Wall Street Fears What It Knows The Fed Will Try To Do

It Should Fear Why The Fed Can't Succeed

Last week, the 10-Year Treasury note crossed a psychologically important threshold, as perceived by most of Wall Street: the 4% interest mark. Wall Street fears what the Federal Reserve even as yields move past that mark—raise the Federal Funds rate yet again.

Benchmark 10-year Treasury note yields were marked 4 basis points higher on the session at 3.983%, but hit 4.001% earlier in the session, the highest in four months and a level that has been linked to both the start of the stock market's October rally and its fizzingly out in early February.

It should be noted that the 10-Year Treasury note only briefly crossed the 4% threshold, and as of this writing is hovering just below that threshold at 3.97%.

Wall Street’s great fear is that the Fed means to push yields and interest rates even higher, and keep them there. In the prevailing narrative, this will inevitably trigger a recession, regardless of the impact the higher rates have (or don't have) on consumer price inflation.

That the US economy is already in a stagflationary recession is, of course, eternally beyond either Wall Street’s or the Fed’s comprehension.

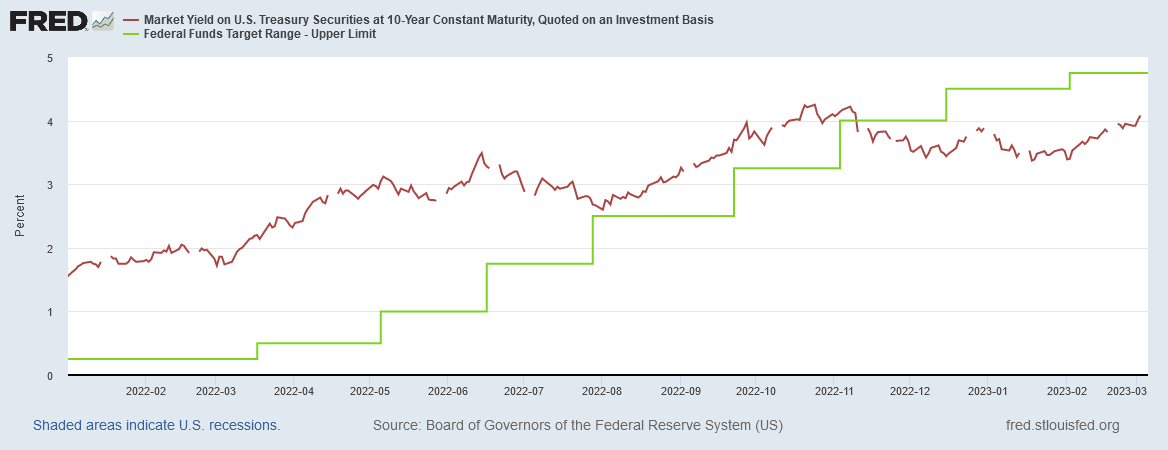

Lost in Wall Street’s usual hyperventilations over the Fed’s rate hikes is that the Fed’s moves have been of problematic efficacy. Increases in the Federal Funds rate are not guaranteed to catalyze increases in the 10-year Treasury yield. The November increase actually led to a decline in the 10-year Treasury yield, which only reversed last month.

