One of the ongoing challenges in assessing economic data is keeping a real world focus throughout.

It is very easy to get lost in the nuances of consumer price inflation, “core” consumer price inflation, mortgage rates, credit card rates, and corporate debt limits. It is equally easy to lose sight of the reality of what higher interest rates mean—it costs more to borrow, and it costs more consume as a direct consequence.

However, when Dementia Joe’s handlers attempt a bit of braggadocio about building the economy “from the middle out and the bottom up”, we must pause and dissect the some of the metrics with a bit more attention paid to perspective.

As much as the current regime wants to brand “Bidenomics” in a good way, the realities put on display by the data are not quite so kind to the concept. Put simply, Bidenomics is hurting the very people it purports to help.

The key bragging point of Bidenomics at the moment is the “3 percent inflation” trope.

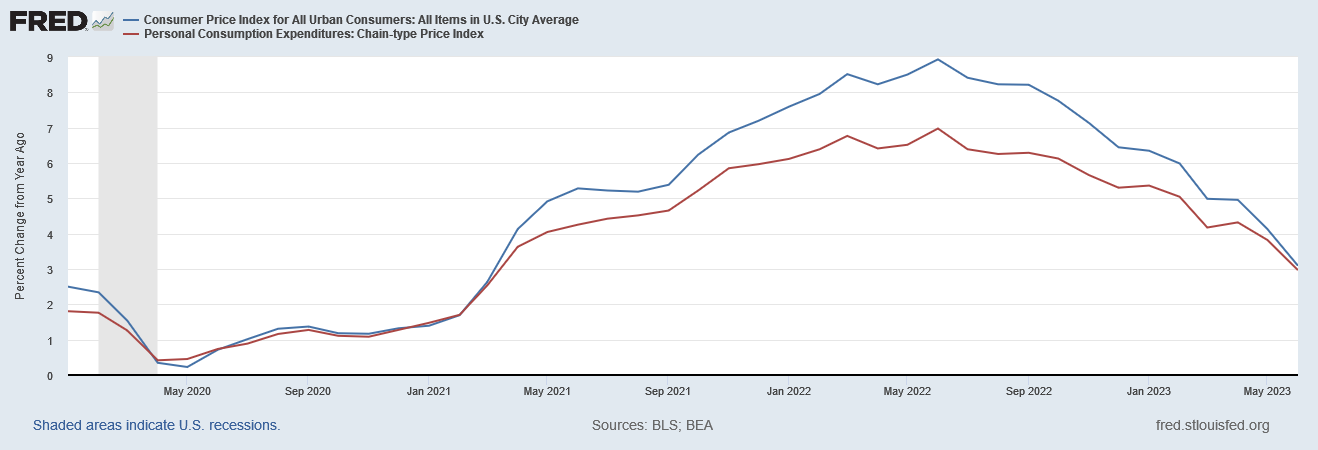

What this means, of course, is that headline consumer price inflation in the US has, according to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, retreated from its recent high of 9%+ to 3% as of June. However, as we have already seen, it is disingenuous to speak of this disinflationary trend as being the equivalent of prices coming down, when all it really means is that they are simply rising more slowly.

After having seen consumer price inflation in this country flirt with double digits, a month where inflation prints at 3% year on year is undeniably a good thing. 3% overall consumer price inflation is a vast improvement over 9.1% year on year.

Even core inflation at 4.8% year on year is a notable improvement, particularly as it breaks core inflation out of the range in which it had been bound for well over a year.

Yet this improvement does not alter the reality that we have significantly higher prices today than just three years ago. It does not alter the reality that we are paying more for food, on average. It does not spare us the purchasing power squeeze that arises when rising prices outpace rising wages.

