Does Anyone Have The Truth About Trump's Tariffs?

Nope. All Anyone Has Is Propaganda And Speculation

Depending on which media outlet you choose for your news, and depending on what day of the week it is, President Trump’s proposed tariff strategy is either an economic apocalypse that will impoverish the American consumer, or an economic masterstroke that will restore American economic vitality.

The proponents for both sides are constantly bringing out their “experts” to argue their side, and to tell in obsessive detail how wrong the other side is. That arrogant certainty of their own position is the one thing both sides have in common.

Which argument is correct? Are Trump’s tariffs a hidden tax to eat away at already constrained American wallets? Are they a necessary part of a healthy economic policy?

Despite the bloviations of the “experts”, the answer is “Yes, but perhaps no. It really depends.” In other words, all the “experts” are simply guessing and pretending they really do have an economic crystal ball.

Nonsense.

First, let’s be clear on what a tariff is, and how it gets deployed in the modern economy.

The most fundamental principle to understand about a tariff is that it is a form of trade barrier between nations1.

Tariffs are a type of trade barrier imposed by countries in order to raise the relative price of imported products compared to domestic ones. Tariffs typically come in the form of taxes or duties levied on importers and eventually passed on to end consumers. They're commonly used in international trade as a protectionist measure, with the aim of advantaging domestic producers and raising revenue.

The basic idea behind a tariff is to make an imported good more expensive than either a domestic alternative, or perhaps even another imported item from a different country.

The mechanism of most tariffs is a simple one: the tariff—sometimes called an import duty—is collected at the port of entry. In the United States, this is one of the many responsibilities of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Why do countries levy tariffs? There are several reasons for tariff policies, all of which involve protecting some aspect of the domestic economy.

A major argument that has often been used to justify tariffs in the past is that other countries, particularly those in the developing world, have structurally cheaper labor costs (frequently owing to a lack of labor or other regulation) and so domestic firms operate at a permanent disadvantage to foreign manufacturers.

The unemployment argument often shifts to domestic industries complaining about cheap foreign labor, and how poor working conditions and lack of regulation allow foreign companies to produce goods more cheaply. In economics, however, countries will continue to produce goods until they no longer have a comparative advantage (not to be confused with an absolute advantage).

By assessing an import duty, or tariff, on goods coming in from such a country, that permanent disadvantage of the domestic manufacturer in theory is mitigated, making the domestic produce more competitive with the imported goods.

Another reason typical among developed nations is as a retaliation against a country which has presumably violated various trading rules or regulation.

Countries may also set tariffs as a retaliation technique if they think that a trading partner has not played by the rules. For example, if France believes that the United States has allowed its wine producers to call its domestically produced sparkling wines "Champagne" (a name specific to the Champagne region of France) for too long, it may levy a tariff on imported meat from the United States.

A good example of how retaliatory tariffs work is the initial tariffs against solar cell systems and washing machines levied against Chinese firms by President Trump during his first term of office2.

USTR made the recommendations to the President based on consultations with the interagency Trade Policy Committee (TPC) in response to findings by the independent, bipartisan U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) that increased foreign imports of washers and solar cells and modules are a substantial cause of serious injury to domestic manufacturers.

The essential finding was that Chinese firms were “dumping”3—selling items in a foreign market at an artificially low cost, frequently with the specific intent of capturing a share of that foreign market by driving out domestic sellers.

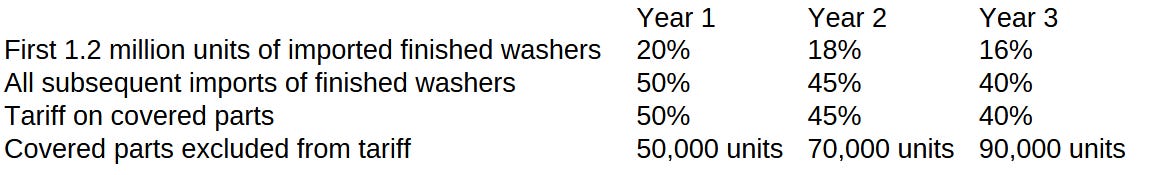

The tariffs imposed additional import fees on Chinese washing machines on a progressive scale.

For imports of large residential washers, the President approved applying a safeguard tariff-rate quota for three years with the following terms:

While the initial impact of the tariff was punitive and was intended to increase the price of Chinese washing machines and solar cells, the stated aim was to establish a trading relationship that was mutually beneficial and which did not involve Chinese firms “dumping” goods on the US market. At the time the tariffs were announced, particular mention was made of an improved trading relationship regarding solar cells.

The U.S. Trade Representative will engage in discussions among interested parties that could lead to positive resolution of the separate antidumping and countervailing duty measures currently imposed on Chinese solar products and U.S. polysilicon. The goal of those discussions must be fair and sustainable trade throughout the whole solar energy value chain, which would benefit U.S. producers, workers, and consumers.

