It should go without saying that the sector of the US economy most directly impacted by the Federal Reserve’s interest rate machinations is banking and finance. The Federal Reserve notionally sets interest rates and then banks make the loans.

Without loans in all their many forms, from regular loans to credit lines to mortgages to corporate debt, modern economies could not function (whether that’s good or bad I leave for the reader to decide). As a result, if the Federal Reserve’s interest rate manipulations hurt banks, we should be concerned.

There are signs that not all is not well with America’s banks.

On the surface, the Fed’s interest rate hikes are a blessing to banks, as it increases the amount of interest they can charge on loans. Certainly, according to the FDIC’s quarterly income data, banks are reaping an interest income windfall from the Fed’s rate hikes, as both interest and total income has risen since the Fed began hiking rates.

However, while banks are earning more money from the loans they generate, more of the loans they generate are starting to fall into arrears.

Real estate loans have soured slightly since the second quarter.

After enjoying a period of declining loans in arrears status, beginning in the second quarter real estate loans began to fall more often into arrears, becoming over 30 days past due.

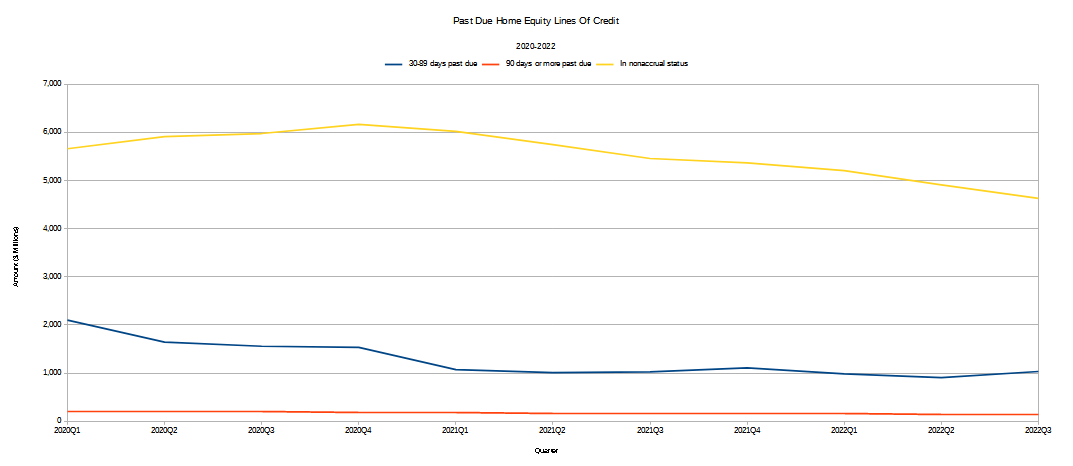

Home equity loans are showing a similar uptick of late.

Commercial and industrial loans began to deteriorate as early as the fourth quarter of 2021.

While the increase in arrears status among real estate loans is an extremely small shift, it is nevertheless concerning that the increases coincide with the Fed’s rate hikes, making it a trend to be watched.

The deterioration of commercial and industrial loans is certainly cause for concern, given its much larger magnitude (and the reality of network effects arising from business failures, which loan deterioration indicates is a pending problem).

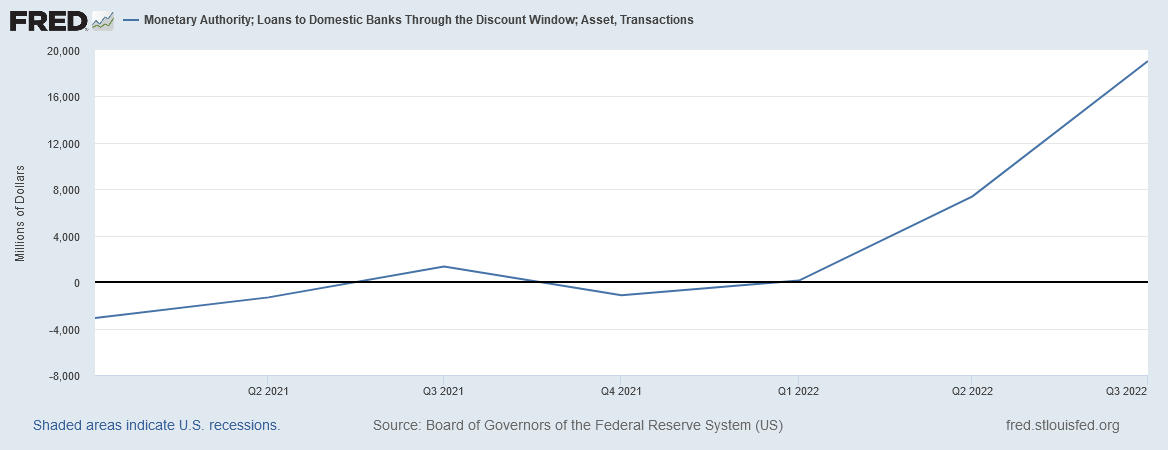

There is some indication that loan quality problems are causing liquidity stresses for at least some banks, as there has been a marked increase in the use of the Fed’s discount window in recent quarters.

