While Putin’s war in Ukraine is proving quite costly to Russia, it would be both foolish and unrealistic to pretend the costs are all one-sided. On the other side of this meatgrinder of a conflict the outlook is equally grim, and not just for Ukraine.

In economic terms, Europe as a whole is sure to pay nearly as big a price as Russia.

Indeed, it is easy to forget that Europe—which is to say the European Union—has been engaged in an economic contest with Russia that is every bit as stalemated and every bit as attritional as the military contest in Ukraine. Economic war may not produce the casualties that make military contests both appalling and barbaric, but it can be quite destructive in its own right.

Europe is on course to learn just how destructive economic warfare can be, and sooner rather than later.

While Europe may not be shedding any blood (yet) over the war in Ukraine, the question already deserves to be asked: how much treasure is Europe willing to pay over Ukraine?

There is little doubt but that war in Ukraine has not been at all kind to Europe’s economy.

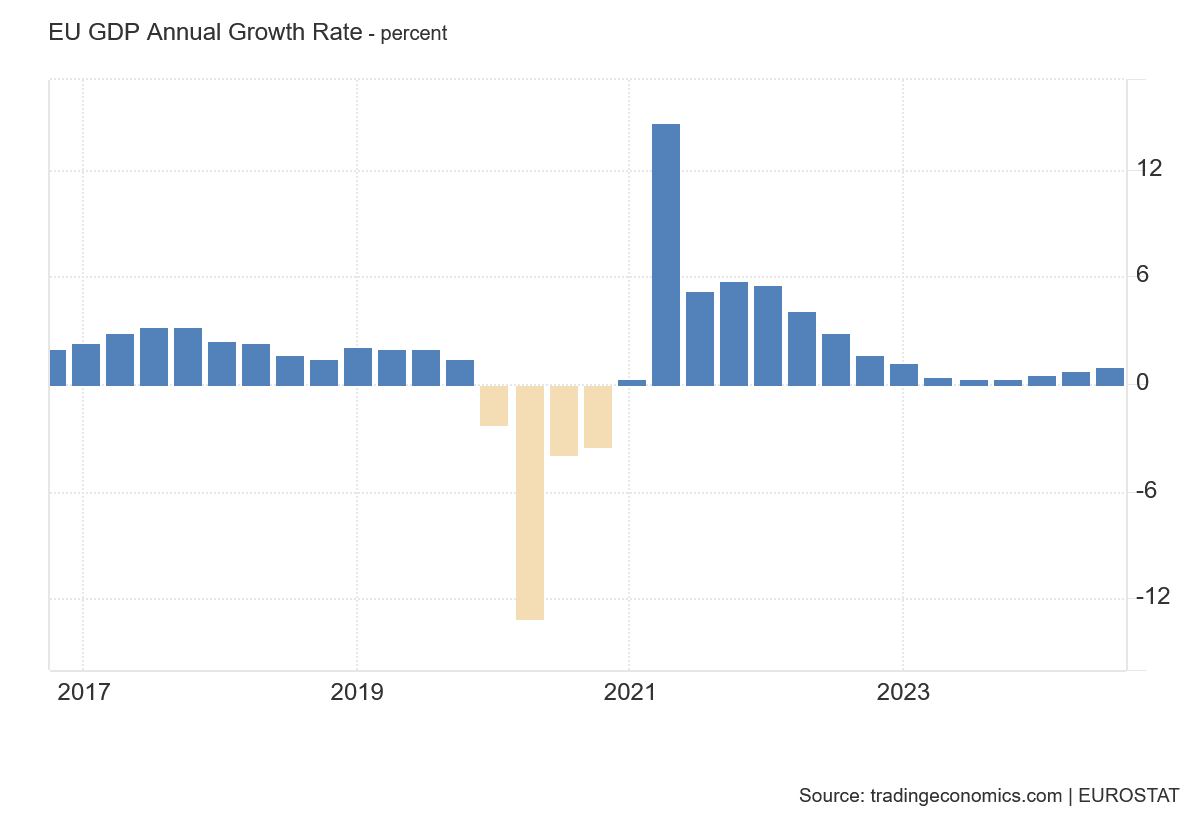

No sooner had Europe emerged from the severe downturn brought on by the lunacy of the COVID Pandemic Panic than it was confronted by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

