On Monday, December 5, the cap on Russian oil devised by the EU and supported by the G7 group of nations took effect.

While the dynamics of the price cap and its impacts on oil prices will be constantly unfolding for the next several weeks if not months, it is not too soon to assess oil prices and volumes to see if the cap is having the desired impact of curtailing Russian oil revenues.

Looking at the totality of the data available thus far, an argument can be made that the cap is having at least some limiting impact on Russian oil revenues

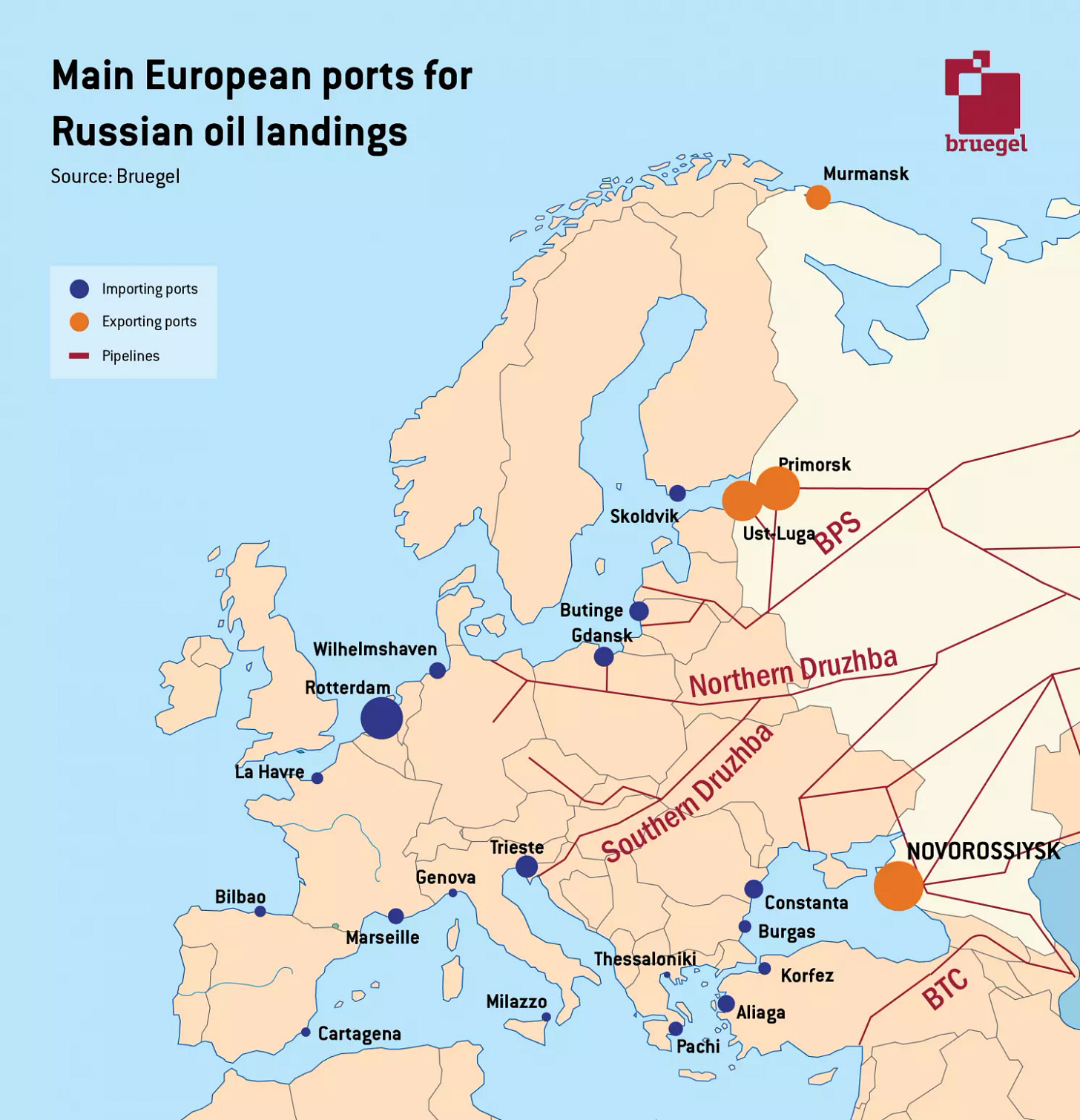

As the map above shows, the three main European ports from which Russia exports crude oil are Novorossiysk on the Black Sea, and Ust-Luga and Primorsk on the Baltic Sea.