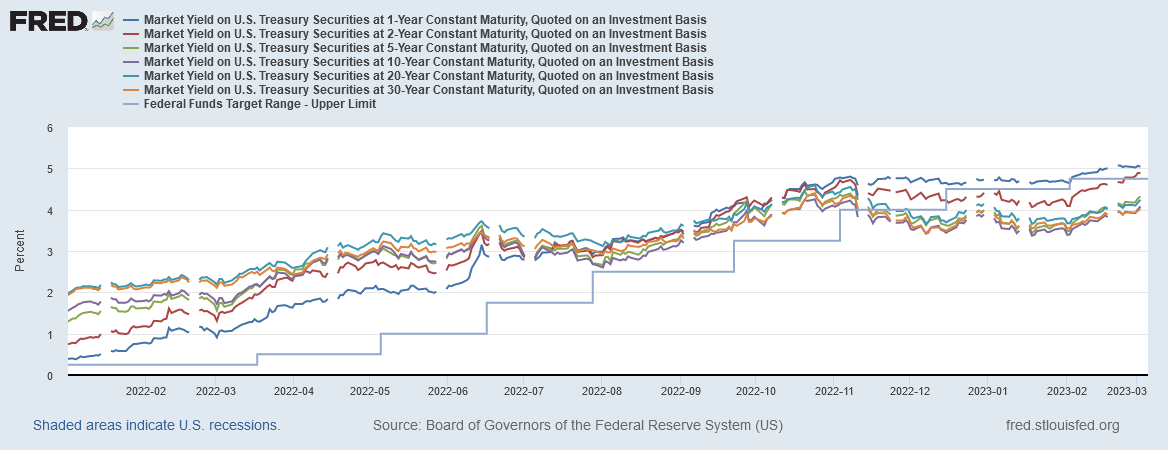

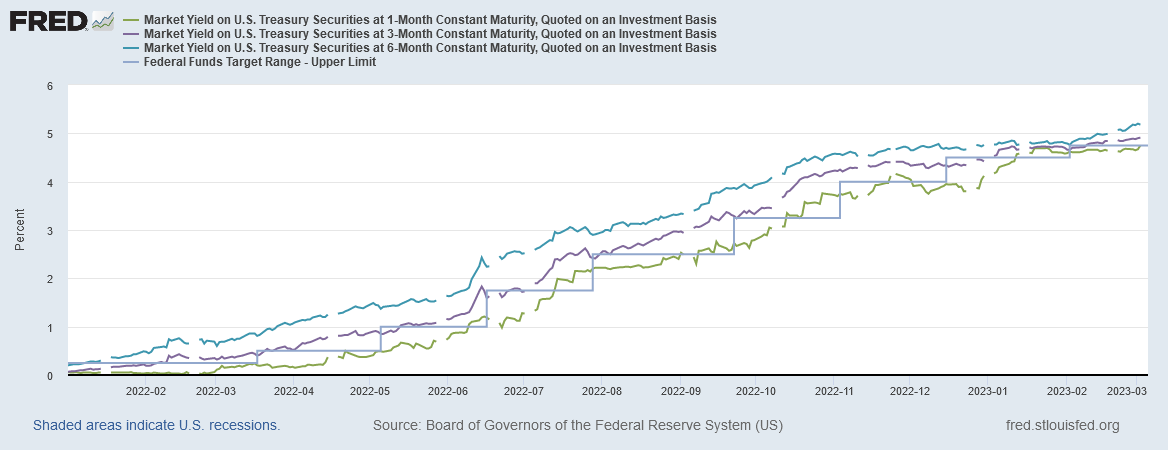

Until the November rate hike, the 10-year Treasury yield was greater than the Federal Funds rate. Ever since that hike, it has been less than the Federal Funds Rate. With the exception of the 1-year Treasury, this pattern occurred across the longer end of the yield curve.

Even the short term yields plateaued in November and only resumed rising shortly after the last increase in the Federal Funds rate.

Hiking the Federal Funds rate alone does not guarantee that other interest rates will rise, nor has it ever guaranteed that.

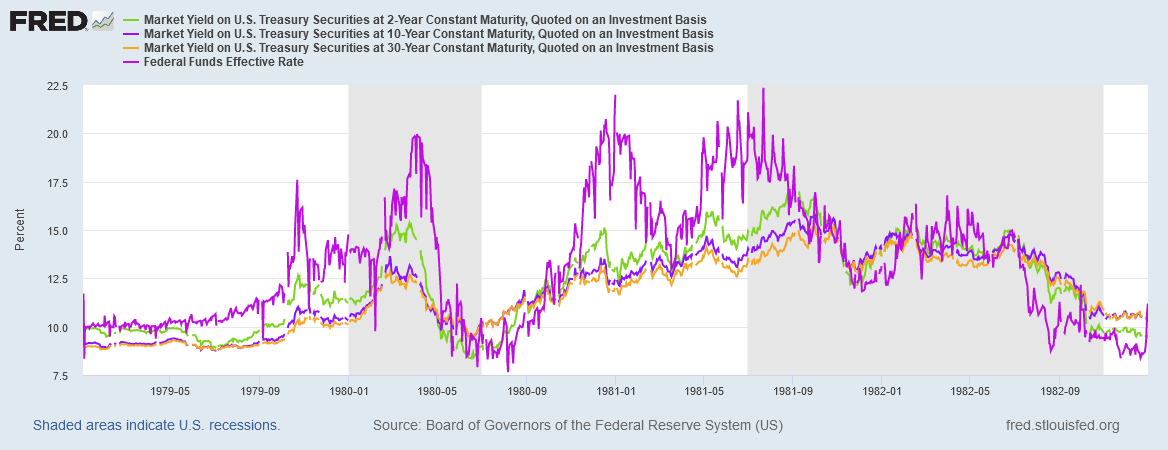

If we look at the Federal Funds rate vs Treasury yields during the Volcker recession era of the early 1980s, we see immediately just how problematic the impact of the Federal Funds rate hikes on other interest rates truly is.

