It is without a doubt nothing short of remarkable that the oil price cap imposed on Russian Oil by the EU and G7 nations has endured this long.

It is beyond any and all doubt that the price cap has curtailed Russia’s oil revenues over the past two months, prompting a belated pushback from Vladimir Putin in the form of a threat to curtail oil production if the cap is sustained.

However, as the world moves further into 2023, a question arises: how long can the oil price cap hold?

The answer may prove to be “not much longer”.

As I noted previously, one immediate effect of the price cap has been to increase the discount applied to Russia’s benchmark Urals Crude oil, adding between $8/Bbl and $10/Bbl to the discount that had emerged following Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

At the same time, I noted one important detail that deserves further exploration: The price cap was actually (albeit briefly) breached.

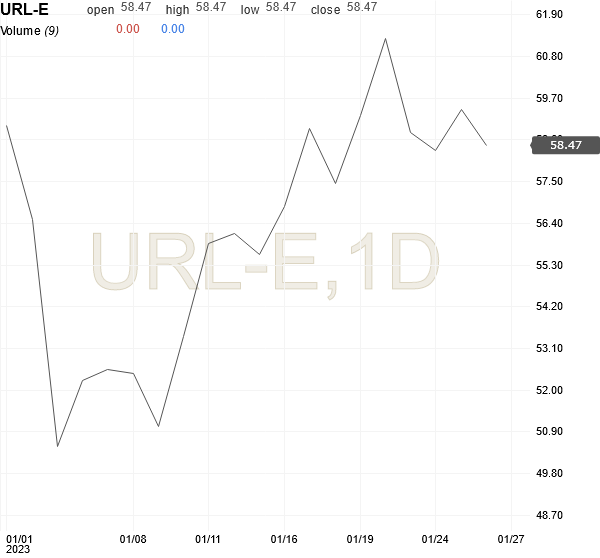

It should be noted, however, that since January 10, the spot price of Urals crude has been steadily rising, and on January 23 actually closed above the price cap, at $61.28/Bbl.

While Urals Crude quickly retreated back below the cap, rising oil prices are pushing the spot price right up against the cap.

Nor was Trading Economics the only pricing platform to record the breach. Investing.com’s review of Urals Crude spot prices shows the same breach of the price cap.

Why is the price of Urals rising? Because the price of global benchmark Brent Crude is also rising.

It is no coincidence that when Urals Crude closed at $61.28/bbl on January 22, Brent Crude closed at $88.66/bbl, it’s highest level since November 15, 2022.

Yet even with the price cap being breached, the discount spread between Brent and Urals illustrates the degree to which the cap has been influential. While Brent Crude last was above $88/Bbl was before November 16, the last time Urals Crude was above the price cap of $60 was the day before the cap was imposed (December 5, 2022). The cap has helped push the price of Urals crude down farther (and faster) than Brent crude, widening the discount (and, by extension, reducing Russian oil revenues).

As 2023 unfolds, the Kremlin anticipates losing even more oil revenue from the EU sanction.

In its government budget, set out in December, the Kremlin predicted that its oil and gas revenues will fall by 23 percent this year. But Alexandra Prokopenko, an independent analyst and former Moscow central bank official, called that figure “very optimistic.” Her own estimate is that those revenues will fall by about a third.

Even a 1/4 drop in oil revenue would be significant, and would put a severe strain on Russia’s economy, increasing Russia’s budget deficit (for 2022 the budget deficit was 2.3% of GDP).

Whether that forecast includes the upcoming EU ban on Russian refined oil products is not certain, as Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov rang in the new year crowing about Russia’s record oil revenues.

He [Siluanov] noted that in 2022 the plan for budget revenues was surpassed. "Total revenue amounted to around 28 trillion rubles, which is 2.8 trillion rubles higher than we originally planned. This was achieved thanks to oil and gas revenues, higher energy prices, and growth of non-oil and gas revenues, including due to the increase in VAT due to growing demand over certain periods last year," the minister said.