Straight away, we can see from the map that Russia’s European ports can potentially be blocked at natural choke points: the Bosporous and Dardanelles straits connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, both of which are controlled by Turkey under the 1936 Montreaux Convention1, and the Danish Straits, which, while technically Danish-Swedish-German territorial waters, are regarded as international waterways under the Copenhagen Convention of 18572.

The price cap, which forbids western insurance and financial services companies from insuring or facilitating any shipment of Russian oil sold above a price of $60 per barrel from December 5, 2022, onwards, thus has natural enforcement points which can potentially prevent Russian oil from accessing the open ocean en route to their ultimate customers, even from outside the EU and the G7 group of nations. For this reason alone, the cap must be presumed to be at least somewhat enforceable (although what the impact would be of ships using Chinese, Indian, or even Russian insurance documents in lieu of western insurance documents is as yet an open question).

Turkey is in fact giving the world a perverse demonstration of how effective this regulation can be at interdicting oil shipments, as it has singlehandedly created a shipping logjam by demanding confirmation of maritime insurance coverage before allowing any oil tankers through Turkish waters to exit the Black Sea into the Mediterranean.

A traffic jam of oil tankers has built up in Turkish waters after western powers launched a “price cap” targeting Russian oil and as authorities in Ankara demanded insurers promise that any vessels navigating its straits were fully covered.

Under EU sanctions which came into effect on Monday, tankers loading Russian crude oil are barred from accessing western maritime insurance unless the oil is sold under the G7’s price cap of $60 a barrel. The cap was introduced to keep oil flowing while still crimping Moscow’s revenues.

As of week’s end, the number of ships held up in this fashion had grown, despite EU insistence that Turkey is overreacting to the strictures of the cap.

The number of oil tankers idling in the Bosphorus and Dardanelles Straits waiting to enter Turkish waters has swelled to 28 as of Friday, compared to 20 on Monday.

Before they can move on, Turkey requires all oil tankers to show proof of proper insurance coverage for their cargo, in light of the recently implemented G7 oil price cap on Russian crude.

Turkey’s requirements come despite Western assurances that not every crude oil tanker should have to prove that it has proper coverage. The insurance checks are creating extensive delays in shipping, and is worrying not only crude oil buyers, but Russia as well.

While Turkey’s exactitude is creating administrative headaches for ship captains, ship owners, and maritime insurers alike, that the tankers are bottled up by it is pretty conclusive proof that the price cap can keep Russian crude from reaching its ultimate customers simply by policing these waterways in between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and the Baltic Sea and the North Sea as well.

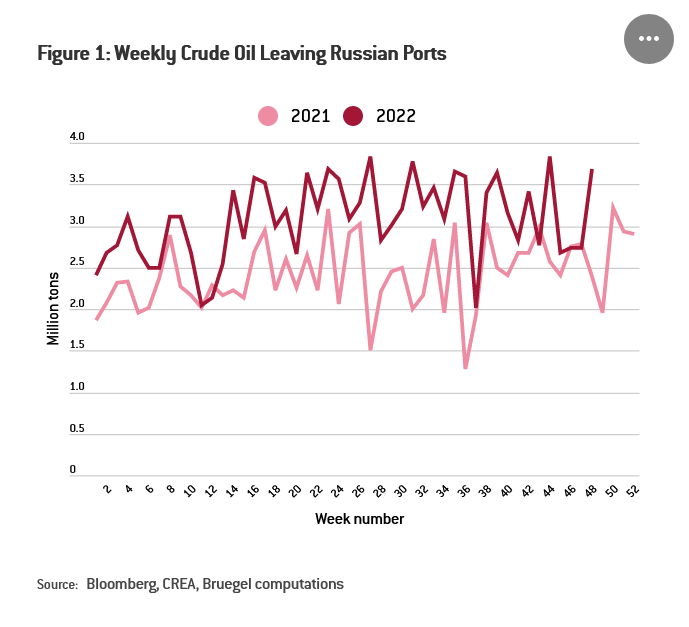

One might even assess that last week’s spike in oil shipments leaving Russian ports can be attributed to last minute “panic buying” of Russian crude ahead of the cap.

Prior to that last minute surge, while there was a distinct rise in Russian oil shipments during the summer, by November there was a decided dropoff, presumably as either shippers or buyers began to get nervous about the price cap and began curtailing Russian oil purchases ahead of the cap taking effect.

The shipping volumes alone indicate the cap is having an impact on Russian oil transactions. Is that impact curtailing Russian oil revenues?

