The collapse of “cryptocurrency bank” Silvergate Capital and the sudden demise of Silicon Valley Bank, the 16th largest bank in the US share one name in common: Jerome Powell.

Silvergate, long touted as “the crypto bank” because of its deep ties to cryptocurrency and cryptocurrency business ventures, on Wednesday, March 8, announced it was winding down operations and would liquidate its remaining assets.

Crypto-focused lender Silvergate said it is winding down operations and will liquidate the bank after being financially pummeled by turmoil in digital assets.

“In light of recent industry and regulatory developments, Silvergate believes that an orderly wind down of Bank operations and a voluntary liquidation of the Bank is the best path forward,” it said in a statement Wednesday.

The bank’s plan includes “full repayment of all deposits,” it said.

Silicon Valley Bank, not at all a “crypto bank”, was seized by banking regulators on March 10 after a bank run triggered its sudden failure.

The U.S. rushed to seize the assets of Silicon Valley Bank on Friday after it experienced a run on the bank, the largest failure of a financial institution since Washington Mutual during the height of the financial crisis more than a decade ago.

Silicon Valley, the nation’s 16th largest bank, failed after depositors — mostly technology workers and venture capital-backed companies — hurried to withdraw money this week as anxiety over the bank’s balance sheet spread. It is the second biggest bank failure in history, behind Washington Mutual.

While the two banks served different markets and had different customer bases, the proximate cause of the failure of each was simply running out of money—a.k.a., a “liquidity crisis”.

One signature element of most liquidity crises: rising interest rates, and in 2022 interest rates rose because Jay Powell wanted them raised.

Two points deserve mentioning straight away, in order to have a workable context.

First, a liquidity crisis event is always a risk when interest rates are forced up, and financial markets unbalanced as a result. This has always been the paradox at the core of Jerome Powell’s inflation fighting strategy—raise interest rates far enough and there are not enough dollars at crucial junctures in global financial systems.

The second point is that Wall Street—i.e., Silvergate and SVB—have known all along that Powell’s rate hikes could and would lead to a liquidity crisis somewhere in the world of finance. They’ve known, and yet they still were caught exposed when the catalyzing events behind the liquidity crisis hit.

With Powell’s war on inflation concluding its first full year, and with another rate hike looming when the FOMC meets on March 22, the moment of crisis appears to be right now. The liquidity crisis is happening, it is unfolding in the crypto space and it has already claimed at least one “traditional” bank in SVB—the 2nd largest bank failure in US banking history, behind Washington Mutual of GFC infamy.

Will there be others? As was the case during the Great Financial Crisis, we won’t know which banks will fail until they fail—at which point it will be too late to do anything about the failure. The answer to the question is a perpetually unsatisfying “maybe.”

While the post-mortem on Silicon Valley Bank is still unfolding (it’s demise was that rapid, as it suffered an 80% share price collapse just within the past month), enough information has come to light to allow us to say with confidence that SVB’s problems began when their investment portfolio of US Treasuries (and other interest-bearing assets) kept losing value as the Fed pushed interest rates higher.

Finally deciding to offload the permanently impaired portfolio, Silicon Valley Bank found itself needing fresh capital to shore up its liquidity while announcing the rather large loss on the asset sale.

Consequently, when SVB posted a $1.8 Billion loss on a $21 Billion sale of securities on Wednesday, March 8, SVB’s customers and depositors “freaked”, to put it mildly.

Additionally, earlier today, SVB completed the sale of substantially of its available for sale securities portfolio. SVB sold approximately $21 billion of securities, which will result in an after tax loss of approximately $1.8 billion in the first quarter of 2023.

Suddenly uneasy about SVB’s balance sheet, depositors rushed to pull their money out, causing a classic bank run, with the classic ending.

Silicon Valley, the nation’s 16th largest bank, failed after depositors — mostly technology workers and venture capital-backed companies — hurried to withdraw money this week as anxiety over the bank’s balance sheet spread. It is the second biggest bank failure in history, behind Washington Mutual.