At the points where the Federal Funds rate peaked, the spread between the Federal Funds rate and Treasury yields was at a maximum.

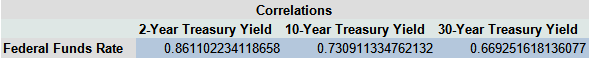

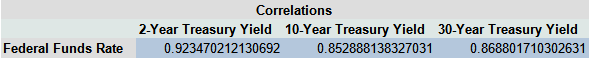

In fact, when we look at the correlations1 between the Federal Funds rate and the 2-Year, 10-Year, and 30-Year Treasury yields during Paul Volcker’s first round of rate hikes, between 9 October 1979 and 22 July 1980, we find a strong correlation, but one that is significantly weaker compared to a period with a lower Federal Funds rate, such as the present period from 1 January 2022 through 2 March 2023.

Then, as now, the ability of the Federal Funds rate to push Treasury yields (and other interest rates by extension) higher became increasingly problematic the higher the rates climbed. Then, as now, there were periods where the Federal Funds rate rose and Treasury yields declined.

It is mildly absurd to speak of the Federal Reserve “raising rates” when their principle lever, the Federal Funds rate, is this uncertain. The Fed raises the Federal Funds rate and prays Treasury yields will follow.

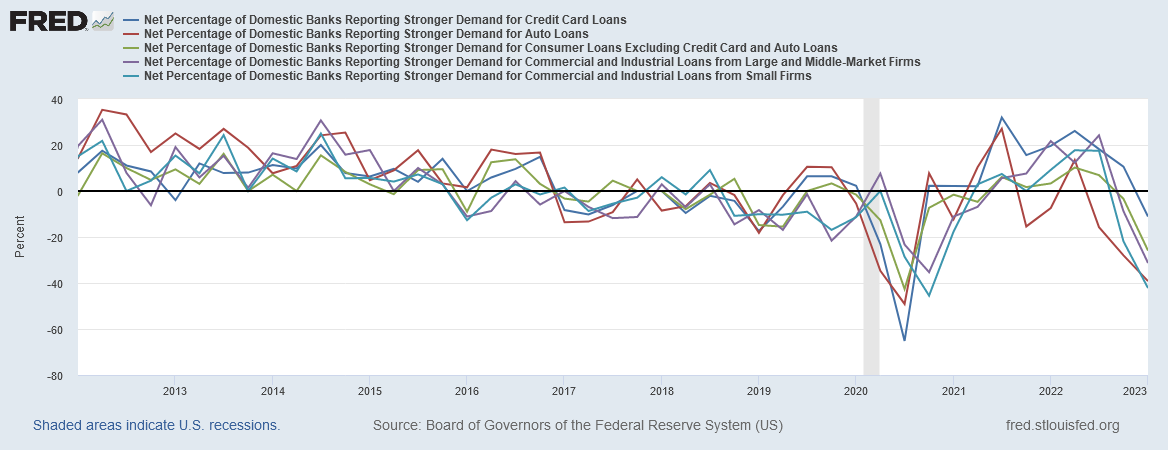

Nor is it hard to fathom why yields aren’t rising in tandem with the Federal Funds rate. When the demand for credit is trending down, interest rates are going to experience significant downward pressure, regardless of the Federal Funds rate—and loan demand has been in decline from 2017 onward, save for a period of correction after the 2020 Pandemic Recession.

Moreover, while loan demand did enjoy a brief gain during 2021 and 2022 before trending down again, even after the 2020 recession the declines in loan demand have outpaced the increases.

It is impossible to effectively push rates any higher if no one wants to borrow.

