Oil prices are rising again, and for reasons (hopes?) that sound vaguely familiar: China demand for oil is soon to accelerate, this time because of an upcoming holiday travel period.

In the mid-Monday North American session, WTI crude oil prices continued to climb, trading at $78.78 per barrel, marking a gain of 1.13%. The price has pierced the 20 and 50-day Exponential Moving Averages (EMAs), indicating bullish momentum, with buyers now setting their sights on the $80.00 per barrel mark.

Growing optimism that China’s May Day holiday will increase travel and fuel demand boosted the market. Booking for overseas trips for the May Day holiday continued to recover, but numbers remain far from reaching pre-Covid levels. Although oil prices jumped, the uneven economic recovery in China from the Covid-19 pandemic keeps oil prices fluctuating.

Taken at face value, this is a reasonable prediction. An increase in air travel means an increase in aviation fuel consumption, which means an increase in aviation fuel demand, which means an increase in aviation fuel production, which means an increase in crude oil demand. This prediction may even be spot on. China's economy may very well power an increase in global oil demand and lift up global oil prices.

However, we have heard predictions about higher oil prices before, and few (if any) of them have come true recently. Why should this one be any different?

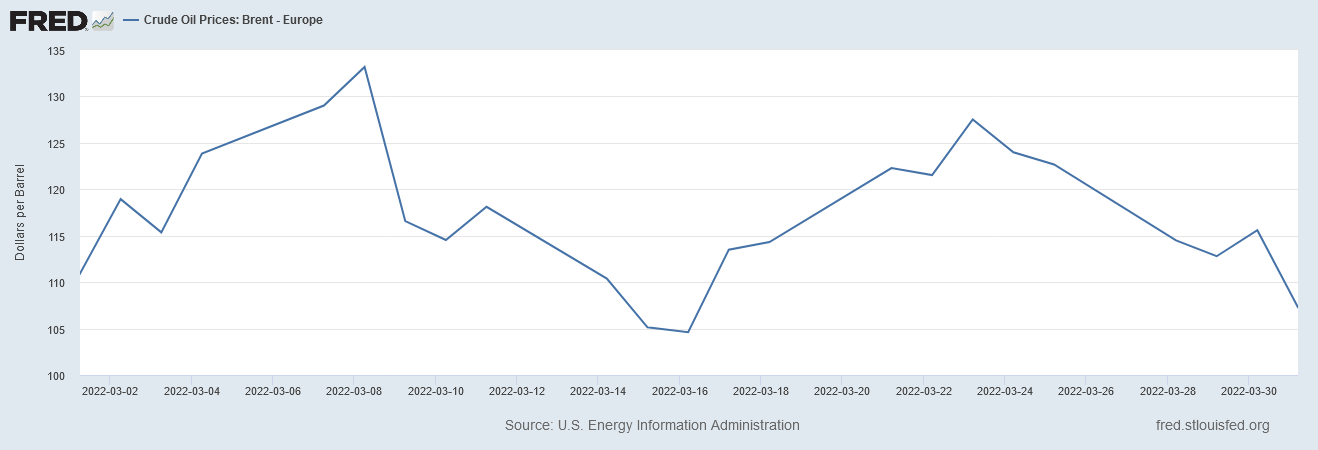