To recap how interest rates turned lethal for SVB, the key element to remember is that SVB held a substantial portfolio of interest-bearing assets, almost all of which lost value in 2022.

In its annual report for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2022, SVB held some $16 Billion in Treasuries, with an average yield of 1.49%.

Note also that SVB held a variety of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), all of which were also low-yield assets, with the average yield on the entire portfolio being 1.56%

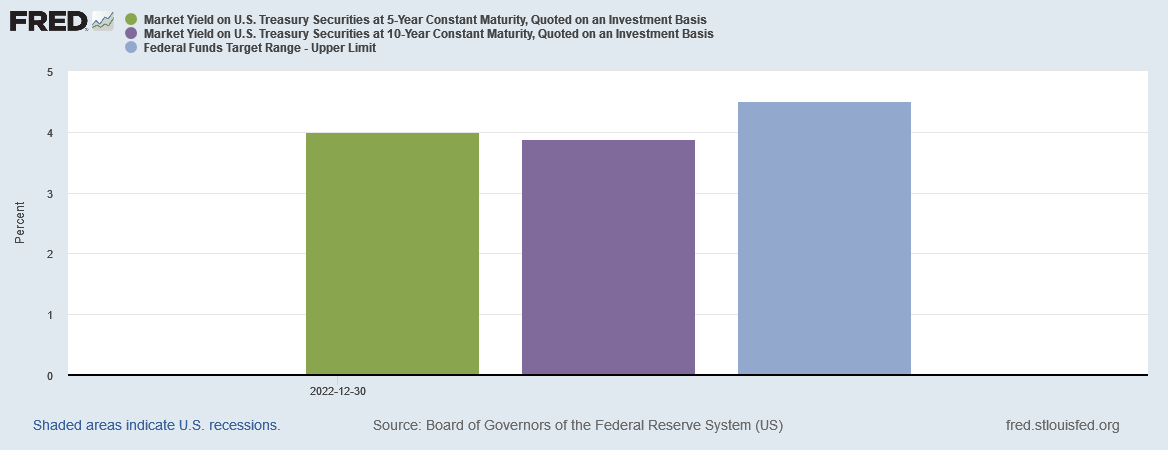

As of the last trading day in 2022, December 30, the 5-Year Treasury had a yield of 3.99%, and the 10-Year Treasury had a yield of 3.88%

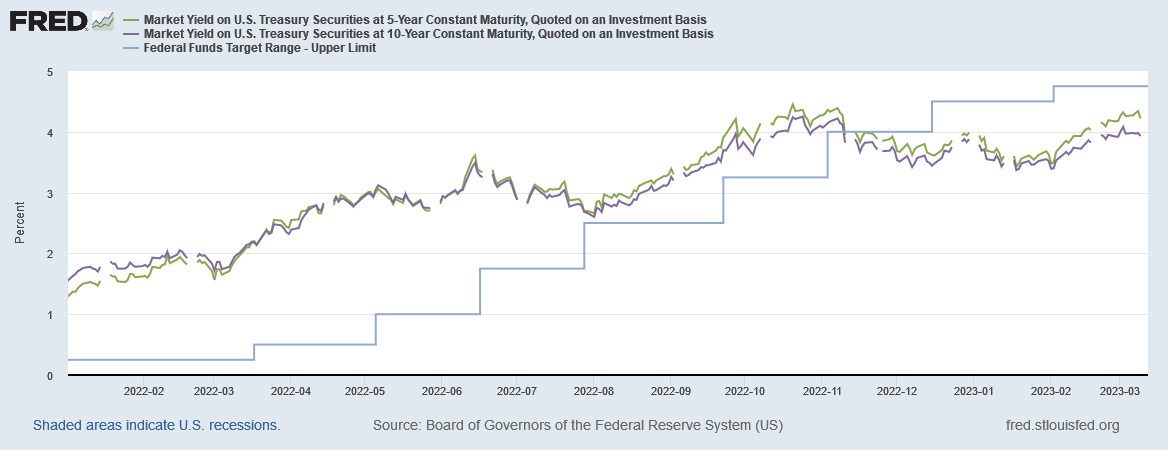

By the time SVB unloaded their interest-bearing portfolio, the yields on both the 5-Year and 10-Year Treasuries had resumed rising, after having plateaued and then declined during the last two months of 2022.

