Speech Or Silence: Violence Is Not Speech

The First Amendment Does Not Protect Threats, Violence, Harassment, And Intimidation

How should we apprehend the plight of Mahmoud Khalil, who has been detained by ICE and is currently being processed for deportation, owing to his involvement in Columbia University’s pro-Hamas protests last year?

Should we be outraged that his rights of Free Speech are being violated?

Should we be incensed that his right to peaceably assemble and seek redress of grievance has been nullified?

Should we be concerned that we might be likewise targeted for expressing political views contrary to those within the federal government?

The answer to all three questions is a simple and straightforward “No.”

The Columbia University “protests” were not peaceful, were not a peaceable assembly, were not speech, and so there are no First Amendment or Free Speech concerns which arise from consequences meted out to the participants.

Free Speech Is A Moral Imperative

Let us be clear: Free Speech is a moral imperative. Our moral obligation to ourselves is to not shy away from any speech, no matter how noxious the rhetoric. I believed this when I wrote in defense of Nation of Islam leader and appalling anti-semitic hate merchant Louis Farrakhan and I believe it now.

My position in this regard is categorical: we must defend Free Speech at every opportunity or we are not a Free People and we do not have a Free Society.

When I say that Free Speech is a moral imperative, I mean exactly that: we are called and obligated to speak our various truths, and to hear the truths of others. Free Speech is foundational to a Free Society, and to the premise of democratic governance. Free Speech is foundational to honest, upright, and ethical conduct. Free Speech is essential if we are to embrace human equality as a fundamental moral truth.

Having experienced censorship and cancellation for daring to challenge the prevailing “official” COVID narratives on LinkedIn, I can speak directly to the damage done when we do not defend the rights of all dissident voices, regardless of the disagreeable nature of their woreds.

In discussing the strange case of Mahmoud Khalil, we must keep the ideal of Free Speech always in our minds, not because Khalil is a martyr for Free Speech as some would claim, but because he is not, as even a brief survey of the coverage regarding the Columbia University protests fom last spring will establish.

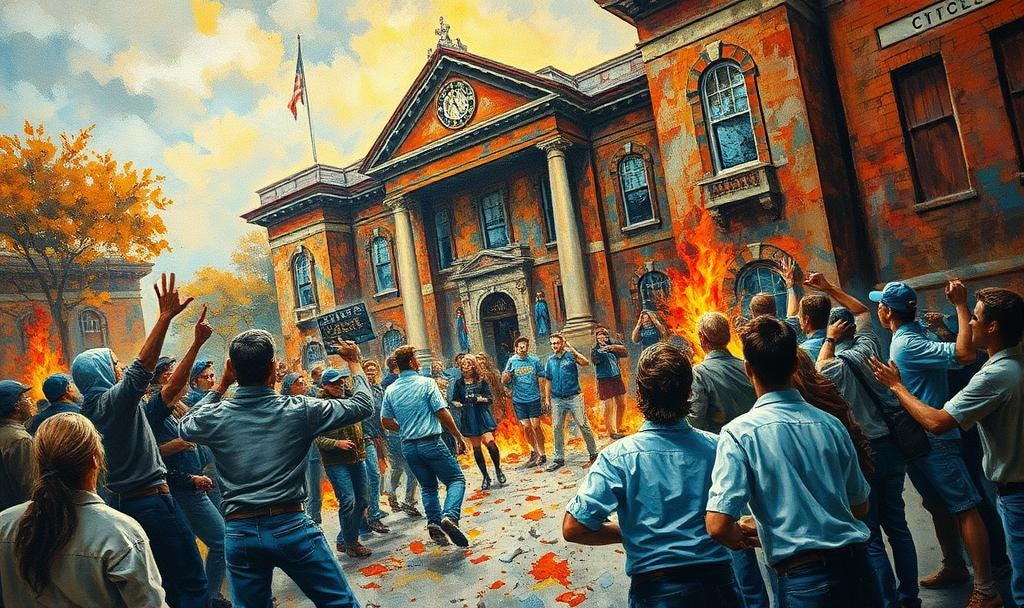

Columbia University “Protests” Were Not Peaceful, Therefore Not Speech

Any time we approach the topic of Free Speech, particularly here in the United States, we do well to keep in mind the full text of the First Amendment.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

When we evaluate the propriety of various protest actions, we necessarily engage with two of its articulated freedoms:

The freedom of speech.

The freedom to peaceably assemble.