The next sanctions step, however, might put a dent in Siluanov’s rosy perspective. Beginning February 5, the EU is set to not only ban imports of Russian refined oil products, but will also extend the price cap mechanism to shipments of those same refined oil products.

The campaign by western nations to defund the Kremlin and force President Vladimir Putin to abandon his war in Ukraine is reaching a delicate phase. From Feb. 5, the European Union will join the UK and the US in banning seaborne imports of Russian diesel and other oil products. The measure, coupled with a price cap on Russian fuel exports, is designed to blow a sizable hole in Moscow’s energy revenues. The flip side: If European buyers are unable to find alternative supplies, the sanctions risk heaping new costs on diesel-reliant industries such as farming and road haulage and make it harder for governments to rein in inflation.

The sanctions on refined oil products could prove to be more impactful than the crude oil sanctions, as it is by no means certain Russia will be as successful in finding replacement customers for products such as diesel fuel as it has been in diverting crude shipments from Europe to India and China.

Asia is thirsty for crude. India and China both import huge volumes for their massive refining systems. The two nations took about 14.5 million barrels a day in 2021, and that figure almost certainly increased last year. By contrast, they brought in just 3 million barrels a day of refined products from overseas.

But those huge systems mean that a ready market for Russian refined products outside Europe simply doesn’t exist in the way it did for crude. Many of the newly built plants were designed to maximize the production of diesel, the very fuel for which Russia needs new buyers.

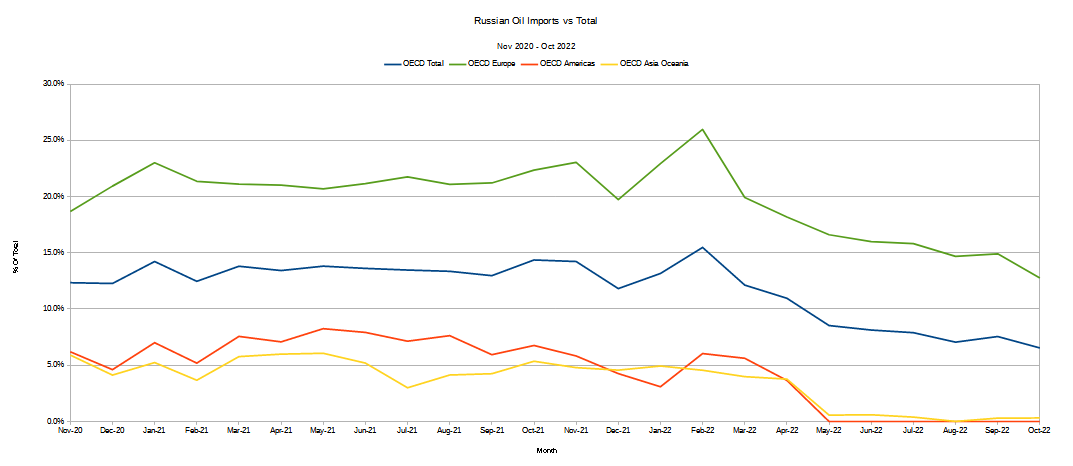

Moreover, while China and India are quite happy to buy Russian oil at steep discounts (and thus have considerable incentive to buy crude below the $60/Bbl price cap), the OECD countries in particular have been quite willing to dispense with Russian oil, as most Asian OECD nations have already largely jettisoned Russian oil as a percentage of their total oil imports.

If Europe succeeds in weaning itself off Russian oil and refined oil products, Russian oil shipments to a wide range of countries including many outside Europe or the Americas will drop to zero—lack of customers willing to buy will always do more to reduce Russian oil revenues than a price cap, as lack of buyers means the revenue trends towards $0/Bbl, not $60/Bbl.

Yet despite the pressures Europe is able (and about) bring on Russian oil revenues, the price cap itself is still facing a severe test, as the price of Brent crude is expected to continue to rise.

Oil markets may face headwinds in 2023 as fresh Western sanctions and a price cap on Russian oil come into effect, leading to an output squeeze in global supplies and putting upward pressure on oil prices.

