Fake Job Openings Are Disappearing

JOLTS Report Continues The Equally Fake Narrative On Jobs

If you believe the Bureau of Labor Statistics June Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary Report, you might conclude that the job market is easing after having been very tight for quite some time.

The number of job openings was little changed at 9.6 million on the last business day of June, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the month, the number of hires and total separations decreased to 5.9 million and 5.6 million, respectively. Within separations, quits (3.8 million) decreased, while layoffs and discharges (1.5 million) changed little. This release includes estimates of the number and rate of job openings, hires, and separations for the total nonfarm sector, by industry, and by establishment size class.

With fewer (fake) job openings, you might even conclude that the Fed’s rate hikes were finally killing off jobs in this country, in accordance with the Fed’s stated strategic objectives on inflation.

Certainly the corporate media believes and has concluded as much.

The number of job openings in the United States decreased to 9.6 million in June, showing signs of contraction as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates.

The new numbers, which look at openings across all sectors for that month, were released as part of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, which was updated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Tuesday. While still relatively strong, the decrease is notable and marks the lowest level of job openings since April 2021.

The decline was also notable because it was more pronounced than most economists had expected.

The falling number of openings is a sign that the labor market, which has held up despite a series of major threats over the past two years, might be starting to take a hit from the Fed’s rate hikes.

That’s the narrative. What about the data?

At this point, it is no longer a surprise that the total number of non-farm job openings in the US still greatly exceeds any semblance of the historical norm—a phenomenon made more improbable by the lack of any similar increase in hiring.

