The US Labor Market Isn't "Cooling", It's Already Cold

The Job Opening Numbers Have Been Pure BS For Months

The lede paragraph in the Wall Street Journal’s sudden realization of problems in the US labor market the other day was almost funny.

Demand for U.S. workers shows signs of slowing, a long-anticipated development that is showing up in private-sector job postings even while official government reports indicate the labor market keeps running hot.

The Wall Street Journal has only just now realized that the Job Openings number from the JOLTS report was completely ludicrous and not to be trusted. Seriously.

Wall Street’s favorite corporate media drones have clearly not been paying attention.

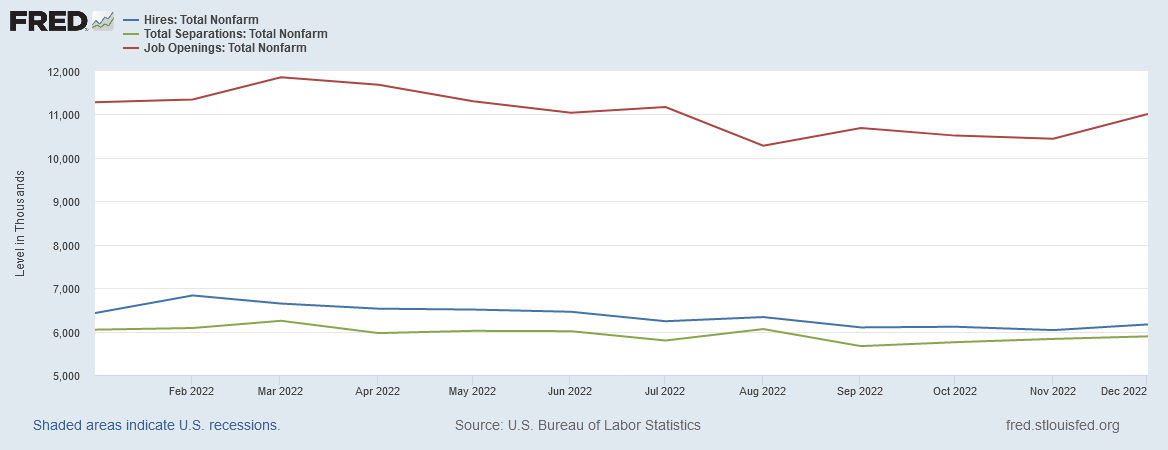

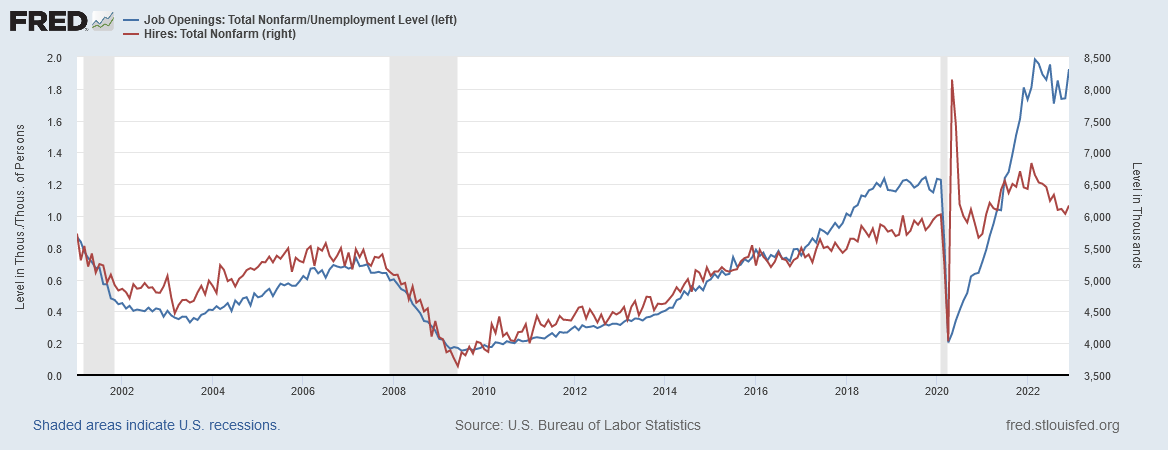

If we look at how job openings, hires, et cetera have shifted over time, we immediately see a major anomaly in the post-COVID data.

Despite the levels of hires and separations moving only gradually (the 2020 COVID lockdown months excepted), after the 2020 recession the job openings numbers surged to unprecedented levels.

If we focus on the post-COVID numbers, we still see that the hires and separations were largely unchanged, month on month, despite the surge in job openings.

Consider what this chart is showing: despite reported job openings nearly doubling during 2021, hiring changed little if at all.

During 2022, hiring actually declined, despite a continued high number of reported job openings.

This is the “robust” labor market that supposedly has been confounding Jay Powell’s efforts at labor demand destruction and recession creation.

A more plausible reading of the actual data is that the job openings being reported have been largely fictitious all along. The labor market in the US has been toxic rather than tight.

