Jay Powell Is Lost In The Weeds

What Happens When His Rate Hikes Don't Bring Down Inflation?

Fed Chair Jay Powell continues to insist that not only is the US not in a recession (we are), but that the Fed’s program of interest rate hikes will bring down inflation without pushing the US into a recession (it already has). In a Q&A session at the Cato Institute on Thursday, Powell compared the current situation to the Volcker era, suggesting that Volcker’s “chemotherapy” would not be needed this time around.

“We think we can avoid the very high social costs that Paul Volcker and the Fed had to bring into play to get inflation back down,” Powell said in an interview at the Cato Institute, referring to the Fed chair in the early 1980s who sent short-term borrowing rates to roughly 19% to throttle punishingly high inflation.

Powell essentially reiterated the talking points he laid out two weeks ago at Jackson Hole, emphasizing his determination to get inflation down, no matter what.

His determination would sound so much more credible if it were actually grounded in some reality.

His cluelessness would sound less scary if it weren’t actually shared by most of his central bank peers, who are following the Fed script of swift interest rate hikes.

On Thursday, the European Central Bank increased its key rate by three-quarters of a point, the largest in its relatively short history, as Europe also struggles with record-high inflation and a stumbling economy.

Central banks around the world are scrambling to keep up with rising prices. The Bank of Canada on Wednesday lifted rates by 0.75 percentage point and earlier this week the Reserve Bank of Australia implemented a half-point increase.

This growing symphony of interest rate hikes presumes that high interest rates will corral inflation, but what if that’s not what is going to happen? What if something other than excess money supply is driving the current inflation?

Interest Rates And Inflation

The governing premise behind the Fed’s rate hike policies is that increases in general interest rates will head off further increases in inflation. Necessarily, this requires there be a good correlation between interest rates and the rate of inflation. Thus the question must be raised: what is the evidence of correlation between interest rates and inflation?

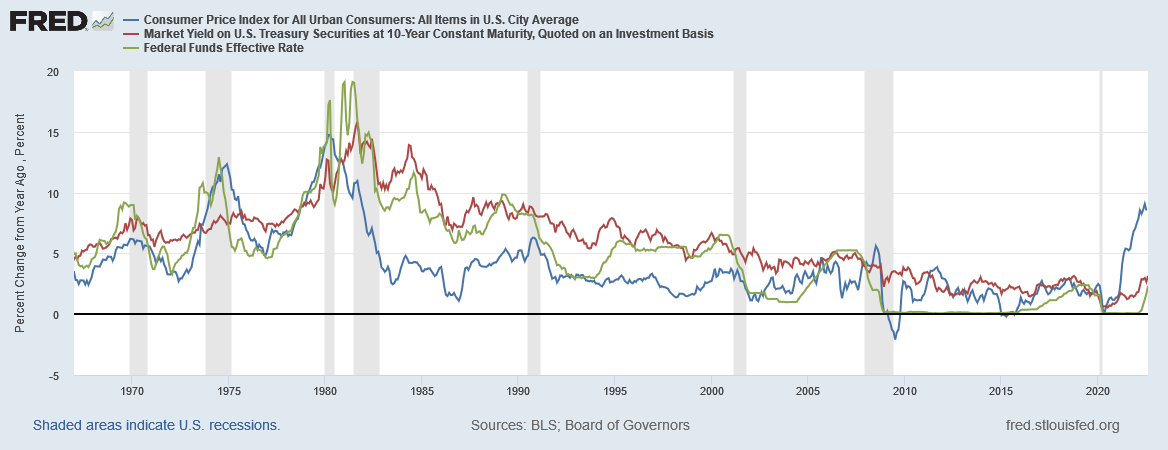

At first glance, when we look at the rise and fall of both interest rates and inflation in the US since 1967, there does appear to be a broad pattern of correlation:

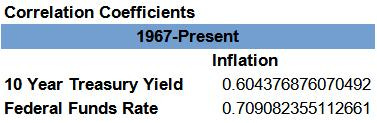

In particular, we can see that the high interest rates of the early 1980s correspond to the lessening of inflation during that period, although there is clearly room for other factors to influence inflation. However, we should not leap to the conclusion that interest rates alone drive inflation. A calculation of the coefficient of correlation1 between inflation and both the 10 Year Treasury yield and the federal funds rate shows a more moderate connection than is often expressed by the media.