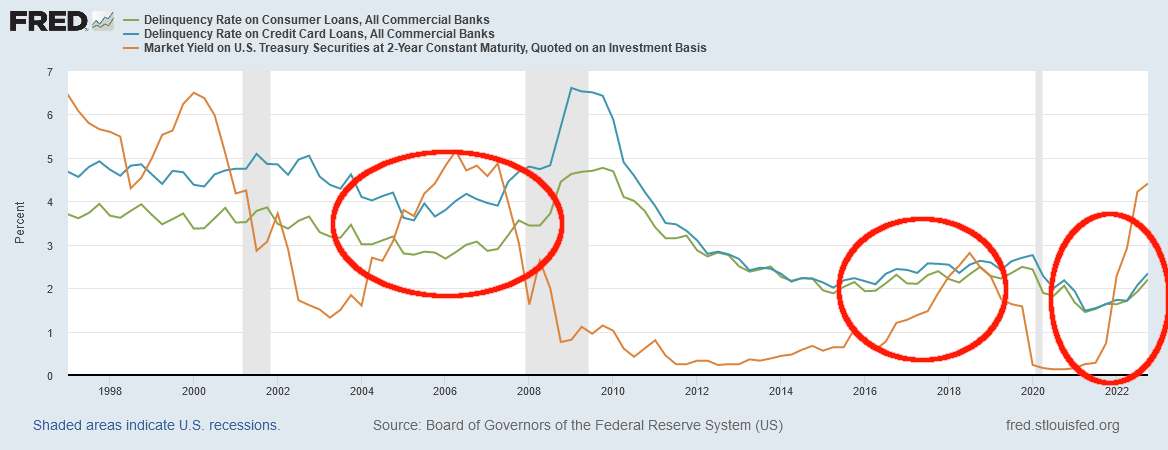

Why has demand declined? One reason has been loan delinquencies, and in particular delinquencies among consumer loans and credit card rather than commercial loans (or even mortgages). People are having more trouble servicing their debt loads, which effectively takes them out of the market for new loans (or greatly increases the cost to them, which is functionally the same thing).

If we look at delinquency rates between consumer loans and credit card loans on the one hand, and the 2-Year Treasury yield on the other, we quickly see that significant rises in yields produces a rise in delinquencies as well.

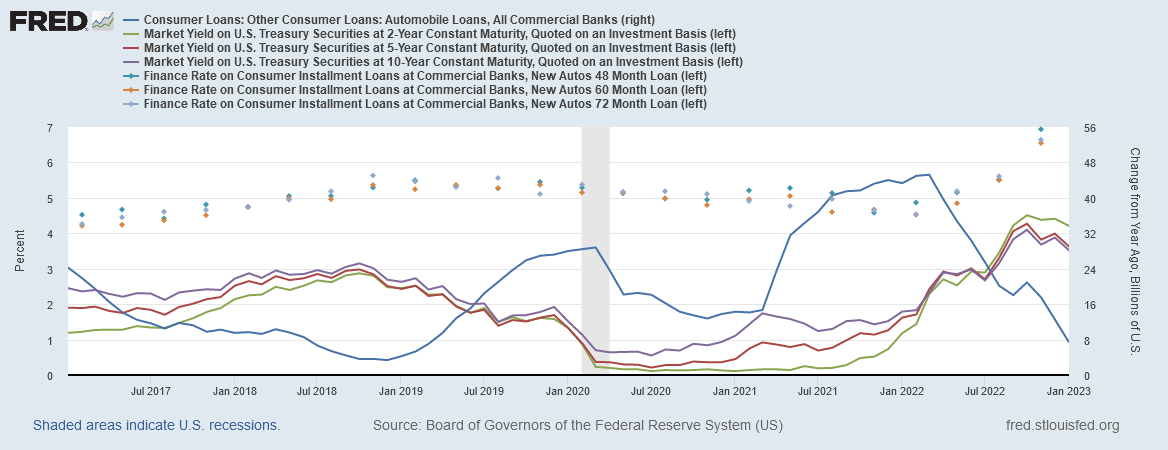

We see a similar pattern play out post-COVID on auto loans.

In the case of auto loans, not only did the amount of new loans year on year drop significantly as interest rates rose, but declining car values plus higher interest rates made new car purchases more problematic, as consumers grapple with being “under water” on their car loans.