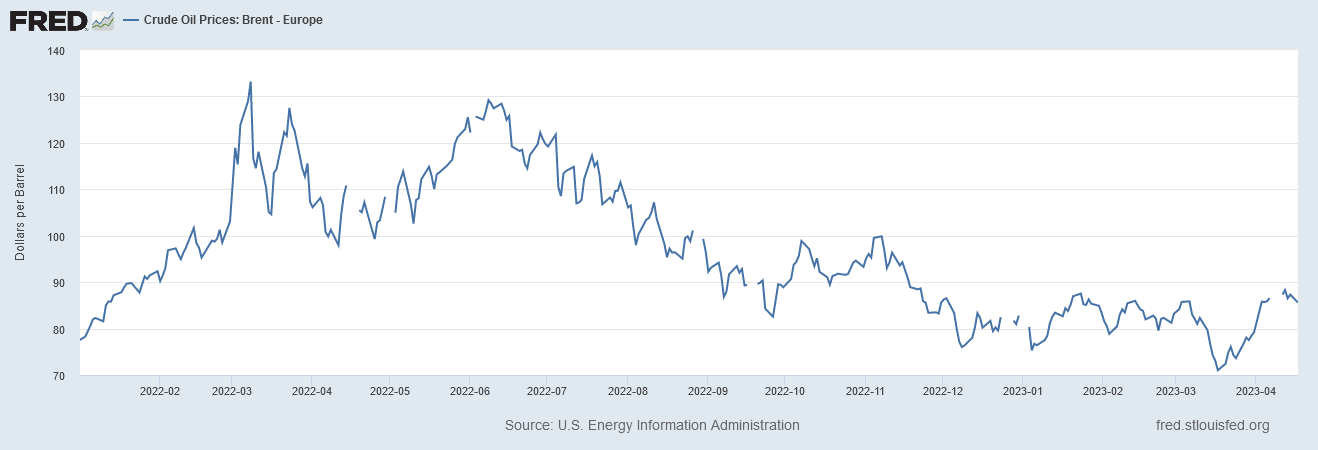

We do well to remember that, in the immediate aftermath of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, oil market analysts were projecting that oil would go as high as $200/bbl in March of last year.

Traders piled into options that oil could surge even further after rising to the highest since 2008, with some even placing low-cost bets that futures will rise above $200 before the end of March.

Prices to buy call options for higher crude prices surged Monday as the market assessed the possibility of a supply cut-off from Russia, one of the world’s biggest exporters. At least 200 contracts for the option to buy May Brent futures at $200 a barrel traded on Monday, according to ICE Futures Europe data. The options expire March 28, three days before the contract settles. The price to buy them jumped 152% to $2.39 a barrel.

By the end of March, the price of Brent Crude had fallen by more than $15/bbl.

West Texas Intermediate had posted similar declines. Anyone betting on the price of oil going even higher from there lost bigly.

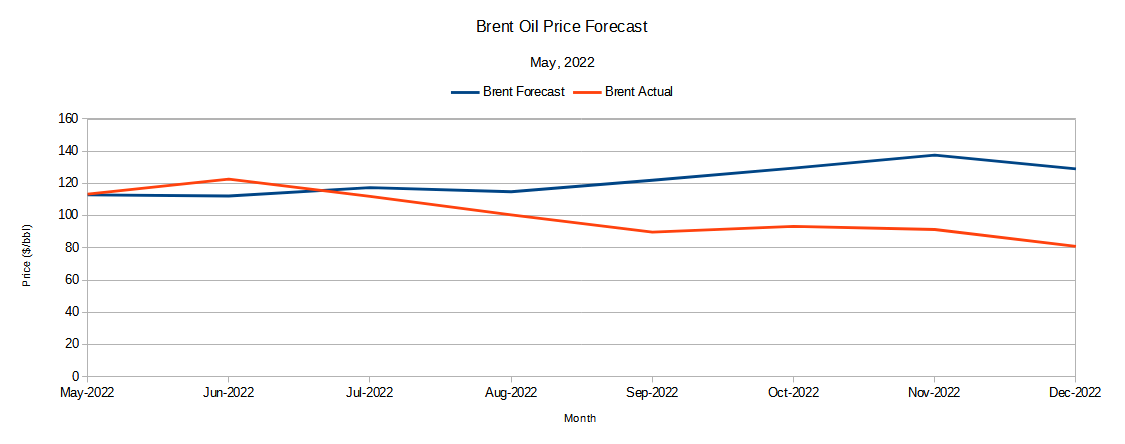

In May of 2022, the Economy Forecast Agency called for Brent Crude to be priced at $129.01/bbl by December of that year. Price data gathered by the US Energy Information Administration showed Brent Crude at $82.82/bbl.

This, too, would have been a bet on rising oil prices that would have lost bigly.