Because a protest necessarily involves action as well as words, we inevitably find these two freedoms inextricably intertwined, to where the peaceable assembly becomes indistinguishable from the speech. However, as both freedoms are categorically protected from legislative abridgement within the text of the First Amendment, we are permitted the reductionism of simply labeling protests as speech.

There is, however, one caveat: for the reductionism to remain valid, the protest actions themselves must be “peaceable”. As with all terms Constitutional, this is a word with a specific meaning, both in modern apprehension and that of the 18th century.

The modern Merriam-Webster definition proceeds as follows:

1 a : disposed to peace : not contentious or quarrelsome

The Webster dictionary of 1828 yields this definition:

PE'ACEABLE, adjective Free from war, tumult or public commotion.

So long as a protest is not contentious, not quarrelsome, and free from tumult or public commotion, we may apprehend it as a mode of speech, which is to say a mode of Free Speech, and therefore protected from abridgement or circumscription.

However, the Columbia Univeristy protests of last spring were not at all peaceful. There was tumult. There was public commotion. They absolutely were contentious and quarrelsome.

When the media reporting quotes the “protestors” making statements about “Burn Tel Aviv to the ground”, we are well past the point of debating contentiousness.

“[Izz ad-Din] Al-Qassam [Brigades], make us proud, take another soldier out,” anti-Israel demonstrators chanted on Friday night in a video published on social media by pro-Palestinian activist ThizzL. “We say justice, you say how? Burn Tel Aviv to the ground. Go Hamas, we love you. We support your rockets too.”

Nor do we need to question the accuracy of the media reporting, as we have via social media video footage of that very chant.

We have protesters shouting at Jewish students of Columbia University that “the 7th of October is going to be every day for you.”

These are threats of violence. In the latter case, it is a specific threat of terroristic violence against a specific individual.

This is harrassment. This is intimidation. This is not peaceable assembly. This is not speech.

This fails the “Brandenburg Test”1, a legal formulation from Brandenburg v Ohio2 whereby incitement to imminent lawless action becomes itself actionable.

When a protest against the actions of the nation of Israel cause Jewish individuals at Columbia University to fear for their safety, it is harrassment, not speech. That was the case last spring.

Rabbi Elie Buechler, director of the Orthodox Union-Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus at Columbia/Barnard, wrote on Sunday morning in a group chat with over 290 students that “The events of the past few days, especially last night, have made it clear that Columbia University’s Public Safety and the NYPD cannot guarantee Jewish students’ safety in the face of extreme antisemitism and anarchy.”

When Columbia University can assemble a 91-page report detailing how Jewish students were physically harassed and assaulted, that is intimidation and violence, not peaceable assembly and not speech.

Jewish students at Columbia University were chased out of their dorms, received death threats, spat upon, stalked and pinned against walls, as the Ivy League school devolved into a cesspool of antisemitic hate in the wake of Hamas’ Oct. 7 murderous raid on Israel.

When classes have to be canceled for fear of student safety, we are dealing with violence, not speech.

When Jewish students are advised to leave Columbia University for their own safety, we are dealing with violence, not speech.

Such is the nature of the “protests” in which Mahmoud Khalil elected to participate.

Support For Terrorism Not Allowed

For Khalil, who entered the United States on a student visa and later became a permanent resident alien (Green Card status), the support for Hamas is a problem, and a major one.

Section 212(a)(3) of the Immigration and Nationality Act3 specifically prohibits engagement in any form of support for terrorism or terrorist groups when applying for a visa.

People who wish to enter the United States cannot demonstrate on behalf of, advocate for, raise money for, or otherwise show support for Hamas, or for any other terrorist organization. That is the plain reading of immigration statutes.

Moreover, Congress is explicitly authorized—and required—to legislate requirements for immigration and naturalization within Article 1 Section 8 of the Constitution. Congress has both the right and the responsibility to enact such restrictions on whom is eligible for a visa and thus entry into the United States.

There is no inalienable right of entry. There is no inherent claim of right to a visa. Such a right does not exist within the pantheon of US civil rights, nor has it ever existed.

Nor is this a new circumstance. This has always been the state of US immigration law, and, as I have argued previously, immigration is a question of law, not of “justice”.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio made substantially the same case earlier this week when appearing on Face The Nation with Margaret Brennan, who required a bit of education on the matter (education Secretary Rubio masterfully provided).

Margaret Brennan: I want to ask you about a decision you made to revoke a student visa for someone at Columbia University this past week. The Wall Street Journal editorial board writes, the administration needs to be careful. It's targeting real promoters of terrorism, not breaking the great promise of a green card by deporting anyone with controversial political views. Can you substantiate any form of material support for terrorism, specifically to Hamas, from this Columbia student? Or was it simply that he was espousing a controversial political point of view?

