It surely has to be a great frustration to Democrats that the world does not stop turning merely because they refuse to reopen the federal government.

For those of us operating in the real world, that is a source of much relief—because the consequences of the financial world “stopping” are not at all good.

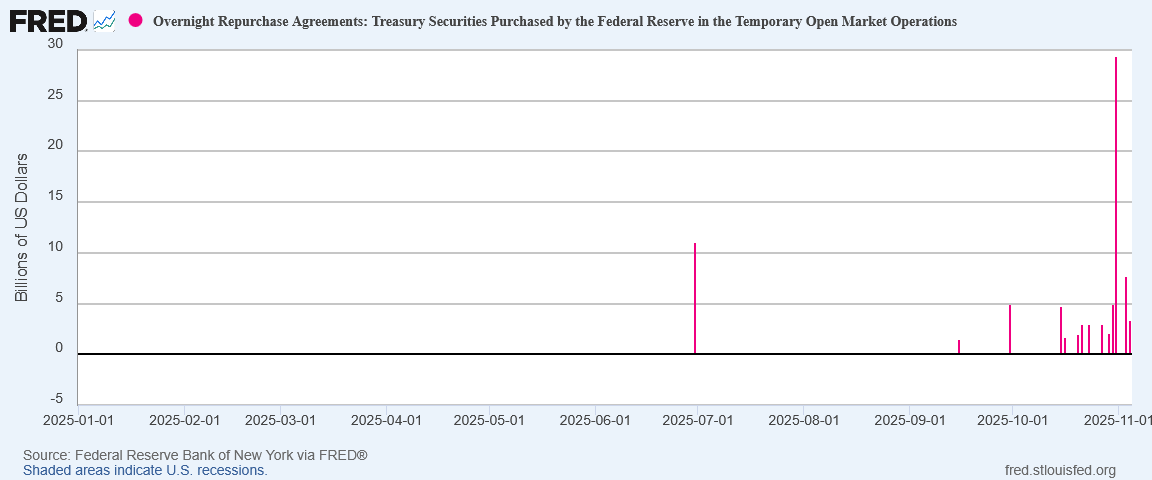

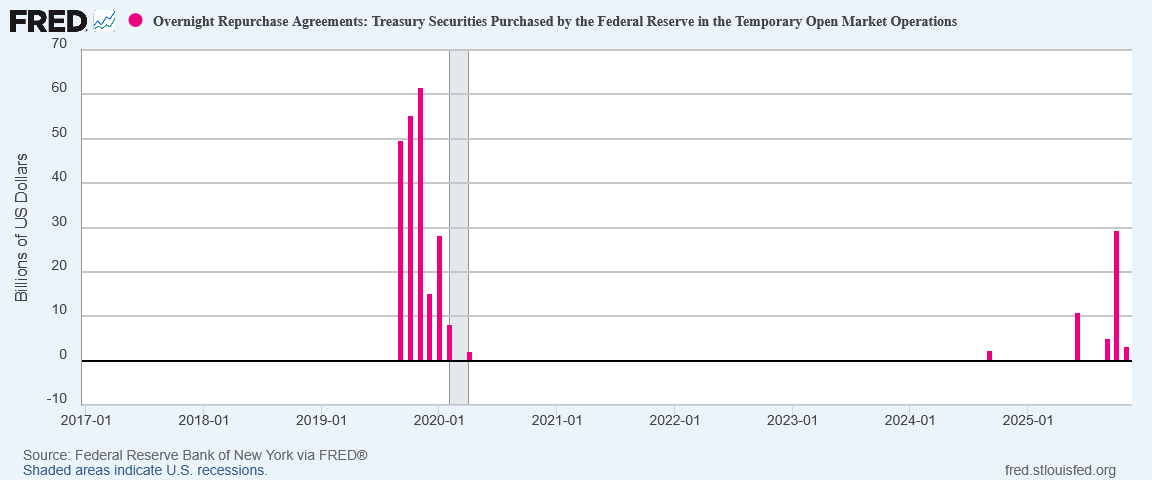

While most of corporate media (and, for that matter, alternative media) has been focused on the shutdown and the hypocritical politicking over SNAP funding from both Democrats and Republicans, the financial world gave a small warning of what “stopping” might look like late last week, when overnight repurchase activity surged, after having been fairly quiet for most of the year.

The end of any month is always a time of peak cash consumption by the banking industry, and October was no different—except the demand for cash was many times higher than it had been all year.