Thus while we should not ignore the inflationary consequences of both high and low interest rates, we should never view them in isolation. The correlations are simply not strong enough to warrant such exclusive treatment—something Jay Powell has overlooked repeatedly in his public comments.

More importantly, the relationship between interest rates and inflation is not at all consistent. When we view the correlations across ten year intervals, we see them fluctuate significantly.

Analyzed by decade, the relationship between inflation and the 10 Year Treasury yield was strongest between 1967 and 1976 (the period in which inflation and stagflation first took hold), then dropped dramatically from 1977 to 1986, while the relationship between the federal funds rate has been weakening over time and from 2017 onward shows a negative correlation (interest rate falls while inflation rises).

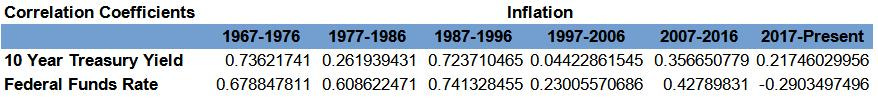

Covariance2 is the statistical complement to correlation, and describes the strength of the correlation in question. When we view the covariance metrics of interest rates to inflation, we see a similar fluctuation in play.

Statistically speaking, the power of interest rates to impact inflation is quite a bit weaker now than it was during the Volcker era and before. No matter what we may believe to be true about interest rates and inflation, the historical data shows that Jay Powell is deploying a far weaker and less impactful weapon against inflation than Paul Volcker had, and even a weaker weapon than Volcker’s predecessor as Federal Reserve Chair Arthur Burns had.

At a minimum, the Fed’s confidence in the success of their inflation fighting strategy is greatly overstated and not at all supported by the evidence.

Money Supply And Inflation

In 1963, Milton Friedman famously observed that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”3, and that monetarist view has been a guiding force in Fed policy ever since. Friedman's deeply held view was that the driving force behind inflation is always the rise and fall of the supply of money in an economy.

