The Breaking Begins: BoE Intervention Halts The Rise In Yields At The Expense Of Everything Else

Is The Next Great Financial Crisis Beginning?

A few days ago, I offered up an assessment of recent market signals to the effect that a “SHTF” moment was imminent, and that global financial mechanisms were about to break in a spectacular way.

The very next day, the Bank of England capitulated in its inflation fight, intervening in the market to halt rising yields on UK 30-year Gilts (bonds).

Soon the reasons for the intervention became clear: Rising yields were driving Britain’s pension funds and housing markets into a collective meltdown, highlighting pension fund exposure to that old nemesis of market stability, derivatives.

The problem centred on the use of niche financial products offered by investment banks to pension funds that are trying to manage or hedge their risks. Those products – known as liability-driven investing, or LDIs – help offset liabilities and risks on pension funds’ books.

However, as asset prices slumped over the week – including UK government bonds, or gilts – those banks required more collateral to offset the pension funds’ liabilities, forcing the funds to dump assets and raise cash at short notice.

Rising yields on gilts (yields move inversely to price, and a rising yield means a falling price) were triggering margin calls among UK pension funds, a scenario eerily reminiscent of 2007/2008 just before the Lehman Brothers collapse.

Relative to the size of global markets, the BoE intervention was short and small. Yet its catalysts within UK markets are of a kind to raise the question whether we are witnessing the beginning of the next Great Financial Crisis.

British Housing Market Headed For Major Meltdown?

The other catalyst driving the BoE intervention was what could be the beginning of a major crisis in British real estate, as soaring yields plus uncertainty over recent budget pronouncements by Britain’s new government under Prime Minister Liz Truss threatened to drive interest rates—and thus mortage defaults—into dangerous territory.

One homeowner told MailOnline: 'Like thousands of others, we’re currently buying a new property and our current mortgage offer expires soon. It's quite possible that we’ll have to pull out of the sale, as I suspect thousands of others will too. That’s because our current bank, HSBC, won’t offer a new product'.

Lenders have also scrapped 1,000 deals in 24 hours with interest rates heading towards six per cent following Kwasi Kwarteng's 'mini budget' last Friday.

There are also an estimated 200,000 so-called 'mortgage prisoners' in the UK who are already on variable rate deals and unable to remortgage.

Much like the bursting of the housing bubble in 2005-2007 in the US, when 45% of mortgage originations were for Adjstable Rate Mortages (ARMs), the relatively high proportion of UK homeowners with variable rate mortgages means the British housing market is facing a wave of potential defaults as homeowners can neither make payments once their mortgage interest rate resets nor refinance their property to at least kick the mortgage interest rate can down the road a few years more.

Between a collapsing housing market and unexpected pension plan margin calls, the BoE felt compelled to intervene to stave off a massive and chaotic correction.

Whether the intervention comes in time to save the housing market is another question. Despite announcing the intervention the previous day, British lenders still pulled thousands of mortgage offers, even as homeowners are putting their homes up for sale to get out from under the threat of unaffordable interest rate hikes.

Britain's housing market is stalling badly today with lenders pulling 1,000 mortgage deals and homeowners putting their houses up for sale because they cannot afford the cost of rising interest rates, estate agents have warned.

At most, the intervention buys a little time, as the fundamentals driving rates higher have not changed.

The Intervention Worked? Yields Say Maybe

Yesterday at least, yields on longer term gilts dropped. Where the 30-year gilt had been above 4% on its way to 5%, after the BoE made its announcement yields immediately fell below 4%.

Yields on 10 Year gilts also dropped significantly.

The yield drop spread across the pond to the US markets as well, with 2-Year, 10-Year, and 30-Year Treasuries posting signficant yield declines.

