Yesterday, the EU and G7 nations implemented their phase next of price caps and other sanctions against Russian oil and refined products.

On Friday, EU governments tentatively agreed to set a $100-per-barrel price cap on sales of Russian diesel to coincide with an EU embargo on the fuel. Diplomats representing the 27 EU governments set the cap on Russian diesel fuel, jet fuel and gasoline ahead of a ban taking effect Sunday. It aims to reduce Russia’s income while keeping its diesel flowing to non-Western countries to avoid a global shortage that would send prices and inflation higher.

The $100-per-barrel cap applies to Russian diesel and other fuels that sell for more than the crude oil used to make them. Officials agreed on a $45-per-barrel limit on Russian oil products that sell for less than the price of crude.

The deal follows a similar G-7 agreement to limit the price of Russian crude oil to $60 a barrel. All the price ceilings are enforced by a requirement for the world’s largely Western-based shippers and insurers to abide by sanctions and handle oil products only priced at or below the limits.

Between the price cap on refined products (mainly diesel fuel) and the EU-wide ban on diesel, the EU is taking another direct bite out of Russia’s hydrocarbon revenue streams.

That is, at least, the plan. The question that will soon be answered: What will the impact be?

The refined products price cap comes on the heels of the demonstrably effective crude oil price cap.

It is not unreasonable, therefore, to presume similar effects from the refined products cap. In fact, some analysts argue that the refined products cap could prove even more effective.

The sanctions on refined oil products could prove to be more impactful than the crude oil sanctions, as it is by no means certain Russia will be as successful in finding replacement customers for products such as diesel fuel as it has been in diverting crude shipments from Europe to India and China.

Asia is thirsty for crude. India and China both import huge volumes for their massive refining systems. The two nations took about 14.5 million barrels a day in 2021, and that figure almost certainly increased last year. By contrast, they brought in just 3 million barrels a day of refined products from overseas.

But those huge systems mean that a ready market for Russian refined products outside Europe simply doesn’t exist in the way it did for crude. Many of the newly built plants were designed to maximize the production of diesel, the very fuel for which Russia needs new buyers.

Moreover, while China and India are quite happy to buy Russian oil at steep discounts (and thus have considerable incentive to buy crude below the $60/Bbl price cap), the OECD countries in particular have been quite willing to dispense with Russian oil, as most Asian OECD nations have already largely jettisoned Russian oil as a percentage of their total oil imports.

For its part, Russia’s principal retaliation has already been put in place: banning the sale of oil or refined products to any nation participating in the price cap regime.

According to the plans of Washington and its allies, the price cap policy means prohibiting Western transport companies from transporting Russian oil and oil products to third countries if they are delivered at a price higher than the limit set by the West. Moreover, Western financial institutions are prohibited from insuring such shipments if they are carried out by independent operators. On December 27, 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree on retaliatory measures to the introduction by the West of a price ceiling for Russian oil, banning its supply to buyers who joined this restriction from February. The decree entered into force on February 1, 2023 and is valid until July 1, 2023.

Additionally, Russia’s position is that the price caps are fundamentally unsustainable, owing to the market imbalances they see the caps creating within global oil markets, according to Russian Federation Press Secretary Dimitry Peskov.

"Naturally, this will lead to a further imbalance in international energy markets," Peskov answered a question from journalists about the attitude of European countries towards the embargo on Russian oil products.

However, even Peskov cannot deny the efficacy and durability thus far of the crude oil price cap.

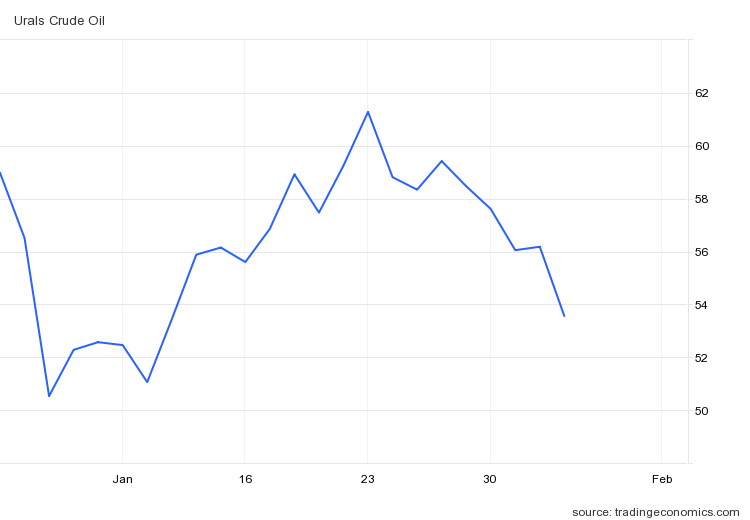

To be clear, questioning the durability of the crude oil cap is not only reasonable, but eminently appropriate, given the recent price history of Urals crude.