Is the US banking industry facing another mini-liquidity crisis such as the 2023 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank?

How is that happening at a time when the Federal Reserve is trimming the federal funds rate, albeit grudgingly?

We should not that it is by no means certain that a liquidity crisis or even a banking crisis is on the horizon. However, it is also not certain that a liquidity or banking crisis is not bearing down on the economy.

What is certain? That a weak economy is putting the banking sector under its own forms of stress.

One important point to note is that the overnight repo surge last week was not even close to being the largest such surge in recent memory. That honor occurred pre-COVID.

While the overnight repurchase market always surges when there is a broad need for quick cash, we should also note that one of the signature failures of the Fed under Jerome “Too Late” Powell has been to make the overnight repo a preferred funding mechanism.

Borrowers use Treasuries or other debt securities as collateral, agreeing to repurchase them in the future at a pre-determined price. A typical repo transaction involves a dealer borrowing cash from a money market fund and lending the cash to a client such as a hedge fund.

Repo demand has always been high because these transactions are more efficient in mobilizing cheaper and deeper funding for financial intermediaries and borrowers as they reduce dependence on commercial banks. Its volume has surged even higher as trading strategies that depend on them have become more popular, while primary dealers are reluctant to boost capital reserves required to handle more trades.

Simply put, when banks need cash, they turn to the overnight repo marketplace.

As we saw during the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023, however, when cash piles up in any one place within the financial system, funding balances—what we mean when we use the rather anodyne term “liquidity”—become imperiled. In 2023 that resulted in Silvergate, SVB, and First Republic all having inadequate access to cash at a crucial juncture, precipitating a final crisis that brought each institution crashing down.

Is a systemic imbalance building up? The signs are certainly there.

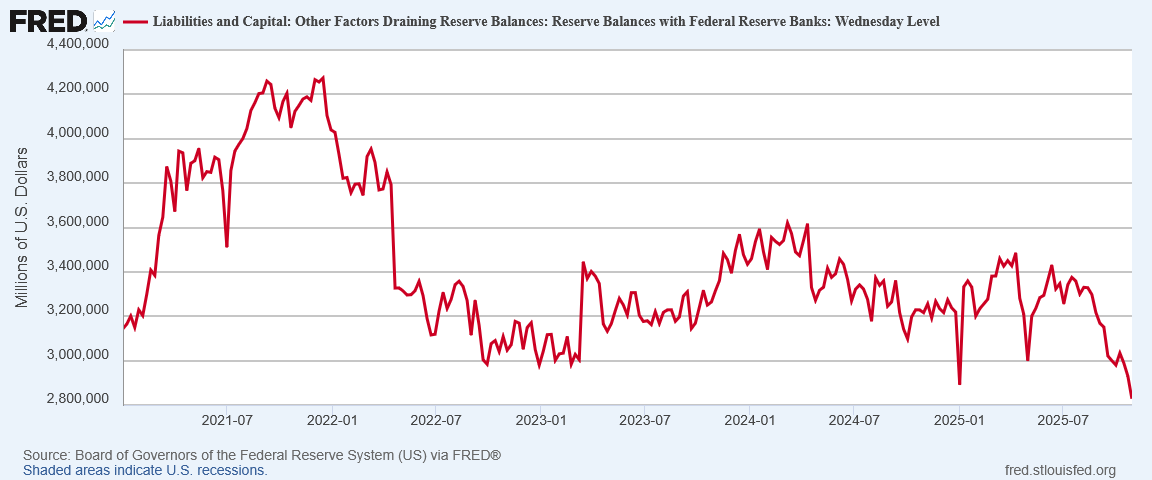

The leading indicator of this is that reserve balances with Federal Reserve banks have recently dropped to the lowest level since the start of the Biden Administration.

At the same time, non-reserve balances have spiked.

Any rapid shift of this sort means that cash is accumulating in one part of the financial system and not another.

Correlating with the shift from reserve to non reserve balances has been an increase in Treasury yields—an increase which cuts against the grain of last week’s federal funds rate cut.

This is a warning sign because when yields rise, the potential for imbalances within the system increases. As I touched on when the Fed began boosting the federal funds rate in 2022, this was always the Achilles Heel of the Fed’s rate hike strategy.