Donald Trump would enact several more tariffs on China, as well as on other countries, with economists still arguing over whether his trade policies were a success or a failure.4

Now that President Trump has won re-election, many pundits are predicting that his promise to wield the tariff weapon aggressively to rebalance US trade relationships in favor of American producers and American workers will end up costing Americans, possibly bigly.

Economists widely forecast that tariffs of this magnitude would increase prices paid by U.S. shoppers, since importers typically pass along a share of the cost of those higher taxes to consumers.

Trump's tariffs would cost the average U.S. household about $2,600 per year, according to an estimate from the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

The argument against such tariffs is that they are little more than a hidden tax which is ultimately paid by the American consumer.

But here’s the downside of tariffs: They almost always, at least in the immediate future until markets can adjust, make goods more expensive for the American consumer. Tariffs are not, in fact, paid for by foreign countries. It is the importers, aka the American companies, that pay tariffs. And those companies, universally, end up passing that “tax” onto the consumer in the form of higher prices.

Other arguments against tariffs involve their capacity to increase costs even to domestic manufacturers.

But tariffs also have downsides, and those can outweigh the economic benefits. Companies charge Americans more to pay for them. And they are regressive, meaning they place a higher burden on poor families than on rich ones.

Tariffs can also backfire by hurting U.S. manufacturers. American factories use a lot of foreign parts and materials, and tariffs make it more expensive to get these. Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs, for instance, got U.S. firms to make more metals — but because the price rose, other companies that use metals to make things, like industrial machinery and auto parts, ended up manufacturing less.

To add insult to injury, according the the “experts”, such tariff trade war logic invariably backfires.

Now that we know who will pay for any new tariffs, let us examine Trump’s goals. To deter war, Trump says he will threaten to impose tariffs of 100% on countries who attack or threaten us or our allies. The unstated assumption is that a 100% tariff would hurt the offending country’s economy by reducing its exports to America, and that this economic harm would deter any aggression.

For this to work, our imports of that country’s products would have to fall dramatically or that country would have to absorb most of the tariff by lowering the prices of its exports so they remain competitive with similar products. The latter is unlikely since the research shows most of the time countries pass on the higher prices to U.S. consumers. This means the economic harm to the other country would have to come from fewer exports due to the higher prices. But if exports fall enough to meaningfully harm the other country’s economy and deter armed conflict, the tariffs will not raise much revenue.

The thrust of the anti-tariff argument, then is that it is a hidden tax on the American consumer that does not accomplish even its stated goals in rebalancing US trading relationships.

I shall speak to the accuracy of that argument shortly, but first let’s recap the core “pro-tariff” narratives.

The rebuttals from the pro-tariff crowd frequently amount to “you’re wrong.”

Scott Bessent, whose name has been bandied about for a possible role on Trump’s economic team, made that the cornerstone of his defense of tariffs last week.

The truth is that tariffs have a long and storied history as both a revenue-raising tool and a way of protecting strategically important industries in the U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has added a third leg to the stool: Tariffs as a negotiating tool with our trading partners.

Bessent’s core argument is that by opening up trading relations with China, the US has subjected itself to a variety of China’s predatory trading practices, creating issues of both economic and national security.

The U.S. opened its markets to the world, but China’s resulting economic growth has only cemented the hold of a despotic regime. In the interim, we've hollowed out our manufacturing base, leaving a trail of devastation through swathes of our country’s heartland. We've also created key national security vulnerabilities. The truth is that other countries have taken advantage of the U.S.’s openness for far too long, because we allowed them to. Tariffs are a means to finally stand up for Americans.

Bessent flatly rejected the idea that Donald Trump’s tariffs from his first term of office resulted in higher prices to the consumer.

Critics of tariffs argue that they will increase the prices Americans pay for imported goods. This, reduced to absurdity, was the Harris campaign’s "sales tax" argument. But the facts argue against this. President Trump’s first-term tariffs did not raise the prices of the affected goods, despite predictions back then that the tariffs would prove inflationary. Indeed, not only was there no discernible rise in inflation during the last round of tariffs, but the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation actually declined.

John Carney of Breitbart pointed to comments by the CEOs of some of America’s leading retailers (and therefore leading importers) to reiterate the same core argument that tariffs would not result in higher prices.

After the earnings release, Walmart’s chief financial officer said in an interview with CNBC that it was too soon to say what products might increase in price due to tariffs.

“We never want to raise prices,” CFO John David Rainey said. “Our model is everyday low prices. But there probably will be cases where prices will go up for consumers.”

Carney goes on to point out that the major discount chains are themselves engaged in something of a price war, where each one is attempting to undercut the other.