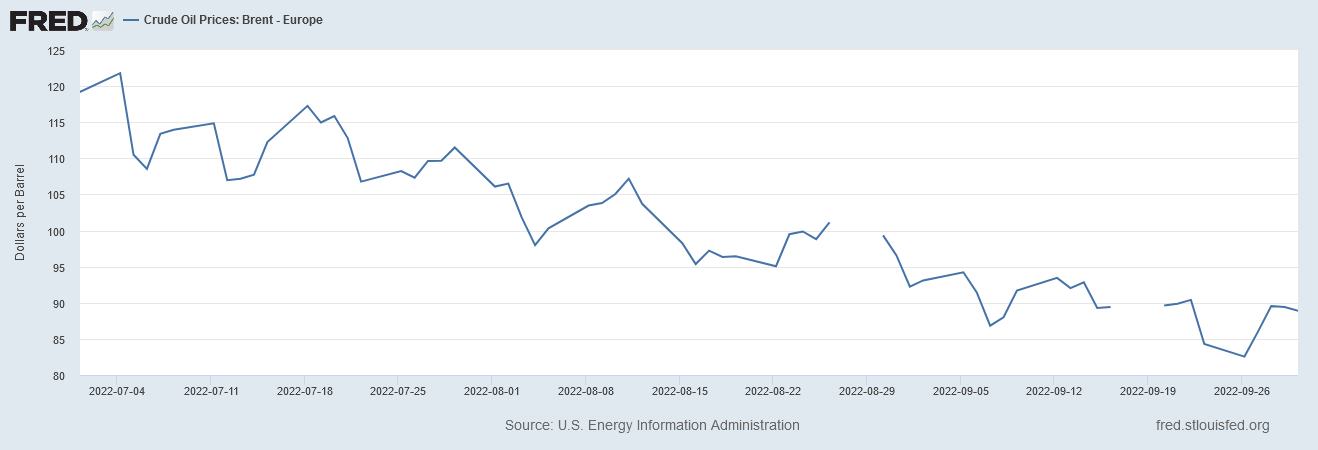

Flash forward to June 7 of last year, when Goldman Sachs predicted oil would hit $140/bbl between July and September, 2022.

High oil and gasoline prices will need to rise even higher this summer to incentivize new production and discourage consumption, according to Goldman Sachs.

The Wall Street bank is now forecasting Brent crude oil prices will average $140 a barrel between July and September, up from its prior call of $125 a barrel. Brent is currently trading at about $120 a barrel.

By September 30, 2022, the price of Brent Crude had fallen from $120/bbl to $83/bbl.

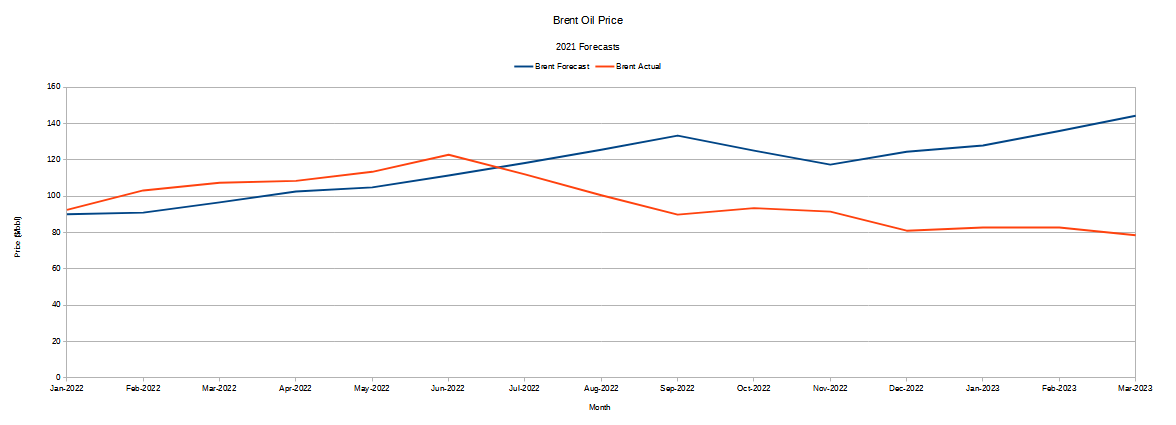

From the perspective of October, 2021, oil prices were seen as trending upward for the foreseeable future, according to a forecast by the Economy Forecast Agency. Actual oil prices as recorded by the EIA tell a far different tale.

How have the prognosticators been so consistently unlucky? Not only have they gotten the magnitude of oil price changes wrong, but the direction as well. They forecast the price of oil going up, and it goes down.

One possible reason oil demand forecasts are well wide of the mark is they reflect a certain amount of bias on the part of the analyst, that may or may not be taking into account all relevant data.

For example, in forecasting a rise in aviation fuel demand in China for the upcoming holiday travel period, some analysts are leaning heavily on a presumption that, with Zero COVID policies no longer in effect, Chinese travelers are going to return to their status quo ante travel patterns.