Even before yields resumed rising, however, SVB was already facing an interest rate environment where yields—market interest rates—were more than double the yield on SVB’s entire portfolio.

In other words, SVB was facing billions more in losses on its Treasuries alone, losses which were only going to increase as yields moved higher (and Jerome Powell wants yields to move higher). There was no way for SVB to recover that lost value on its assets, and the only thing left to do was to contain the damage by selling nearly the entire portfolio and swallowing the loss.

Unfortunately, when SVB had to disclose those losses, depositors were spooked enough so that the outcome was inevitable: a bank run, a liquidity crunch, a failure to raise needed capital, and then a full-blown liquidity crisis followed by sudden collapse.

Much of Silvergate’s woes are being traced back to the epic fraud that was FTX/Alameda Research, and which fell apart last fall as details of the fraud came to light.

If traditional finance folks and regulators saw crypto as something of a nuisance before, FTX’s collapse and the criminal indictments that followed turned the market radioactive. The closer you were to FTX, the more trouble you could be in.

“There’s an old saying — ‘if you lie down with dogs, you wake up with fleas’ — and that’s what happened with Silvergate,” John Reed Stark, an outspoken crypto critic and former head of the SEC’s Office of Internet Enforcement, told the Wall Street Journal. He described Silvergate’s collapse as a “cataclysmic event for the crypto industry.”

However, a quick perusal of Silvergate’s SEC 10Q filings suggests that the roots of its problems went deeper than an unfortunate choice of customers in FTX. Long before FTX was on anyone’s radar as a problem, Silvergate’s balance sheet was accumulating large interest-bearing liabilities, while their interest-bearing assets were shrinking.

At the end of March, 2022, Silvergate held some $3 billion in interest bearing deposits in other banks, and had taken $71 million in Federal Home Loan Bank advances to ensure adequate liquidity.

By June, the interest-earning deposits had shrunk to $1.4 billion, but the FHLB advances had risen to $397 million.

When Silvergate announced its 4th Quarter results at the beginning of January, the FHLB advances had disappeared from the financials, but some $4.2 billion of unspecified “short term borrowings” as well as $1.9 billion in interest bearing deposits was present on the liabilities side of the ledger.

Within the various notes attached to its 4Q results was a description of an $887 million loss connected with a sale of debt securities undertaken largely to discharge its FHLB loan obligations.

Noninterest Income (Loss)

Noninterest loss for the fourth quarter of 2022 was $887.3 million, compared to noninterest income of $8.5 million for the third quarter of 2022 and $11.1 million for the fourth quarter of 2021. The decline in the fourth quarter was due to losses on securities of $751.4 million and losses on derivatives of $8.7 million resulting from sale of $5.2 billion of debt securities and related derivatives that took place during the quarter. In addition, the Company recorded a $134.5 million impairment charge related to an estimated $1.7 billion of securities it expects to sell in the first quarter of 2023 to reduce borrowings.

While getting sucked into the maelstrom of the FTX fraud and collapse was not at all helpful for Silvergate, long before FTX was an investor’s problem Silvergate’s balance sheet was slowly moving off kilter, with rising interest rate expense against more slowly rising interest rate income. When the fallout from FTX triggered a run on Silvergate’s deposits, it could not maintain sufficient liquidity to honor all debt reclaimations by customers.

With interest rates continuing to rise, it was likely only a matter of time before a liquidity crisis took down the bank. The FTX fiasco merely had the curious fortune of being the catalyzing event for Silvergate’s immediate liquidity crunch.

As with Silicon Valley Bank, Silvergate’s demise was ultimately triggered by the rising interest rate environment instigated by the Federal Reserve and Jay Powell.

