The prevailing wisdom within economic circles is that the US is currently enjoying a very strong labor market.

Unfortunately, this prevailing wisdom is more like epic cluelessness, and a paradoxical lack of essential curiosity that is essential for any good analysis. Despite what the BLS said in July’s Employment Situation Summary, or what Jay Powell said in his brief address at Jackson Hole1, the labor market in the US is not strong, but is toxic and particularly vulnerable.

Despite the seeming strength of the headline numbers within the Employment Situation Summary, the reality of the data is that the numbers underneath simply do not add up, not without some truly vaudevillian mental gyrations—hence my naming them Lou Costello Labor Math.

Why The Labor Market Appears Strong

The most obvious reason for declaring the labor market in the US “strong” is simple and straightforward: the unemployment rate is at 3.5%, one of the lowest unemployment marks in the postwar era.

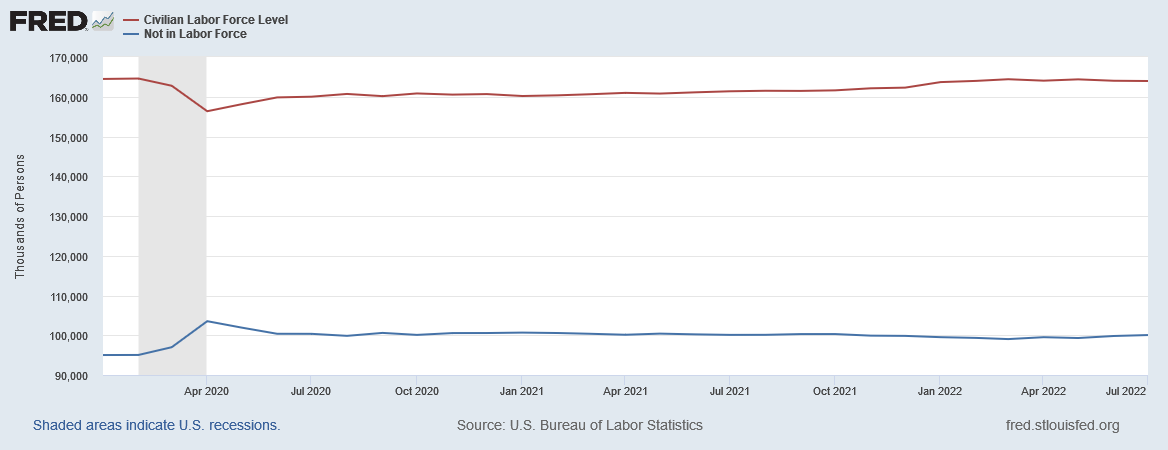

When you look at the civilian labor force data, the labor force appears to be increasing, with the number of persons not in the labor force decreasing.

That the labor market is tight is amply demonstrated by the reality that there are twice as many unfilled job openings as there are currently unemployed persons to fill them.

Could one ask for more from an economy? Well…yes. One could (and should) ask an economy to have a consistent unemployment situation, something the US does not have currently.

Divergence Between Seasonally Adjusted Data And Raw Data

The first indication that something is off kilter within the employment data comes when one looks at the civilian labor force data—both the raw data and the seasonally adjusted data—on the same graph.

Note how the seasonal curve and the raw data curve diverge beginning around March of this year. All things being equal, that should not happen over that long a time frame for seasonally adjusted data.

Seasonal adjustment2 is a technique applied to time-series data to eliminate seasonal shifts within the data due solely to the varying seasons. Eliminating such time-related shifts eliminates statistical "noise", and helps to bring meaningful statistical relationships to the foreground.

The math behind a seasonal adjustment is simple:

Compute the average of a complete time series (the long term average).

For BLS data which is given monthly, divide each month’s data by the long term average to get the seasonal factor (which can be expressed as a percentage or multiplied by 100 to be expressed as an index).

Repeat for each time series available as appropriate.

Compute the average for each month’s seasonal factor, dropping the higheset and lowest value.

Divide each month’s unadjusted data in each time series by the seasonal factor to derive the seasonally adjusted number for that month.

Because seasonality is built around the average across an entire time series, it is mathematically impossible for the seasonally adjusted data to diverge from the raw data across several months—the seasonal data is not going to increase for several months while the raw data decreases, or vice versa; the seasonal factors invariably pull the data closer to the time series average. Yet that divergence is exactly what we see in the Civilian Labor Force data.

If we index the raw data and the seasonally adjusted data to January of 2020, we see the divergence much more clearly.

We see the same divergence in the data for persons not in the labor force.

Again, indexing the data to January of 2020 makes the divergence much more evident.

If these divergences are not possible, all things being equal, then we are forced to conclude that, beginning in March, all things within the labor force are not equal. “Something” has changed within the data that is overwhelming the seasonal adjustment calculation.

The Labor Force Is Growing, But Slower Than Before

To analyze these divergences, we need to break apart the years and compare the raw data month to month across the years. To eliminate variation due to an expanding labor force, we index each year’s data to January of that year, thereby focusing on the relative magnitude and direction of data shifts.

If we do the same thing for the data on persons not in the labor force, we get the following:

In these views we begin to see why the raw data and seasonally adjusted data are diverging. After March of this year, even as the labor force increased in absolute terms, the increase has been proportionally slower than in recent years excluding 2020.

Similarly, for persons not in the labor force, after March there is also a slowdown in the pace of decline.

If we focus on just the seasonally adjusted data while spanning multiple years, this slowdown appears as a decline in the civilian labor force and a rise in people not in the labor force—the degree of slowdown is skewing the seasonal fluctuation more than is normal.

The Hidden Weakness

This deceleration of labor force growth is what Jay Powell and nearly every economic pundit in the chattering class has overlooked.

Throughout 2021 and the first few months of 2022, labor force growth was in large part more vigorous than it had been in 2019, and was only slighly less vigorous than 20183. After March, however, labor force growth has slowed significantly.

Even though the raw numbers show an increasing labor force, it is this slowdown in growth that allowed the labor force participation rate to slip down on a seasonal basis even while rising unadjusted and as the employment population ratio still manages to eke out a small increase.

An abrupt deceleration in labor force growth is an indicator of weakness, not strength. It is a red flag that suggests the labor force is about to decline in absolute terms as well.

That deceleration is evident within the data, once one delves into that data sufficiently. That one needs to look for such a deceleration is evident by the otherwise impossible divergence between the seasonally adjusted labor force figures and the raw data.

Neither Jay Powell nor the rest of the “experts” bothered to look for it. By ignoring it, they are misapprehending the state of US labor markets, and therefore miscalculating the impact of future rate hikes on those labor markets.

Powell’s hawkish stance on interest rates is about to cause significant job destruction in this country—a far larger price tag for corralling inflation than he has communicated thus far.

Powell, J. H. Monetary Policy And Price Stability. 26 Aug. 2022, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20220826a.htm. Delivered at 2022 Jackson Hole Economic Symposium. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

Majaski, C. What Is a Seasonal Adjustment? 18 Feb. 2018, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/seasonal-adjustment.asp. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

2020 is a completely anomalous year due to the pandemic lockdowns and the forced dislocation of tremendous numbers of workers, and for this reason comparisons to 2020 tell us almost nothing of the current state of labor markets.

"Powell’s hawkish stance on interest rates is about to cause significant job destruction"

Indeed, it is. But I can think of no alternative, can you?