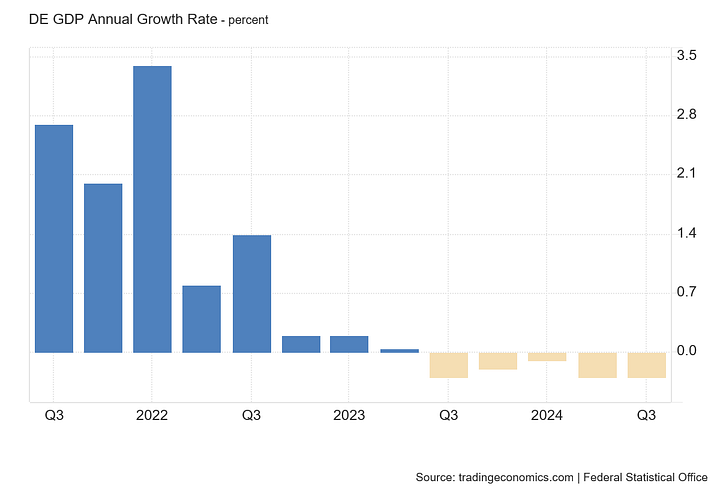

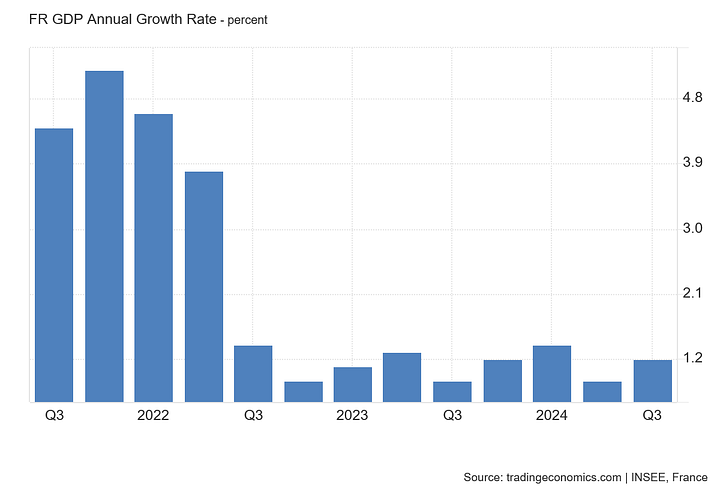

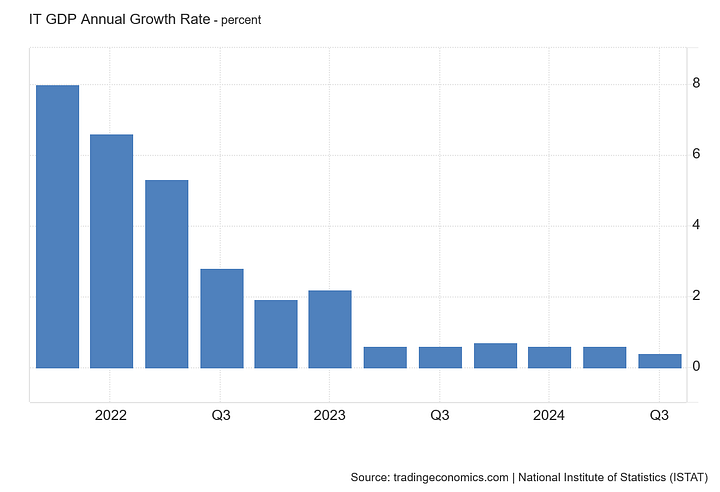

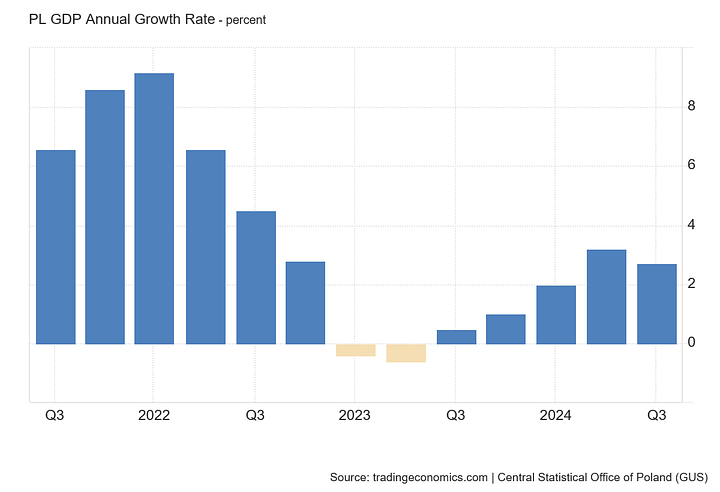

Economic growth within the EU quickly declined to a fraction of what it had been post-COVID, an absolutely foreseeable consequence of the sanctions the EU imposed on Russia in response to Putin’s invasion. Perhaps less foreseeable but no less inevitable, the economic deceleration by the end of 2022 had also reduced economic growth across the EU to less than what it had been pre-COVID as well.

When Europe moved to sanction Russia over Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, it was imposing trade sanctions on a major trading partner—at the time the European Union was Russia’s largest trading partner, with a trade relationship that looked to be growing for the foreseeable future.

That relationship was not small for Europe either—Russia was Europe’s fifth largest trading partner in 2021.

In 2021, Russia was the EU's fifth largest trade partner, representing 5.8% of the EU’s total trade in goods with the world.

In 2020, the EU was Russia's first trade partner, accounting for 37.3% of the country’s total trade in goods with the world. 36.5% of Russia’s imports came from the EU and 37.9% of its exports went to the EU.