Nor is it just the job openings number that has been showing signs of stagnation and deterioration throughout 2022.

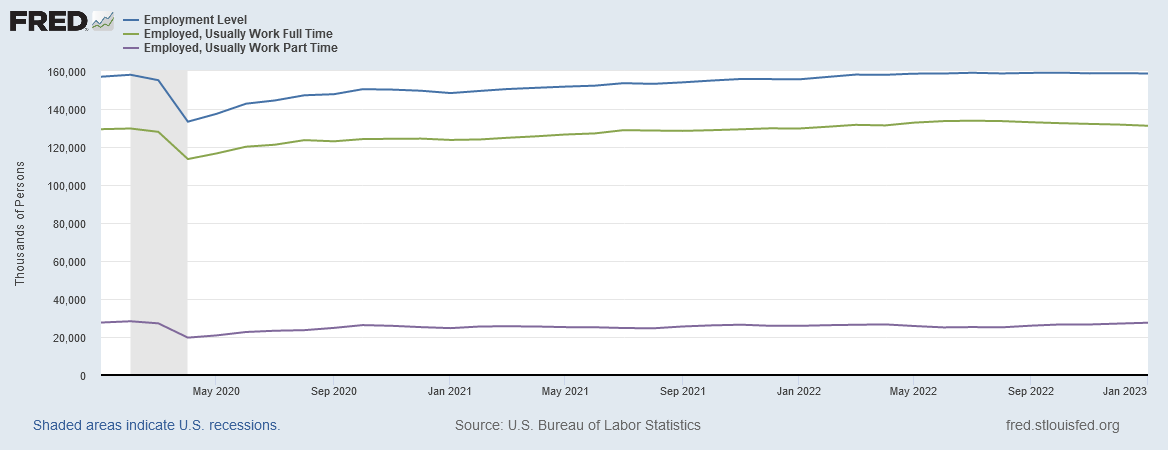

The overall employment level in the US of course sagged during the 2020 pandemic recession, but the most notable aspect of the historical employment data is that it shows minimal if any growth and improvement, with the employment level not actually returning to pre-pandemic levels until mid 2022. Again, this is hardly a metric indicative of a robust labor market.

More crucially to understanding the state of working America, however, is the reality that employment levels have not changed much in three years.

If we index the employment level to January 2020, and do the same for the number of full-time and part-time workers, we see that, over the past three years, the number of workers in the US, and the number of full time workers, increased by slightly more than 1%.

1% growth over a three year period is hardly the epitome of robust growth.

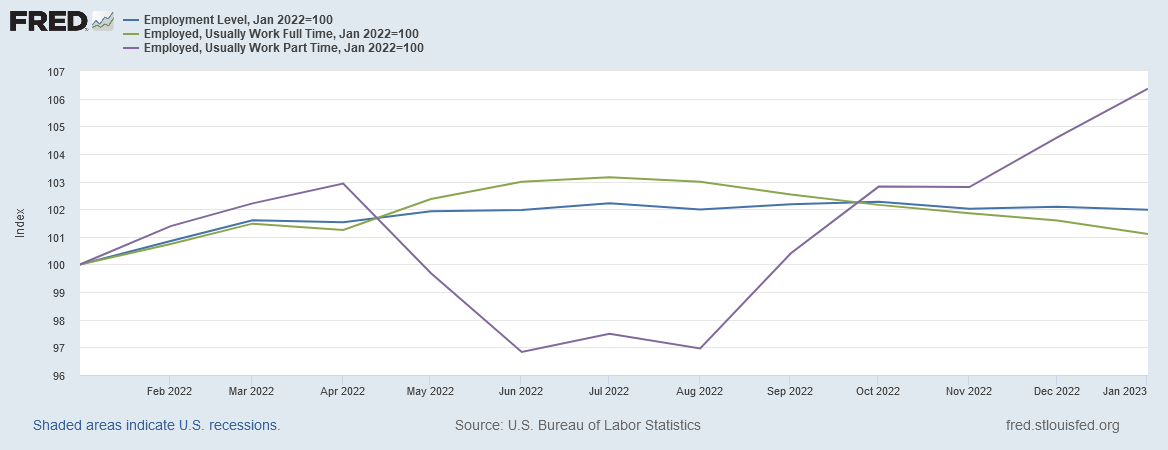

If we index the data to January 2022, we still see little growth in the workforce, be we also see that the number of full time workers peaked in mid-2022, and then began declining, while the number of part time workers surged in the latter half of the year.

Virtually all of the “growth” in the workforce in the last half of 2022 came from people considered to be working part-time.

Does that sound like a robust labor market?

