Everyone not living on a deserted island has heard the aphorism “the truth hurts”.

If we take the Bureau of Labor Statistics at face value—and yes, that is an heroic assumption at best—then the August Employment Situation Summary is clear proof this is so. For once the BLS favorite rhetoric that the labor metrics are “little changed” might actually be appropriate. With almost no job growth reported for the month, the labor outlook in the US is indeed “little changed”, and that means it is still not at all good.

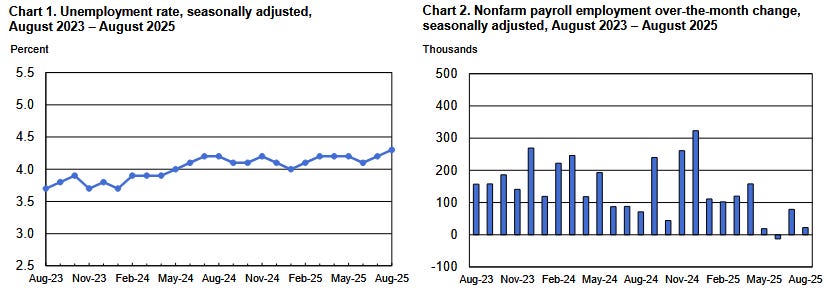

Total nonfarm payroll employment changed little in August (+22,000) and has shown little change since April, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported today. The unemployment rate, at 4.3 percent, also changed little in August. A job gain in health care was partially offset by losses in federal government and in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction.

Against the size of the US labor force even in a jobs recession, growth of 22,000 jobs is not only little change, but almost imperceptible change.

As the charts accompanying the news release highlight, August was a continuation of the twin trends of rising unemployment and diminishing job growth.

Even Lou Costello Labor Math could not salvage the August jobs report. That tells you how grim the data is.

Peeling back the layers of detail only shows that the data is even worse than the report indicates.

Contents

Data Quality Still Suspect

Before we delve into the data, we first must acknowledge that the data is still of dubious quality at best. The jobs numbers are not good, yet there are still the telltale signs of Lou Costello Labor Math at work.

An obvious quick “tell” is the continued divergence between the Household Survey and the Establishment Survey data sets.

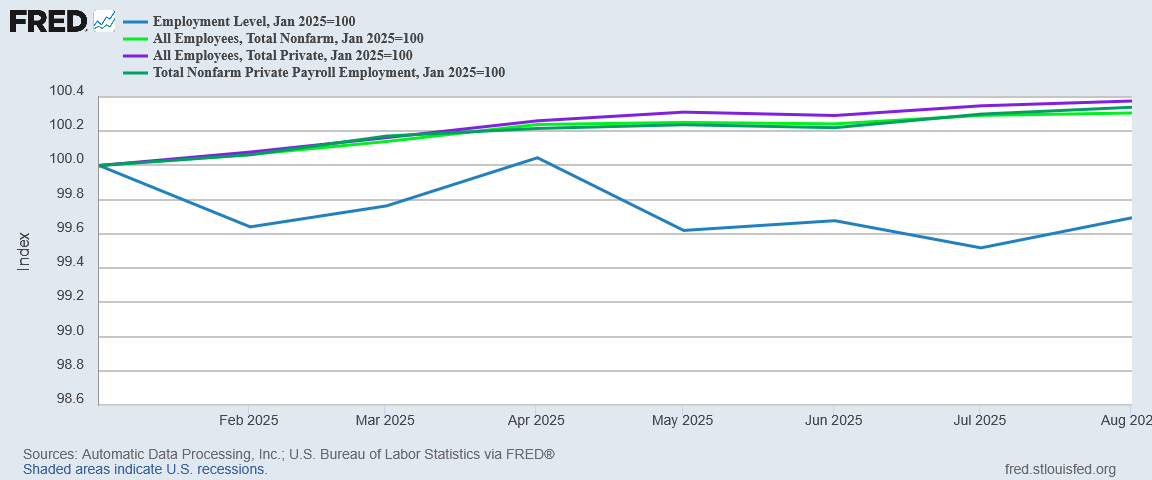

When the Employment Level charts declining employment and payroll levels both from the BLS Establishment Survey and the ADP National Employment Report, something is egregiously wrong with the data itself.