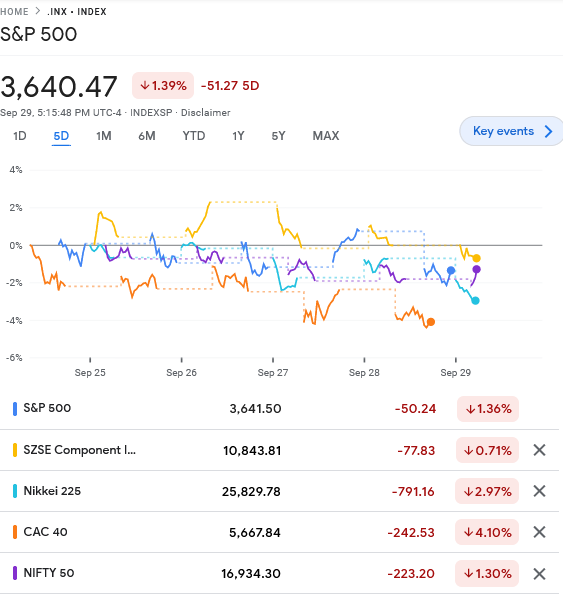

Equity markets, however, were not so impressed, as falling Treasury yields provided only a brief respite from the downward trend before stocks once again succumbed to gravity.

Globally, stocks have had a similarly bad week, BoE bond buying having no impact there either.

Simply put, Wall Street is spooked.

Liquidity Crisis Brewing?

As I have dicussed previously, central bank interest rate hikes to cure inflation run the risk of precipitating a general liquidity crisis, as rising interest rates trigger margin calls on a variety of assets to cover the increasing costs of financing. As shifting financial conditions force various investor hands, the potential for there being insufficient liquidity at crucial junctures to allow for orderly unwinding of asset positions rises. The Bank of England intervention appears to have been an effort to stave off just that among UK pension funds, as rising yields threatened their derivative positions—ironically taken out in order to hedge investment risk.

If this is indeed the case, then the BoE stepping in to buy gilts becomes a canary in the coal mine warning that another liquidity crisis similar to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis is forming. Although Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell has dug his feet in regarding the possibility of any pivot back to Quantitative Easing, the same debt dynamics that led Ben Bernanke down the QE road post-2008 are still very much part of the current financial landscape.

As the UK pension funds crisis demonstrates, even the derivatives at the center of the 2008 financial crisis are still around, merely packaged under different names.

If a liquidity crisis is brewing, it strongly suggests that the Fed’s goal of reducing its balance sheet is well nigh an impossibility. The Fed cannot shrink its balance sheet without shrinking the money supply, and shrinking the money supply means fewer dollars available to settle transactions at any given moment. At the same time, rising interest rates mean more margin calls and refinancing activity, placing greater demand for dollars within financial markets. The very act of fiscal prudence Powell so dearly wants to complete becomes the very thing that could force the Fed back into imprudence to ensure financial markets continue to function.

If the goal of ensuring liquidity is to kick the debt can down the road, consumer price inflation and the Fed’s insistence on sticking to the questionable Volcker playbook means the markets have at last run out of road. The time for reckoning becomes now—today, not tomorrow, and not the day after next year.

Central banks (principally the Fed at this point) have few good options. A pivot to QE now means signalling surrender on inflation—never mind that the Fed’s battle with inflation has been pretty much pointless—telling both Wall Street and Main Street that inflation is now the new normal. Staying the course means risking a wave of defaults, leading to a wave of bankruptcies. How far the contagion would spread and to what extent Main Street would be infected by Wall Street is an unanswerable question.

The Fed desperately needs a new playbook to replace the Volcker playbook on inflation. Is Powell the man to write such a playbook? So far, the evidence is not encouraging.

"margin calls among UK pension funds"

What the hell is a pension fund doing buying bonds on margin?

Sure, you can make more money when the price of an asset is increasing by buying it on margin, but the problem is if the price of the asset decreases, a margin call will wipe you out. I'm somewhat aghast that pension funds are allowed to use margin at all, and I'd really like to know what their leverage ratio was on these "investments".