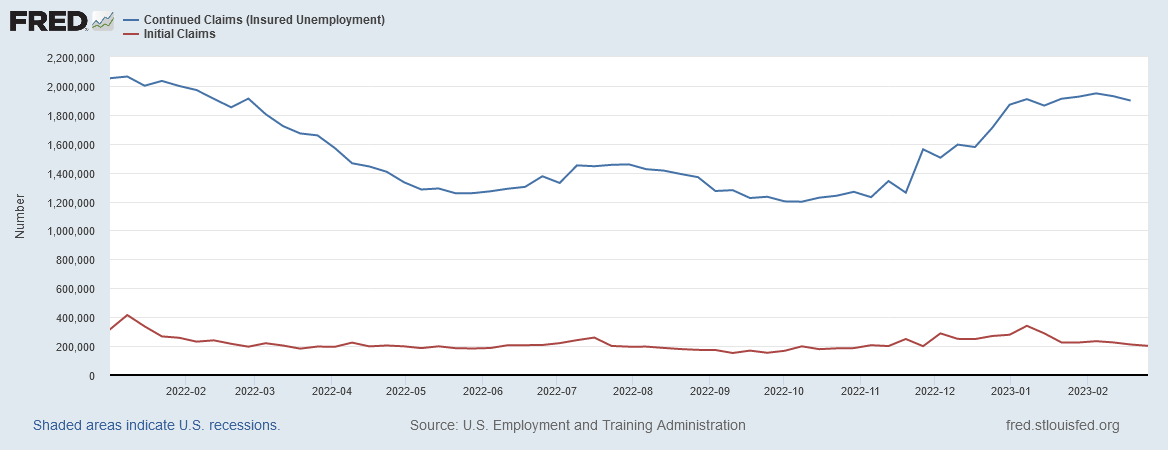

Looking at unemployment insurance claims for 2022, while the number of continuing claims (people out of work more than one week) declined through the first half of 2022, in the second half of the year the number of continuing claims began climbing once again.

That rising unemployment has indeed been the trend during the second half of 2022, if we look at the 4-week moving average for both continuing and initial claims, we see the same basic trend lines.

There are many ways to view and assess rising unemployment, but “robust labor market” is not among them.

The essential problem with the “robust labor market” thesis is that it ignores the degree to which the reported job openings data has simply not made sense post-COVID.

In the past two decades, the only times the number of job openings has exceeded the number of unemployed individuals has been from 2018 through February 2020 and from June 2021 onward.

Yet the only time the number of job openings per unemployed person has risen to the levels currently being reported has been from June 2021 onward.

Moreover, during the 2018-2020 interval, even though the number of job openings exceeded the number of unemployed individuals, the pace of hiring to fill those job openings rose.

During the post-COVID era, despite the even higher number of job openings, the pace of hiring actually fell from February 2022 through November.

Simply put, this sort of trend makes no sense. If employers are truly interested in filling large numbers of positions—which the data asserts that they are—the expected outcome would be an increase in the pace of hiring to fill those positions. The sheer number of openings itself should produce a pressure to hire people which should show up in the hiring data—and which we simply do not see in 2022.

Moreover, we also see that in July 2021, a few months after the point at which the number of job openings exceeded the number of unemployed—approximately May of 2021—the pace of hiring began to plateau before declining six months later.

This suggests that the jobs employers truly were eager to fill over and above normal job opening levels were filled by the summer of 2021. The continued rise of reported job openings beyond that point has to be viewed as a largely illusory number—the supposed demand for workers was simply not met by employers hiring more workers.

One interesting labor market behavior we do see both pre-COVID and post-COVID is that the excess of job openings above the unemployment level produces only a minimal amount of movement in the labor force participation rate.

Pre-COVID, the excess job openings translates into a roughly 0.5 percentage point improvement in the labor force participation rate, and post-COVID the labor force particpation rate plateaus at about the point where the excess of job openings over the unemployment level reaches a maximum. Merely having available jobs does not appear to be sufficient in and of itself to pull significant numbers of potential workers back into the labor force once they have exited it.

Taken altogether, it is simply not possible, given the responses within the labor markets that we have seen for the reported job openings, to regard the persistently high number of job openings as a “true” measure of employers’ interest in hiring. The job markets have never been as tight post-COVID as the JOLTS data appears to suggest at first glance. Rather, the JOLTS data coupled with the unemployment data portray a labor market that has a significant dysfunction on display—a seeming inability to effectively pull potential workers off the sidelines and back into the labor force.

As I have speculated before, the labor markets in the US are not “tight”. Rather, they are “toxic”, and remain so even now.

Without greater movement in the labor force participation rate, there is no rational foundation for regarding the current high number of reported job openings as being in any way a realistic benchmark of employers’ overall interest in creating new jobs. It does neither the employer nor the unemployed worker any good to report a job opening that, for whatever reason, cannot or will not be filled. Only when high numbers of job openings produce significant and sustained shifts in the labor force participation rate can they be taken as a realistic benchmark of overall labor demand.

Consequently, the correct way to view the labor market in the United States is that the demand for labor has not increased since approximately July of 2021, and has been in decline since February of last year.

In other words, no, the labor market is not “cooling”, as the “experts” are wont to believe. It’s already cold, and simply getting colder.