The build-up in negative equity — or the amount that debt exceeds a vehicle’s value — is rattling consumers and raising alarms within the industry. Though it’s not unusual for drivers to carry negative equity, some dealers say more people are arriving at their lots up to $10,000 underwater, or “upside down,” on their trade-ins. They’re buying at still-sky-high prices and rolling debt from one car to another and even onto a third. Loans are commonly stretching to seven years.

“As trade-in values begin to cool, each month more and more consumers will find themselves falling from positive to negative equity,” said Ivan Drury, director of insights at auto-market researcher Edmunds. “Unless American car shoppers break their habit of buying again too soon, we’ll see the negative equity tide continue to rise.”

Consumers have a set interest rate on their auto loans for the life of the loan, but their ability to trade in their old car for a newer one is seriously impacted by interest rate rises, among other factors.

We should pause to note that we do not see the same correlation between rates and delinquencies when we are looking at residential mortgages.

This should not surprise us, however, because unless one has an adjustable rate mortgage, once a mortgage is taken out on a house the rate is locked in for the duration of the mortgage, just as with a car loan. Thus rising mortgage rates do not impact existing mortgages, and so do not make servicing that debt more difficult for the existing homeowner.

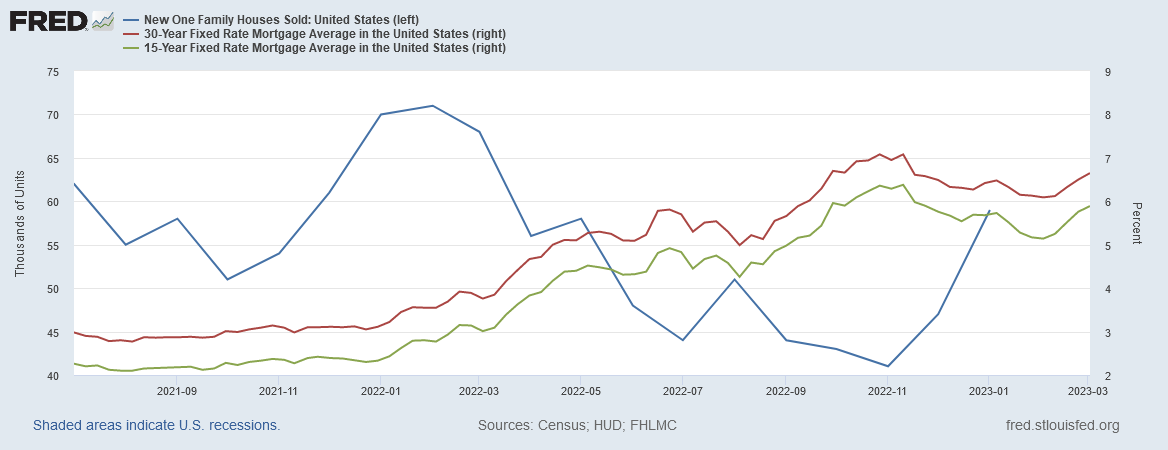

Where interest rates impact mortgages and real estate markets is in sales volume. Home sales were generally rising in the US until rising mortgage rates began pushing them down.

Existing home sales began declining once the 15-year mortgage reached 4.8% and the 30-year mortgage reached 5.7%.

For new home sales the break point was even lower—2.7% for the 15-year mortgage and 3.5% for the 30-year mortgage.

It is also instructive to note that new home sales have picked up in 2023, right at the time that mortgage rates began trending down. Whether that trend can survive the recent uptick in mortgage rates is a question yet to be answered.

While the impact is different depending on the nature of the loan, the end result is the same: rising interest rates reduce demand for loans, which eventually inhibits further interest rate hikes—an eminently predictable outcome when one realizes that interest rates are also the “price” of loans.

Wall Street displayed more of its economic illiteracy when it chided the Federal Reserve for thinking that rising mortgage rates might help further the cause of bringing down inflation by arguing this exact same point.

More than 40% of all US mortgages were originated in 2020 or 2021, when the pandemic drove borrowing costs to historic lows and triggered a refinancing boom, according to data from Black Knight.

That’s good news for all the homeowners who locked in cheap loans — but maybe not so great for the Federal Reserve, as it seeks to cool the economy by raising interest rates.