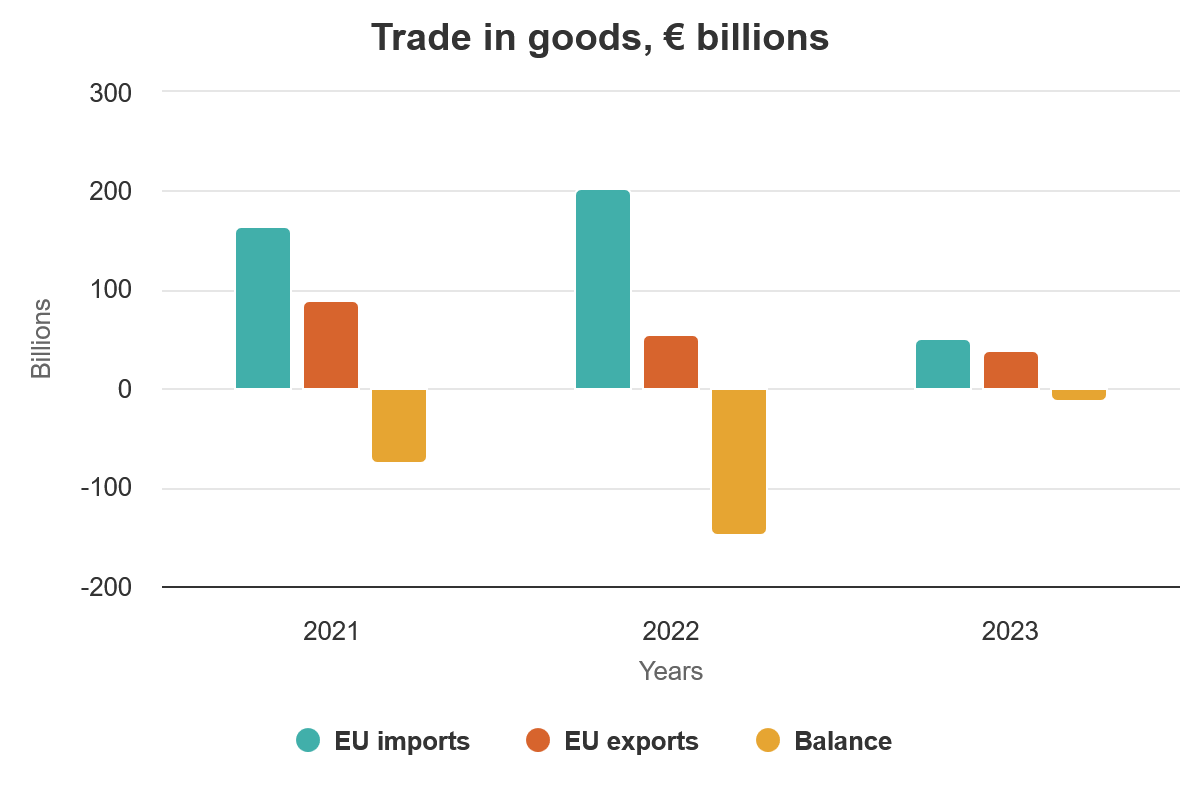

In 2021, the total trade in goods between the EU and Russia amounted to €257.5 billion. The EU’s imports were worth €158.5 billion and were dominated by fuel and mining products – especially mineral fuels (€98.9 billion, 62%), wood (€3.16 billion, 2.0%), iron and steel (€7.4 billion, 4.7%), and fertilisers (1.78 bn, 1.1%). The EU’s exports in 2021 totalled €99.0 billion. They were led by machinery and equipment (€19.5 billion, 19.7%), motor vehicles (€8.95 billion, 9%), pharmaceuticals (€8.1 billion, 8.1%), electrical equipment and machinery (€7.57 billion, 7.6%), and plastics (€4.38 billion, 4.3%).

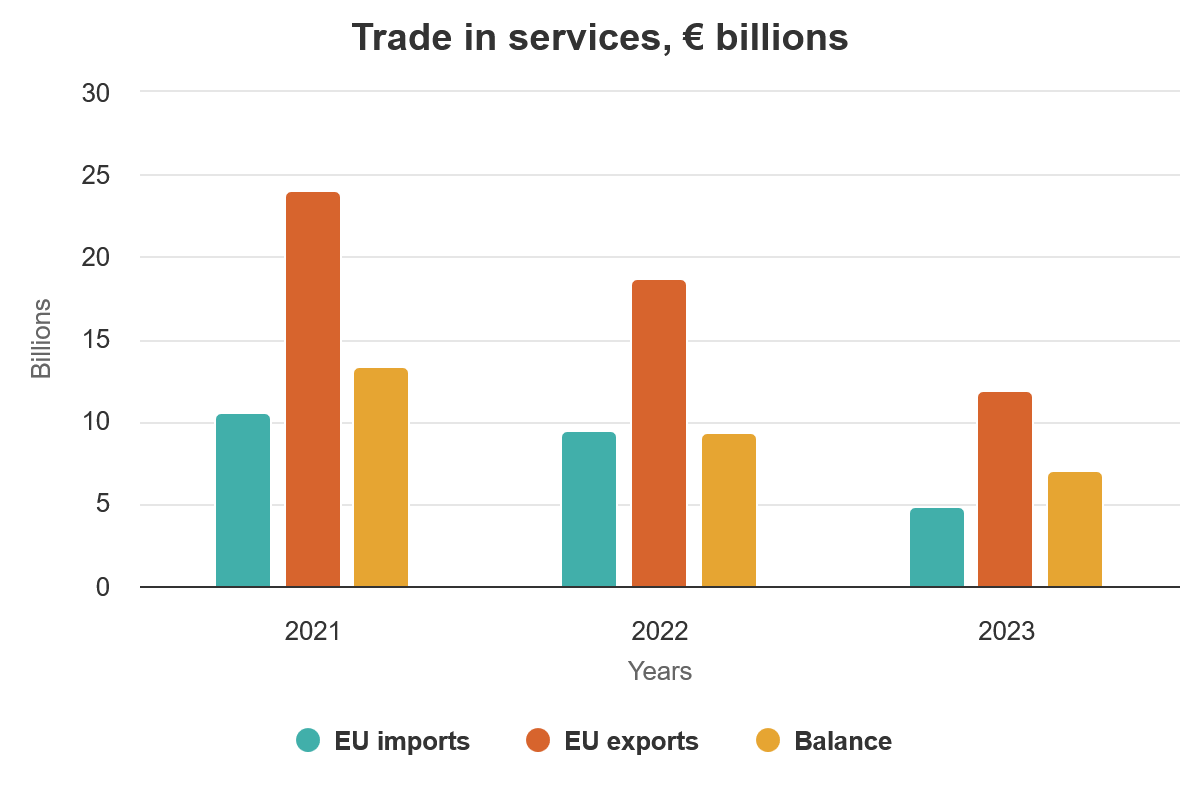

Two-way trade in services between the EU and Russia in 2020 amounted to €29.4 billion, with EU imports of services from Russia representing €8.9 billion and exports of services to Russia accounting for €20.5 billion.