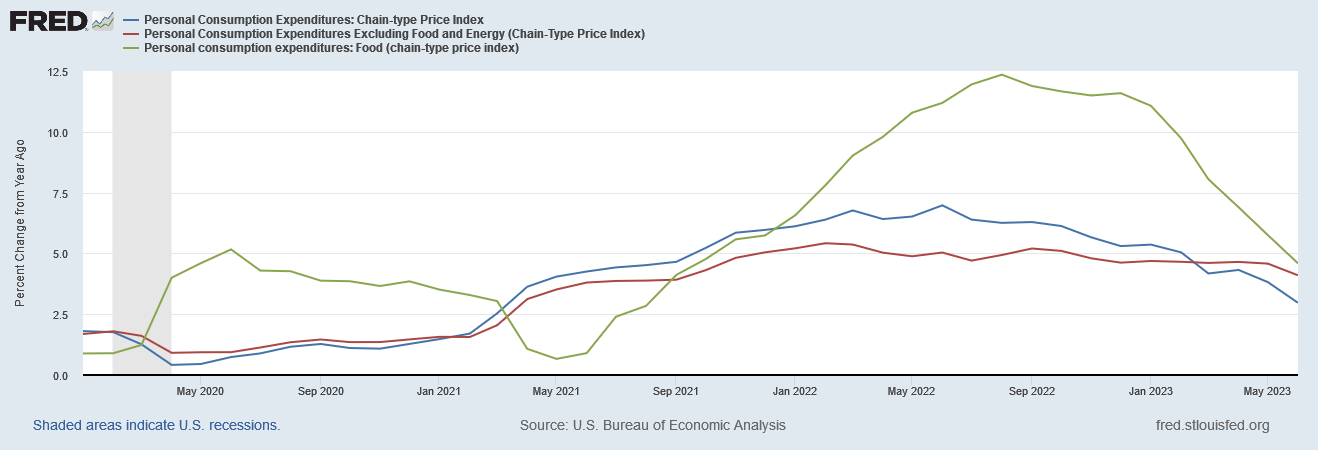

To be sure, it is a good thing that consumer price inflation is down—and it is down not only according to the Consumer Price Index but also by the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index.

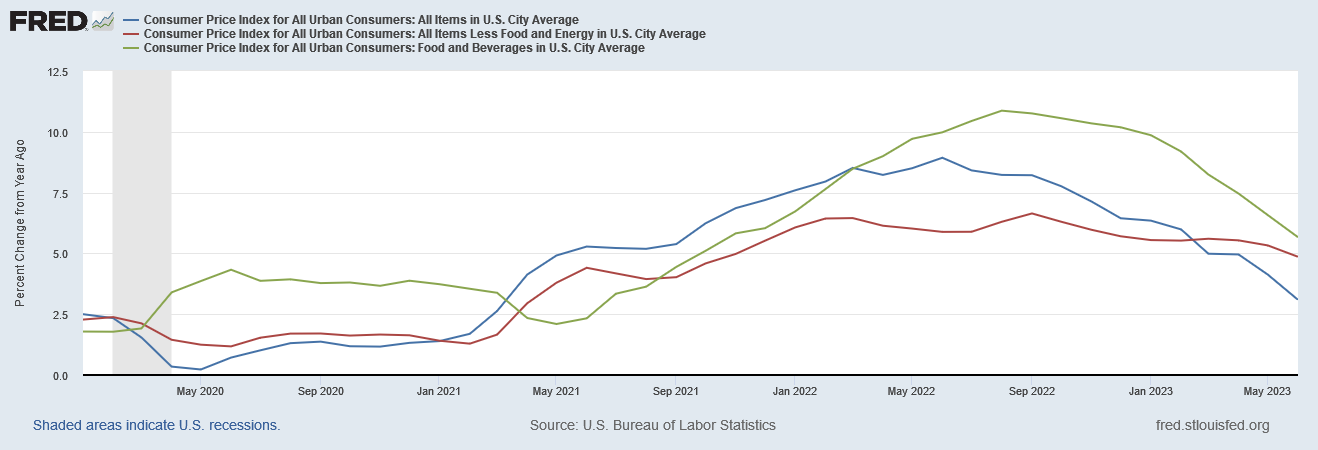

As we have discussed before, this seemingly good trend overlooks the reality that “core” inflation (consumer price inflation with the more volatile food and energy components excluded), has been far more stubborn about returning to the 2% range.