The concern within financial markets today is that, as the Fed tightens the money supply to control inflation, there will not be enough dollars at crucial points to satisfy dollar liquidity demands. In other words, there is a perceived risk on Wall Street that, as the Fed reduces the overall supply of money, that there will not be sufficient dollars available to participants in various asset transactions to allow those transactions to be completed.

The question is not whether there is enough money sloshing around in the financial system, but whether the money is where it needs to be to service various transactions.

In 2008-2009, during the Great Financial Crisis, the rapid collapse of first the subprime mortgage market and then the derivative markets built on subprime mortgages became a crisis in large part because cash was not where it was needed to unwind the derivative transactions in an orderly fashion, causing a cascade of credit defaults.

In 2023, SVB and First Republic lacked access to enough cash on hand to keep depositors calm, triggering the kryptonite of every banking institution, the bank run.

Lack of liquidity does not mean lack of cash. Rather, it means the financial system does not have the cash at the key nexus points where it needs cash most. When this imbalance becomes systemic, the impacts, as we have seen before, become quite large.

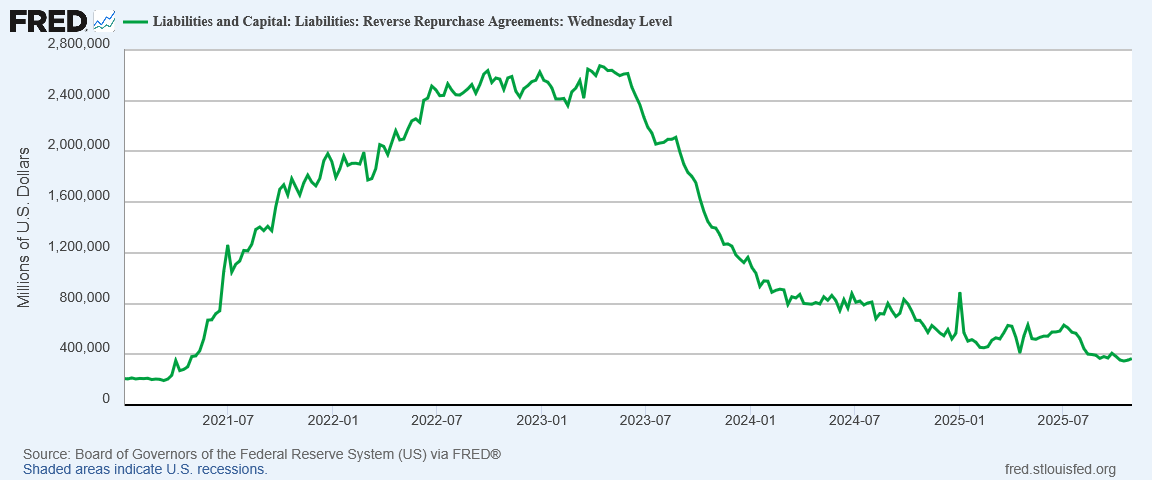

As reserve balances have dropped and non-reserve balances have increased, one of the important buffer mechanisms in the system—reverse repurchases—has also dropped to a significantly low level.

Reverse repurchases had soared during the hyperinflation cycle of 2022, an indication of how much cash the Fed wanted to remove from the financial system to choke off hyperinflation. Reverse repurchases peaked at about the same time as the hyperinflation cycle peaked in mid-2022. They have been declining ever since early 2023.

These shifts in money balances in the financial system are occurring in part because lending—the primary reason the financial system exists—has been showing signs of stalling out.

Commercial lending in particular peaked at the same time as reverse repurchases began to decline, and then nosedived to start 2025. Thus far, lending has not rebounded, but only stabilized.

And so here we are.