This has caught the attention of some on Wall Street, although most are not terribly alarmed at it—yet.

For now, worries are low. Some even believe rising usage of what the Fed calls the Discount Window could show the waning of persistent stigmas that have long kept banks away from an easily accessible source of short-term loans.

That said, if borrowing continues to rise, it could signal trouble at a time when many are already worried very aggressive Fed rate rises might break something in the financial system. Rising usage could also mean financial sector liquidity is running short, which could cause the Fed to slow or bring an early stop to efforts to shrink the size of its balance sheet.

Given that the Fed’s discount window is where banks go to borrow when they cannot borrow from anywhere else, a rise in discount window transactions could signal a coming wave of bank failures, as it indicates a growing number of banks unable to address short-term liquidity concern.

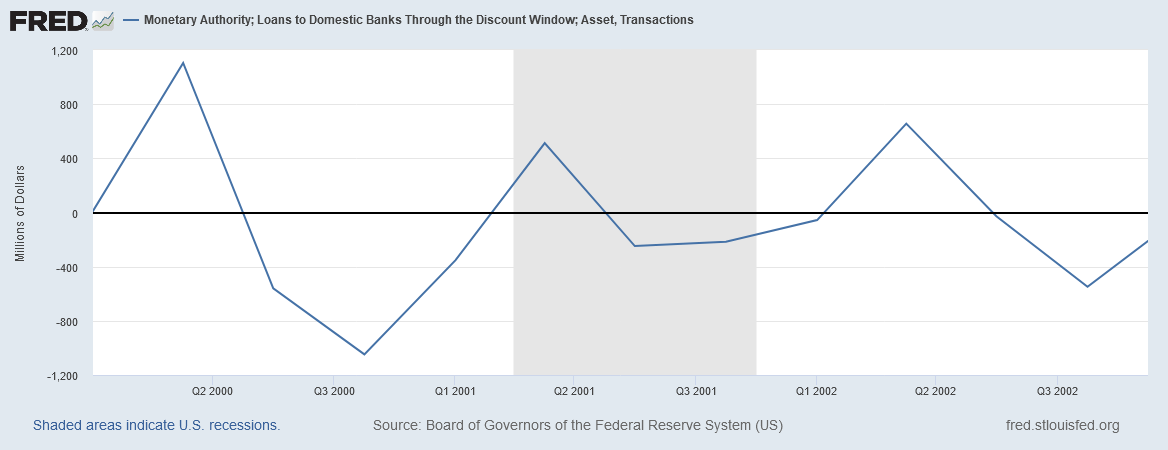

While discount window usage can be a leading indicator of banking stress, one should not read too much into use of the discount window itself. Although discount window usage has historically risen during recessions and other periods of economic turmoil, the timing of that usage relative to the onset of both the 2008-2009 and 2001 recessions makes it a problematic signal at best.

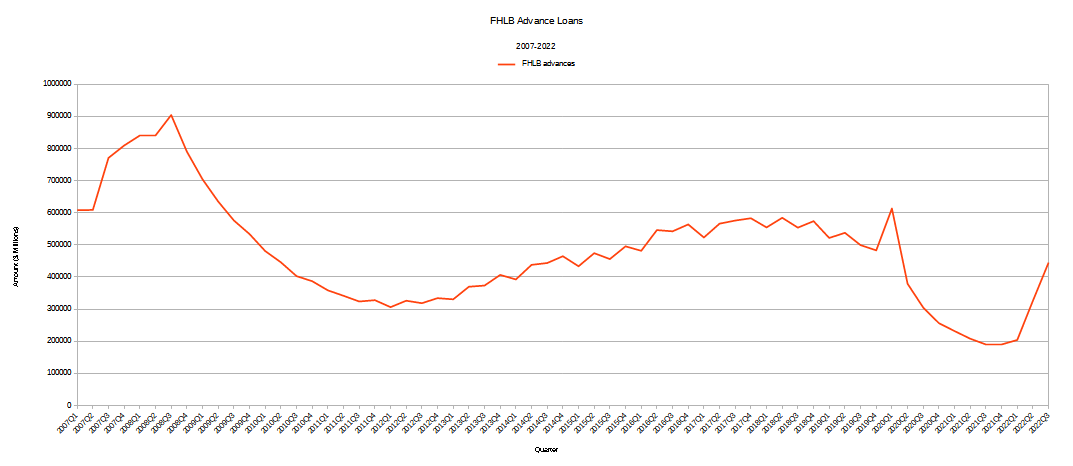

However, the discount window is not the only source of “emergency” funding available to financial institutions. The Federal Home Loan Banks also make short term loans to member institutions provided they can post collateral of adequate quality (e.g., mortgages or other secured loans).

The Federal Home Loan Banks provide funding to members such as commercial banks via advances. These tend to be short-term loans secured by mortgages or other collateral, and banks had little need for them when they were flush with cash.

Recent quarters have seen a marked increase in the issuance of FHLB advance loans, according to FDIC data.