Yes, existing mortages already have “locked in” their interest rate. What rising interest rates do is inhibit future mortgage originations, and thus future home sales, which has already had a depressive effect on average home prices.

Interest rates are economically impactful where they impact consumption, and in real estate markets that means at the point of housing purchase. Rising interest rates serve to dissuade potential home buyers, thereby creating downward pressure on housing prices.

This behavior of interest rates also helps illustrate why recession is not merely a potential consequence of the Fed’s rate hiking strategy, but a necessary element of that strategy.

By pushing interest rates up, the Federal Reserve makes credit less accessible at all levels. Credit card debt becomes more costly, as do other types of debt. Mortgage rates make home purchases that much more expensive, and prohibitively so as rates move higher.

Given the centrality of consumer credit to the US consumption-based economy, rising rates and rising credit delinquencies mean less consumption—i.e., a deeper recession. That is inevitable when consumers fund a growing portion of their expenditures with debt rather than income.

How did consumers fund this spike in Personal Consumption Expenditures? Most likely with credit card debt. That is the obvious conclusion to be drawn from the fact that the monthly percentage change in credit card debt very nearly matches the surge in Personal Consumption Expenditures at 1.8%.

Note that growth in credit card debt has exceeded the month on month change in personal consumption expenditures every month except December for the past year. Americans are funding more and more of their consumption with debt instead of with income—which also means that, contrary to the BEA’s assessment, Americans also aren’t saving as much as the BEA claims.

Strangling credit-based consumption is, of course, what the Fed has said it would do all along.

The Fed is going to strangle consumption, and keep strangling so long as there is any hint of positive economic news in the US. That was fundamentally the position staked out by Jay Powell last year at Jackson Hole.

We should hardly express surprise or much dismay at the Fed doing what it said it was going to do.

The hitch in the Fed’s grand strategy to rein in consumer price inflation is that, ultimately, interest rates will not cooperate. They did not cooperate during the Volcker Recessions and they are not cooperating now. The Fed can (and will) keep pushing the Federal Funds rate higher, but with diminishing impact to Treasury yields and related rates. We have already seen interest rates decline even at elevated Federal Funds rate levels. Should loan demand continue to contract, we will see interest rates retreat once more.

Already, even though interest rates have largely risen throughout February, the 1-Year and 2-Year Treasuries are showing signs of having reached a plateau after about February 21, and the 10-Year and 30-Year Treasuries are potentially not far behind.

The Federal Funds rate is at 4.75%, and will soon be at or above 5%, yet the 10-Year and 30-Year Treasury yields have yet to sustain above 4%.

Wall Street might be fearful of interest rates moving north of 4%, but where Wall Street’s great risk lies is in the forces that are pushing interest rates south of 4%, and preventing that threshold from being persistently breached. Loan delinquencies and collapsing loan demand are capping interest rates far below where the Fed wants them to be.

As more loans become delinquent, and as fewer new loans are originated to take the place of the “bad” loans, the more likely it is that something will trigger another liquidity crisis just as what happened in the 2007-2008 Great Financial Crisis2, when rising interest rates catalyzed first a series of mortgage defaults and then a series of bank liquidity crises that spread around the globe. The liquidity crunch might not come in real estate, but with rising delinquency and default rates, the probability that it will come is also rising.

So far, Wall Street is ignoring that probability, and that means exposure to the risk is not being mitigated or hedged in the slightest. That’s never a good sign for anything.

Wall Street is worried about the Fed hiking interest rates. Wall Street ought to be worried about why the Fed very likely cannot hike interest rates as much as they would like.

Correlation calculations were performed using the statistical functions of LibreOffice Calc v7.4.0.3.

Singh, M. “The 2007–2008 Financial Crisis in Review”. Investopedia. 18 Sept. 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/09/financial-crisis-review.asp.

Yes, valid points and reasoning - thanks for this!

When ‘stagflation’ hit in the 70s, it was partially ‘solved’ by ‘inflating the debt away’. (Some would say that, in the larger picture, problems were just kicked further down the road.) Do you think the same tactics - inflating the debt away - would still work to get us out of stagflation? Ever since we started ‘quantitative easing’ in 2009, it’s all become so convoluted that I don’t know what the prevailing cause-and-effects would be about any of it anymore...

Great article. Summary: nobody is in the mood to borrow.

How quickly a mood change comes about (and stabilizes) is the $64K question.