Is China's Deflation Increasing? Or Has It "Bottomed Out"?

How Much More "Collapse" Is Left?

How can we be sure that China is spiraling deeper into deflation? Simple: Beijing openly admits it.

China’s consumer prices slid deeper into deflationary territory last month, suffering their biggest drop since the global recession in 2009 and underscoring the huge challenges facing the economy.

The country’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) dropped by 0.8% in January from a year ago, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) on Thursday. It was the steepest fall since September 2009 and marks a fourth straight month of decline.

It is unlikely that Beijing would admit to ongoing deflation if there was any way to spin the data otherwise, especially given their long-standing reputation for economic mendacity.

Subject matter experts have long questioned the veracity of Beijing's economic reports in general, including former Chinese premier Li Keqiang, who in 2007 dismissed his country's economic data as "man-made."

Nor is it just consumer prices which are showing persistent declines. China’s Producer Price Index notched its sixteenth straight month of declines in January.

In other data published on Thursday, factory gate prices also fell, with the producer price index slipping 2.5% in January from a year ago, compared with a 2.7% decline in December, a modest improvement but underscoring weaker energy prices and subdued domestic demand.

There is no question that the Chinese economy is mired in deflation, and that it has been mired in deflation for some time now. What is a question is whether this deflation is becoming an economic “death spiral” or whether a rebound is imminent.

While analysts and China watchers acknowledge that China has been in a deflationary phase, there is still a prevailing narrative of “rebound” and “recovery” being just around the corner.

China’s economy first entered deflation last summer, with prices falling at a faster pace since then. Its factories have also cut prices, with the latest producer price index pointing to a 2.5% drop in annual prices in January, after a 2.7% fall in December.

However, ING’s chief economist, Lynn Song, said it was worth noting that the latest data may be skewed due to the fact that lunar new year falls in February, rather than January, this year. It means that household demand for food such as pork could bounce back once next month’s data takes the holiday season into account.

“While a far cry from the above-target inflation levels seen in many other economies, these numbers do not imply China is stuck in a deflationary spiral,” Song said.

“Considering the more favourable base effects for February’s data, we see a high likelihood that January’s data could mark the low point for year-on-year inflation in the current cycle,” she added.

One reason for this belief is the sentiment on Chinese bourses, just as on Wall Street, that the grim economic data means Beijing will be forced to do more fiscal and monetary stimulus to prop up the economy.

However, the prospect of fresh economic stimulus from Beijing to counter weaker demand was enough to send Chinese stocks higher on Thursday, with the Shanghai Composite rising by nearly 1.3%.

“While a very concerning sign for China’s economy, which could be becoming entrenched in a debt and deflation cycle, the markets arguably responded in a positive way to the news,” said Kyle Rodda, senior financial market analyst at capital.com.

“Perhaps markets see the terribly low number as a potential catalyst for more muscular monetary or fiscal stimulus from the central government, which, up until this point, has been moderate in applying countercyclical policy.”

Economist Michael Pettis, Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment, summed up the case for China optimism in a series of tweets.

The crux of the case for optimism is simply that the numbers are not as bad as they might first appear, and that there are signs of things will turn around due to the stimulative effect of the Lunar New Year holiday.

Yet what do the numbers really say?

One challenge to the “turnaround” narrative is the reality that China’s economic data has been less than stellar for a number of years, stretching well back before the Zero COVID lockdowns which began in 2020.

Export growth was already showing signs of hitting a plateau (and potentially stagnating) as early as 2013.

While exports genuinely surged in 2020 and 2021, from early 2022 onward that surge has been steadily receding.

Import growth shows a similar pattern—largely plateaued or posting minimal growth from 2013 through 2019, followed by a post-pandemic surge which is now receding.

We should also note that China’s factory gate prices were showing deflation as early as 2019.

While producer prices did recover and even grow in 2021, by early 2022 that growth had run its course, and factory gate prices have been moving down ever since. As a rule, factory gate prices are a leading indicator to consumer prices, and when there is a strong deflationary signal in factory gate prices—such as what we have had in China since early 2022—the general presumption for consumer prices is also going to be deflation.

Moreover, China’s factory gate prices have posted three significant periods of deflation since 2013.

While the middle one can arguably be traced to the COVID “pandemic” and the resultant economic lunacies imposed by Beijing, the deflation in 2013 through 2016 and the current deflation cannot be explained away by that rationale.