Secretary Rubio: Well, not just the student. We're going to do more. In fact, every day now, we're approving visa revocations. And if that visa led to a green card, the green card process as well.

And here's why. It's very simple. When you apply to enter the United States and you get a visa, you are a guest. And you're coming as a student, you're coming as a tourist or what have you. And in it, you have to make certain assertions. And if you tell us when you apply for a visa, I'm coming to the U.S. to participate in pro-Hamas events, That runs counter to the foreign policy interest of the United States of America. It's that simple.

So you lied. You came. If you had told us that you were going to do that, we never would have given you the visa. Now you're here. Now you do it. So you lied to us. You're out. It's that simple. It's that straightforward.

Nor is there any question that Mahmoud Khalil understood the dimensions of the protests in which he chose to participate, as he acknowledged a concern to the media over risking his student visa.

Khalil added that he chose not to participate directly in the student encampments because he did not want to risk the university revoking his student visa.

He understood that these protests would—or at least could—devolve from defensible if noxious speech and venture into areas of actionable conduct (i.e., support for terrorism). He chose to participate in them anyway.

He chose to participate in actions which articulated clear and unequivocal support for the terrorist organization Hamas. The very nature and intent of these “protest” actions was specifically to show support for Hamas. Indeed, statements such as “the 7th of October will be every day for you” are explicit expressions of support for Hamas.

Mahmoud Khalil chose to participate in “these” protest actions.

He chose badly.

Citizenship Matters

We must understand the fundamental distinction here between a citizen of this country and a non-citizen, even one who is here lawfully, with a valid visa and/or resident alien status.

By law, a “United States citizen” is understood to be a citizen of the United States either by law, birth, or naturalization4. As a citizen, such a person has the full panoply of rights available under US law5.

A person here on a student visa is not a citizen.

A person here with permanent resident status is not a citizen.

Non-citizens are by definition here on the sufferance and approval of the United States government. Non-citizens are here subject to the regulations and restrictions as defined by the Congress excercising its Constitutional mandate under Article 1 Section 8. Non-citizens can be deported when those regulations and restrictions are violated.

A citizen is not subject to deportation as a consequence of showing support for terrorism or a terrorist group. A non-citizen is subject to deportation as a consequence of showing support for terrorism or a terrorist group. That is how the law reads, that is how the law operates, and that is the Constiutional order of things.

People are going to have their opinions about Israel’s war with Hamas. Some people will favor the Arabs in Gaza. Some people will favor Israel. This will be true for citizen and non-citizen alike. The First Amendment extends to the speech on both sides full and categorical protection. The First Amendment does not extend to threats, violence, harassment, or intimidation on either side any protection.

Just as speech is not violence, violence is not speech. At Columbia University, the “protests” were not speech, but violence. Regardless of what might have been intended by the protest organizers, violence is what resulted.

Thus, there is no First Amendment issue at play here. There was no speech, thus the First Amendment is not involved.

Had the Columbia University “protests” not devolved into anti-semitic violence, harassment, and intimidation, Khalil favoring the Arabs in Gaza would not be a problem.

Had the Columbia University “protests” remained peaceable—had they remained speech—Khalil favoring the Arabs in Gaza would not be a problem.

The protests did devolve into anti-semitic violence, harassment, and initimidation.

The protests did not remain peaceable. The protests did not remain speech.

For Mahmoud Khalil, that’s a problem, and it should be.

Wex Definitions Team, Legal Information Institute. Wex: Brandenburg Test. Jun. 2022, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/brandenburg_test

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969)

Wex Definitions Team, Legal Information Institute. Wex: citizen. Jan. 2022, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/citizen

Exactly right, Peter, and exquisitely stated!

When I was growing up, virtually everyone understood that you have a right to speak your mind, but if you threaten or harass someone you could be charged with “verbal assault”. That’s a crime, so don’t do that! You didn’t have to have a barroom brawl, just threatening a person with physical harm was an assault. Why don’t people know this anymore? I’m blaming the same school system that no longer teaches how our government functions (“Civics”), or the responsibilities that come with being a U.S. citizen.

I walk into a bank and hand a teller a note. “Give me all your money, or else face the consequences.”

She does. I leave and 20 minutes later I am Surrounded by SWAT.

I say to SWAT “you are violating my free speech rights!”

SWAT looks puzzled and after mulling it over says “well gosh durn it. He is right! You have a good day, Sir.”