Is the Russia Price Cap Starting To Fail?

Russia May Have Found A Way To Circumvent The Cap

At the end of January, I posed the question “Will The Oil Cap Hold?”

It is beyond any and all doubt that the price cap has curtailed Russia’s oil revenues over the past two months, prompting a belated pushback from Vladimir Putin in the form of a threat to curtail oil production if the cap is sustained.

However, as the world moves further into 2023, a question arises: how long can the oil price cap hold?

The answer may prove to be “not much longer”.

As of this writing, we are seeing indications that “not much longer” may be “right now”.

The most significant indicator we have that the price cap is starting to crumble is the spot market price for Russia’s benchmark Urals crude oil blend, which on March 1 Trading Economics recorded as closing at $60.27/bbl—above the price cap for the first time since January 20. The price subsequently retreated barely below the cap to $59.89/bbl.

This was also the closing price found at Investing.com.

Most notably, the surge in the price for Urals crude exceeds recent price increases for the global benchmark Brent crude.

Whatever market forces are pushing the price of Urals crude up, they are distinct from the price pressures affecting Brent. This shift in the broad price dynamic between Urals and Brent has to be viewed as an indicator that the price cap is either breaking down or may be about to break down.

Certainly, one likely factor for the sudden surge in the spot price for Urals crude is the commencement of Russia’s 500,000bpd production cut.

Russia starts reducing its oil output by 500,000 barrels per day (bpd) from March 1 in a one-month production cut that is intended to “stabilise the market,” according to Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, who added the decision had been taken voluntarily without consultation with OPEC+ countries.

While the prevailing wisdom on the production cut is a tacit admission that Russia is having difficulties finding customers for its hydrocarbon exports, there remains the possibility that Russia is testing market reaction to a decision to withhold production volumes. This theory rests primarily on estimates from some sources (e.g., bne IntelliNews) that Russian oil production in February topped 11 million bpd.

However, in February Russia’s oil production not only remained steady, but climbed back to over 11mn bpd, higher than the level of production on the eve of the start of the Russo-Ukraine war a year ago. Moreover, as bne IntelliNews reported, it seems that with somewhere between 400-600 tankers in its growing “ghost fleet” Russia has the logistical capacity to carry all its output to non-aligned markets.

We must be cautious with these figures, however, as the 11 million bpd figure is significantly above both Russia’s agreed-upon OPEC+ production target of 10.46 million bpd and its reported sustainable capacity of 10.2 million bpd per the International Energy Association.

With January’s production having been down around 9.77 million bpd not counting condensates, the surge to 11 million bpd (with condensates?) is a dramatic surge in output, made all the more remarkable by Russia’s October admission that it was having technical difficulties ramping up production, which at the time was at 10.77 million bpd including condensate.

The Russian Federation failed in October to increase oil production, which so far remains at a level of no more than 1.47 million tons per day, taking into account the production of condensate, sources familiar with the situation told Kommersant. The export of Russian oil by sea and oil pipelines decreased by almost 2% compared to September, to about 640 thousand tons per day.

If the IntelliNews estimate of 11 million bpd includes condensates, Russia’s actual production of crude in February may be considerably less (the IEA estimates for February will not be available for a couple of weeks yet).

Moreover, reports of crude oil shipments from Russia to other oil exporting countries such as Ghana strongly suggest Russia is having to search far and wide for customers to take its crude.

A cargo of Russian oil is heading for storage tanks in Ghana, a nation that exports crude itself and is on the doorstep of two regional supply powerhouses.

The development suggests that traders could be scouring the market for new buyers of Russian barrels after the European Union stopped almost all seaborne imports from the country in December. The bloc’s measures made Moscow hugely reliant on Chinese and Indian purchases.

If Russia is having to look far and wide for new customers for its oil and refined products, the likelihood Russia can manipulate global oil prices declines significantly.

Other indicators the price cap is not having the desired effect include a paper1 published on the Social Sciences Research Network (SSRN) which argues Russia is commanding an actual price for Urals crude in excess of the spot market price, and that the true benchmark average for Russian crude is closer to $74/bbl rather than the latest Urals closing price of $60.27/bbl.

Surprisingly, we do not find crude oil discounts as large as those reflected in Urals prices: in the post-embargo/price cap period, the average export price for Russian crude oil stood at around $74/barrel based on our data—compared to Urals at $52/barrel.