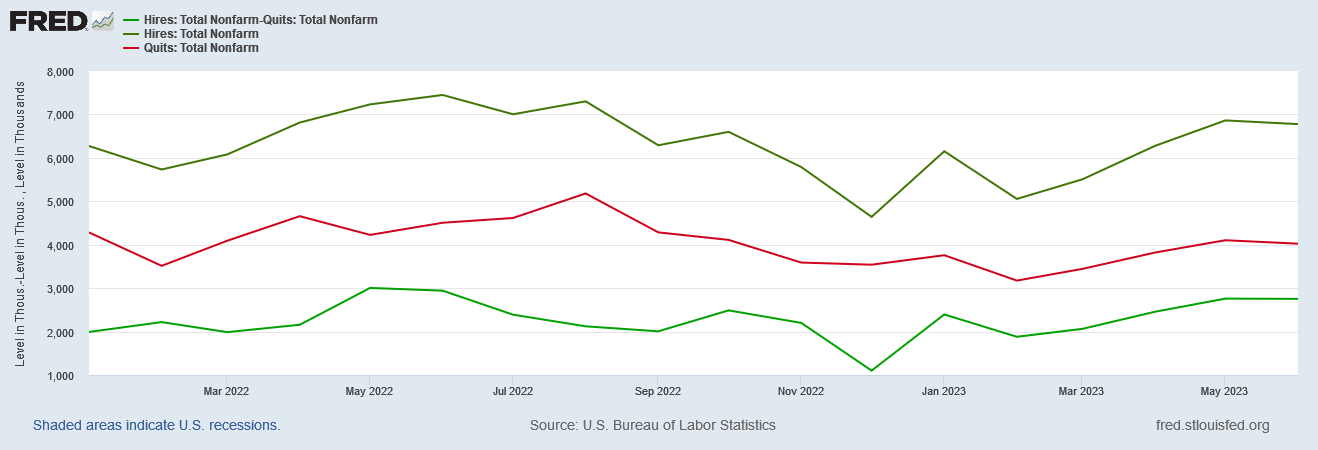

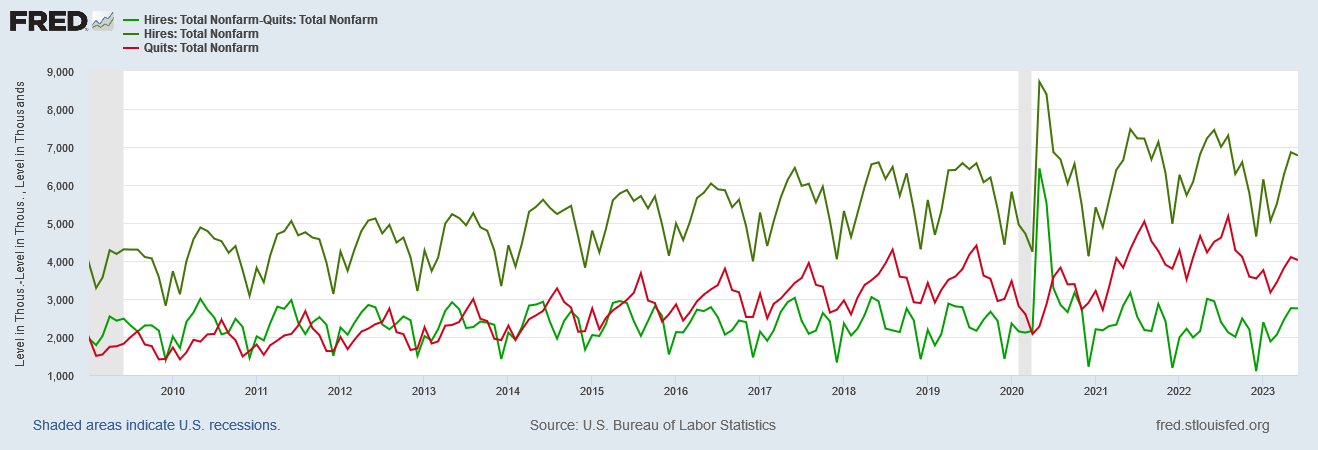

Outside of the Pandemic Panic Recession, and prior to 2021, job openings as well has total hires and total separations primarily fluctuated within the range 4,000,000 to 7,500,000 jobs. It was only after 2020, and after the 2020 Pandemic Panic Recession, that job openings surged upward—but job hires did not. Neither did separations fall below that range.

It still beggars belief that there were, as of June, 2023, some 8,450,000 more unfilled job openings than there were net positions filled (total hires less total separations, or 6,777,000 hires less 5,938,000 separations). It further beggars belief that the numbers do not show any great sense of urgency at filling the open positions. Millions of open jobs every month and yet employers are seemingly feeling no pressure to accelerate their hiring efforts.