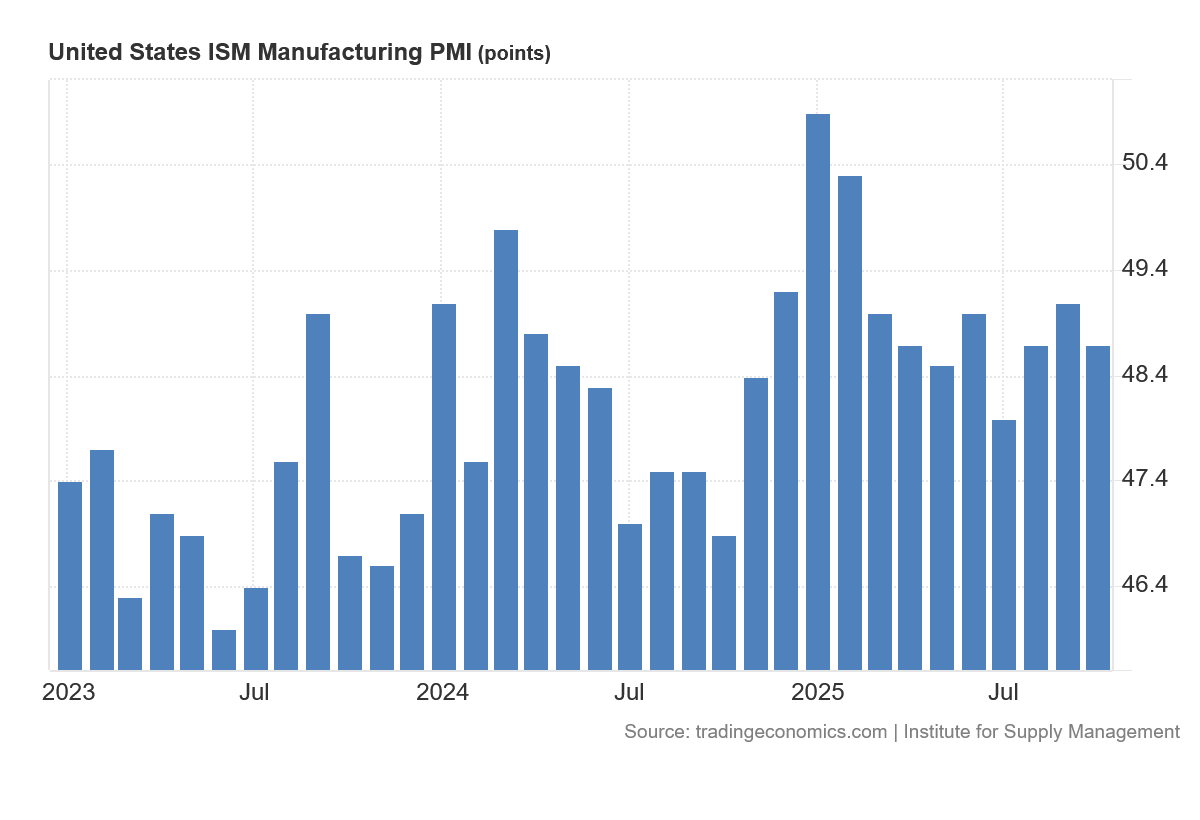

While commercial lending being in decline—the sharp drop to start 2025 was just part of a larger decline since January 2023—plays a role in the evolution of potential funding imbalances, we should also note that lack of commercial lending has undercut manufacturing activity within the US economy. As measured by the Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing Purchaser Manager’s Index (PMI), the manufacturing sector contracted even further last month.

