The Diesel Demand Narrative Surrenders To The Data

Instead Of "Shortage" Now The Concern Is "Demand Destruction"

In the end, narratives must always yield to the data. The data are what depict reality; the narrative is merely one perspective on that reality.

Our latest demonstration of this principle comes courtesy of corporate media’s backpedaling on their narrative of diesel demand.

As has been noted previously, diesel demand for some time has been far softer than the corporate media has wanted to admit.

Now the corporate media is conceding that diesel demand is possibly not as great as previously reported, although their explanation is that high prices have “finally” killed diesel demand.

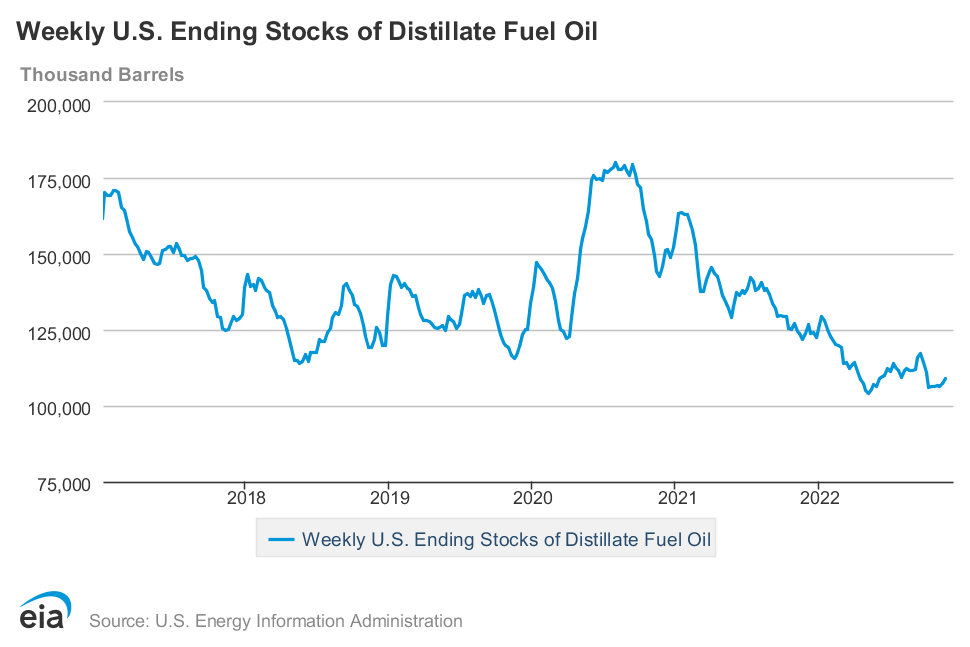

High prices seem to have started to weigh on diesel demand in the United States, where distillate inventories – comprising diesel and heating oil – have been slowly rising over the past few weeks. American distillate inventories are still below the five-year average, but the gap in stocks compared to previous years has slowly started to narrow, suggesting that high prices are hitting demand, while encouraging more refinery output thanks to solid refining margins.

Before, diesel demand was outpacing supply to the extent that a shortage of the motor fuel was feared. The “shortage” concern has faded, and “demand destruction” concerns have taken its place.

Diesel Inventories Have Trended Down For Years

While diesel inventories are indeed at their lowest levels in years, the reduction in inventories is not a recent evolution, but is the result of a long-term downward trend in diesel supply.

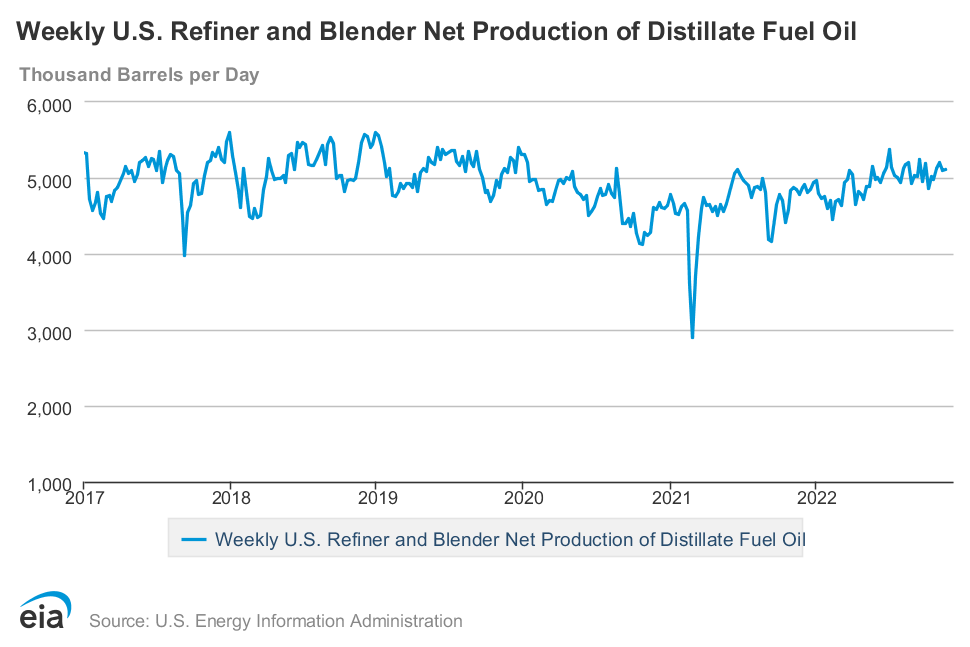

Moreover, while inventories have declined, production has not, and has even increased recently.