But a closer look at the quarterly results from Walmart and Target suggests that is not the most likely scenario. Walmart’s terrific quarter is not unrelated to Target’s terrible quarter. The largest retailer appears to be taking market share from Target. While Walmart saw strong demand in home products and toys, Target said these were areas of weakness. In other words, America’s biggest retailers are in a kind of zero-sum cage match for customer dollars.

That’s not the kind of situation that gives rise to pricing power. Quite the opposite. If Walmart were to raise prices to preserve its margin on tariffed products, it would be creating an opportunity for Target to take back market share. As Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is said to have remarked, “Your margin is my opportunity.”

In such an environment, Carney correctly notes that retailers are going to have little opportunity to raise prices, and instead would be well advised to source their merchandise from non-tariffed countries. The end result of a tariff strategy could very well be the accelerated decoupling of US firms from supply chains originating in China.

Viewed in this light, tariffs are a net economic good? The answers are “yes”, “no”, and “maybe”.

The basic problem with the “tariffs raise prices” argument is that, for most of Trump’s term of office after the tariffs were imposed, there was a broad decrease in the prices of durable goods, and even non durable goods did not increase significantly, which is easily seen by looking at the Consumer Price Index data for durable and non durable goods during Trump’s first term.

We see largely the same behavior in the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index data for durable and nondurable goods as well, although with much more pronounced deflation among durable goods.

What really confounds the “inflation” argument, however, is the presence of price deflation among imported goods during this same period.

Tariffs on goods are not a cost that needs to “work its way through the economy” to have an effect. Depending on inventory levels and how much product is in the shipping pipeline, the pricing impact of tariffs should occur within a few months at the very latest. Yet nowhere in the pre-COVID portion of Trump’s term of office do we even see rising prices, let alone price increases that can be inferred as the result of tariffs.

And there is an important wrinkle that bears consideration: The (Biden-)Harris Administration not only did not remove the Trump tariffs on China, but increased them.

Democrats and economists alike have demonized Trump's plan, repeatedly criticizing him even during his first administration for his use of tariffs, a "terribly inefficient way of raising revenue," according to James Hines, professor economics and law at the University of Michigan.

Despite those concerns, the Biden administration has maintained $300 billion-worth of Trump's China tariffs and even increased some. The administration in September announced it would add tariffs ranging from 7.5 to 100 percent to Chinese products such as solar cells, semiconductors, medical supplies, electric vehicles and lithium-ion batteries.

What makes this significant, of course, is that the (Biden-)Harris Reign Of Error has been a time of rising prices rather than falling ones.

That is made clear in the Consumer Price Index data:

That is confirmed by the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index data:

That is particularly true of import prices:

If tariffs are indeed that inflationary, creating that much upward price pressure, then the (Biden-)Harris team has been well and truly derelict for not removing them immediately upon taking office.

The argument that tariffs raise prices are lacking one key ingredient: raised prices.

However, we should be cautious about extrapolating from this that tariffs do not exert upward price pressure. If we look at the trend in import prices from 2001 forward, we see that President Trump’s first term coincided with a larger downward trend, particularly among capital goods.

From 2012 onward, import prices were trending down, and did not reverse that trend until after the COVID Pandemic Panic and the subsequent rupturing of global supply chains.

It is quite conceivable—and should be regarded as plausible—that Trump was the beneficiary of a favorable price trend that overcame the expected upward price pressures that would have emerged because of tariffs.

After the hyperinflation of 2022, there should be no presumption of continued downward price trends.

As a matter of economic fundamentals, the anti-tariff adherents are not wrong to say that tariffs push prices upward. By definition, anything that adds cost to any item is an upward price pressure when that item is sold into the market. As tariffs are by definition an additional cost, they necessarily are an upward price pressure.

All things being equal, therefore, the imposition of tariffs should result in higher prices.

The problem is that all things are not equal.

Would removing the Trump tariffs in 2022 have alleviated the hyperinflation of that year? That is at the very least a possibility, perhaps even a probability. Certainly it was something the (Biden-)Harris Administration could have done which might have had more or less immediate effect on at least import prices.

That the tariffs against China were increased might even have contributed in some degree to the hyperinflation.

As tariffs are an upward price pressure, it is easy to consider their influence magnified in a time of rising prices, just as their influence was demonstrably nullified by the falling prices of Trump’s first term.

So what influence would tariffs have, given today’s pricing environment.

We are still seeing goods price deflation overall, in both the CPI and PCEPI data.

However, we are seeing some import price inflation at present.

Imposing tariffs on imported goods at the present time very likely will result in at least some price increase being passed along to consumers. With prices already trending up, adding an upward price pressure would only magnify that existing trend.

With regards to import prices, then, we should anticipate that Donald Trump’s tariffs will result in increased import prices.