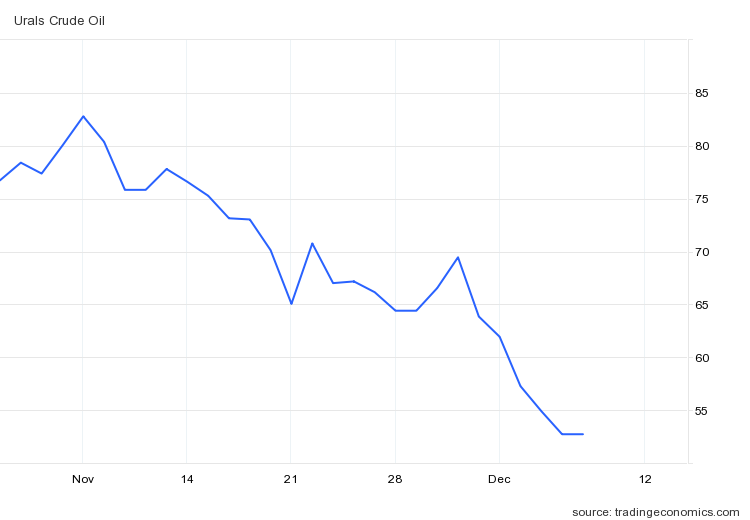

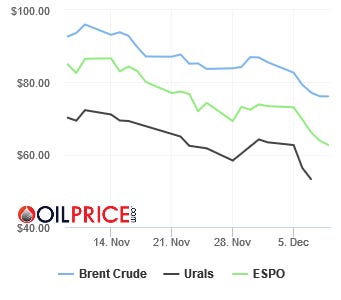

Arguably, yes. In the week since the cap took effect, the price of Urals crude has dropped below the cap level of $60 per barrel, and as of this writing has settled at $52.72 per barrel.

While the price of Russia’s benchmark Urals crude had been declining throughout November, from December 5 onward there is a marked acceleration in the decline, which suggests the cap has indeed had an effect on the price

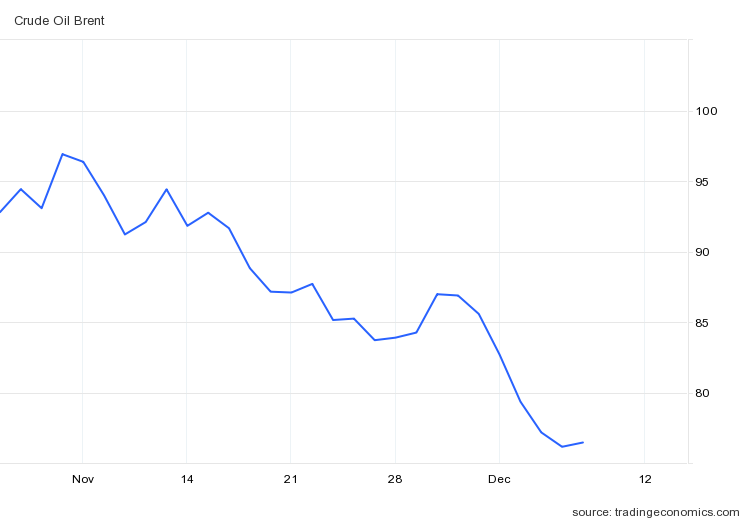

It should be noted, however, that Brent crude has also been declining, although there is not a discernible acceleration in the decline on December 5. As of December 8 the settlement price for Brent crude as $76.15 per barrel.

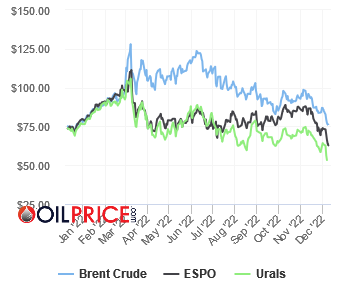

Thus Urals crude continues to trade at a $20-25 discount from Brent crude—a discount that was not in effect prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February.

We should also keep note that Russia’s other major crude blend, ESPO (delivered via the East Siberia Pacific Ocean pipeline to Vladivostok and Kozmino), has recently been trading at a much smaller discount to Brent crude, and is currently trading above the price cap, with the December 8 settlement at $63.87 per barrel (a discount to Brent of $12.28 per barrel).

One of the complicating factors in assessing the actual efficacy of the price cap is that, while there has been a fair bit of volatility in oil prices throughout the year, the price predictions made by Goldman Sachs and other market watchers have largely failed to materialize. In March Goldman predicted Brent crude would rise to $135 per barrel, but the actual price never rose above $123.48 per barrel, and has not been above $100 per barrel since the end of August.

The “worst case” predictions of $200 per barrel oil prices have never even come close to being a reality—at least, not yet.