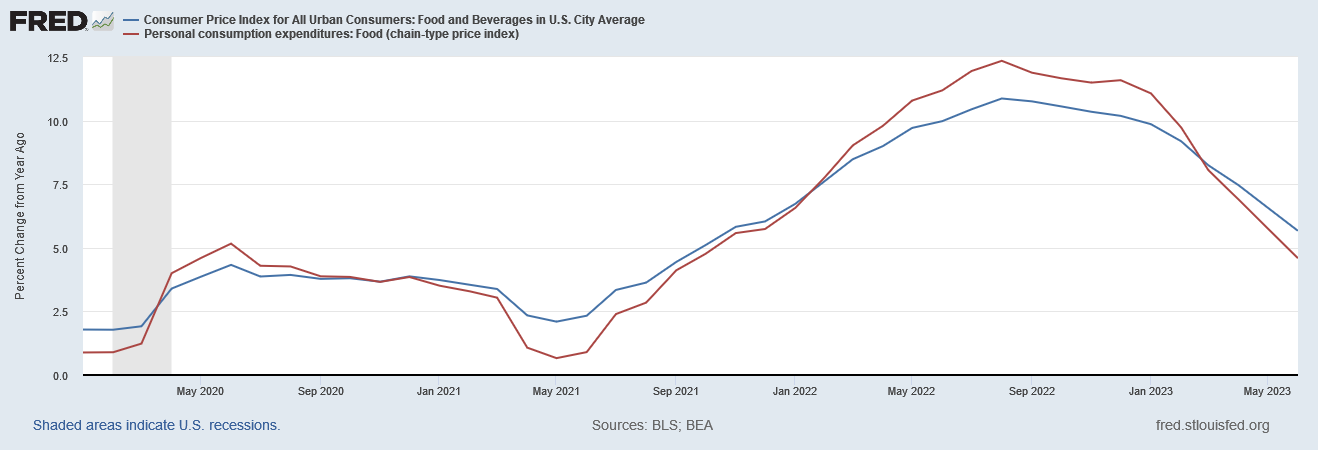

Additionally, while the economists at the Federal Reserve find it procedurally convenient to exclude food price inflation from their assessment of inflationary pressures in the economy, that does not eliminate the reality that food price inflation has been more severe than headline inflation, and is still more severe than even core inflation.

By either set of indices, food price inflation has been a major economic problem in this country.

Moreover, by either set of indices, food price inflation remains significantly more troublesome than either headline inflation or even core inflation.

Per the CPI, food price inflation is more than 2.5 percentage points higher than headline inflation and 0.8 percentage points higher than core inflation.

Per the PCEPI, food price inflation is nearly 2 percentage points higher than headline inflation, and 1.1 percentage points higher than core inflation.

Bidenomics makes no mention of these realities, and would prefer you did not notice them.

There are other inflation pressures as well that are obscured by the headline numbers.

For the better part of the eighteen months between January, 2021, and June, 2022, the price of a used vehicle spiked by as much as 44%, before tipping into outright deflation last November.

New car prices as measured in the CPI, and durable goods as measured by the PCEPI, also saw inflation in the double digits, and price inflation on new cars is still a percentage point and a half above headline inflation.