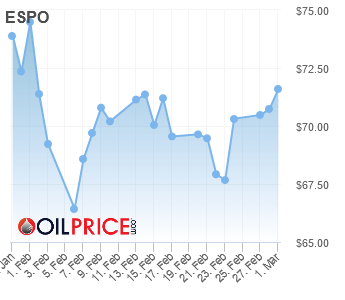

The higher price for Russian crude assessed in the Babina paper suggests—as does Intellinews—that the Urals contract is no longer the benchmark price for Russian oil. Instead the ESPO contract is now the more meaningful gauge of Russian oil pricing. $74/bbl is a price more reflective of ESPO rates.

A crucial distinction of the ESPO contract which bears significantly on the price cap is where the crude is transshipped. Urals crude is transshipped at Western ports of Primorsk and Ust-Luga on the Baltic Sea and Novorossiysk on the Black Sea, whereas ESPO is transhipped at Russia’s Pacific Coast ports (primarily Kozmino near Vladivostok).

As cargoes leaving Russia’s Pacific ports do not require transit through regulated waterways such as the Suez Canal, they are effectively outside of the price cap regime. Accordingly, the price for ESPO crude has always remained above $60/bbl, even as the price for Urals crude fell below $60/bbl.

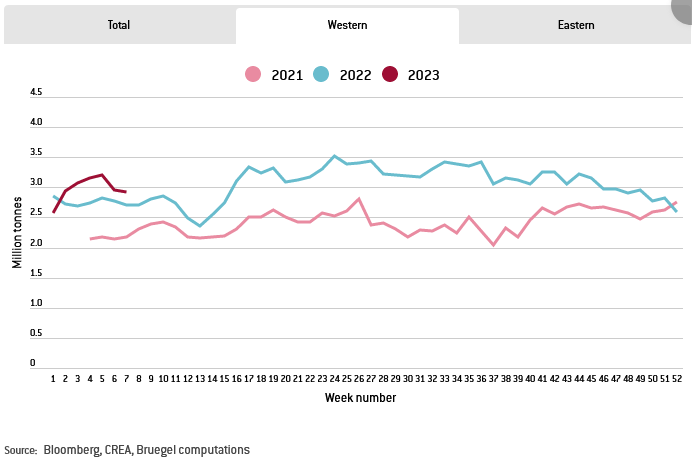

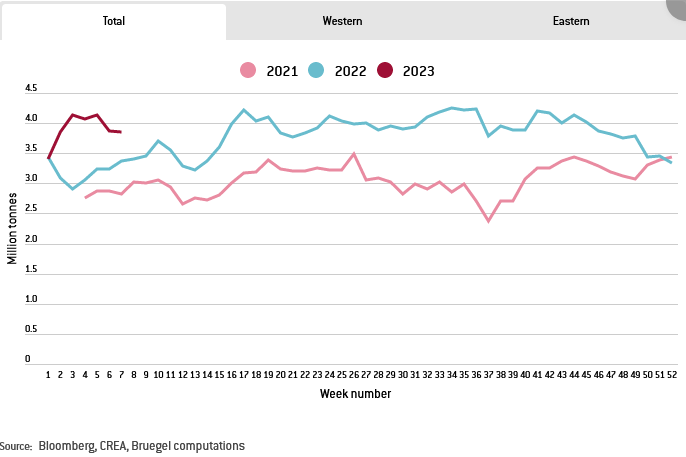

If the ESPO contract is taken as the benchmark for Russian oil, that also would signify a shift in Russian oil export activity from Russia’s western ports towards the eastern ports. As of this writing, however, such a shift is difficult to argue based on the broader shipping data. According to European think tank Bruegel, oil shipments from Russia’s western ports have recently been around 3 million metric tons per week.

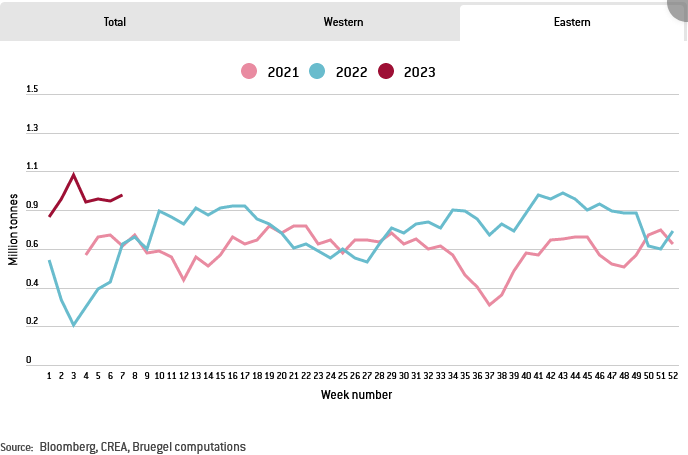

Eastern port traffic, on the other hand, has largely not exceeded 1 million metric tons per week.