We get further confirmation of this from the continued downward revisions to prior months jobs numbers.

The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for June was revised down by 27,000, from +14,000 to -13,000, and the change for July was revised up by 6,000, from +73,000 to +79,000. With these revisions, employment in June and July combined is 21,000 lower than previously reported.

Year to date, the BLS’ corrections to prior months mean that some 482,000 jobs initially reported in the Employment Situation Summary never really existed.

Such persistent overstatement of the jobs numbers is strong evidence that the data quality is still extremely poor.

While President Trump’s charges of political bias at the BLS might lack solid evidence, the BLS jobs data is still of demonstrably poor quality and still speaks to incompetence and ineptitude in gathering jobs data.

Straight away we have to acknowledge that the jobs data remains tainted and suspect. This imposes severe limitations in what we may assess from the jobs data.

Jobs Weakness Across The Board

Tainted or not, one consistency the data does show throughout is weakness.

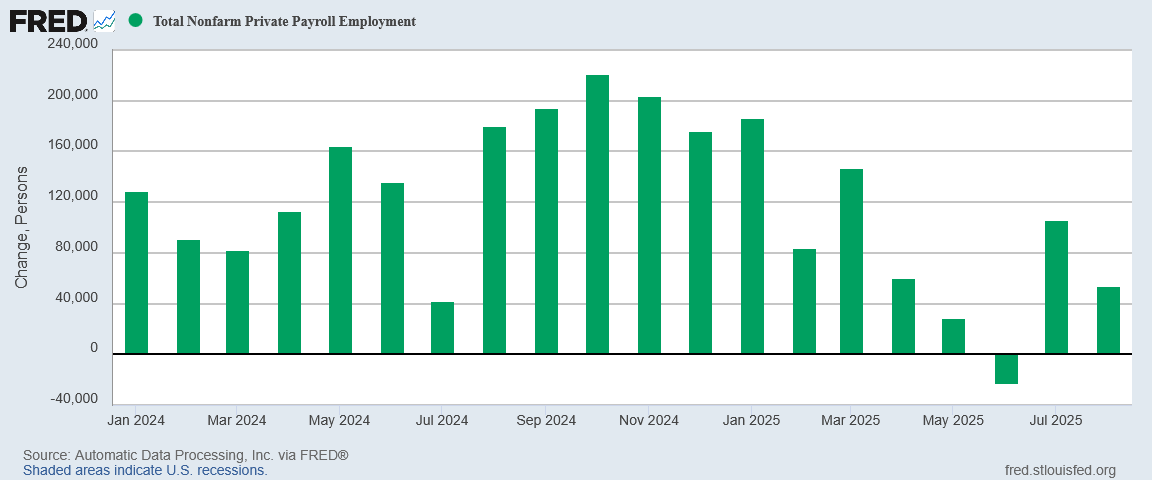

Total non-farm job growth per the BLS Establishment Survey is weaker thus far this year than in 2024.

Even with government jobs excluded, the Establishment Survey still paints a deteriorating picture of private sector job growth.

Even the ADP jobs data shows job growth weaker this year than last.

The Household Survey’s Employment Level data has been poor since before 2024.

Tainted or not, the data does not provide any basis for assessing an improving jobs situation in this country.

