Inflation, Wealth Inequality, And Money Velocity

Why The Fed's Approach Has Fallen Short

Shoutout to subscriber Paula Adams for providing the hook for this latest discussion on inflation.

I still feel like the ship is sinking, even if people on the top deck are having a party.

She’s not wrong.

A recurring theme in this Substack has been the fundamental distortions and economic iniquities highlighted by rampant consumer price inflation. Even before Powell launched his failed rate hike strategy on inflation, I’ve presented hard data on how distorted and unbalanced the US economy has become.

What Paula’s observation points out, however, is that consumer price inflation is not merely a spotlight on economic inequity. Rather, it has been, to a large degree, caused by economic inequity.

To understand how this is the case, we must first look back at the decade before COVID, and some of the unheralded impacts of the Fed’s “quantitative easing” programs after the 2007-2009 Great Financial Crisis and recession.

One of the more remarkable aspects of the Fed’s foray into money printing back then was the conspicuous lack of rampant consumer price inflation that followed—a seeming contradiction to Milton Friedman’s classic dictum that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”1

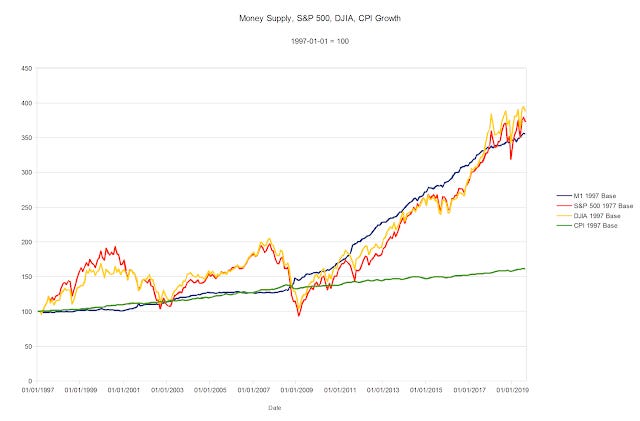

Closer inspection of financial data before and after the GFC yields the explanation: the increased money supply did not produce consumer price inflation in the larger economy because it began driving (and has continued to drive) asset price inflation on Wall Street.

Money which historically circulated out into the wider economy instead remained on Wall Street, where it chased asset prices higher instead of chasing consumer goods and services prices higher. When money is not circulating on Main Street, there’s not going to be much consumer price inflation.

Even economist John Williams’ alternate inflation gauges on ShadowStats do not show a spike in consumer price inflation as a result of the Federal Reserve’s first forays into QE.

Thus even post-2008, we see that, broadly speaking, Friedman’s dictum holds true, and that if we follow Deep Throat’s advice from All The President’s Men and “follow the money”2, we can begin to see how and why consumer price inflation returned with a vengeance in 2021.

It all comes down to the velocity of money.

At first glance, there does not seem to be a reliable relationship between consumer price inflation and monetary velocity. Comparing year on year inflation per the Consumer Price Index and Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index to shifts in M2 money velocity indexed to January of 1990, there is not a discernible correlation between inflation and money velocity.

If we look at the year on year percentage change in M2 money velocity, however, we begin to see some similarities in the movements.

To be sure, it is not a strong correlation, nor a precise one, but rises and falls in money velocity do line up with rises and falls in consumer price inflation. This is something that we should expect to see, as Friedman specifically identifies money velocity as influential in driving inflation3.

This phenomenon of prices changing by more than the difference between the change in output and the change in money stock is often observed and is not special to these particular periods in India. The reason is not far to seek. When prices are going down, money becomes a more desirable way in which to hold assets; its value is increasing day by day; hence people have a strong tendency, if they expect the price decline to continue, to hold a larger fraction of their wealth in the form of money. On the other side of the picture, when prices are going up, money becomes a less desirable form in which to hold assets. In consequence, people tend to economise on their money balances; velocity tends to increase. How much velocity will change depends on whether the fall in prices or the rise in prices is anticipated. Generally, when inflation has started after a period of roughly stable prices, people initially do not expect prices to continue rising. They regard the price rise as temporary and expect prices to fall later on. In consequence, they have tended to increase their monetary holdings and the price rise has been less than the rise in the stock of money. Then as people gradually become wise to what is going on, they tend to re-adjust their holdings. Prices then rise more than in proportion to the stock of money. Eventually people come to expect roughly what is happening and prices rise in proportion to the stock of money.

Thus, following Friedman’s theory, we should not look for a precise correlation between monetary velocity and inflation, merely influence. If money velocity rises,we should expect to see inflation rise. If money velocity falls, we should expect to see inflation fall.