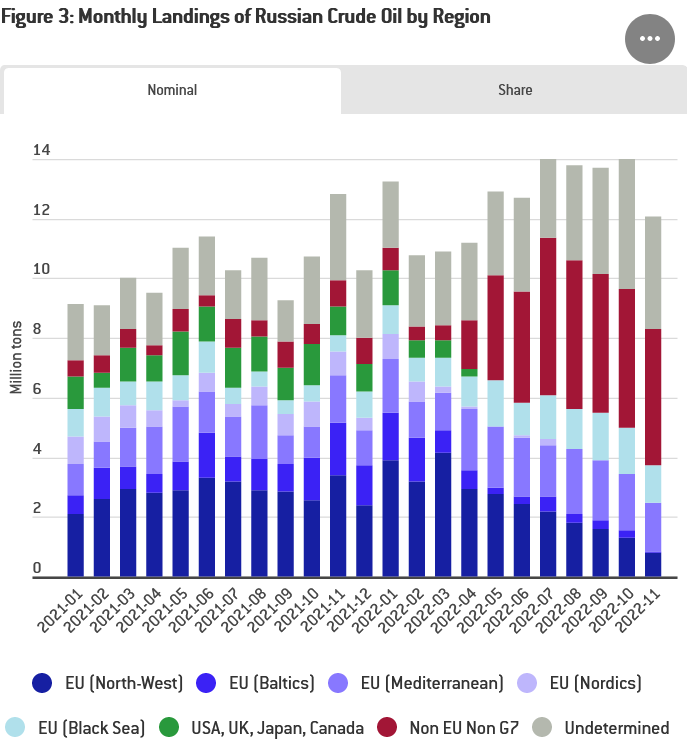

As the volume charts above indicate, this is in part because actual volumes of Russian oil shipped have actually been higher in 2022 than in 2021, with substantial deliveries continuing to be made to the various EU segments, although EU purchases declined right before the imposition of the cap, and, concurrent with the cap, the EU enacted a total embargo on Russian oil purchases by EU member countries.

In addition, traders calculate that further central bank interest rate increases, aimed at curbing inflation, may hobble economic growth around the globe and reduce demand for oil. Such concerns are coupled with an assumption that China, the world’s largest energy importer, will rev up its economy only gradually, despite an easing of Covid restrictions.

One could make the argument that, as market forces have driven the price of Urals crude below the price cap, the cap itself is not having any actual impact on Russian oil revenues. While this may very well be the case, it is also the case that after the cap was imposed, the discount obtainable on even the ESPO blend increased from $9.59 per barrel on December 5 to the latest $12.28 per barrel.

While the timing alone is not conclusive proof the price cap drove the increase in the discount, the timing does make it impossible to dismiss the cap out of hand.

The price data makes one thing absolutely certain: regardless of the cap’s actual efficacy, at the present time Russia’s oil revenues are declining simply by virtue of the current market slump in oil prices, regardless of the driving force behind the decline.

That the price of Urals crude has fallen below the cap leaves Putin with an awkward problem: Putin and his inner circle have stated repeatedly that they would not recognize the price cap and would not sell oil to any buyer intent on respecting the price cap. This implies that Russia will not sell oil at any price below the cap price of $60 per barrel. Yet if Putin follows through on that implied threat Russia has to halt all sales of Urals crude (and potentially ESPO as well, depending on what that blend’s price does in the coming days), Russia’s oil revenue drops to zero.

Even if the price of Brent crude surges as a result of the withdrawal of Russia’s oil production from the market, Russia would get no benefit. Agreeing to sell Urals crude would only cause the price to drop again—arguably back below the price cap, putting Putin back in the same awkward place.

The stated goal for the price cap is to limit Russia’s oil revenues going forward, and thus limit Putin’s ability to fund Russia’s war in Ukraine. The steep drop in the price of Urals crude is certainly achieving that result, and gives the EU and the G7 group of nations the opportunity to claim that the cap is working—and, politically speaking, that is all the EU really needs.

Even if the cap ultimately does not hold (and, given time, the cap is almost sure to fail, once Russia finds a way to sell and deliver oil above the cap price), for now the EU can claim success, and for now Russia is facing reduced oil revenues, which will make funding the war in Ukraine increasingly challenging for Putin.

That is enough to give this round in the ongoing economic war between the EU and Russia to the EU. For now, the price cap is doing what it is supposed to do.

Convention regarding the Regime of the Straits". United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office

"Western assurances that not every crude oil tanker should have to prove that it has proper coverage."

Turkey: If you're going to ask us to make SOME people's tankers prove they have proper coverage, then it's only fair that everyone's tankers will have to do the same.