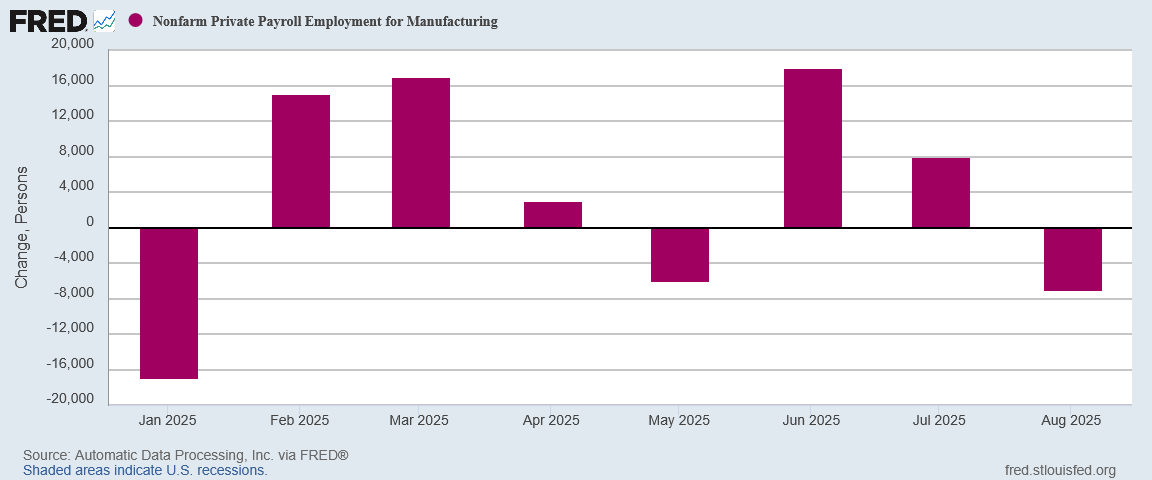

Drilling further down, the BLS data shows manufacturing has been hemorrhaging jobs throughout the year.

The ADP report shows manufacturing doing better, although there was still manufacturing job loss in August.

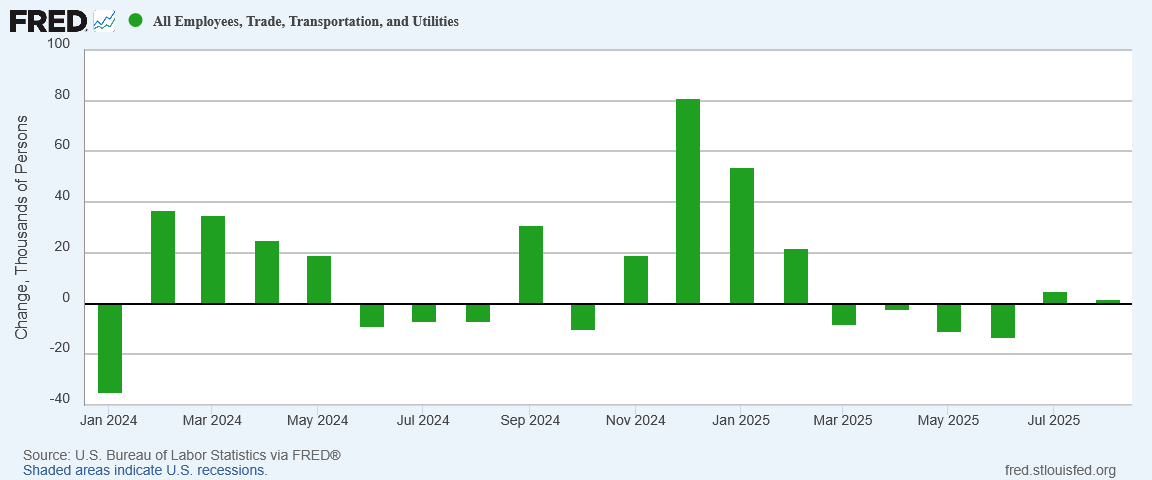

On the service side, Trade, Transportation, and Utilities has underperformed since the start of the year.

Private Education and Healthcare, which has carried job growth a few times in the past, is showing a clear deterioration relative to 2024.

Even with suspect data, it is difficult to dismiss the negative trend in job growth when it is consistent even at the sector level.

The jobs recession is continuing, and continuing to get worse.