Since 2020, we do see these sort of signals between M2 money velocity and inflation.

As before, the relationship is not a perfect one, but we see enough to presume some influence of money velocity in driving up prices.

At the same time, must also acknowledge the rising wealth disparity between those at the very top of the economic strata and those at the very bottom.

Not everyone is getting as rich as fast—and the richer are getting richer faster. We can see proof of that when we index the wealth data again to January, 1990.

The top percentiles (i.e., the wealthiest) have seen their wealth grow as a greater percentage of their wealth level in 1990, and the bottom percentiles have seen the least percentage increase. During the Great Financial Crisis the lower economic strata lost up to half of their 1990 wealth, while the top tiers retained more than three times their 1990 wealth.

Put simply, the rich got richer and the poor got poorer.

Post 2008, the rate of wealth increase rose for the lowest economic strata—they have had the highest rate of increase, in fact—but the top-most percentiles are right behind them, with the middle brackets lagging behind.

Note: this is not to say that wealth inequality magically resolved itself over the past 10 years. It hasn’t. These are relative increases in wealth, with the lower economic strata enjoying a faster relative increase, but still at a low absolute level as shown in the first wealth chart above.

We see this trend continue post-COVID, albeit with a muted differential between the wealth cohorts.

The result of these differing rates of wealth increase has been a gradual but persistent shifting of wealth to the upper economic strata.

Note that these shifts have occurred across both Democratic and Republican Presidential administrations. Note also that this data is courtesy of the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) system—these are the data sets the government has been recording about the economy. We may safely presume that the whole of Washington DC is either blissfully unaware of these wealth trends or blithely unconcerned about them. I leave it to the reader to decide which is the greater economic mismanagement sin.

This shift in wealth away from the lower economic strata to the higher, coupled with the relative increase in the rate of wealth accumulation by the lower economic strata, helped set the stage for the return of consumer price inflation.

Pre-2008, money velocity relative to wealth cohort showed a marked decline for the lowest cohort, and a broadly more stable money velocity in the upper cohorts.

We can see how this impacted consumer price inflation when we overlay the CPI curve.

Broadly speaking, as each wealth cohort has seen an increase in money velocity, it presents an inflationary pressure on the economy, and as each wealth cohort has seen a decrease in money velocity, it has presented a disinflationary or deflationary pressure on the economy. Thus the monetary easing post-2008 did not produce significant inflation, as the rising monetary velocity of the lowest wealth cohort was largely negated by the declining monetary velocity of the upper wealth cohorts.

Post-COVID, we see that the money velocity of the lowest and highest wealth cohort increased, while that of the middle cohorts decreased at first, and then increased. Based on what we’ve seen thus far, the impact on inflation is eminently predictable.

We can even see the impact of the COVID stimulus payments4, given the timing of each piece of legislation.

The first stimulus payment correlates to an increase in money velocity across all cohorts, with the middle cohorts tapering off almost immediately. The second stimulus payment correlates to an increase in money velocity in the lowest economic cohort greater than that of the top cohort, with the third payment increasing that money velocity of the lowest cohort even more. Thus by catalyzing greater money velocity, the stimulus payments touched off consumer price inflation.

Referring back to the rate of wealth increase post-GFC, we can see the signature difference between government policy after the GFC vs the COVID pandemic was the direct-to-consumer injection of cash in the form of stimulus payments. While the QE after the GFC remained within the financial markets, sparking asset price inflation and not consumer price inflation, post-COVID significant injections of cash were made outside of the financial markets, and thus inflation resulted.

Moreover, as money velocity within the lowest wealth cohort peaked, so did consumer price inflation. However, the declines in money velocity in the lowest wealth cohort are being offset by increases in money velocity among the other wealth cohort. This also helps to explain why the Fed’s rate hike strategy has had little to no effect on core inflation.

The disinflationary trend we would expect to see as the monetary velocity of the lowest wealth cohort declines is being largely offset by the rising monetary velocity of the other cohorts. The Fed arguably has succeeded in pushing down consumer spending of the lower economic strata, but consumer spending of the upper cohorts has not be blunted by the Fed’s rate hike strategy.

Keep in mind that blunting the spending of working-class folk—i.e., the lowest wealth cohort—has been the Fed’s strategy all along. As readers may recall from last year, this was publicly stated, and not just by Jay Powell.

However, further on down, Barkin said the quiet part out loud about what “whatever it takes” really means (emphasis mine).

Barring an unanticipated event, I see rising rates stabilizing any drift in inflation expectations and in so doing, increasing real interest rates and quieting demand. Companies will slow down their hiring. Revenge spending will settle. Savings will be held a little tighter. At the same time, supply chains will ease; you have to believe chips will get back into cars at some point. That means inflation should come down over time — but it will take time.