However, since I examined that particular issue, the reality of Urals crude pricing is that it has fallen significantly, approaching $53/Bbl as of Friday, February 3.

The lower Urals crude falls below the price cap, the longer the price cap will endure (there can be no challenge to the price cap when the market price is significantly below the cap level).

Certainly, the price for heating oil in Europe has fallen considerably.

The price for gasoil (fuel oil, in other words), has followed a similar trajectory.

The closing price in Europe for both these commodities is as of Friday, February 3rd. The one thing we have not seen is anticipatory price moves due to the refined products cap’s imminent implementation.

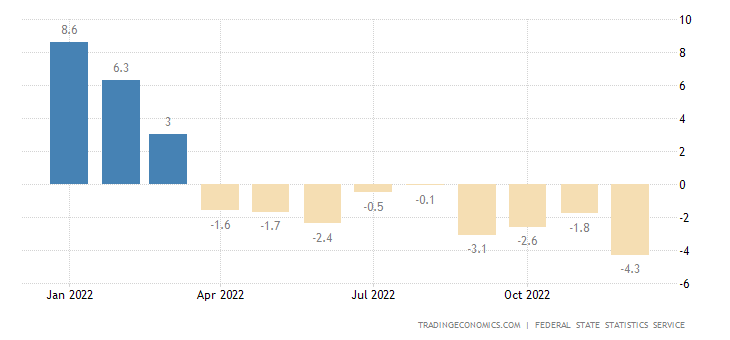

Moreover, Russia’s ability to withstand the revenue shocks is demonstrably decreasing as their economy continues to contract as a result of sanctions and overall economic isolation as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Even before the price caps were implemented, Russia’ crude oil production was down from pre-war levels.

It is difficult to envision production not falling further as a result of the refined products cap, despite Russian bravado to the contrary.

There is no reason to believe that Russia will drastically reduce oil refining or the production of petroleum products in connection with the start of the EU embargo, Russian Energy Minister Nikolai Shulginov told reporters.

"There are no grounds yet to believe that we will drastically reduce the processing or production of petroleum products," Shulginov answered the question of whether the EU embargo on Russian petroleum products threatens the production and processing of oil in Russia.

With industrial output shrinking 4.3% year on year in December, Russia’s internal capacity to fully utilize its own oil production is debatable at best.

With inflation returning to the Russian economy, the resiliency of the Russian consumer is also shrinking, particularly as food price inflation accelerates.

Inflation in Russia from January 24 to 30 accelerated to 0.21% from 0.14% a week earlier, since the beginning of the year consumer prices rose by 0.74%, according to Rosstat .

In the reporting week, the growth in prices for fruits and vegetables accelerated to 3.5% from 3% in the previous week. Including prices for onions rose by 7.8%, cucumbers - by 7.6%, carrots - by 3.4%, tomatoes - by 2.8%, bananas - by 2.3%, potatoes - by 2%, beets - by 1.4%, cabbage - by 1.3%, apples - by 1%.

If the effects on Russian oil revenues from the refined products cap mimics those of the crude oil cap, the impact on the Russian economy is almost certain to be significant. Given that the Russian economy has been shrinking almost since the war began, any such impact is going to be painful.

The impacts to the overall EU economy will depend entirely on the prices for diesel and other fuel oils.

Europe’s manufacturing base has demonstrably contracted as a consequence of the war in Ukraine as well as the sanctions applied against Russia by Europe.

Consumer price inflation, already having risen significantly in Europe throughout 2021, got considerably worse after February of 2022, although inflation has moderated during the fourth quarter.

Unlike Russia, the EU economy has not (yet) officially shown any signs of contraction.

At present, the EU economy is poised to withstand the consequences of the new EU sanctions against Russian refined oil products better than the Russian economy, at least at first. How long that remains the overall state of affairs in Europe is as of yet an open question.

While the price caps have been and likely will be impactful on the Russian economy, it must be acknowledged that the one thing the crude oil cap has not done is dissuade Putin from the path of war regarding Ukraine. Putin is still putting troops in the field, and still attempting to sieze territory in Ukraine. There is precious little reason to believe the refined products cap will have a greater impact on Putin’s determination to continue fighting.

In terms of hastening the war’s end, the crude oil price cap has been a complete failure, as indeed all of the sanctions levied against Russia have been. The refined products cap will not do any better. At most it will make Putin’s war more expensive.

Unfortunately for the rest of the world, a more costly existence in both Russia and Europe has not yet been sufficient incentive for the two sides to seek a pathway to peace.

The only certain outcome of these latest moves in the economic war between Europe and Russia is that the war will continue.

a lot of heavy sweaters and fluffy blankets being deployed in all of those chilly homes