Manufacturing Not Recovering Yet

Lending credibility to the negative jobs numbers particularly in the manufacturing sector is the reality of non-BLS data sets showing manufacturing has not yet turned around from the decline of the Biden era.

A spike in capacity utilization during the first quarter of the year has not been sustained since, leaving manufacturing well short of its Biden-era capacity utilization peak in March, 2022.

There are exceptions to this decline, however. The tech sector in particular has been growing steadily since Donald Trump assumed office.

However, while technology is an important manufacturing subsector, relative to total manufacturing capacity in the US its contributions are marginal, leaving capacity utilization with and without the tech sector included nearly identical.

Looking at a cross section of the stages of production does not make the capacity utilization data any better.

The one thing manufacturing capacity is demonstrably not doing in this country is expanding.

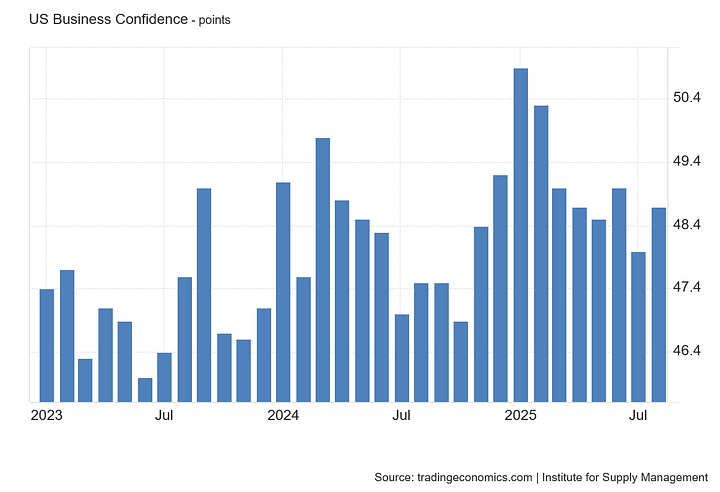

Recent PMI data gives little reason for near-term optimism. The Institute for Supply Management shows manufacturing to have been in contraction almost non-stop since 2023. S&P Global’s Manufacturing PMI is showing greater strength, and even signs of a trend reversal into expansion, but even that growth is fairly recent in origin.

Multiple data sets from multiple sources show manufacturing in the US to be sickly and anemic, and that gives the BLS manufacturing job loss data a lot of credibility it would not otherwise have.

Ironically, one area where things are growing in the Trump 2.0 Era is retail sales, which has posted consistent nominal dollar growth year to date.

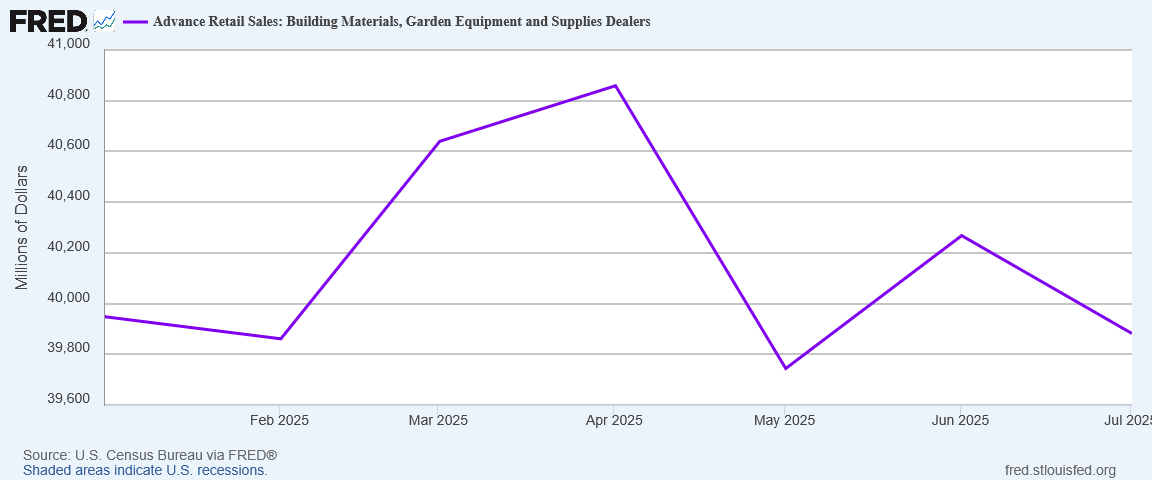

However, there is a caveat even within that data—retail sales for building materials has seen a sharp decline since April.