In 2019, the EU was the largest investor in Russia. The EU foreign direct investment (FDI) outward stock in Russia amounted to €311.4 billion, while Russia’s FDI stock in the EU was estimated at €136 billion.

Between the war and the sanctions regime, EU-Russia trade has shrunk to a fraction of what it once was, both in terms of imports from Russia and exports to Russia.

The impact on the individual nations within the European Union of the sanctions regime was predictable: a considerable amount of economic growth was tossed away.

That the war in Ukraine was going to prove costly to Europe was a foregone conclusion even in 2022. Events since then have only underscored how much that cost would be.

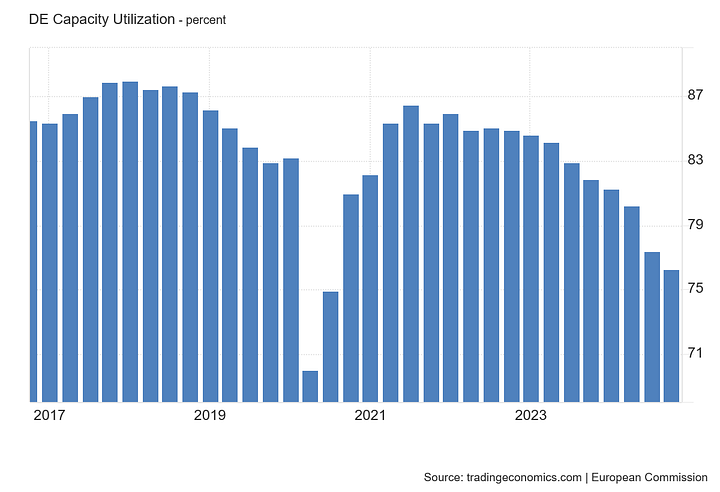

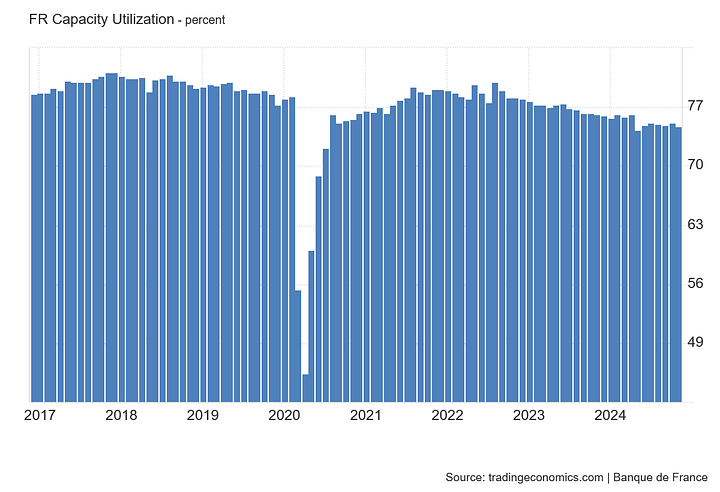

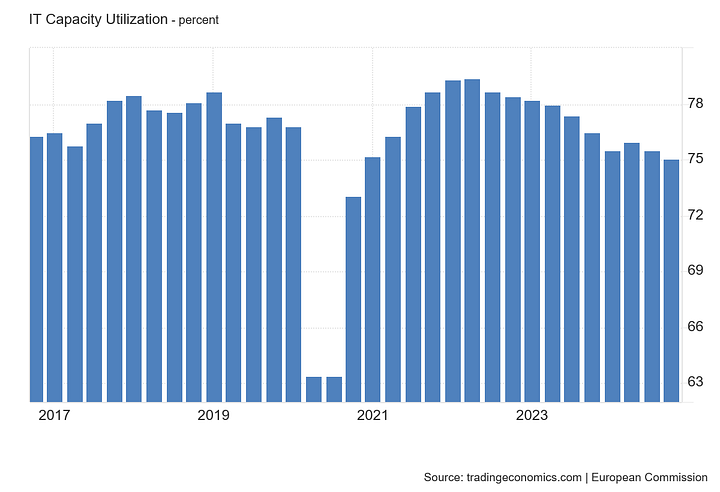

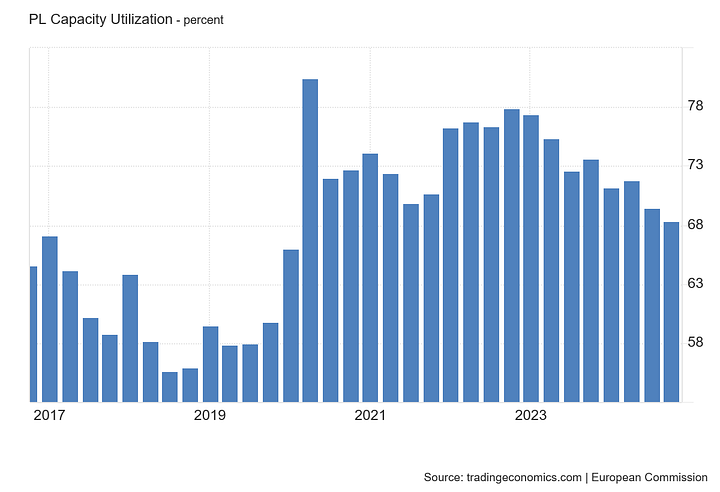

Nor has the economic slowdown in Europe been confined to a few countries or even a few economic activities. Europe’s capacity utilization has declined across the board since the war began.

The slowdown in Europe as almost immediate, and could hardly have come at a worse time, as the EU had just regained its pre-COVID level of economic activity.

No nation has been spared.