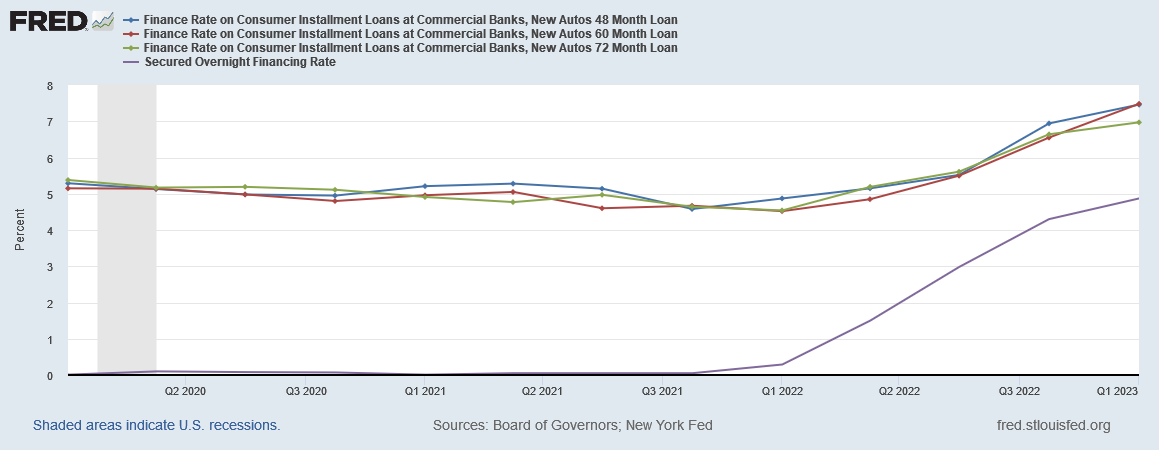

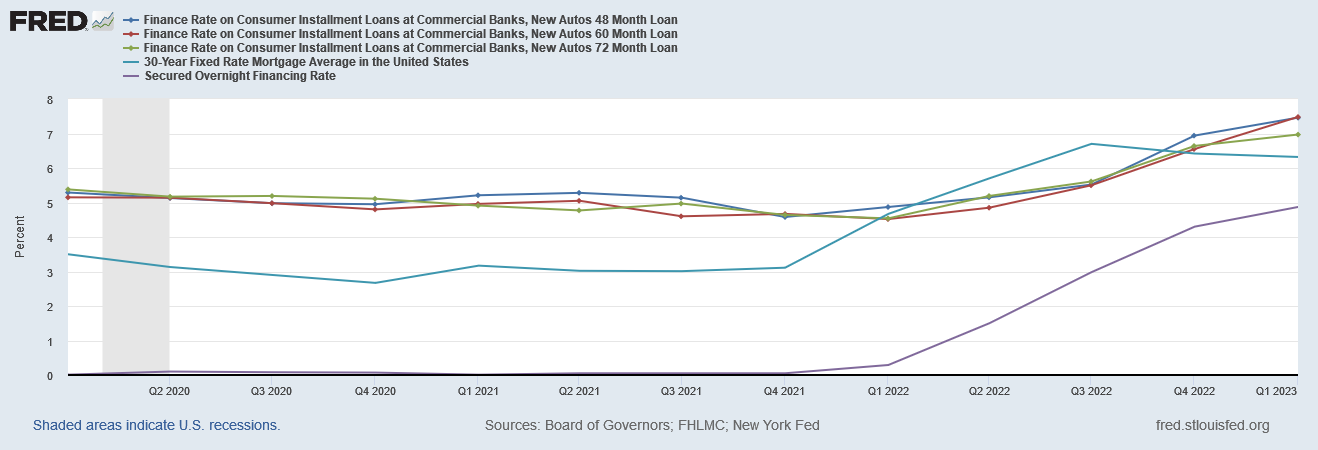

One reason for the easing in vehicle prices, however, has been the reality that the interest rates on car loans have risen significantly—as much as 3 percentage points since the first quarter of 2022.

Although there has been some resistance, auto loans have been one of the few interest rates that have proved responsive to the Fed’s obsessive increases of the federal funds rate, although the federal funds rate is showing diminishing influence even over car loans.