While the data does show that consumption is rising, and carrying retail sales with it, the stagnant housing market is stifling related retail markets for necessary inputs such as building materials.

Growing retail sales and consumption does power overall economic growth, but until consumption growth starts to induce production growth, the actual economic benefits derived from the growing retail sales are at best limited. Retail sales are up, but they are not producing the necessary economic cross-pollination into manufacturing the economy needs to drive sustainable growth.

Real Weekly Earnings Still Not Recovered

Adding to workers’ misery is the reality that weekly paychecks have yet to fully recover from the 2022 hyperinflation cycle.

While real goods producing weekly earnings have been rising in recent months, they remain below where they stood in January of 2021.

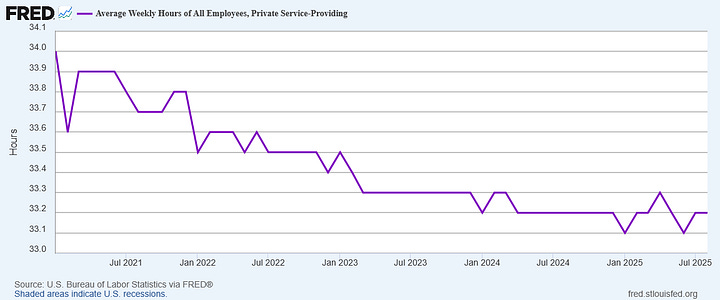

Weekly earnings for service workers are lagging even further behind January 2021 levels.

It is difficult to credibly speak of wage growth when real wage recovery from inflation has yet to take place.

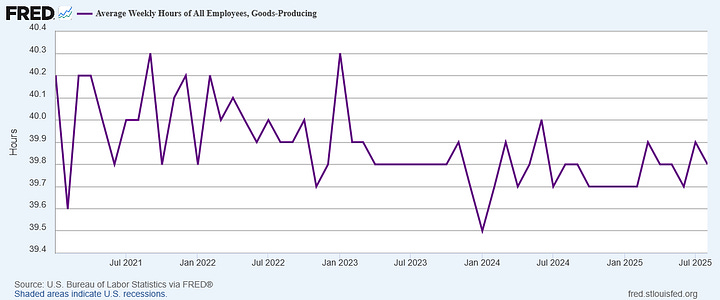

The devil in the data which continues to undermine weekly earnings: average weekly hours worked, which are still trending down for both goods producing and service jobs.

When workers are putting in fewer and fewer hours, growing their weekly earnings will remain an uphill battle.

The continued decline in hours worked is itself another indicator of economic weakness. While companies might be reluctant to hire workers for various reasons of economic uncertainty, if there were rising demand for goods and services, one metric which would serve as an early indicator of this would be rising weekly work hours.

Paying workers a little overtime is frequently a lower-cost alternative to increasing headcount. If there was an increasing need for output, this would make paying overtime a more attractive initial response to growing demand. Rising economic output should produce rising weekly hours worked. So far, that has not happened.

This Is Not A Golden Age

Despite Donald Trump’s hyperbolic posts on Truth Social, America is demonstrably not in a “Golden Age.”

That was true when the July JOLTS data came out and it remains true with the August Employment Situation Summary.

The economic data does not support claims of a “Golden Age” in the slightest. There is a perverse irony that Wall Street economic “experts” such as Moody’s Analytics Mark Zandi suddenly discovering that America has entered a “jobs recession”.

Zandi is right but about two years too late. America has been in a jobs recession since at least 2023.

