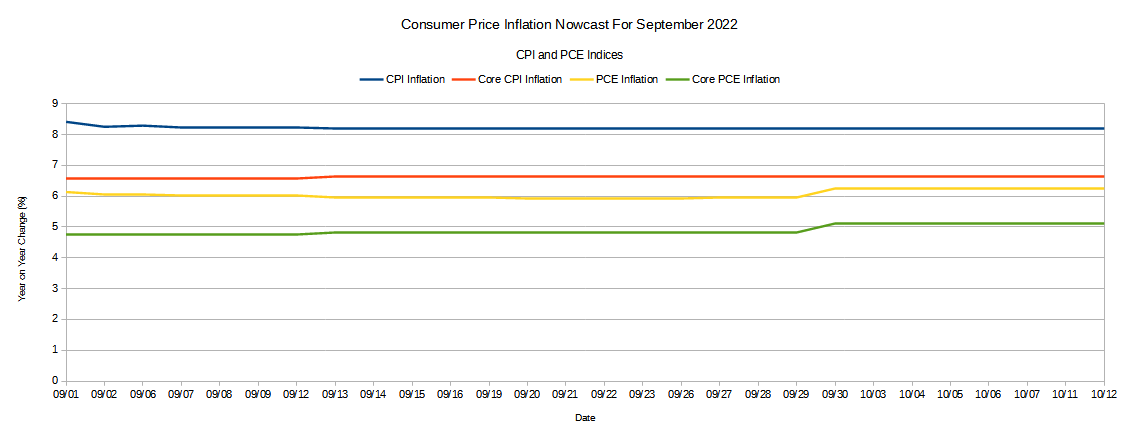

Certainly the Cleveland Fed’s inflation nowcast does not show any great decrease in consumer price inflation for September.

Still No Sign Interest Rates Are Moderating Inflation

What the Producer Price Index shows yet again—and what the Consumer Price Index is likely to show yet again—is that Powell, by turning to interest rate hikes again and again and again to tame inflation and generate some better inflation data is still foolishly trying to ice skate up hill. Even a brief view of inflation vs the yield on 10 Year Treasuries shows that inflation has largely ignored Powell’s efforts to boost interest rates.

Bernanke’s admission that interest rates are an unpredictable and unreliable weapon against inflation appears to be more in line with the observed realities than Powell’s insistence that he can crush inflation with interest rates, in effect repeating the Volcker Recession “solution” to inflation.

What neither the financial media nor Jay Powell are willing to admit is that the Volcker playbook corrals inflation because a recession is triggered and amplified. It is the recession that tames the inflation beast, not the interest rate hikes. Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin said that quiet part out loud earlier this year.

However, further on down, Barkin said the quiet part out loud about what “whatever it takes” really means (emphasis mine).

Barring an unanticipated event, I see rising rates stabilizing any drift in inflation expectations and in so doing, increasing real interest rates and quieting demand. Companies will slow down their hiring. Revenge spending will settle. Savings will be held a little tighter. At the same time, supply chains will ease; you have to believe chips will get back into cars at some point. That means inflation should come down over time — but it will take time.

Let that bit sink in. The reason rate hikes “work” to cure inflation is that rising interest rates make the cost of credit (aka, the “cost” of money) too high for consumers to utilize. Consumers are forced to spend less. Along the way, a few jobs are wiped out, a few workers are laid off, and eventually prices come down.

Recession, not disinflation, is the Fed’s ultimate endgame with rate hikes. That is what it has always been.

The only real question is how long will Jay Powell pretend otherwise?

Folger, J. Inflation & Interest Rates Relationship Explained. 5 May 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/12/inflation-interest-rate-relationship.asp.

ibid

Bernanke, B. S. FRB: Speech, Bernanke “The Logic of Monetary Policy” December 2, 2004. 2 Dec. 2004, https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2004/20041202/default.htm.

ibid

Powell, J. H. Speech by Chair Powell on Monetary Policy and Price Stability. 26 Aug. 2022, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20220826a.htm.

"Powell’s iteration of the Volcker playbook is not working."

Do you remember how many years of rising rates it took in the late 1970s and how high those rates had to get before inflation came down?

I do. :)