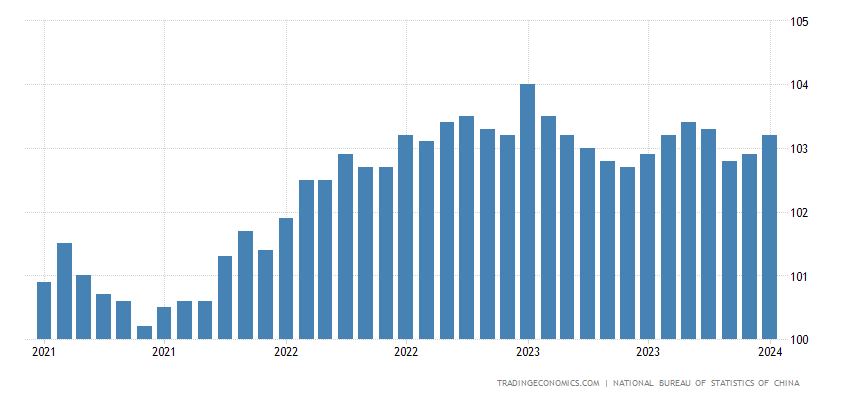

Similarly, China’s consumer prices peaked at the beginning of 2023, and have been declining ever since.

Yet even with that relatively late peak in consumer prices, inflation—the rate at which consumer prices rise—peaked far earlier, in the initial lockdown period during 2020.

While inflation rebounded somewhat during 2022, by late 2022 disinflation had set in, which turned into outright deflation in late 2023.

However, if we peel back the layers and look at China’s core consumer prices (in every country, core consumer prices are with food and energy prices stripped out, as they are typically far more volatile than other prices), we see that core consumer prices peaked all the way back in 2018.

As a consequence, China has had core consumer price deflation in various months since 2018.

Contrary to the narrative that China has only recently entered deflation, the reality is that China’s consumer prices, much like its factory gate prices, have been displaying significant softness even extending back before 2020 and the Zero COVID lunacies.

Perhaps the biggest indicator of China’s latent economic weakness is the fact that China’s export prices experienced an extended period of decline in 2018 and 2019.

Only the Zero COVID lockdowns temporarily reversed that decline, and even though export prices reached a peak in 2022, they have collapsed considerably since.

The export price decline has been helped along by a similar decline in import prices.

We must note, however, that import prices are the one area where deflation is not the narrative of the moment, as import prices have staged a mini-recovery in recent months. Will the rise in import prices (which are in turn input prices for Chinese exports) be enough to bring some upward price pressures on exports and on consumer prices? That is a possibility, although we have not seen any indication of that happening yet.

The singular flaw in the optimistic narrative on China deflation is that it relies too heavily on the most recent data and ignores longer trends which extend back before the time of Zero COVID.

It is tempting to ascribe most if not all of China’s recent economic woes to COVID and the Pandemic Panic mistakes and lunacies which ran roughshod over China’s economy from 2020 onward. However, regardless of the very real damage done by China’s Zero COVID policies, the reality remains that there were significant signs of economic weakness well before the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerged from a Wuhan lab. The dislocations and rebounds brought on by Zero COVID may have helped to postpone confronting the weaknesses that were already starting to show in China before COVID emerged, but it was never going to erase those weaknesses and give China the option of ignoring the many structural flaws in its economy.

The awkward reality of China’s economy is that deflation was a major risk in 2019, and only the dislocations and disruptions of Zero COVID from 2020 through 2022 succeeded in postponing the realization of that risk. With Zero COVID having faded from the scene over a year ago, the same forces that were pushing China towards a deflationary crisis are once again rising to the top, and are once again pushing China towards a deflationary crisis.

Is China’s deflationary episode soon to be over? While there is always a possibility that such will be the case, it is far more likely that, as the pre-pandemic forces continue to gather, deflation still has some ways to go before it is through tormenting the Chinese economy.

The deflation cycle in China will end, and may even end this year. However, we should not look for this deflationary episode to turn the corner and move the Chinese economy into a true rebound and recovery phase any time soon. It is far more likely that China will see further deflation in January 2025 than resurgent inflation.

China is not yet hit bottom. More pain is yet in store for the Middle Kingdom.

You were the first analyst I know of to spot China heading into deflation, so kudos, Peter!

And wasn’t “recovery is just around the corner!” the rallying cry of American politicians in 1933? Ha!

Two questions and a request:

One graph shows three periods of deflation in factory gate prices. Do you have any reliable information (I.e. not Chinese propaganda) to explain how exactly the late-2016 situation got out of deflation? I’m looking for tactics that China might successfully employ again.

Also, if the Hong Kong stock market plunges upon reopening, and stays down, how would you expect that to affect the deflationary trend? Drastically increase the rate of decline?

The request: an interesting column you could write, if you’re interested, would be to contrast Japan’s deflationary periods with China’s. Now, I realize they are much different economies, so it would indeed be comparing apples with oranges. Still, it might give clues of trends to come. After Japan’s CPI had four straight months of decline, what happened in the fifth, and sixth, and one year later? After Japan’s PPC had sixteen straight months of decline, how did it trend afterward?

Thank you, Peter!

This may be of interest to you:

https://www.theepochtimes.com/opinion/why-china-cant-solve-its-problems-of-today-5586693?utm_source=ref_share&utm_campaign=copy