Demand from China is expected to pick up as zero-COVID restrictions ease, adding to the tightness in energy markets.

Using the spot prices quoted at Trading Economics, the current discount on Urals Crude is $27.24/Bbl against the price of Brent. Because the data is publicly available, it is the pricing platform I use for most comparisons. However, other sources, such as price reporting agency Argus, has reported the discount on Urals Crude as high as $42.

The impact of a G7 scheme to cap the price of Russian oil at $60 per barrel is still unclear, but there are initial signs that traders in nonparticipating nations like China are using the measure to barter for greater discounts. Russia's Urals grade crude is trading at $37.90 a barrel, according to price reporting agency Argus, while benchmark Brent crude price is just over $80 a barrel.

Regardless of what the actual discount is, however, one pattern holds: As Brent goes up in price, Urals goes up in price.

As Urals goes up in price, it eventually must bump into that cap of $60/Bbl. If the cap holds, the price for Urals will not rise above $60/Bbl.

What makes that admittedly obvious reality relevant is that the price of Brent is expected to rise significantly.

Also, with global supplies expected to get squeezed, crude prices will likely soar past $100 a barrel next year, according to Saxo Bank’s Ole Hansen and UBS Global Wealth’s Staunovo.

“The embargo on seaborne crude from now and fuel products from February will likely have a price-supportive impact on markets,” said Hansen, head of commodity strategy at Saxo. The supply disruptions should add to the “expected tightness when demand picks up in China following the current virus surge,” he added.

Those risks raise the likelihood of oil prices topping $100 a barrel, according to Hansen.

“Following a soft first quarter, I see the price of Brent returning to a $90-100 dollar range. What happens later will depend on the strength of an incoming economic slowdown,” he added. UBS’s Staunovo echoed his view.

At a Brent price of $100/Bbl, the price cap can only hold if the discount on Urals is at least $40/Bbl. While the discount was as much as $42/Bbl earlier this month per Argus, the current discount per Trading Economics is $27.24. At $100/Bbl for Brent Crude, a discount of $27.24 on Urals puts the Urals price at $72.76—well above the price cap.

If Brent rises to, say, $110/Bbl, the Argus-reported discount of $42.10 puts Urals Crude at $67.90—well above the price cap.

How high will the price of Brent go? That is as yet indeterminate. Certainly the signs of economic life we are seeing in a China attempting to re-open from Zero COVID suggest that global oil demand will increase, and so the price of Brent Crude will increase, which in turn will cause the price of Urals Crude to increase.

How much of a resurgence we see in China will likely impact how much increased global oil demand we see, and how much of an increase in Brent crude we will see.

Yet China’s efforts to have such a resurgence may also motivate them to negotiate to keep the price of Brent under the $60/Bbl price cap, which will entail widening the discount at some point (depending on how high the Brent price moves).

This much seems likely: The EU/G7 price cap on Russian oil is going to come under increasing pressure in the coming weeks and months. How long the price cap holds up will tell the tale regarding economic leverage between the EU and Russia.

Yet even if the price cap does not hold, Russia is still likely to find itself with Urals trading at steep discounts to Brent, as it was doing that already before the price cap. Russia is still faced with reduced oil revenues with or without the price cap, and the only operative question is how much of a reduction will they have.

This much remains unknown: Which side is going to come out on top, Russia or the EU.

2023 is going to be an interesting year for oil!

You discuss the market for Russian oil and refined products being restricted if the price cap holds firm (ie if Brent doesn't rise too much). What's to stop these being laundered through China, India etc at a markup to embargo obeying countries?

As for Europe and the other OECD nations weaning themselves from Russian oil, this can only happen if they find replacements from other oil producers (the green divestment fantasy will not happen). This would only occur by these nations driving up the price of their oil purchases which must drive up Brent and cause shortfalls for other nations. These poorer nations will then buy Russian oil and refined products (directly or laundered) to supply their needs at affordable prices. The only scenario I can see for demand for Russia products collapsing is a worldwide recession crushing general demand.