Nor is the increase merely a rounding error. After a brief surge during the 2020 pandemic-induced recession, FHLB advance loans have been declining until the fourth quarter of last year, after which they have more than doubled.

Unlike discount window usage, FHLB advance loans do line up very well with prior recessions, making this a clear signal of banking distress.

Even Wall Street attributes the recent rise in FHLB advance loans to the Fed’s interest rate hikes.

But advances have returned to pre-pandemic levels, totaling $655 billion as of Sept. 30, up 86% from the end of 2021, data from the Home Loan Banks' Office of Finance show. Driving the leap: declining deposit balances, loan growth and the effects of higher Fed rates. Of note, commercial banks were the largest segment of borrowers, with 55% of the total principal amount of advances outstanding at the end of the third quarter.

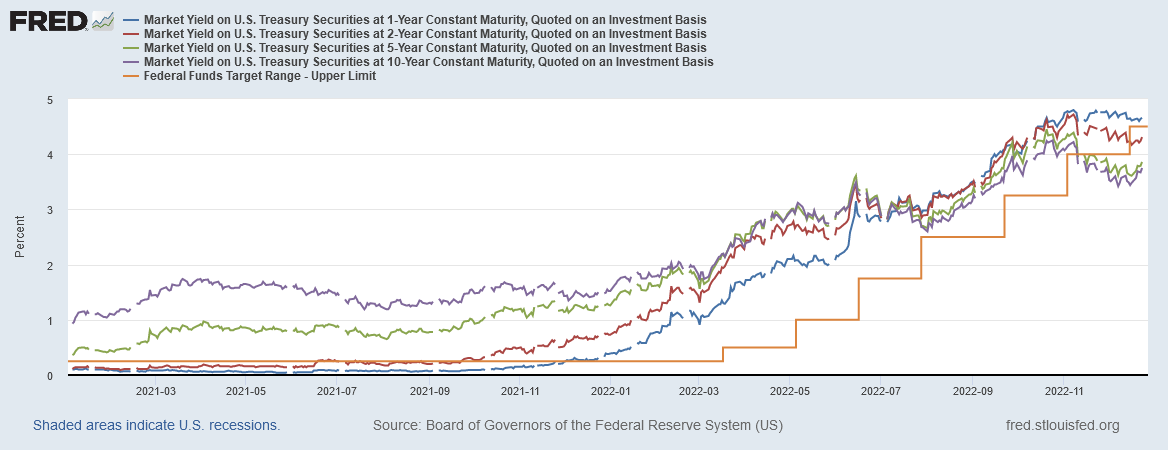

Intriguingly, these signals come even as the Fed’s efforts to raise interest rates have largely stalled out, with the last two Federal Funds rate increases failing to push benchmark Treasury yields higher. In fact Treasury yields have slipped below the Federal Funds rate in recent weeks.

Despite the market’s reluctance to see interest rates rise further, at least some banks are facing funding and reserve shortfalls and are needing emergency assistance to cover their needs.

However, it is far from certain that interest increases alone explain banks’ funding dilemmas. If the New York Federal Reserve’s assessment that consumer price inflation in this country is at the present time 60% demand side (i.e., monetary) factors and 40% supply side factors, the Fed’s rate hikes may very well have eliminated all the consumer price inflation they are able to eliminate, with the rest being the result of supply chain dislocations and other economic imbalances not related to consumer demand.

With 60% of November’s consumer price inflation figure roughly matching the 10 year Treasury yield and coming in below the current Federal Funds rate, the possibility the Federal Reserve’s rate increases have accomplished all they can accomplish is one extrapolation of the New York Fed’s research, and further rate hikes beyond this point would simply be gratuitous economic damage.

If this is the case, then continued rises in FHLB advance loans are a definite indicator of growing weakness among US banks.

To be clear, signals such as rising FHLB advance loans and rising discount window usage are not signals of imminent banking system collapse. They are not signs of sudden instability within the nation’s financial markets.

The warnings we are seeing with rising FHLB advance loans and discount window usage are of a structural weakness within the banking system. A growing number of banks potentially are facing increasing difficulties in meeting funding and reserve requirements, and are increasingly resorting to emergency measures to cover their shortfalls. Slowly, and almost silently, the nation’s banking system appears to be growing more and more fragile.

Which will make the next liquidity shock, the next financial crisis, that much worse, as banks will be less able to absorb the impact.

Very much agree. My instincts tell me that this is not just a USA occurrence.

Have you noticed similar signals globally?

These are technical details, but all facts matter. Since March of 2020, the required reserve rate is zero for all financial institutions. The issue is mainly cash liquidity (definitely a legitimate concern), not required reserves. Also, the Fed has been working hard for over a decade to remove the “lender of last resort” stigma from the discount window. While not significant in the grand scheme of things, the annual crop lending cycle for most ag banks peaks in August-October, so borrowing data (FHLB and FRB) on the 9/30 Call Reports tends to be higher than in other quarters. I’ve also seen banks with excess capital enter into leverage strategies of matched or mismatched duration over the last four months (funded by wholesale borrowings) to acquire bonds at expected cyclical high yields.