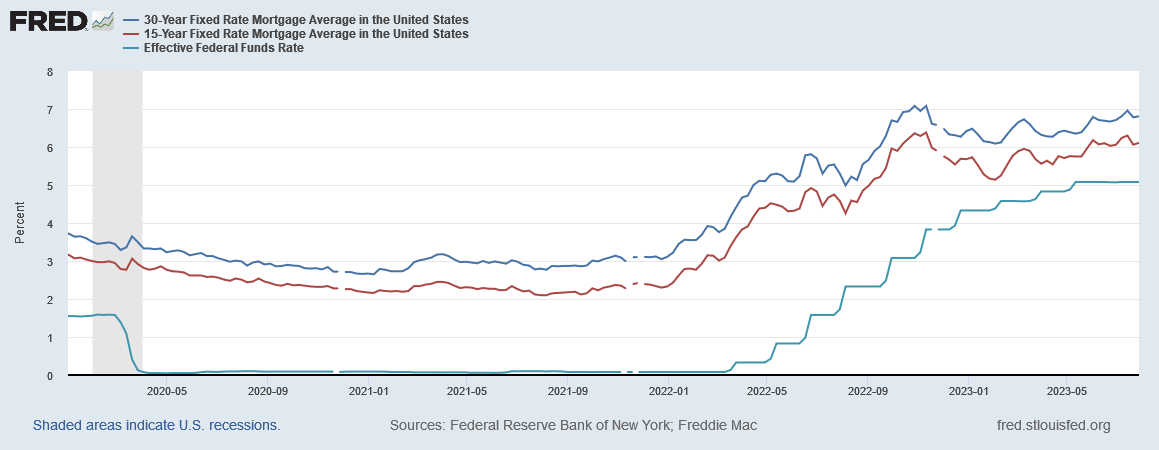

It is a measure of the problematic influence of the federal funds rate that, for the middle part of 2022, a thirty year mortgage had a higher interest rate than a car loan, when it has historically enjoyed a lower interest rate.

Mortgage rates themselves, readers will recall, have become largely immune from federal funds rate pressures once peaking just above 7%.

The one other significant interest rate that has proven to still be sensitive to the federal funds rate has been credit card interest rates, which have risen more than 5.5 percentage points since the first quarter of 2022.

Unsurprisingly, while delinquency rates for mortgages have declined since shortly after the Pandemic Panic Recession, deliquency rates on Other Consumer Loans (principally car loans) and credit cards have risen as the corresponding interest rates have risen.

The one type of debt the Federal Reserve has succeeded in making more expensive has been consumer debt.

