The BEA Wants You To Believe Inflation Is Down And Incomes Are Up.

Look To Your Wallets For The Reliable Data

There is no doubt that the Bureau of Economic Analysis is as addicted to positive spin on bad numbers as their brethren at the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Both bureaucracies give numbers that look good at first but completely fall apart on closer scrutiny.

The latest evidence of this dysfunctional trend is the BEA’s December Personal Income and Outlays report for December 2022.

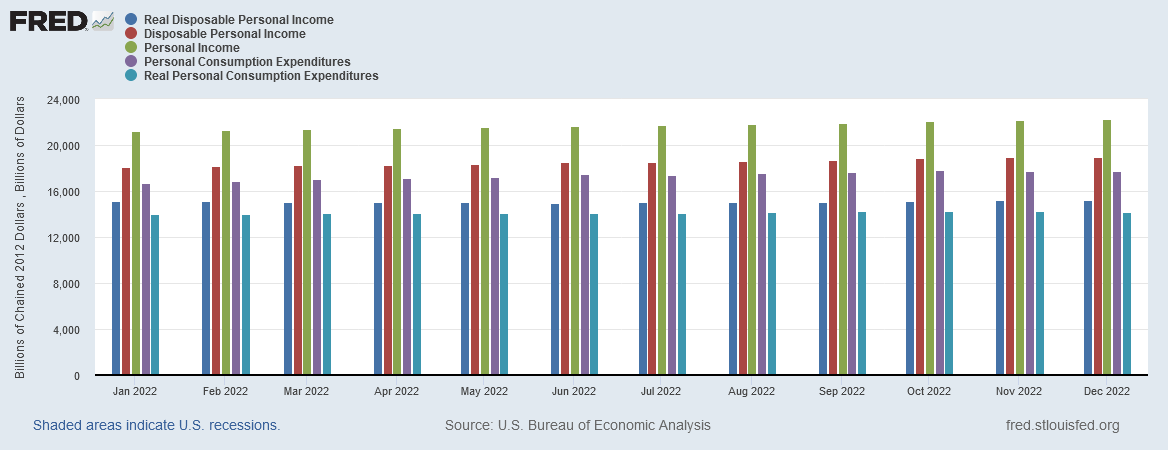

Personal income increased $49.5 billion (0.2 percent) in December, according to estimates released today by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (tables 3 and 5). Disposable personal income (DPI) increased $49.2 billion (0.3 percent) and personal consumption expenditures (PCE) decreased $41.6 billion (0.2 percent).

The PCE price index increased 0.1 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index increased 0.3 percent (table 9). Real DPI increased 0.2 percent in December and Real PCE decreased 0.3 percent; goods decreased 0.9 percent and services were unchanged (tables 5 and 7).

Incomes increased and expenditures decreased—surely that’s good news, right?

Well….perhaps. Only if inflation isn’t skewing the statistics. Oh, wait…it is.

It is perhaps too easy to overlook the significance of consumer price inflation, as it has been a staple characteristic of government economic data for decades (insert overdone metaphor about frogs and boiling water here if you like). Yet consumer price inflation is still very present and particularly lately, all too significant—which is made apparent even in the BEA news release with their table of PCE data.

We can begin to see the impact of consumer price inflation overall when we look at these numbers on an annual basis.

President Asterisk is hoping you’ll be happy to accept just the cherry-picked headline numbers and not drill down into the 2022 numbers by month.

When we drill down in to the 2022 numbers by month, however, we immediately see that the presumed gains disappear after inflation is considered.

As it turns out, consumer price inflation eliminates most presumed growth in disposable income, and in fact renders it as negative for the first six months of 2022.

When we roll the monthly data back up to a yearly basis, we immediately see two things:

Real disposable income fell for all of calendar 2021 and 2022.

Consumer price inflation rose for all of calendar 2021 and 2022.

Which makes President Asterisk’s tweets about inflation and income growth both ironic and economically illiterate.