Moreover, while shipments are up from both western and eastern ports over 2022, they have declined significantly in recent weeks.

Russia’s Pacific ports may become their primary oil export terminals in the future, but that shift has not happened yet.

Part of this is due to the capacity limitations of any port. Space is finite, as is pipeline capacity for oil terminals within any port. Thus Kozmino, the primary terminus for the ESPO pipeline system, can transship approximately 1.6 million bpd2 of crude and refined products at most. Primorsk can transship approximately 1.5 million bpd. Ust-Luga can transship approximately 600,000 bpd. Novorossisyk in 2021 transshipped approximately 1.85 million bpd.

In other words, the western (Urals) ports have between three and four times the capacity of the eastern (ESPO) ports. This capacity imbalance is not going to change any time soon, simply because of the layout of Russia’s pipeline networks, which heavily favor western over eastern destinations.

The ESPO crude price is not insignificant, nor is the fact that it sits largely outside the enforcement reach of the EU/G7 price cap. Whether it can be applied to enough crude volumes to stand as a legitimate benchmark, however, is at the very least problematic.

Another indicator that Russia is circumventing the price cap is the apparent growth of a “ghost fleet” of tankers owned directly by Russia and which appears to have been taking on an increasing proportion of its seaborne oil traffic.

As Western sanctions against Russia have escalated over its invasion of Ukraine, more ships have joined an existing fleet of mysterious tankers, ready to facilitate Russia’s oil exports.

Industry insiders estimate the size of that “shadow” fleet at roughly 600 vessels, or about 10% of the global number of large tankers. And numbers continue to climb.

Russia has been building up this ghost fleet since before the crude oil price cap took effect.

The Russian-owned fleet of ships is potentially large enough to handle most, if not all of its oil export requirements, and the Russian government is in effect underwriting the fleet’s insurance needs.

State-controlled Russian National Reinsurance Company (RNRC) is now the main reinsurer of Russian ships, including Sovcomflot's fleet, after Western insurance firms withdrew cover for Russian shipowners, three people familiar with the matter told Reuters.

In theory, this fleet allows Russia to ignore the price cap and charge market rates for its oil, something IntelliNews assesses is happening.

Over the last year Russia has been increasingly setting up these services as a way to bring the price it is paid for providing oil without increasing the cost of Urals. For example, it has been widely reported that Russia is operating a “ghost fleet” of tankers for which it can charge (chart). According to recent reports there could now be more than 600 ships in this fleet – enough to carry all of Russia crude and oil production to non-aligned markets.

In essence, Russia is working to replace the lost oil revenue from the price cap with ancillary revenues from providing the shipping logistics necessary to deliver the oil to the end customer. By capturing the logistics revenue, Russia in theory can recover a significant portion of the oil revenue lost to the cap.

These various add-on services and charges can amount to as much as an extra $25 per barrel, bringing the “discounted” Urals price per barrel up to close to the cost of a barrel of Brent.

Taking these extras into account Vakulenko estimates that the actual cost of a barrel of Urals is closer to $75 than $50.

While assessments of the degree to which Russia is exploiting this means of cap evasion suggest the volume of crude traffic is significant, the revenue generated is not cost free. Even with Russian companies providing the necessary insurance certificates, shipping and logistics expenditures are not eliminated simply by owning a tanker fleet—if that were the case every oil-importing nation would seek to own its own fleet of ships on economic reasons alone.

On the open market shipment costs of Russian oil to India varied between $11 and $19 per barrel of oil in 2022, a marked increase from previous levels of around $3 per barrel. While Russia’s “ghost fleet” presumably is bringing much of that cost within the reach of the Russian Ministry of Finance as taxable revenue, it still has to fund the underlying activities of that cost: crewing ships, fueling ships, maintaining ships, et cetera. It would be unlikely if much more than half of those add on charges remains as profits after these expenses, thus incorporating the entirety of those add on charges into the overall price of Urals crude is likely overstating the revenue effects considerably. They do provide a revenue enhancement, but that enhancement is unlikely to be the assessed $25 per barrel.

Consequently, even if Russia has found a means to secure revenue streams which come close to pre-war market rates for Urals crude—pre-war the Urals discount to Brent was around $1-3/bbl—the costs incurred in the process mean the cap’s ultimate objective is still being reached: the Russian government is not getting the revenue from oil it previously did.