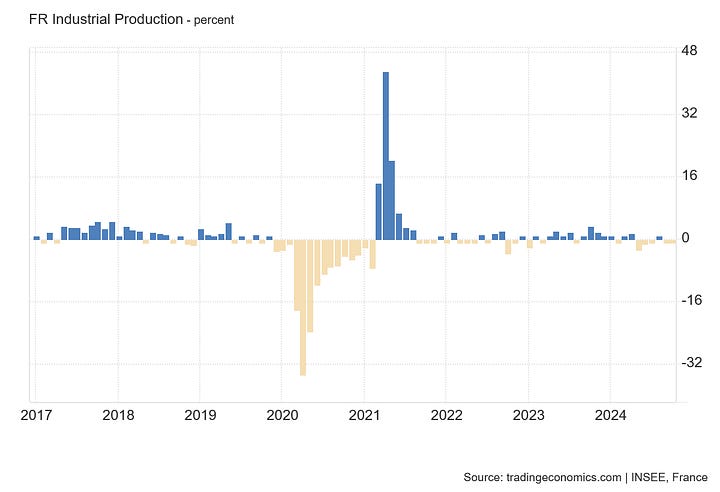

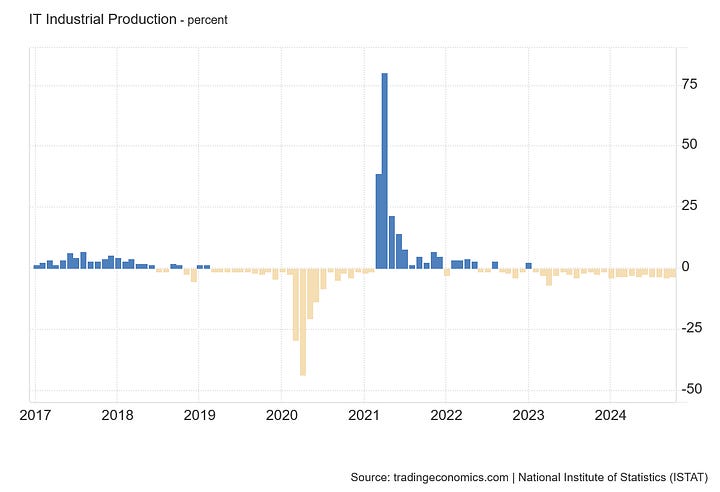

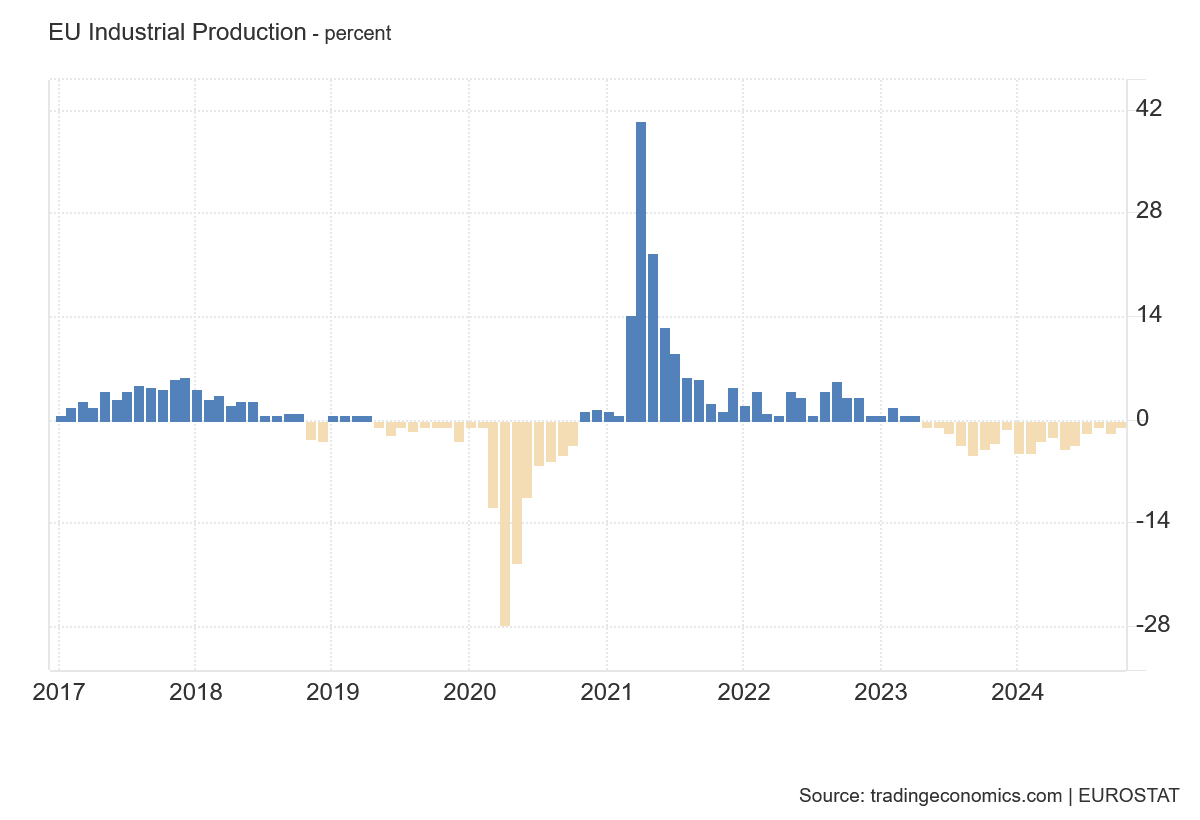

The decline in capacity utilization, however, was merely the prelude. The far more significant economic harm to the European economy has come in the form of de-industrialization.