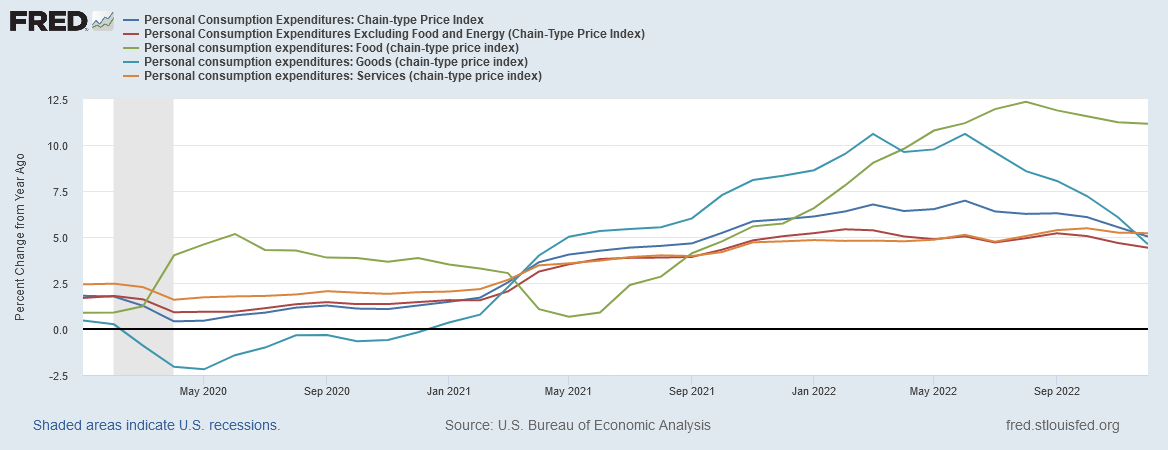

One thing we must always understand about inflation, and in particular consumer price inflation, is that the real economic damage lies in the degrees of distortion inflation inflicts on the prices for various goods and services within the economy. Not everything increases in price at the same rate at the same time, which skews what we pay for individual items (and thus impacts our overall buying decisions).

Thus while some elements of consumer price inflation have fallen a little, others have fallen a lot, and some have even gone negative (i.e., turned into consumer price deflation).

We see this distortive effect when we look at the various elements that go into consumer price inflation even at the year on year rate of change.

While energy price inflation (and deflation) clearly is the most volatile and therefore has the most impact on overall inflation, when we filter out energy price inflation we are still left with significant variation among the elements of inflation.

So long as these distortion keep occurring among the various consumer price inflation elements consumer price inflation will continue to be a burden for the economy. “Beating” inflation requires ending the distortions and dislocations.

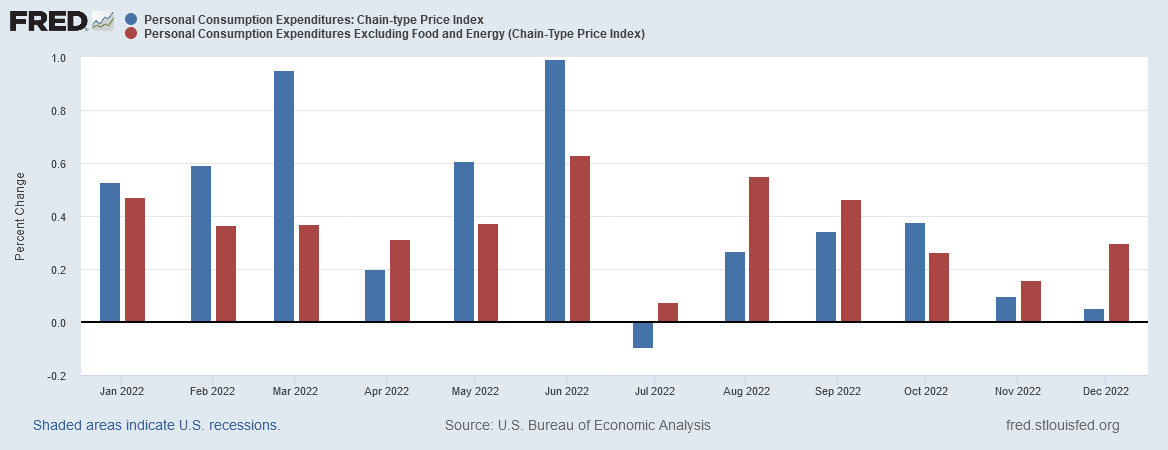

If we zero on 2022 and look at the percent change in the sub-divisions of the Personal Consumption Expenditures index, we begin to see how the impacts of various price fluctuations shift relative price structures within the overall economy.

When we filter out energy price inflation at this level, focusing on just the headline metrics for inflation, we see how the steep drop in energy price inflation starting in July had a muted impact on overall price changes.

Headline consumer price inflation did decline significantly, but the shift was far less dramatic in no small part because food price inflation has been far slower to decline.

Moreover, if we focus on “core” consumer price inflation—i.e., consumer price inflation without food and energy prices included—we see even more distortions unfolding.

Consumer price inflation for goods shifted to deflation for the second half of 2022, yet because consumer price inflation for services remained problematic, so to did core consumer price inflation.

Thus we can see the bottom drop out of headline consumer price inflation during the second half of 2022, with far more muted shifts within the core metric.

As a result of these distortions, not only have consumers faced shrinking disposable incomes over the past year, but have also had their purchasing choices artificially constrained. Inflation means price changes do not reflect evolving consumer preferences and desires, but rather represent the relative degrees to which those preferences and desires are no longer gratified.

Through such distortions and disruptions, inflation erodes the individual’s overall prosperity. Ultimately, high consumer price inflation produces declines in overall economic output. Paying more to buy less is not any realistic notion of economic growth.

President Asterisk wants you to believe that everything is rosy within the US economy because, at the headline level, he can point to a few numbers and claim that incomes are rising while consumer price inflation is declining. Yet the detail numbers underneath the headline numbers put the lie completely to his words.

The truth of the economy is that incomes are not rising, but are falling, and have been for the past couple of years.

The truth of the economy is that even as consumer price inflation is trending down at the margin, the disruptions and distortions it imposes across the broader economy remain and are still strong enough to constrain consumer choices.

That is not a set of economic circumstances which will increase individual prosperity—not now, not ever.