That doesn't mean the missing money is ending up in the Kremlin's coffers. The Russian budget did tumble in January to a RUB1.8 trillion deficit and Ministry of Finance (MinFin) reported that oil and gas revenues were down 46% year on year in January, but what appears to be happening is Russia’s oil companies are reporting lower Urals prices, which reduce their tax burden, but are making back the discount through various scams. Money is being siphoned off into dark company-controlled offshore accounts in, what is in effect, a new transfer pricing scheme. MinFin is well aware of what is happening and is already working to tap into this dark flow of profit.

Nor should it be overlooked that, by most customary metrics, Russian oil revenues have fallen. The Centre For Research on Clean Energy And Air has assessed the impact of the price cap and sanctions on Russia’s oil revenues as amounting to €160 million per day, resulting in a 17% drop in earnings for Russia in December. Between November and February, Russia’s daily revenues from fossil fuel exports are believed to have fallen from $844 million to $551 million, and projected to fall still farther.

Even the Babina paper concedes there has been a substantial revenue impact to Russia as a result of the various sanctions as well as the price cap.

What should not be overlooked, however, is that the sizable discount on Russian crude oil during most of 2022 reduced the country’s export earnings considerably. Although the EU embargo and G7 price cap were not implemented until December, Russia had to accept significantly lower prices to maintain export volumes. We estimate that the widening spread between Russian export prices and Brent crude, which soared to above $30/barrel in April-May (see Figure 3), shaved off more than $30 billion—or above $3 billion per month from crude oil exports compared to a scenario in which Russia received close to market prices

Even if the price cap should fall apart now, it has already cost Russia a considerable amount of hydrocarbon revenue. It is likely to continue to cost Russia considerable amounts of lost revenue for as long as it holds.

Perhaps the most significant consequence of the price cap and Russia’s efforts to evade it is the fragmentation of the global oil market. Russian oil is rapidly becoming a market unto itself, and countries are left to choose whether to buy oil on the Russian market or on the global market.

This bifurcation of oil demand may very well be a contributing factor to the continued downward trend in the price of Brent crude even in the face of Russia’s production cuts. Simply put, as countries choose to buy Russian oil they are shifting not just revenue but also demand away from the global market, and thus the upward pressure from demand on the Brent price is falling.

The unmatched surge in the spot price for Urals crude may also be an early indicator of this fracture.

What this means for the economics of the oil industry is a question that will be years in the answering.

A fracturing of the global oil market, however, is a fundamental disruption of the western-led “rules based” economic order that is foundational to the global economy as it exists today. Separating the market for Urals and ESPO crude from the market for Brent and other benchmark blends segregates the world not just geopolitically but economically.

This economic bifurcation would eliminate the arbitrage3 practices which work to equalize oil prices globally—and which translate into price trends for various crude blends largely following each other. Energy costs would acquire a geopolitical element they do not have currently, and energy markets would become a good deal less efficient as a result.

Moreover, any such bifurcation necessarily means a smaller market for everyone. If markets become geopolitically defined then every producer nation has fewer potential customers than they do now, and fewer opportunities to export anything. There’s no way for it to be otherwise. The moment countries decide not to sell to other countries for reasons disconnected from the economics of buying from and selling to other countries, markets immediately shrink—and there is not an economic scenario where shrinking markets end well for anyone.

Russia is naturally doing all that it can to evade oil sanctions and the price caps being imposed on its oil exports. There are now growing signs that they are at least to some degree starting to succeed. Whether this is sufficient to break the cap so that the spot price for Urals crude rises well above $60/bbl remains to be seen, although there are signs Russia’s efforts are yielding fruit in pushing through the cap at least temporarily.

Whether the result of Russia splitting off into its own energy and hydrocarbon market, distinct from the global market, proves a net benefit to the Russian economy as a whole is a far more problematic question. At the present time, that bifurcation appears a net loss and not a net benefit to Russia.

Babina, T., et al. Assessing the Impact of International Sanctions on Russian Oil Exports. Social Sciences Research Network. 23 Feb. 2023, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4366337.

The conversion rate to calculate the number of barrels of crude oil in a metric ton is approximate, as the density of various crude blends differs. However, a conservative approximation is 7.33 barrels of crude oil per metric ton. While port capacities are frequently given in metric tons (also spelled “tonnes”) annually, daily capacities are easily obtained by multiplying by 7.33 and dividing by 365.

Fernando, J. Arbitrage: How Arbitraging Works in Investing, With Examples. Investopedia. 1 Dec. 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/arbitrage.asp.