While inventories have been on decline since 2020, diesel production has remained more or less stable over that same time. This indicates that refiners looked at the post-pandemic demand as something of a correction after the lockdowns, and relied on the existing inventory to buffer that demand while maintaining production volumes.

Thus the entire “shortage” concern was always completely illusory. Producers simply anticipated that demand would eventually taper off, at which point inventories would begin to recover—which is exactly what is happening now.

Prices Have Been High For Some Time Without Diminishing Demand

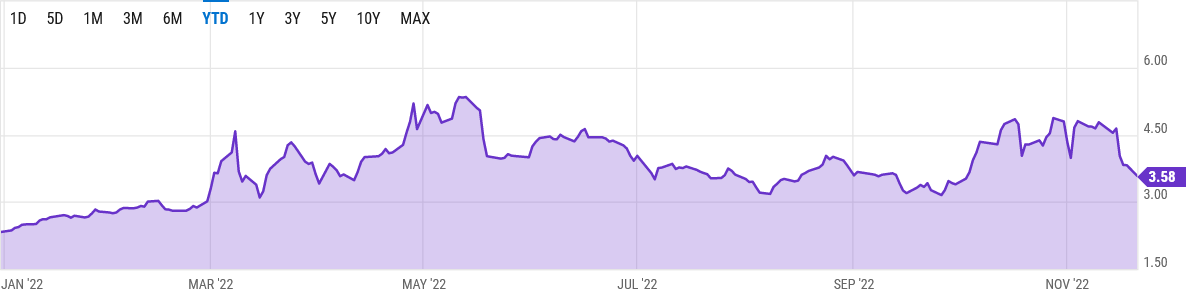

Also working against the notion that high diesel prices are choking off demand is the reality that diesel prices surged early this year, and while they are slow in returning to even the already-elevated 2021 levels, they too have been trending down since the summer.

Demand was quite willing to endure the higher prices throughout the spring and the summer, as evidenced by the inventory draws during the same period as the price surges.

Even the New York harbor spot diesel price shows that demand survived high prices, but the high prices did not survive a diminution of demand.

Thus there is demand destruction, in that demand for diesel has diminished to the point that production is sufficient to begin building back inventory. However, the timing of the price declines indicate that the high prices were not the cause of the demand destruction, but rather the demand destruction has led to a decline in those same high diesel prices.

In other words, the narrative has the dynamic exactly backwards. Diesel markets are simply responding to the fluctuating state of diesel demand, and are behaving quite rationally in this regard.

Why The Demand Destruction?

If high prices are not the proximate cause of the reduction in diesel demand, the question to ask is “what else could cause the demand for diesel to drop?”

A full analysis of all the variables that feed into diesel demand would greatly exceed the length limits of a single Substack article, but we can still posit a few broad hypotheses to explain it.

In particular, as a primary source of the demand for diesel is over-the-road trucking, a drop-off in diesel demand would be expected when the demand for trucking and other elements of intermodal shipping taper off.

The drop in maritime shipping rates towards pre-pandemic levels certainly indicates a decline in the demand for physical goods. With fewer goods being shipped across the oceans, there are naturally fewer goods to be transported via truck from the nation’s ports.

With the United States hovering on the brink of a recession, and growth in Europe already falling off the cliff, the prospects for further economic expansion are indeed dramatically reversing. "Fears of rising inflation and an economic downturn are weighing on the demand for goods," Stamer said, driving down the "need for shipping space and the level of freight rates" at the same time.

Thus we have clear indicators that the decline in diesel demand is not the result of high diesel prices, but is symptomatic of a broader and deeper economic contraction, as US consumers reduce their purchases of physical goods, whether the result of high inflation, spikes in interest rates courtesy of the Federal Reserve, or the impacts on individual consumers of that broader and deeper economic contraction.

Diesel demand is but the latest confirmation that the United States is not about to enter a recession, but has already entered a recession. Economic contraction is not a future threat but a present reality. Economic contraction is happening; economic contraction is here.

The corporate media narrative has at least caught up to the reality of softening demand. However, by conflating the effect of diesel price declines with the cause of softening diesel demand, the corporate media is still giving a fundamentally inaccurate and misleading view of the state of the nation’s economy. Instead of acknowledging the reality of the current recession, the media is perpetuating the fable that economic contraction is not (yet) happening.

However, the data is unambiguous on this point: Economic contraction is happening; economic contraction is here.

But isn’t the inflation in prices for goods somewhat of a reflection of shutting down oil pipelines and exploration?

That an economic contraction was coming has been predictable since at least the second quarter of the year.

IMO, high diesel prices will lead to *some* demand destruction. Example: I own a couple of diesel vehicles as well as some gasoline powered ones. The diesel ones are bigger, but due to the greater efficiency of a diesel engine there's normally no fuel cost penalty to drive them. Now currently, with retail diesel prices ~50% higher than retail gas, there certainly is, so if I don't *need* one the bigger, diesel powered vehicle, I'll drive one of the gas ones instead. Is my personal diesel demand destruction negligible? Sure, but multiply this scenario by a few million guys who own diesel pickups, while their wives have gas powered cars, and it might just add up to something that matters. And demand did fall off quite a bit this spring right around the time when diesel prices really went through the roof:

https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/weekly/images/dispsusm.gif