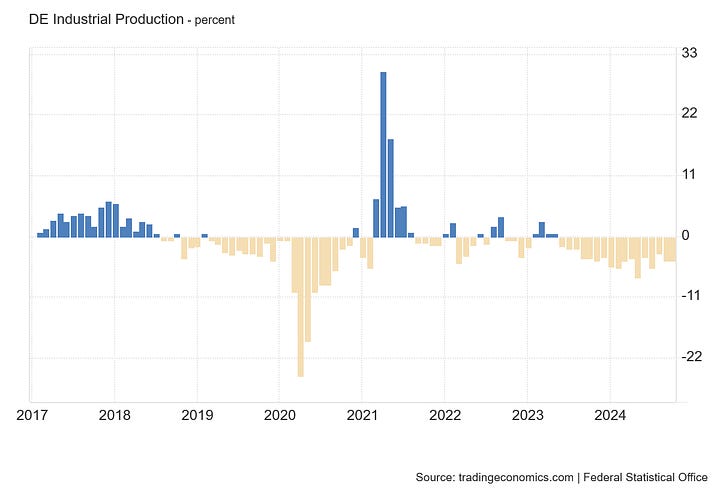

Germany has been by far the biggest casualty in this regard, although the other industrial nations of Europe have not fare at all well as a result of both the war and the sanctions imposed on Russia.

Germany’s industrial output had already been under duress pre-COVID, and the COVID lockdowns had only aggrevated the situation. The war in Ukraine has not helped Germany recover its industrial base.

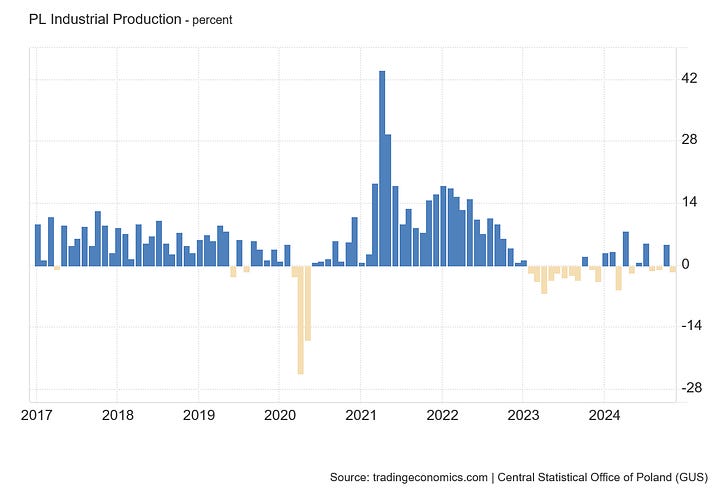

Even Poland, which has been a rising industrial producer in Europe, has seen its output suffer.

Sadly, this outcome was also foreseeable early on in the war, as Europe’s decision to abruptly do without Russia’ energy exports was a body blow to European industry.

What was speculation in 2022 can be fairly answered in the affirmative now at the end of 2024: Europe is unquestionably de-industrializing.

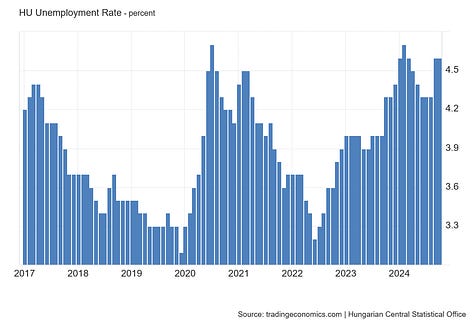

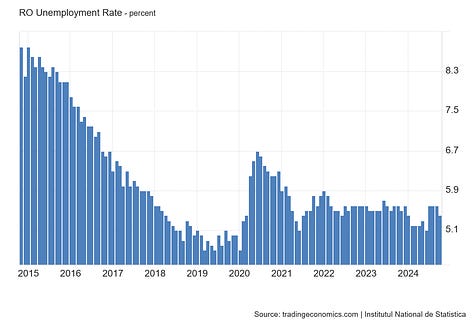

The loss of industrial output has predictably produced a surge of unemployment in several EU countries—Germany most especially.

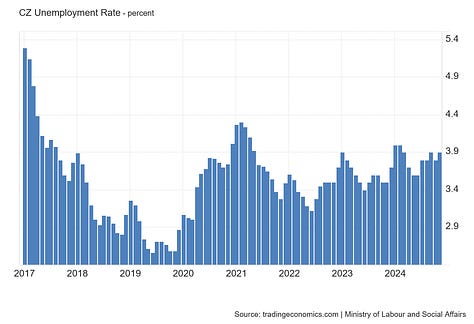

But Germany is far from alone in this: Hungary and the Czech Republic have also suffered in terms of job loss, as has Romania.