In the studied habits of hypocrisy that is emblematic of the Wall Street “expert”, Zandi was willing to overlook jobs weakness under Joe Biden but is triggered by it under Donald Trump.

Predictably, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent pushed back on the notion yesterday on NBC’s Meet The Press, when Kristin Welker challenged him with Zandi’s diagnosis.

"We’re not going to do economic policy off of one number," Bessent said. "Good policies are in place that are going to create good high-paying jobs for the American people."

What Bessent conveniently leaves out of his rebuttal is that the jobs recession conclusion is not based on “one number”. Mark Zandi might just recently have noticed America’s jobs weaknesses, but the same data sets he uses to conclude that the jobs recession has just started are the same data sets which show the jobs recession started in the fall of 2023.

Bessent is right to point out the ongoing data quality issues at the BLS. The jobs data is tainted. However, tainted or not, that data intersects with other independent data which chart substantially the same trends and the same labor market weaknesses. The numbers may be off, even wildly off, but the broader macro trends are far less so.

Moreover, while there is likely to be another major benchmark revision as there was last fall, erasing potentially hundreds of thousands of jobs from the 2024 numbers is not going to turn 2025’s anemic month on month jobs gains into robust job growth. All the benchmark revision will do is lower the 2025 starting point. For 2025’s numbers to point to robust job growth the current 2025 payroll levels would have to be accurate while the 2024 levels extremely inaccurate.

No great economic or statistical expertise is needed to understand the sheer lunacy of such a position—and yet that is what Bessent fundamentally argued on Meet The Press.

This is not to say that Donald Trump is not attempting to address the country’s economic woes. Quite the contrary, as his recent efforts to secure a new and hopefully improved trade deal with Japan indicate, he takes economic growth quite seriously.

Investment deals such as Hitachi Energy’s recent commitment to a $1 billion investment to expand the US electric power grid are indisputably pregnant with job growth potential.

Indeed, President Trump is to be highly commended for making investment—both foreign and domestic—a primary focus of his second term of office, something his frequent social media posts demonstrate. One thing to which Donald Trump is undeniably committed is seeing business investment in the United States grow. Whether his approach to growing business investment in the United States proves successful remains to be seen, but in policy terms it cannot be argued that he does not have his economic priorities in order.

Still, while the announcements coming out of the White House do indicate that Trump is having success in persuading companies to invest in operations inside the United States, there is no indication yet that these investments have begun to yield fruit in the form of increased employment and structural increases to wages and earning. It is true that factories do take time to build and staff, but until those factories are built and staffed, Trumpian backslapping about American being in a “golden age” are at best premature.

Are we in a period of necessary correction before true prosperity can return? Perhaps.

Whether we are in a period of economic correction or a period of economic policies that need correction, however, the immediate outlook for the American worker remains not one of employment and wage growth, but deepening jobs recession and wages slow to recover from previous hyperinflation.

Wages are recovering but they are not there yet. Hours worked have yet to even turn around.

That is not a “Golden Age” for American workers. That is a continuing jobs recession for American workers.

As did Joe Biden before him, President Trump does love his economic victory laps. Unfortunately, also as Joe Biden before him, those victory laps are frequently not at all earned, and are often at odds with the realities of the US economy.

The “Golden Age of America” is not yet here. Whether it will eventually get here is something we do not yet know, Trumpian social media cheerleading notwithstanding.

I think your final statement is the most poignant: The “Golden Age of America” is not yet here. Whether it will eventually get here is something we do not yet know, Trumpian social media cheerleading notwithstanding.

“…not YET here,”…”something we do not yet know.” The Trump admin has a LOT to undo. I am cautiously optimistic and hope that the next year sees his strategies bear fruit. Short-term pain for long-term gain. Because right now, NONE of us knows what the future will bring.

You consistently state the bald truths, Peter. I would love to see a debate between you and Mark Zandi, or any of the other self-important pundits spewing skewed data. Zandi is two years behind you in seeing the true picture? He should go into another line of work.