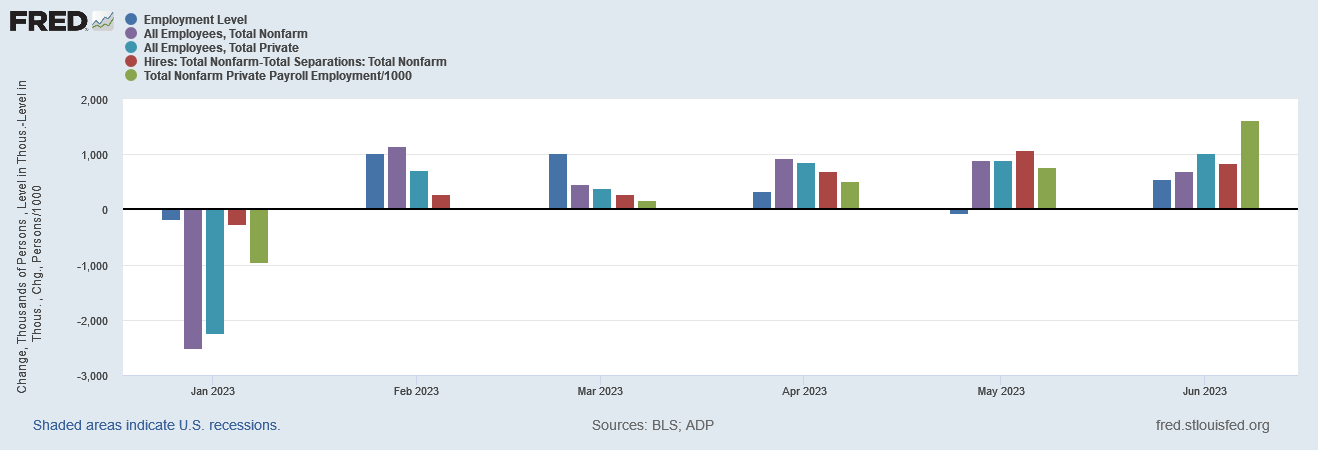

The lack of credibility behind the JOLTS numbers is also attributable to the significant variance between the various levels of job creation and hiring found in the Employment Situation Summary, the ADP National Employment Report, as well as the JOLTS report.

Notionally, there should be at least some convergence between the various calculations of new employees added to payrolls in June. There isn’t. If the various job reports do not agree with each other than all of them should be taken with a grain of salt until there is sufficient trustworthy data to allow a proper reconciliation of their numbers.

The JOLTS report itself continues to give us plenty of reason to doubt the preferred corporate media narrative on the nature of labor markets.

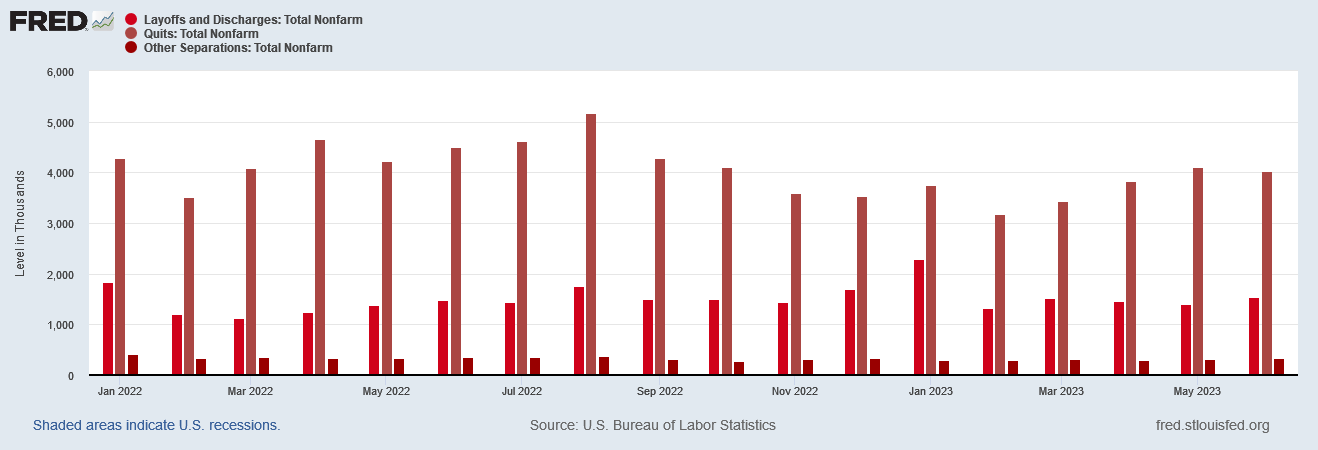

The most significant is that the level of quits relative to other forms of job separation continues to be quite elevated. The “Great Resignation” is still very much a thing, suggesting that people are changing jobs with greater than normal frequency.

Nor is the excess merely incremental. Since January 2022, the number of quits each month has been roughly twice the number of all other separations combined.

By a very wide margin, most job separations in this country are being reported as quits. People are leaving a job voluntarily rather than being laid off or fired.