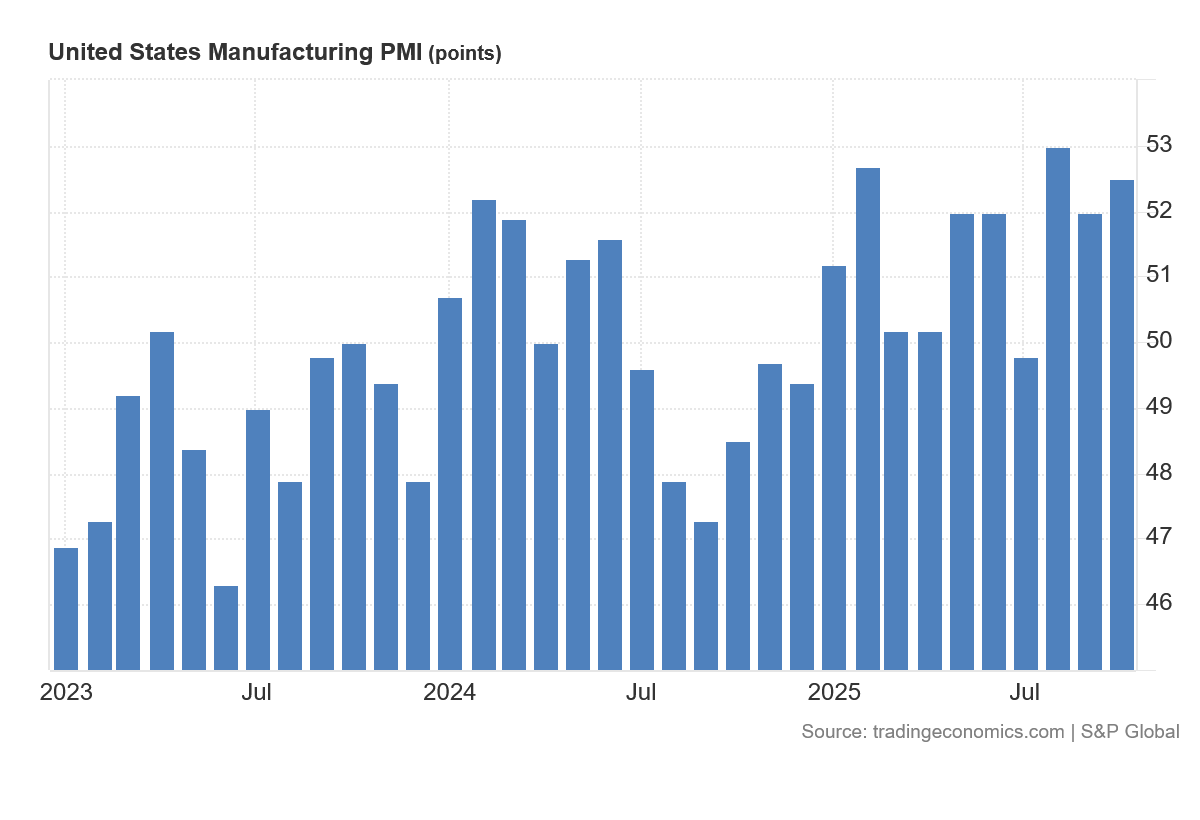

Even the more optimistic S&P Global Manufacturing PMI shows the sector having at best weak growth.

While a lack of robust growth in manufacturing within the US economy does not itself produce either funding imbalances or the buildups which can quickly metastasize into a liquidity crisis, declining commercial lending means manufacturing is not leveraging investment capital to fund any sort of growth.

The same lack of commercial lending which contributes to growing funding imbalances also is a factor in why manufacturing is contracting.