A point needs be made here for emphasis: The Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes are but one factor among a sea of issues surrounding the governance of each institution. The Federal Reserve did not push FTX to commit fraud on a scale to make Bernie Madoff blush. Jay Powell did not demand Silvergate bet big on doing business with the fraudulent FTX. Jay Powell also did not demand that SVB hold onto money-losing Treasuries at low yields even as he pushed yields higher.

Both Silvergate and SVB have been part of the mainstream banking system since well before 2022, and thus well before Powell started raising interest rates. Both banks have seen interest rates move steadily higher, while their respective lower-yielding securities steadily lost value. Both banks had over a year to address any prospective weakness in their liquidity strategies. Both banks failed to do so.

It has been glaringly obvious to anyone bothering to look that interest rates are rising globally—not just Treasuries, but corporate debt as well.

While the Federal Funds rate has been a problematic tool for raising interest rates over the past few months, during the summer last year was it was an effective tool for raising interest rates.

Yet the warning signs have been there that rising interest rates were going to cause problems for Silvergate, SVB, and potentially other banks besides.

Silvergate’s and SVB’s rising FHLB Advance loan balances are part of a broader trend in banking throughout 2022 to use the FHLB as a liquidity source, as FDIC data clearly shows.

One does not need a degree in finance to understand that SVB’s portfolio of low-yield Treasuries in an interest rate environment marked by rising yields was always going to be a source of material losses, and well before this past week.

By the time SVB moved to unload its portfolio of interest-bearing assets, the damage had already been done. Turning the unrealized losses into realized losses at least meant the damage could not get any worse.

Are there other banks with similar exposures about to go under? Indicators such as rising FHLB advance loans certainly suggest there might be, something I speculated could be the case two months ago.

The warnings we are seeing with rising FHLB advance loans and discount window usage are of a structural weakness within the banking system. A growing number of banks potentially are facing increasing difficulties in meeting funding and reserve requirements, and are increasingly resorting to emergency measures to cover their shortfalls. Slowly, and almost silently, the nation’s banking system appears to be growing more and more fragile.

How much exposure there might be is as yet a question. The discount window usage has not continued to rise, and so at a minimum we do not have that as a warning signal of coming liquidity crises at other banks.

However, the crises at Silvergate and SVB have helped catalyze a broad rout in the financial sector, with the S&P 500 Financials index falling to a 6-month low.

A survey of regional banks performed by MarketWatch in the wake of the SVB collapse identified 10 banks with significant exposure to low-yielding assets that could turn problematic as interest rates move higher.

It is probably a good sign that the larger “systemically important” institutions such as JPMorgan and Bank of America are not on this list—their presence would indicate another Great Financial Crisis event in the very near future. Yet the interest rate exposures of even the 2nd--tier regional banks are now a new challenge for the Federal Reserve to consider as it ponders what to do with interest rates.

It is a gross exaggeration to say that the Federal Reserve has caused these liquidity crunches by raising interest rates over the past year. Banks have had literally a full year to work out how to insulate themselves from the risks presented by a financial environment marked by rising rates—if they have failed to do so that can hardly be laid at Powell’s feet.

However, Jay Powell still has to consider the impact on the stability of the US banking system of future interest rate hikes. Regardless of what the banks did not do or should have done, Powell and the Federal Reserve have a legal as well as an ethical obligation to weigh the prospects of a significant destabilizing of the US banking system with future rate hikes, and not go out of his way to cause that destabilization.

Ideally, the Fed should take this moment to switch gears to a new inflation-fighting strategy.

If Powell persists in his obsessive interest rate strategy for attacking consumer price inflation, he is now running a very real risk of getting considerably more recession than he might want to see happen. While there has not (yet) been contagion enough to produce a GFC-style event, we cannot rule out that outcome, in which case pushing rates higher could prove significantly counterproductive.

Can Powell find a new path to take towards lower inflation without triggering more bank runs? Can he find an alternative to the mostly dysfunctional Volcker Playbook for combatting inflation and avoid inflicting unecessary economic pain? With the FOMC due to meet on March 21-22, we will not have to wait long to know the answer.

In the meantime, the wise man will pay attention to where Treasury yields head next, and check to make sure they are not about to run over his preferred bank in order to get there.