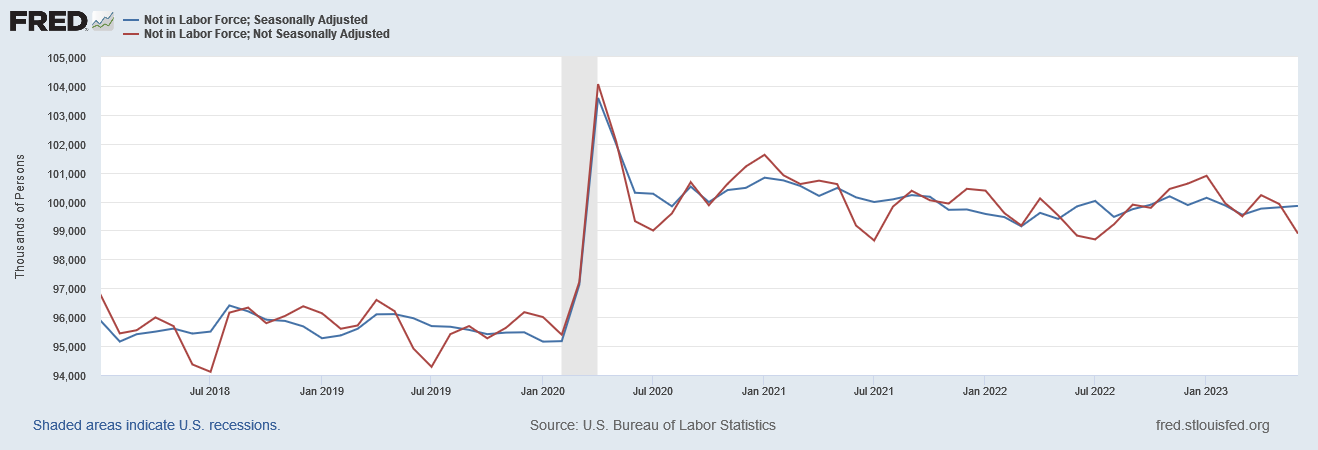

This suggests that much of the hiring being reported is little more than churn—workers are essentially moving from one job to another, thus producing less actual job growth. This view also explains why nearly half of workers sidelined and effectively expelled from the labor force during the Pandemic Panic Recession remain out of the labor force today.

With most workers merely rotating around and consuming most of the actual job openings, the amount of actual hiring left to pull workers not in the labor force back into the labor force is simply not that great.

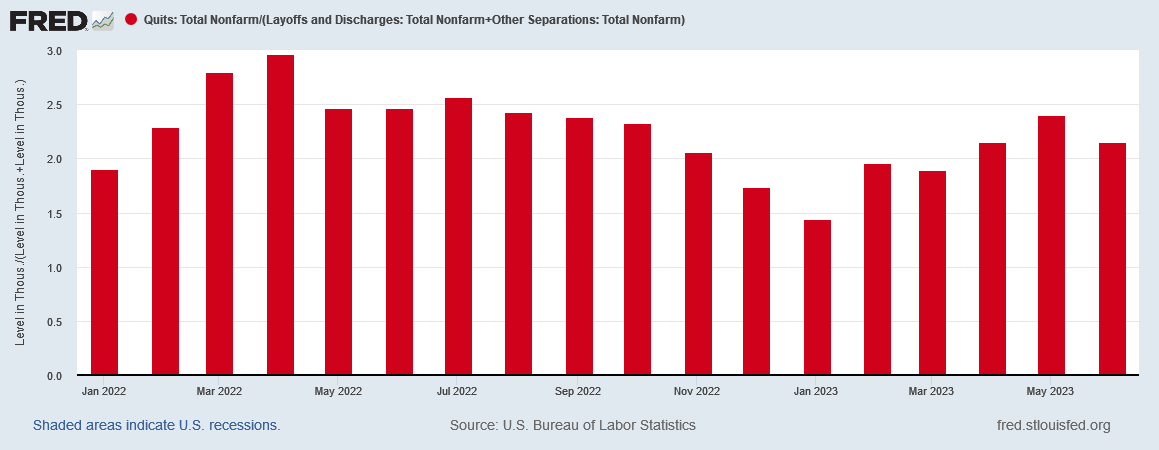

Such a view of the pace of hiring also means that there is considerably less demand for new workers than the headline hiring number might suggest. We can get a glimpse of this reduced demand for workers if we look at the hiring data with the number of quits removed.