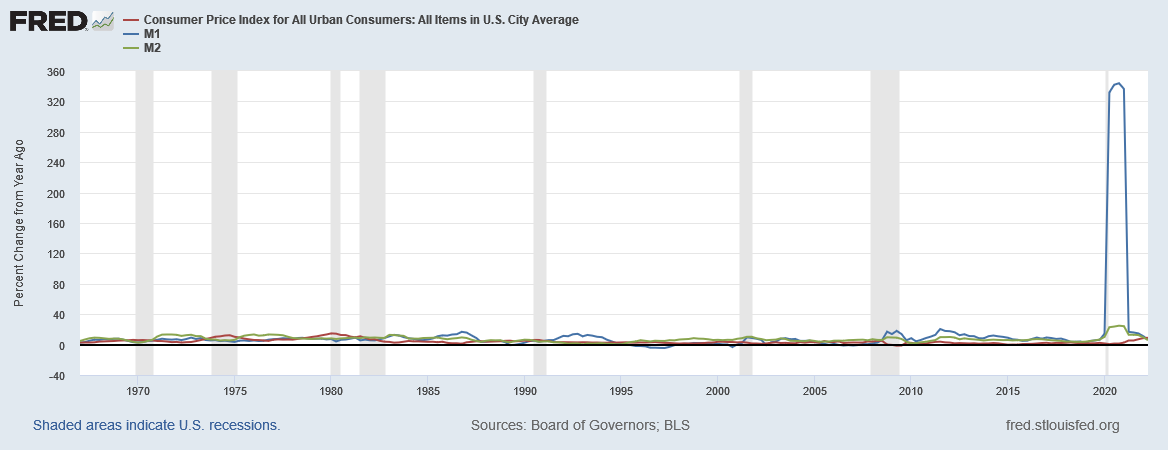

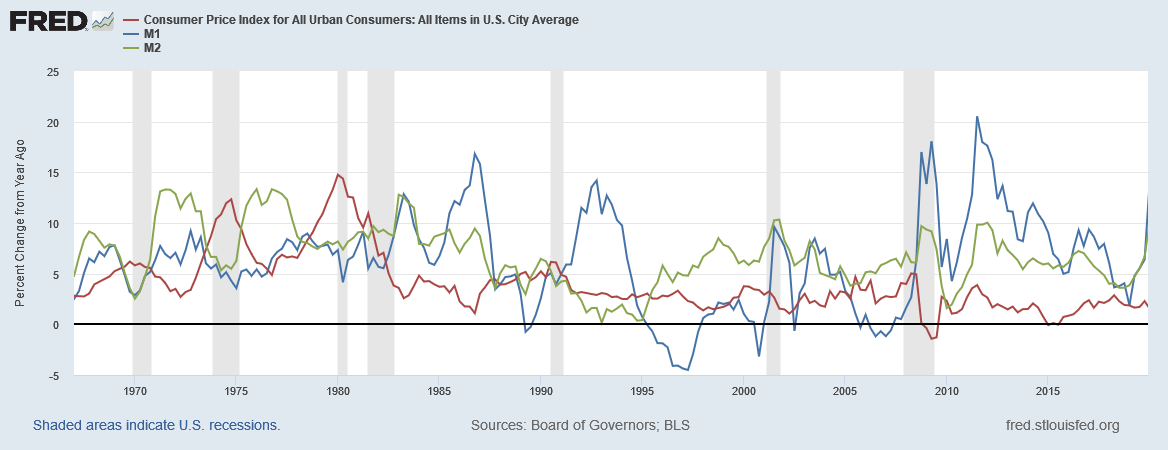

Accordingly, we should see a correlation between inflation and the growth of the money supply in the US when we compare the two from 1967 to the present.

For visual clarity, this is the relationship from 1967 to 2019, omitting the huge money supply spike of 2020

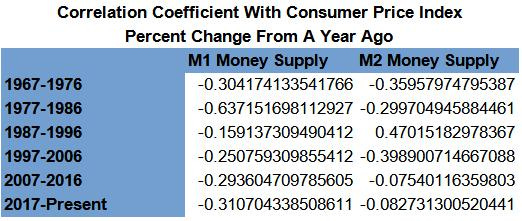

Do we see a correlation? Certainly not the one we might expect. Viewed by decade, the correlation coefficient between the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index and the percentage change in the M1 money supply is actually negative.

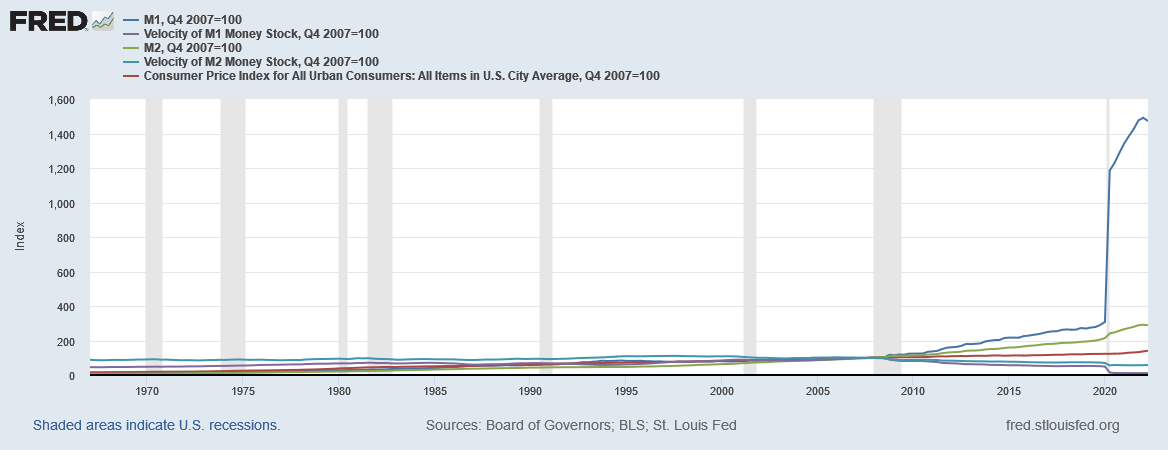

However, when we reduce CPI, M1 and M2 money supply, and M1 and M2 money velocity to a common baseline index, we see that there is unquestionably a long-term consistency among these metrics—with an interesting twist.

