October JOLTS: Fewer Fake Job Openings, Labor Markets Still Toxic

Job Openings Remain A Giant Head Fake

The October Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey was either good news or bad news, depending on your perspective on US employment figures. What it was not was reliable and useful news.

The number of job openings decreased to 8.7 million on the last business day of October, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the month, the number of hires and total separations changed little at 5.9 million and 5.6 million, respectively. Within separations, quits (3.6 million) and layoffs and discharges (1.6 million) changed little. This release includes estimates of the number and rate of job openings, hires, and separations for the total nonfarm sector, by industry, and by establishment size class.

The biggest change was, unsurprisingly, in the number of job openings, which dropped far more than expected.

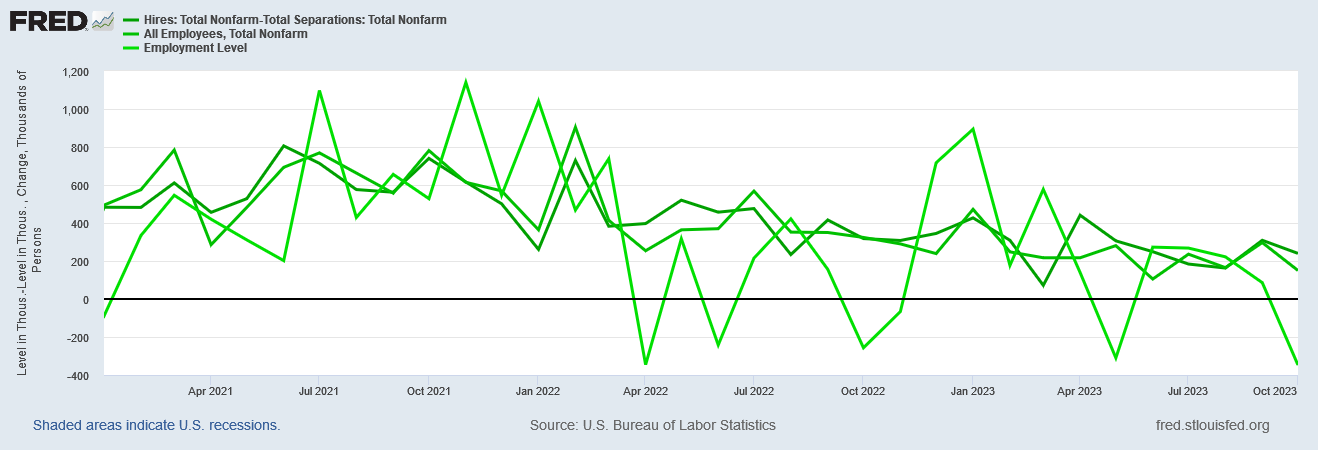

Yet the job openings data remains a giant statistical head fake, as the job openings numbers still have no good correlation to reality—despite the massive uptick in reported job openings after the Pandemic Panic Recession, there still has been no discernible increase in hiring to match. The presumed hiring pressures have not resulted in increased hiring—which undermines the legitimacy of the job openings straight away, and reminds us once again that job markets in the US are far more “toxic” than “tight".

Once again, Wall Street and the “experts” are looking at the wrong data.

Wall Street and the corporate media were predictably hyperfocused on the fundamentally fake job openings numbers.

Job openings tumbled in October to their lowest in 2½ years, a sign the historically tight labor market could be loosening.

Employment openings totaled a seasonally adjusted 8.73 million for the month, a decline of 617,000, or 6.6%, the Labor Department reported Tuesday. The number was well below the 9.4 million estimate from Dow Jones and the lowest since March 2021.

The decline in vacancies brought the ratio of openings to available workers down to 1.3 to 1, a level that only a few months ago was around 2 to 1 and is nearly inline with the pre-pandemic level of 1.2 to 1.

At the same time, the corporate media also continues to push the narrative that the “Great Resignation” phenomenon is a thing of the past.

Resignations slipped 18,000 to 3.628 million. The quits rate, viewed as a measure of labor market confidence, was unchanged at 2.3% for the fourth consecutive month. Declining quits point to slower wage growth and ultimately price pressures in the economy.