If we assume that each person who quits their job has moved to another job, then each quit is potentially matched by a hire, and thus the real shift in labor demand would be the total hires with the number of quits (i.e., the churn) removed.

If we look at the data stretching back to the end of the 2007-2009 recession, we can see that the actual growth in labor demand has been fairly consistent over that time, but that there has been an increasing amount of labor churn.

This, of course, is merely a reaffirmation of how increasingly toxic US labor markets have become over time, as opposed to the prevailing narrative of them being “tight”.

However, while the reported number of job openings may be of questionable validity, and the overall patterns of job hires and separations points to a labor market of far different quality than what promoted by the official narrative, it does appear that the one aspect of the JOLTS report that appears to have the greatest connection to reality is the rising number of separations.

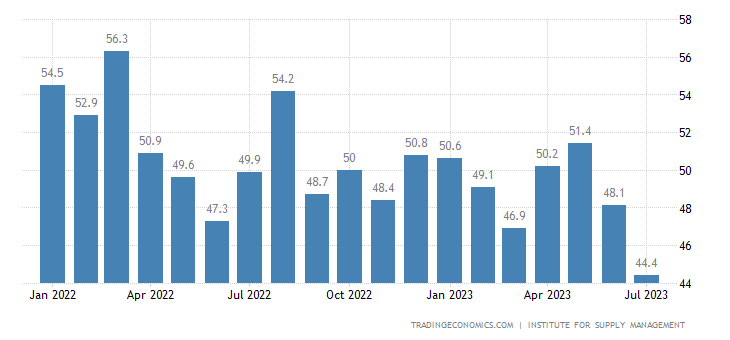

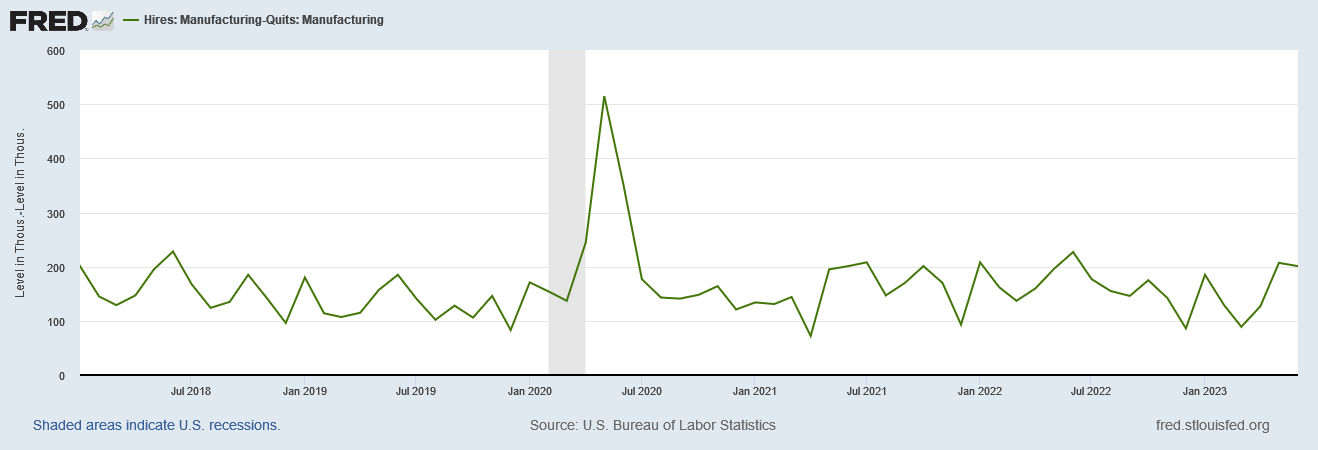

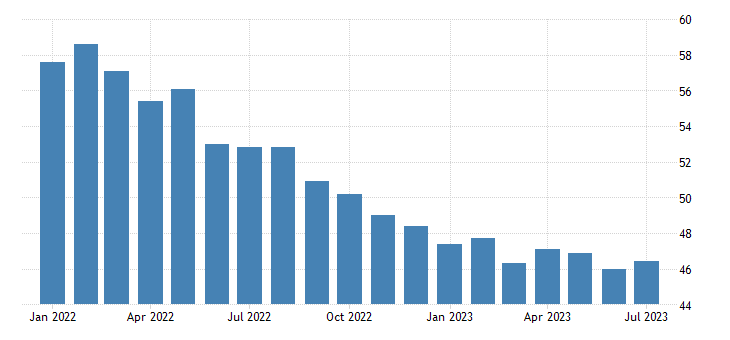

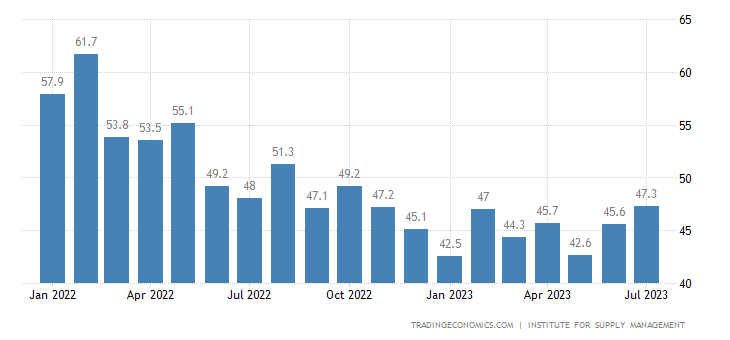

Given that, according to the Institute for Supply Management June and July employment subindex to the Manufacturing Purchasing Manager’s Index, employment has been dropping, we have to contemplate that the rising separations number has some external validation.

This becomes even more credible when we look at manufacturing hires per the JOLTS report with the quits factored out.

At best there has been no appreciable growth in manufacturing labor demand.

With the whole of the manufacturing side of the economy deep in a contraction that has lasted for the past nine months (and counting), declining employment in manufacturing is not at all unreasonable.

The decline in new manufacturing orders gives us every reason to be pessimistic about the employment growth prospects going forward.

By all outward appearance, US manufacturing and US manufacturing employment are very much in recession, despite what the corporate media narratives say.