Let that bit sink in. The reason rate hikes “work” to cure inflation is that rising interest rates make the cost of credit (aka, the “cost” of money) too high for consumers to utilize. Consumers are forced to spend less. Along the way, a few jobs are wiped out, a few workers are laid off, and eventually prices come down.

The Fed got what it wanted—and it didn’t do a damn thing about inflation.

This outcome should not really surprise anyone, least of all professional economists such as those employed by the Federal Reserve. Even though Milton Friedman acknowledged the role of money velocity in inflation, he was quite explicit that the impact of money velocity was highly variable. There is no magic formula that allows for money velocity to be finely tuned so as to negate consumer price inflation.

What the Fed’s strategy does serve to illustrate, however, is that focusing on a few headline metrics, which the Fed has explicitly done, is nothing if not counterproductive. The Fed’s signature mistake has been to presume that all consumers are created equal, and that Fed policy falls on all consumers equally. As the data presented here shows, that is simply not the case. Because policy hits different consumers differently, it is quite easy—and even predictable—that the impacts on one cohort of consumers will be either negated or amplified by the impacts on other cohorts.

The Fed’s own strategy has been the way the Fed has shot itself in the foot.

In the long term, the impacts of money velocity on inflation will trend towards an equilibrium, at which inflation’s rise and fall will largely follow the growth or contraction of the money supply. This is why we are constantly inundated with the oversimplification that inflation is the result of too much money being created—broadly speaking, that is correct, but the process by which inflation expresses itself year to year and even month to month is rather more nuanced, and is impacted in the short term more by money velocity than the growth in the quantity of money itself.

We should be thankful this is the case, for if the relationship were directly and solely to money supply growth, the Fed’s ginormous expansion of the money supply post-pandemic would mean we would be seeing hyperinflation on a par with the Weimar Republic or Zimbabwe, as prices rose to match the overall money supply.

Fortunately, this has not happened—yet. Eventually it must, for if the Fed cannot bring down the size of the money supply, prices will sooner or later rise of a corresponding magnitude. This was the relationship we saw pre-GFC where the M1 money supply growth largely tracked consumer price inflation.

Yet this same reality also shows us the shortcomings of the Fed’s strategy—not only has it not succeeded, it was never possible for it to succeed. While the Fed has noticeably reduced the money supply, inflation has not followed suit.

The Fed has reduced the M1 money supply by 11% from its April 2022 peak, and the M2 money supply by 5.2% from its April 2022 peak, yet core inflation has not come down anywhere near that much.

As money supply growth produces inflation, money supply reductions should produce deflation—prices should be coming down, not merely rising more slowly (disinflation). We have not seen that.

Money velocity—and the disparities in money velocity among various wealth cohorts, tell us why this is so. Just as the rapid money growth post-COVID did not produce extreme hyperinflation because of the drop in money velocity, rising money velocities are preventing deflation from presenting now that the money supply is contracting.

The Fed’s signature mistake was thinking that interest rate hikes would impact all consumers equally. As we have seen just in the inflation data, the money velocity data, and the wealth data, that has never been the case. To reiterate the point I have made repeatedly in this Substack, inflation is not merely a rise in prices but a distortion in prices. It is a distortion not just of prices for the goods and services consumers buy, but of the dollars consumers have with which to buy.

By not acknowledging the fundamental iniquities presented by inflation, the Fed has failed in its goal of constraining inflation.

Friedman, M. “Inflation: Causes and Consequences. First Lecture.” Dollars and Deficits, Prentice Hall, 1968, pp. 21–46. Retrieved online from https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/271018/full

"follow the money." Farlex Dictionary of Idioms. 2015. Farlex, Inc 29 Jun. 2023 https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/follow+the+money

Friedman, M. “Inflation: Causes and Consequences. First Lecture.” Dollars and Deficits, Prentice Hall, 1968, pp. 21–46. Retrieved online from https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/271018/full

US Department of the Treasury. Economic Impact Payments. 2 May 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-american-families-and-workers/economic-impact-payments.

Thanks for reminding me of this. I’m not sure I read it before. If only more people were talking about this. I have only recently realized that the class divide is caused by not having investment income . Half the country cannot keep up with the cost of living because it rises based on demand (money velocity?) that is driven by the investor class and up. In other words, there’s no longer an affordable product in many consumer categories, like cars, houses, appliances, insurance for the working class unless you have at least two incomes and that’s no guarantee . As far as reducing demand, you can’t reduce demand from people who can only afford basic necessities. If they really want to reduce demand they’ll need a consumption tax on the rich.