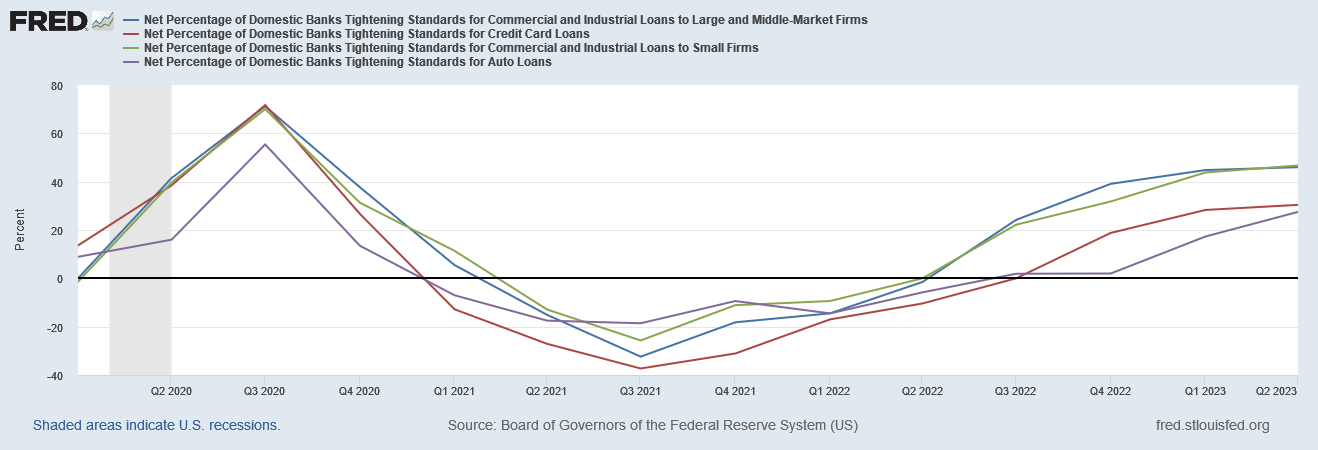

Nor have banks been immune to the consequences of the increasing costs for consumer debt. Since before the first quarter of 2022, banks responding to the Federal Reserve’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) have reported tightening credit standards for consumer loans across the board.

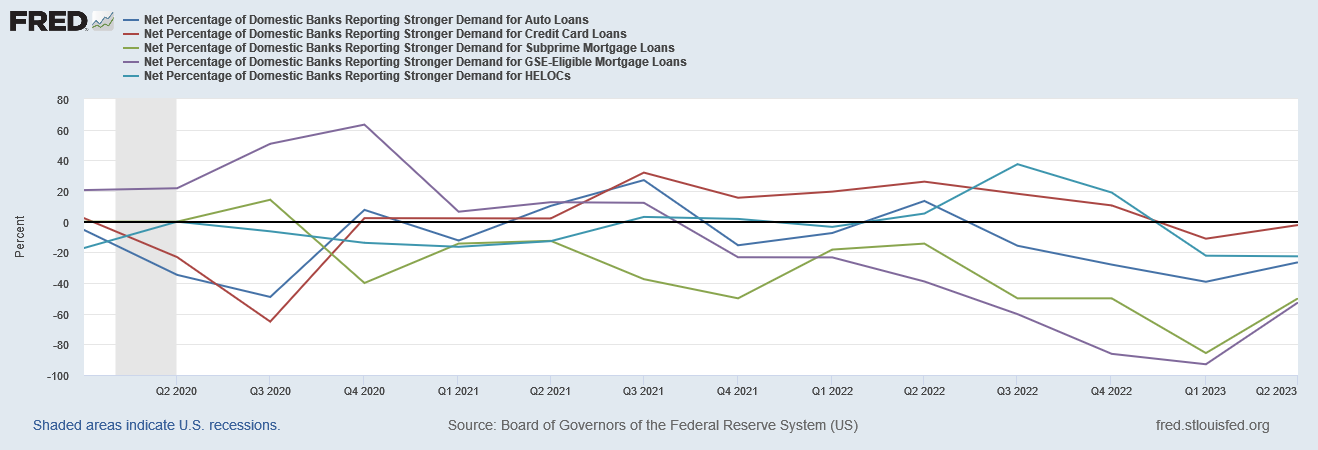

Fewer consumers qualify for credit cards, qualify for car loans, and qualify for various mortgages and home equity loans.

Predictably, this has translated into less demand for credit cards, car loans, mortgages, and home equity loans.