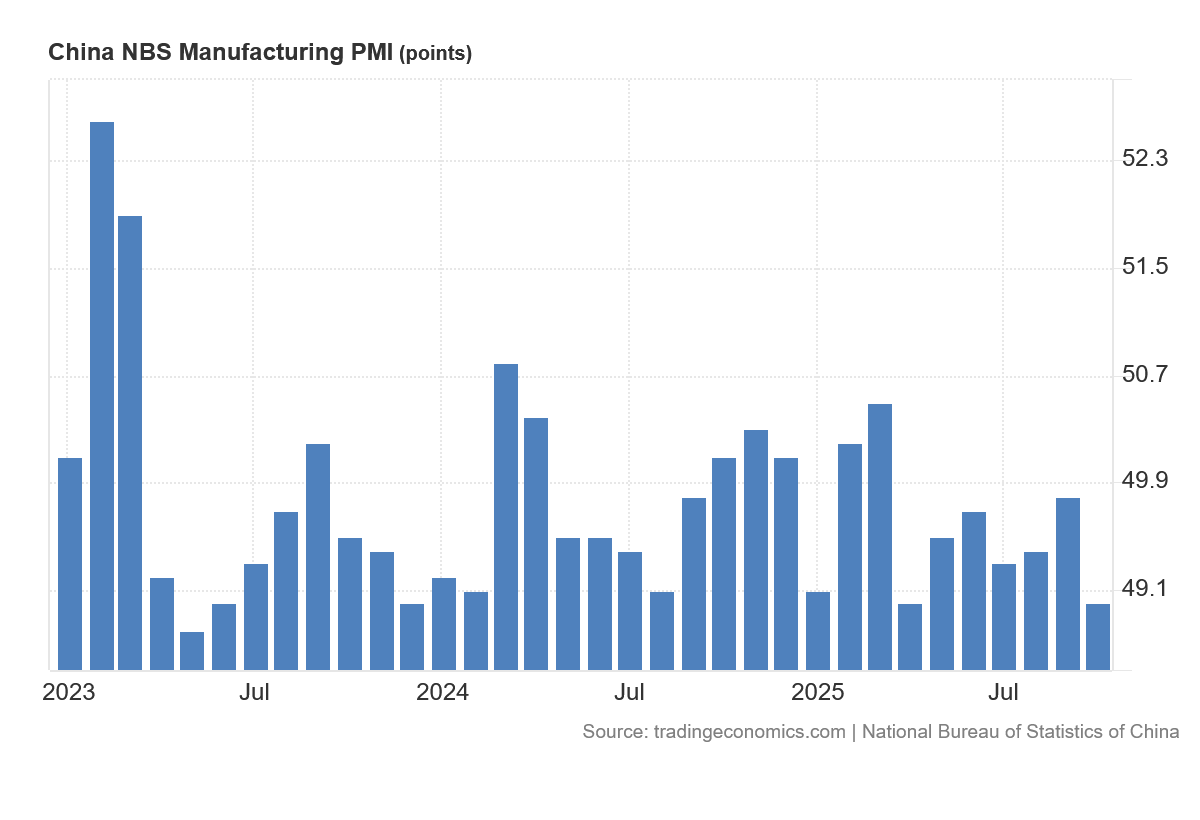

We should note at this point that lack of growth in manufacturing is, at the moment, something of a global phenomenon.

China’s manufacturing sector has been in long-term contraction since early 2023.

The Eurozone has likewise not seen any real expansion in manufacturing since 2023.

Germany especially has seen their manufacturing sector contract over the past two years.

Not only are banks not lending to support US manufacturing, they are not lending to support manufacturing globally.

The typical scenario for a liquidity crisis involves interest rates (yields) rising, curtailing lending activity, leading banks to park cash in ultimately non-strategic points within the financial system. We may be seeing signs that, when interest rates are not reduced from restrictive levels, an atrophy of lending activity can result in the same sub-optimal choices by banks on where to put idle cash.

Earlier in the summer I concluded that the Fed erred by not being more aggressive in reducing the federal funds rate because of rising joblessness in this country.

The concern at that time was lack of job growth particularly within US manufacturing.

That concern still holds true, but to that concern we perhaps should add a concern that a failure to stimulate lending at a crucial time is making the financial system itself more brittle. The financial system has in the aggregate plenty of cash, but stagnating loan growth means that cash is not getting spread around the system.

In any complex system, a lack of activity leads to systemic breakdowns. If we are not physically active, our physical health suffers. If an engine is not run at least some of the time, it can seize up and not run at all.

Financial systems are no different from bodies or engines in this regard. Without fresh lending activity to stir cash flows through the system, cash will accumulate wherever it happens to be—which means at some point it will not be where it is needed. When banks do not lend, or do not lend enough, systemic imbalances arise, giving birth to a liquidity crisis.

The recent surge in overnight repo activity may prove to be a leading indicator that America’s banks are not generating enough lending activity with America’s businesses—and with manufacturing businesses in particular—to ward off the accumulation of systemic cash imbalances, imbalances which will ultimately get resolved through the shock of a liquidity crisis.

The Federal Reserve’s reluctance to trim the federal funds rate is certainly not the only reason for contraction within the manufacturing sector. What is more certain is that, with higher interest rates making business loans proportionally less appealing to businesses, a lack of loan activity quickly translates into a lack of investing activity, which translates into the persistent contraction we are seeing in the PMI data.

Had the Federal Reserve been more willing to trim the federal funds rate aggressively, manufacturing concerns might have been more willing to borrow more to fund future investment and expansion. Commercial lending might be rising and not declining. Systemic imbalances might not be building as a direct consequence.

Had we seen more rate cuts, or larger rate cuts, over the past year, the financial systems within the US economy likely would have lent more, funded more, and moved more cash around as a result, making systemic imbalances less likely.

The recent surge in overnight repo activity may yet prove that “Too Late” Powell is also “Too Little.”

That’s not a comforting thought.

Cutting-edge analysis, Peter - you are once again amongst the first to see the storm clouds bubbling up.

So, the question I have today is: how will the election results affect this banking situation? On the one hand, the financial world already expected New York to elect a far-left disaster, and CA to enact further nuttiness, so there’s little surprise in the election. On the other hand, the ruin coming to NY is now a reality. Will it spark enough concern to push some financial metric over the edge? Any new concerns, Peter?

Stagnant Manufacturing in the West is a long term problem. Machines wear out. We [USA] are not building quality products and I think that mandated health care costs and regulations are partly to blame, but the pay and cushy benefits of public sector employers draw workers away from manufacturing. The market for 'workers' has been skewed towards the collective and away from the private sector and the producers..... A=A.