Note that whatever the relationship between money supply and consumer price inflation might be, it fractures during the 2007-2009 recession.

Nor is this purely an anomaly of statistics. Economists Paul De Grauwe and Magdalena Polan analyzed inflation and money growth in 2001, only to conclude that, in low-inflation countries, the relationship between money growth and inflation was weak4.

Using a sample of about 160 countries over the last thirty years we test for the quantity theory relationship between money and inflation. When analysing the full sample of countries we find a strong positive relation between the long-run inflation and money growth rate. The relation is not, however, proportional. The strong link between inflation and money growth is almost wholly due to the presence of high (or hyper-) inflation countries in the sample. The relationship between inflation and money growth for low inflation countries (on average less than 10% per annum over the last 30 years) is weak. We find that the long-run average inflation and country-specific factors have a significant influence on the strength of the relationship. We also confirm that money growth and output growth are orthogonal in the long-run; i.e. higher growth rates of money do not lead to higher growth rates of output.

While Friedman’s assessment of inflation and money supply holds true over the long-term, the data does not support a thesis that tight regulation of money growth will restrain inflation. Over shorter time frames, the influence of other factors—i.e., the many exogenous supply shocks the world economy has endured since 2020—are as influential and even more influential.

The Wrong Weapon Aimed At The Wrong Target?

If the Federal Reserve’s own data does not support the Federal Reserve’s thesis that raising interest rates will reduce inflation, just as it did for Paul Volcker, why is Jay Powell—who should be fully conversant with this data if he’s at all doing his job—advancing that thesis? (An interesting corollary question: did Volcker’s interest rate hikes actually cause inflation to subside, or was he merely a beneficiary of good timing?)

As a matter of simple common sense, interest rate hikes in response to exogenous supply shocks such as the Pandemic Panic lockdowns, China’s Zero COVID lunacy, or Russia’s illegal war with Ukraine seems absurd. Raising American interest rates is not going to alter China’s COVID policy, nor will it restore the flow of Russian and Ukrainian resources to the world.

Yet the data does not even support a contention that through job loss and demand destruction, higher interest rates will drag inflation down regardless of the exogenous shocks. Jay Powell is running a very real risk that interest rate rises may choke off real economic growth without generating much positive benefit for consumers.

Jay Powell is pointing the wrong weapon at the wrong target if he means to control consumer price inflation within the United States. He may get lucky, a la Paul Volcker, and inflation will drop enough for him to claim credit for its reduction, but it is also possible, and may become more probable, that his luck will not hold, and his rate hikes will produce job loss and labor demand destruction without having the desired impact on consumer price inflation.

That Jay Powell—and, for that matter, the rest of the brain trust at the top of the Federal Reserve—is blissfully unaware of what the data shows is by far the most disturbing aspect of the Fed’s stance on inflation. Jay Powell might be ignorant of the data, but as Federal Reserve Chairman he has an obligation not to be.

The source data for all statistical calculations is the Federal Reserve Economic Data system (FRED). The calculations themselves were performed using LibreOffice Calc 7.3.2.2

Weisstein, Eric W. "Covariance." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/Covariance.html

Friedman, M. “Inflation: Causes and Consequences. First Lecture.” Dollars and Deficits, Prentice Hall, 1968, pp. 21–46. Retrieved online from https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/271018/full

De Grauwe, Paul and Polan, Magdalena, Is Inflation Always and Everywhere a Monetary Phenomenon?. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=290304 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.290304

I'm not sure it makes sense to look at correlation coefficients when, if excessive M2 drives inflation, there will be a lag between them.

Just eyeballing it, until 1980 there is about a 5-year lag between the shape of M2 and inflation, and as time goes by the lag becomes shorter and shorter. It would be interesting to do a correlation with a gradually-decreasing lag time. Maybe it could be done the other way around, to calculate the lag-time function that maximizes the correlation between M2 and inflation.

It does make some intuitive sense that increasing computerization and internet usage would shorten lag times.