Will that translate into increased consumer prices? While that is possible, the existing deflationary environment in goods prices suggests that the upward price pressure of tariffs will be mitigated at least in part by the current deflationary environment. An upward price pressure from tariffs could mean simply that goods prices do not fall as far as they otherwise would.

Will fresh tariffs and a fresh negotating strategy on trade result in better trade relationships with America’s trading partners? That is entirely dependent on the skill and determination of the negotiating team. Without taking anything away from Donald Trump’s negotiation and dealmaking skills, we cannot know how such negotiations will turn out before they happen.

We have reason to be guardedly optimistic about Trump’s dealmaking skills, as they broadly did serve him well during his first term. Still, the future has to unfold as it will, and extrapolations from the past can only carry us so far into that future.

We can say that there are significant downward price pressures in the prices of consumer goods overall at present, and that leaves a measure of “slack” in consumer goods pricing for President Trump to impose fresh tariffs on China without immediate significant inflationary fallout. Arresting the deflationary trend in goods prices might even have salutary effects on the manufacturing sectors of the US economy, as higher prices might help spur growth in domestic manufacturing and domestic production.

However, all such optimistic predictions are just as speculative as the pessimistic predictions of corporate media’s “experts”. They are gaslighting and propagandizing about tariffs, and being fundamentally disingenuous about the first Trump tariffs, and we can know that because what they have said does not align with the “official” empirical data. We do not see tariff-induced price hikes where the anti-tariff argument says we should see them.

At best, that means their modeling of the impact of the Trump tariffs is incomplete. At worst that means their modeling is faked and fictional and not worth a tinker’s damn.

I have no modeling and no predictions, save two: When Trump’s tariffs do get enacted, the immediate impacts will not be anything anyone has forecast, and whatever pricing fluctuations occur, once they are enacted Trump’s tariffs will be blamed by the corporate media for everything, no matter what.

Tariffs are not an economic panacea. They are only effective as part of a robust strategy to ensure the US has vibrant and beneficial trading relationships. Their ultimate impact on prices is ultimately dependent on the prevailing trends in prices before tariffs.

How will Trump’s new rounds of tariffs turn out? There is no way to know for certain in advance, but the prevailing price trends mean Trump has a fair bit of leeway before even the worst tariff strategy seriously impacts inflation.

Radcliffe, B. “The Basics of Tariffs and Trade Barriers.” Investopedia, June 26, 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/08/tariff-trade-barrier-basics.asp.

USTR Press Office. President Trump Approves Relief for U.S. Washing Machine and Solar Cell Manufacturers. 22 Jan. 2018, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2018/january/president-trump-approves-relief-us.

The Investopedia Team. “Dumping: Price Discrimination in Trade, Attitudes and Examples.” Investopedia, Aug. 22, 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/dumping.asp.

Berstein , J. “What Are Tariffs and How Do They Affect You?” Investopedia, Oct. 18, 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/news/what-are-tariffs-and-how-do-they-affect-you/.

Great topic, Peter, and timely. As always, you provide data to substantiate every point of your discussion - a very intelligent and impressive feature I see in few other Substacks, so, thank you! I also agree with your ‘it depends’ assessment.

Policy-makers forget that any attempt to get around free-market mechanisms inevitably results in ‘unintended consequences’. With tariffs, you risk increases in smuggling, buying and selling on the black market, and the organized crime that prospers as a result. So, tariffs have to be thought through and applied carefully. For example, If Trump plans to Impose a high tariff on Chinese silicon chips, he could first notify domestic chip manufacturers, then give them tax credits to spur initial domestic investment, and wait to impose the tariffs until domestic manufacturers are just about up and running. Or, he could negotiate a deal with Mexico that would result in chip manufacturing there, in exchange for their increased vigilance against illegal immigration at the US/Mexico border. The key is: think it through!

And then there is the problem of increased bribery. The US doesn’t have a culture of bribery, so we forget that much of the world runs on bribery. The last time you went to get your driver’s license renewed, it didn’t even occur to you to offer a bribe to the DMV, right? That is not the case in many of the countries we do business with, and we certainly don’t want to enable a bribery-oriented business climate here!

This reminds me of an article I read in the Wall Street Journal forty years ago (back when it was still real journalism). The article was an assessment of which cities were the most expensive for western businessmen to visit, and usually it came out that Tokyo, New York, or London was most expensive. But this particular year, Lagos, Nigeria was the most expensive! Puzzling - until you looked at all of the bribes you had to pay. Any western businessman was assumed to be rich, so he or she was hit up for a bribe at every step of the visit. You had to pay a bribe to get off the plane, a bribe to enter the terminal, a bribe to retrieve your luggage, a bribe to get a taxi, and so on, all day long.

We don’t want that.

Excelent discussion.

Thank you.