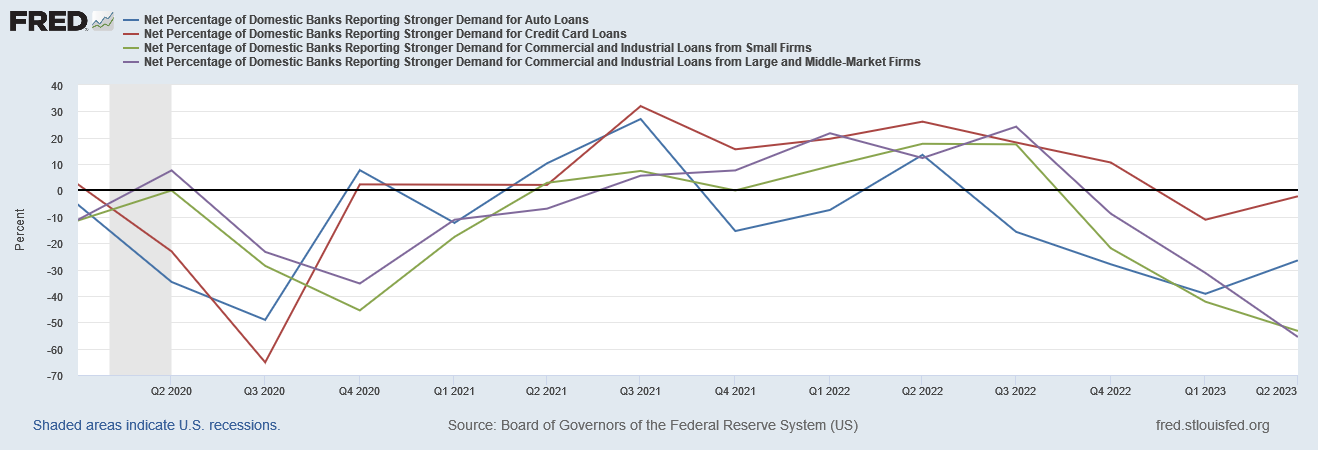

We begin to see the imbalance of this when we compare the degree to which banks are tightening standards for consumer loans vs commercial loans.

It has become more difficult to get consumer credit than it has to get commercial credit, tilting the financial landscape very much in favor of businesses.

Intriguingly, this has not led to stronger demand for commercial loans. While consumer loan demand is very much on the decline, there is still more consumer loan demand than there is commercial loan demand.

Longtime readers know I have frequently pointed out the anti-consumer, anti-worker bias of the Federal Reserve.

The failure of the Federal Reserve to acknowledge the ramifications of wealth inequality played a pivotal role in unleashing the rapid rises in consumer price inflation we have seen since the Pandemic Panic Recession.

Additionally, the Federal Reserve has made it plain all along that recession—and in particular increased unemployment and diminished wages—were the primary elements of their strategy to tame consumer price inflation.

Not to be outdone in efforts to burden ordinary folk with the economic sins of Wall Street, we should not forget that Congress gleefully joined in by depriving railroad workers of their civil liberties last December, forcing them to accept a contract they had already rejected.

The end result has been that the Fed’s rate hikes have fallen almost entirely on America’s consumers, and not on America’s commercial interests. Main Street is being tasked with cleaning up the economic sins of Wall Street—and then is being presented with the bill.

When I assess the impact of the Fed’s rate hikes, I typically focus on Treasury yields; the dynamic nature of government as well as corporate debt, with debt yields that are reported daily, make Treasury yields by far the best bellwether for gauging the proximate impact of increases to the federal funds rate. They reveal clearly and quickly the degree of influence the Fed’s machinations are currently having over interest rates and financial markets.

However, this does not mean that there is no consumer impact from the Fed’s actions. Whether we are looking at reduced credit availability for consumers, reduced loan demand by consumers, or simply reduced demand and consumption of items such as new and used cars, the one thing that remains abundantly clear when we examine the data is that the bulk of the burdens of higher interest rates, tighter credit, and reduced credit availability fall not on commercial interests, but on consumers.

The data makes this much crystal clear: “Bidenomics” translates into ordinary English as “screw the little guy.” No amount of spin-doctoring by corporate media in defense of Bidenomics can conceal its anti-worker, anti-consumer agenda.

That’s the “success” Dementia Joe’s handlers love to tweet out.

Thank you, the cognitive dissonance with life on Main Street (reality) is difficult. I hope people listening to the mainstream will see that promoting inflation down, jobs up, etc has no basis in reality, it’s like living on 2 different planets. Even discussing these things with family is getting more difficult, it used to just be Covid-related but now it’s every topic. There is no critical thinking or openness to discussing with a desire to understand different viewpoints. Very thankful for your articles.

Privatize the profits, socialize the losses.

Will it ever end?