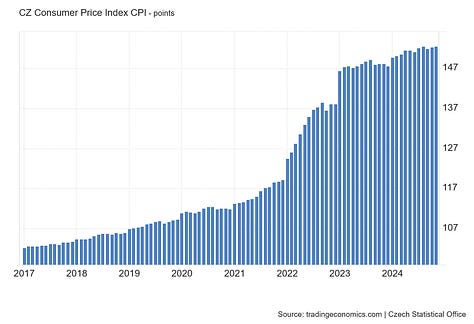

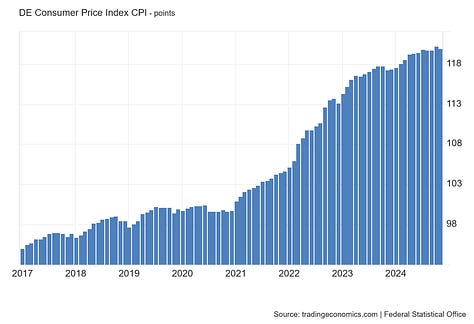

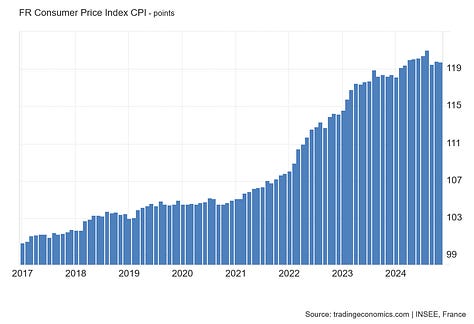

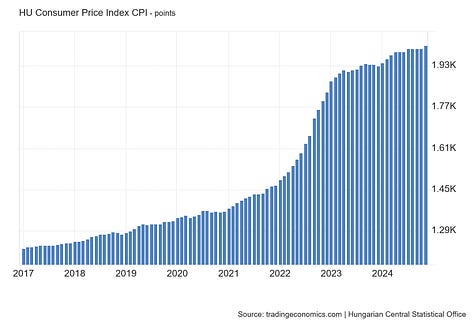

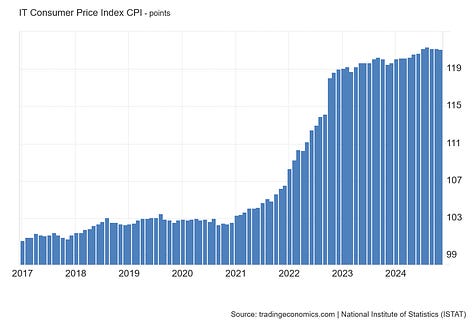

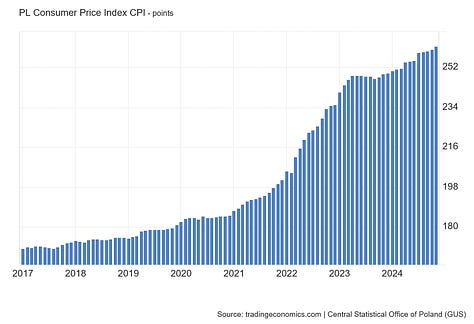

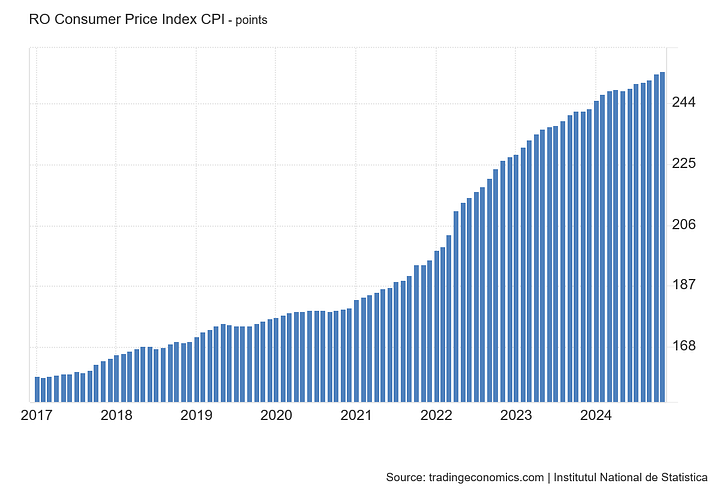

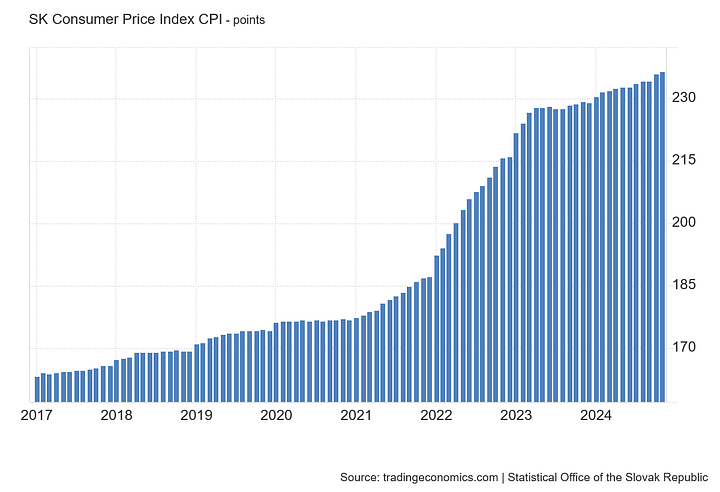

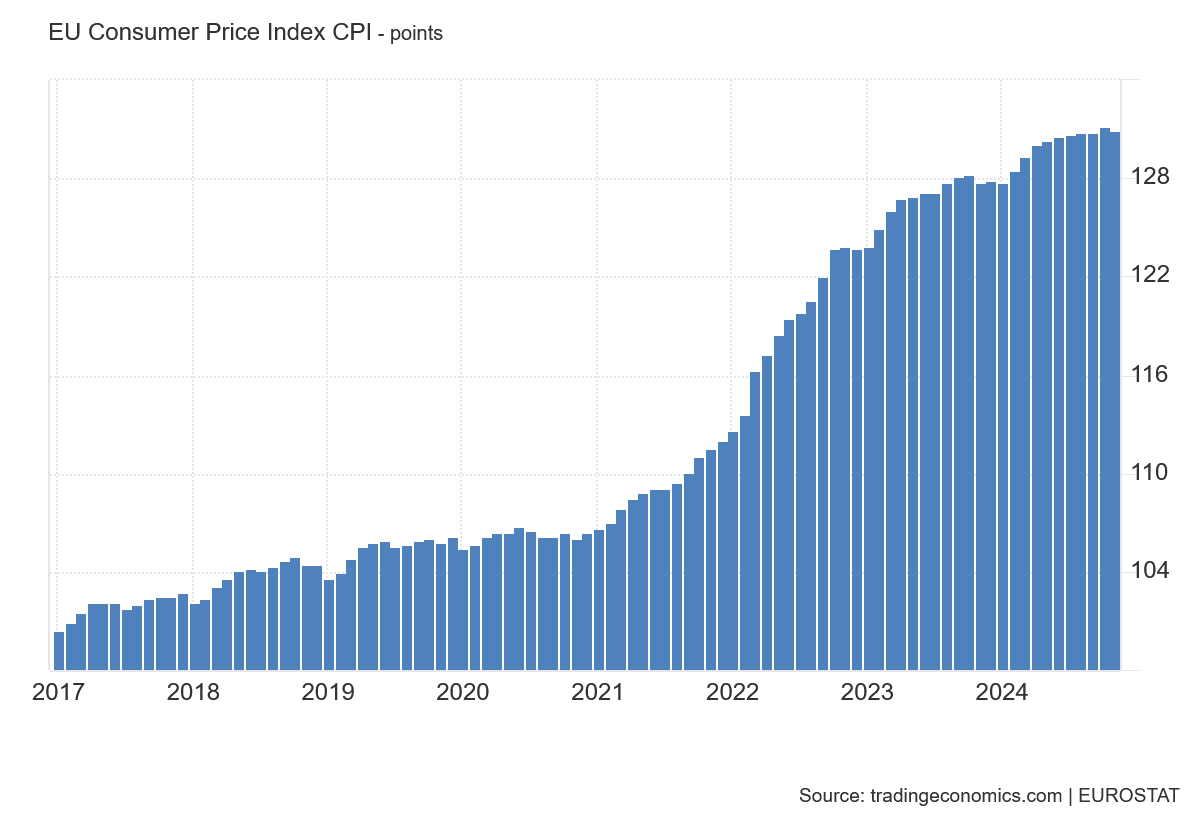

Nor are the costs all on the supply side of the economic equation. Europe’s consumers have also paid a price for the war in Ukraine, in the form of an inflation shock.

Inflation was already ticking up throughout 2021—the inevitable consequence of the COVID Pandemic Panic lunacies—and the war in Ukraine, coupled with the sanctions imposed on Russia, only added fuel to the inflationary fire.

As has been the case on the supply side, no European nation has been spared.

Such are the consequences of suddenly sanctioning a major trading partner. The loss of Russian exports to Europe has made everything in Europe that much more expensive.

The combination of inflation and de-industrialization has also been fairly hard on the euro currency, which had already been somewhat battered by the pandemic. Since the start of 2022, the euro has declined some 8.5% against the dollar.

But for the war and the sanctions, the euro would have not only recovered against the dollar from COVID Pandemic Panic dislocations but would have strengthened.

Job loss, manufacturing loss, inflation, and currency depreciation—Europe’s economic future has dimmed considerably, in direct and foreseeable consequence to the EU decision to sanction Russia over the war in Ukraine. While Ukraine has been waging a brutal war of attrition against Russia, Europe has been waging its own economic war of attrition.

Economic warfare is as bloodless as conventional warfare is bloody, but the consequences to Europe are proving to be just as far reaching. No matter how the war in Ukraine is resolved, Europe’s economic landscape has been forever altered by the war, and not for the better.

Much of the lost industrial production in Europe will not soon be recovered, as that production will have moved overseas. The jobs which have been lost, particularly within industrial sectors, may be lost for good.

Consumer prices once raised rarely decline again. When they do, such deflation often proves more economically painful than inflation.

Inflation and economic slowdowns are going to make the nations of Europe that much more vulnerable to price shocks should Europe find itself one of Trump’s tariff targets when he begins his second term of office next month.