Some 170 million Chinese holidayed abroad in 2019, before the pandemic struck. That figure sank to less than 9 million last year at the height of China’s lockdowns. The likelihood of dramatically more air travel explains why jet fuel consumption in China is widely seen as the single biggest driver of world oil demand growth this year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

The signs are encouraging. Overseas ticket searches for Golden Week are 120% of the level in 2019, state media reported, citing an estimate from Trip.com. As of April 18, actual bookings were more than 10 times that of last year, the Securities Daily reported.

“Mainland China’s domestic jet fuel demand has almost fully recovered, while international jet fuel demand has recovered to close to 70% of pre-Covid levels,” said Fenglei Shi, a director covering Chinese oil markets at S&P Global Commodity Insights. As such, it’s possible that Golden Week could mark a near-complete recovery in China’s total consumption of the fuel, she said.

While the removal of Zero COVID travel restrictions will almost certainly produce an increase in Chinese travelers over last year, a full return to 2019 levels or beyond may contain a measure of wishful thinking. Recent years travel data suggest a somewhat different pattern of travel than from 2019 or earlier.

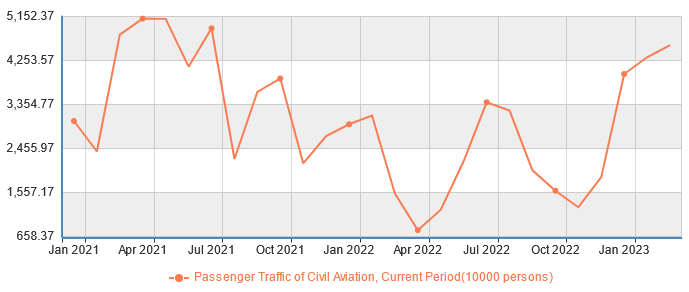

In particular, 2021 only saw a marginal increase in Chinese air travel over March during April and May, while in 2022 Chinese air travel plummeted (this was the time frame of the horror show known as the Shanghai lockdown).

It is also instructive to note that air travel in early 2022 within China dropped by more than half. So steep was the decline that a 10x increase in airline bookings from last year arguably doesn’t translate into a significant month-on-month increase from March, and it is the latter that would drive significant change in oil prices, not the former.

While it is not unreasonable to expect an increase in Chinese air travel, expecting travel to increase by as much as an order of magnitude is perhaps a generous interpretation of ticket search and bookings data. Given that the March 2023 air travel data is, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, below that for March 2021, expecting a ginormous surge in air travel for the 2023 “Golden Week” might prove wildly optimistic. Ticket search data and similar statistics may be indicative of a base desire for travel, but comparisons between far more than just a few months or years would be needed to build valid extrapolations from that data.

At the same time, with respect to China, it is important to consider as well the degree to which the overall economy is actually rebounding from Zero COVID. Economic recovery is contingent upon far more than simply relaxing Zero COVID restrictions, and if the actual recovery is lagging, then that also may dampen any anticipated surge in holiday travel, thus reducing the expected increase in aviation fuel (and thus crude oil) demand.

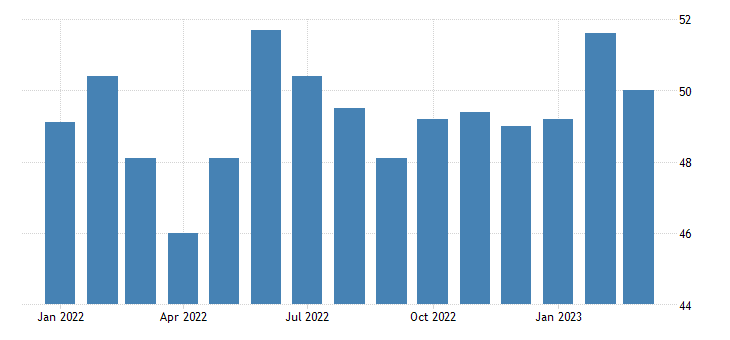

With the various service PMIs for China showing only moderate increases in February and March, after an initial surge in January following the removal of Zero COVID restrictions, there may be a number of economic variables inhibiting a surge in holiday travel, even if people in China have a desire to travel during the upcoming holiday period.