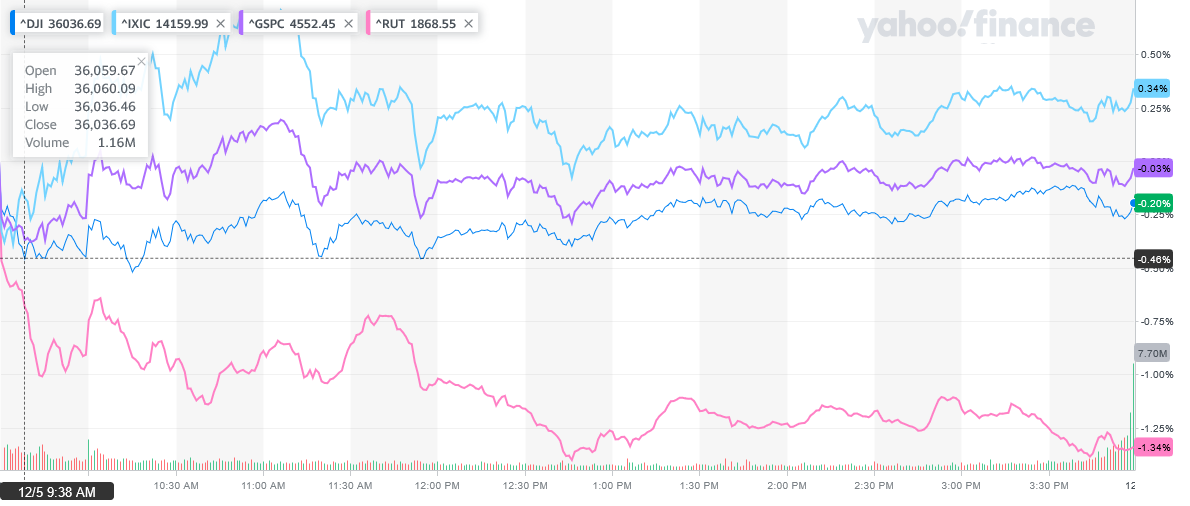

Despite the presumably “good news” for the Federal Reserve that labor markets were continuing to cool down, Wall Street was largely unimpressed by the JOLTS report. Equities were down slightly on the day, with only the NASDAQ showing any positive growth.

At the same time, yields dropped somewhat across the entire yield curve.

The job openings data may be good news for the Federal Reserve’s rate hike strategy for fighting inflation, but Wall Street gave it very little credence beyond that.

Nor should the job openings data be given much credence. Whether we look at the data with seasonal adjustments or without seasonal adjustments, the overall impact of the job openings numbers is the same: the shifts in job openings have had little or no impact on hiring and terminations.

There just has not been a major shift in either hiring or firing throughout the post-pandemic era.

Even the unadjusted data does not suggest there has been any significant increase in hiring or separations post-pandemic.

Before and after the pandemic and the associated Pandemic Panic Recession, hiring and separations remained in a fairly well defined range between 4,000,000 individuals hired or separated each month and either 7,000,000 (seasonally adjusted) or 7,500,000 (unadjusted) individuals hired or separated each month. The supposed doubling of job openings was insufficient to break monthly hiring patterns out of that range.

Even the hiring data itself is open to challenge, for while the net hiring each month (total hiring less total separations) roughly tracks to the Employment Situation Summary’s “All Employees” metric from the Establishment Survey, it does not align nearly as well to the change in employment per the Household Survey.

If anything, the JOLTS report is presenting an employment picture that is entirely too optimistic and which significantly overstates job growth in this country.

The historical perspective is helpful in understanding what the actual data trends from the JOLTS report are, and what they signify.

Most notably, we should acknowledge that reported job openings have been rising relative to hiring and separations since around 2015, even though actual hiring and seaprations have not shifted much at all.

However, even at that, there is nothing at all comparable in the available historical data which compares to the post-pandemic era’s surge in reported job openings. Even the net of hirings over separations, while having been larger in the post-pandemic era, has not shown the magnitude of increase that we see in the reported job openings numbers.

For the job openings data to be taken seriously, we would have to first explain how it is that such a surge in reported job openings produced no similar surge in net hirings over the same time frame.

The historical perspective also is important for understanding the observable shifts in the separations data.

Contrary to the media narrative, the increase in “quits” touted after the Pandemic Panic Recession as “the Great Resignation”1 has an origin far before COVID and the lockdowns. Quits began rising as a proportion of total separations sometime around 2013, and thus the Great Resignation phenomenon actually predates the COVID pandemic and all the economic disruptions which followed.

Because the Great Resignation predates the pandemic and the lunatic lockdowns, we must conclude that the causes behind the phenomenon are more systemic in nature, and are not of recent origin. This is confirmed by the fact that a rising quits rate is almost exactly offset by a rising hiring rate, with the result that the rising quits rate does little to alter the overall shape of the total separations chart.

Most importantly, the Great Resignation must be taken as an indicator that the labor markets are not “tight”, but rather “toxic”—people are more dissatisfied with their jobs in recent years than previously, and are opting to leave those jobs or simply not take the jobs in the first place.

The result is greater churn in the workplace, and greater employee turnover, but with ultimately little gain in overall employment. More people are changing jobs than new jobs are actually being created, something which is confirmed by the lack of dramatic shifts in layoffs.

Toxic labor markets which are showing little actual job growth is a considerably different narrative than what is being touted by the corporate media based on the chimerical job openings data. Toxic labor markets is a narrative which does not feed the larger narrative of a robust economy that powers on even as the Federal Reserve seeks to slow it down by means of interest rate hikes. Rather, toxic labor markets is a narrative that fundamentally argues the reverse—that the economy is struggling, is largely stagnant, and is becoming increasingly sclerotic.

Labor market toxicity is also the narrative that is far more grounded in reality than the corporate media narrative of tight labor markets in a booming economy. It is the narrative that emerges when one looks at actual hires and actual separations, and discounts the elevated job openings numbers as primarily wishful thinking on the part of employers.

Labor market toxicity is the narrative that suggests much less is changing in the jobs market than corporate media wants to admit. Far from labor markets “cooling” as the corporate media narrative suggests, labor markets are already largely “cold” and have been for a while. Actual job growth has been far less than the headline numbers suggest, which makes downward trends in hiring rather more problematic than they would be if labor markets and the overall economy were in better health than they are.

That is the real narrative fed by the October JOLTS report. Jobs markets which have been weak and struggling all along are getting weaker, suggesting that those parts of the economy not already in recession are likely to be in recession before long.

Corporate media will not talk about this, because corporate media has once again been distracted by the headline numbers and gives scant consideration to the details which lie underneath.

Fontinelle, A. “What Is The Great Resignation? Causes, Statistics, and Trends.” Investopedia, 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/the-great-resignation-5199074.