If Donald Trump is not successful in forging a peace in Ukraine once he takes office in January, Europe will soon be compelled to confront the same question Russia already faces: how much national treasure is Europe willing to spend in an economic war with Russia?

Nor can there be any doubt that such spending is very much a choice by Europe. Putin may have chosen to invade Ukraine, and so may be fairly said to have started the conventional war, but Europe and the United States chose to respond with draconian sanctions. Europe alongside the United State chose to participate in an economic war of attrition against Russia.

Every economic impact Europe is feeling because of the war in Ukraine and the sanctions imposed on Russia is something Europe—or at least Europe’s leaders—have chosen.

Has Europe chosen wisely? Can Europe justify the costs it has incurred and will continue to incur because of the sanctions imposed on Russia?

As with Russia, such justification hinges largely on which narrative one embraces regarding the conventional war in Ukraine. If one views the war in Ukraine as the result of militaristic aggression by Vladimir Putin, then perhaps the economic war is a necessary step in order to ensure that Putin does not attempt war with the rest of Europe. If one views the war in Ukraine as a consequence of Europe and NATO recklessly expanding eastward in order to keep Russia “contained”, then the economic contest might seem similarly reckless.

Yet as with Russia, neither narrative has any ultimate bearing on the costs to Europe of the war or the sanctions imposed on Russia. The costs arising from both the war and the sanctions imposed on Russia are being felt by Europe regardless of which narrative framing one applies. The de-industrialization, the job loss, and the inflation arising from the war in Ukraine are the same regardless of why that war is being waged.

As with Russia, Europe will be paying the costs of this war long after the guns finally fall silent and peace is obtained.

Will it have been worth it?

🌐🇪🇺 To live in interesting times.....

....thanx Amigo, all facts matter indeed! ✔️

No, I don’t think the Europeans will think it’s worth it, and they will likely shift political inclinations as a result. We’ve already started to see this in multiple countries. Some of the economic consequences thus far - especially in Germany - have been so severe that political change is almost a certainty, don’t you think?

Thanks for more great data and analysis, Peter. I truly wish you were on staff at the White House.