All of which underscores just how much the JOLTS report has once again delivered a picture of the US labor market that is significantly at odds with reality.

Job growth in manufacturing is demonstrably not really happening—which means job loss either is just around corner or has already begun.

Labor markets are still not bringing in a substantial fraction of the some 8 million workers forced out of the labor force during the Pandemic Panic Recession.

Despite the artificially inflated job opening levels reported each month in JOLTS, actual labor demand has not significantly increased since before the Pandemic Panic Recession.

A steadily rising number of job quits indicates workers are increasingly dissatisfied with their jobs. US labor markets have not been “tight” as the narrative suggests, but rather toxic instead.

Neither the JOLTS report itself nor the corporate media narratives regarding the report address any of these less than optimistic patterns discernible in the data. Neither the JOLTS report nor the corporate media narratives regarding the report acknowledge the realities of recession which are spreading throughout the US economy.

Looking at the data, we can divine much about the state of the labor side of the US economy. Just don’t expect to see any of what is there to be seen reflected in the official narratives.

How does the Actuaries data relating to increased disabilities and injured factor in to the jobs advertised vs actual hires?

Like change in roles or long term sickness leave would potentially "create" job openings, yet if the person is not actually "left" the position, then how does it get categorised? Sorry I don't think I explained my question well!

Basically, how do the job data consider disabilities data?🤗

At least one of those job openings wasn't fake. After graduating from college in May of 2020, when nobody was hiring, then getting a masters in December of 2021, when everyone who was hiring insisted that employees take risky injections first (something she wasn't willing to do), she finally found a job commensurate with her education last month. Yay! :)

But yeah, she'd been looking for a year and a half, and also concluded that many of the "openings" were indeed fake.