Nor is it prudent to overlook the myriad of problems existing in the Chinese economy, all of which cut against even China’s own claims of economic rebound and recovery.

We can tell from all of these things taken together that China’s economic “rebound” is, as has become de rigueur for the media, more a matter of narrative fiction than of empirical fact. We can tell just from the existence of this data that China has more than its share of economic problems

A constant caveat whenever employing a presumption of “all else being equal” is that, in reality, all else is rarely equal.

As earlier oil price forecasts demonstrate, an expansion in one part of the global economy is easily offset by contraction elsewhere—and there are more than a few indicators of contraction in oil demand outside of Chinese air travel.

One should not overlook the fact that China’s own manufacturing base is still struggling to get back on its feet after Zero COVID, as indicated by the sharp drop in the Caixin manufacturing PMI last month.

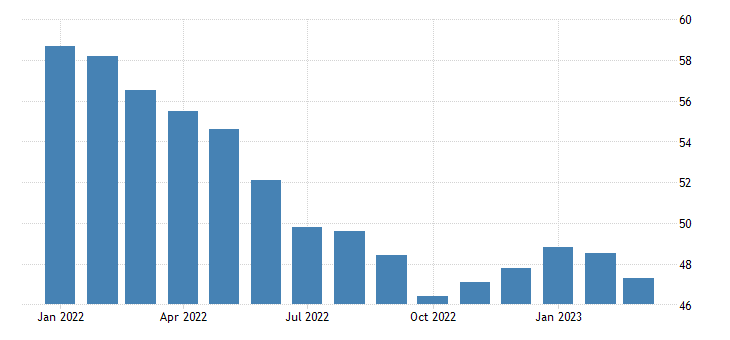

Nor should one overlook the reality of Europe’s own struggles with manufacturing, which has been in steady decline since the beginning of 2022.

Faltering manufacturing activity is invariably going to reduce overall demand for energy, and thus, for crude oil.

As a result, even if there is a strong surge in air travel in China, and thus a surge in aviation fuel demand producing a surge in crude oil demand, any such increase in demand in China to a degree will be offset by probable decreases in demand elsewhere. It is even possible that demand increases in China will be more than offset by demand decreases in the rest of the world.

Global commodity prices are always going to be driven by global demand. Regional fluctuations in demand can only impact global prices if a regional fluctuation is significantly larger in relative magnitude than similar demand elsewhere. In order for an increase in Chinese oil demand to exert upward pressure on oil prices, there has to be no countervailing decrease in European oil demand. In order for an increase in Chinese aviation fuel demand to produce an increase on crude oil demand, there have to be no countervailing decreases in either aviation fuel demand or crude oil demand.

One only need look at the long term trend in Brent Crude prices to see that there have been considerable countervailing decreases in crude oil demand since prices peaked last June.

These downward pressures on global oil prices are certain to mitigate much of the upward pressures China’s upcoming holiday period might place.

The numerous oil price forecasts which have ended up wide of the mark are at a minimum a caution against blithely accepting the corporate media narratives about the state of either the US economy or the global economy (or, indeed, any other nation’s economy). They are also a none-too-subtle reminder of just how wrong “experts” can be about anything.

There likely will be an increase in air travel in China during their upcoming holiday period. It may even be enough to push oil prices up globally for at least a time—or it may not. It may be completely counteracted by a decline in oil demand elsewhere. It might even be counteracted by an OPEC+ nation not abiding by the cartel’s production quotas.

The degree to which many recent oil price forecasts have shot wide of the mark is yet another proof that we should never take at face value any prediction or prophecy of what “will be”, particularly in economic matters. The assessments of analysts and “experts” on anything are only of value if subsequent events validate their predictions.

Ultimately, all “experts” should be approached with the same degree of skepticism one typically reserves for the local weatherman, if only because, like the weatherman, they are quite often completely and totally wrong.

The real problem is that these “experts,” who are usually wrong, have much influence in making over-reaching economic and energy policies. Their justification is always that they are wiser than the markets.

I am getting ready to start union negotiations with the commonwealth of Massachusetts. I’m in this union by virtue of my position and somehow was nominated to represent my office. This issue is one that I hope resonates with the state. Energy prices in my town are absolutely crazy. Everyone is concerned. Where other than here (my #1 stop on substack) should I look for ammunition to back up my arguments? Amazing how behind my wealthy state is on pay scales for its own employees.