Feckless Fed Is Destroying Demand, But Not Inflation

They Ignore The Data At Their Peril...And Ours

All Wall Street eyes are looking to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, this week, and Fed Chairman Jay Powell’s upcoming speech at the Federal Reserve’s annual Jackson Hole Economic Symposium on Friday. In particular, professional Fed watchers are looking for clues from Powell on what the Fed will do next in its heretofore largely ineffective fight against inflation, and what that will mean for the economy as a whole

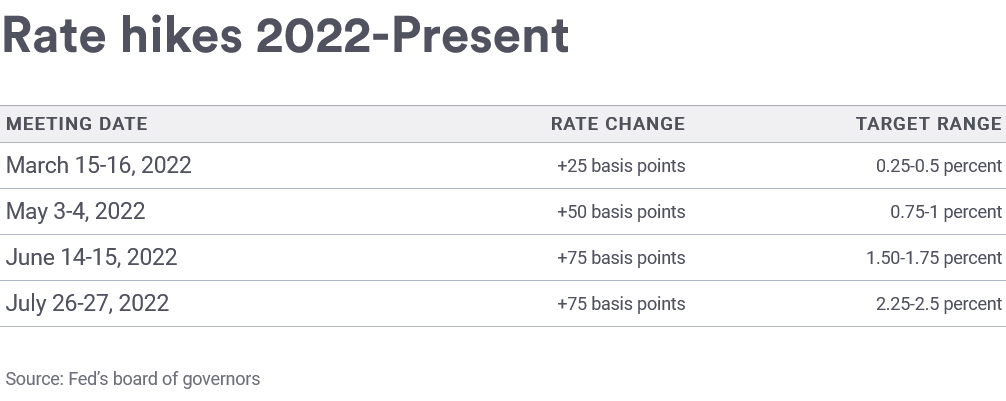

Powell may use the opportunity to double down on the central bank’s recent hawkish posture, which has seen the Fed raise interest rates by 75 basis points in its last two monthly meetings. Or he could use the occasion to clarify the Fed’s position as Wall Street suffers recent jitters after a summer rally that was born of better-than-expected inflation readings in July.

There is, however, one small problem with hanging on Jay Powell’s next words: the Fed Chair has not shown any indication he understands the data unfolding daily. Instead of fretting over what Powell might hint about the Fed’s next inflation fighting moves, Wall Street—and Main Street—would do well to consider what the data is saying about the Fed’s inflation fighting moves thus far.

Hint: the data is not saying anything good.

Rate Hikes Have Had Minimal Impact On Treasury Yields (And On Inflation)

The 10 Year Treasury Yield, on the other hand, rose from 1.512% on December 31 of last year to 3.483% on June 13—an increase of 130%—before dropping down to the most recent close at 3.052%.

The cumulative effect of a 900% increase in the Federal Funds Rate has been a mere doubling of 10 Year Treasury Yield. That’s not exactly a demonstration of central bank strength and influence.

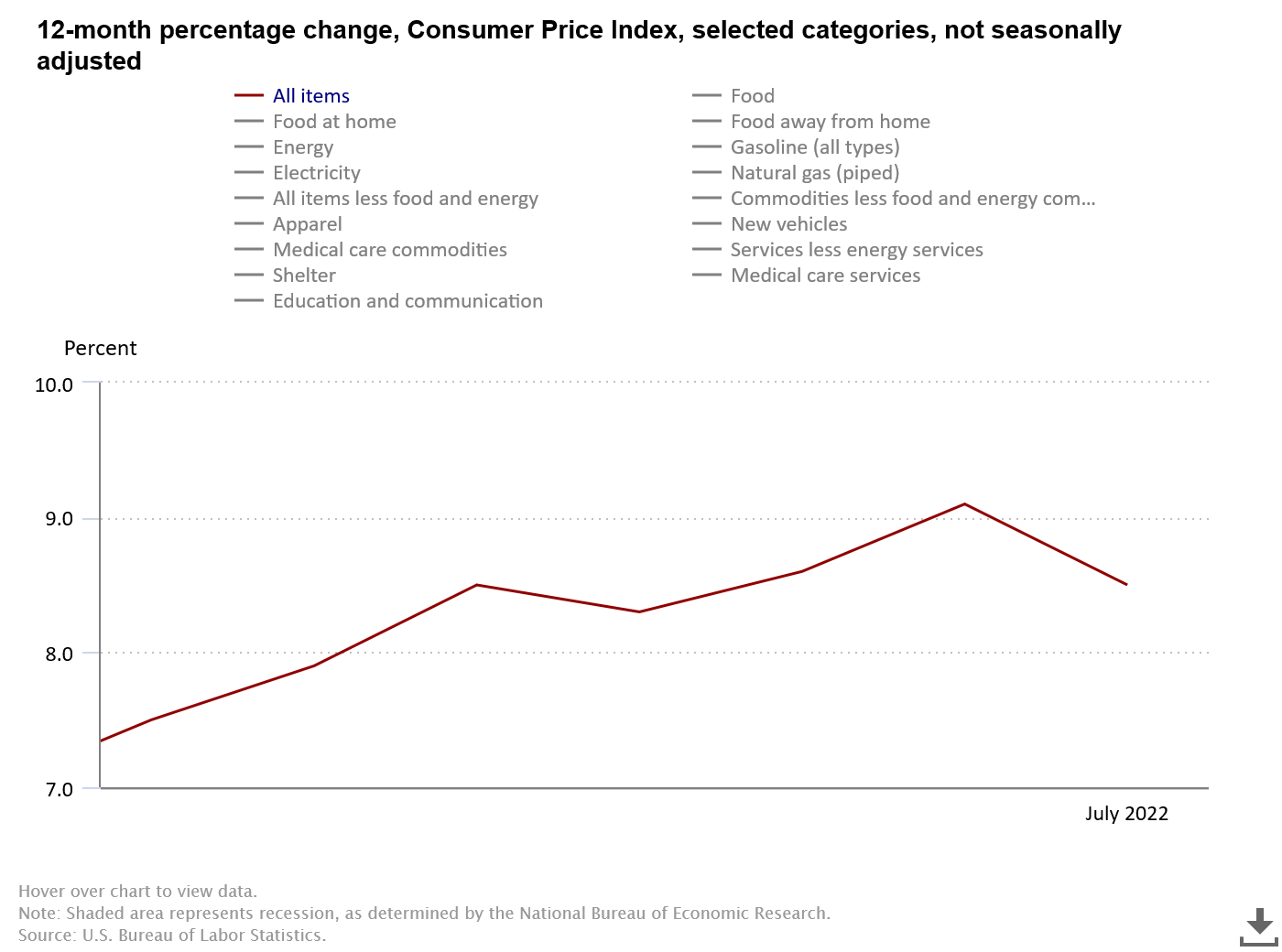

The effect of the 900% increase in the Federal Funds Rate on inflation: zero—July’s year-on-year inflation rate was the same as March’s year-on-year inflation rate: 8.5%

The best case that can be made for the efficacy of the Fed’s rate hikes is they have hindered rising inflation. They certainly have not stopped it—not yet, at least.

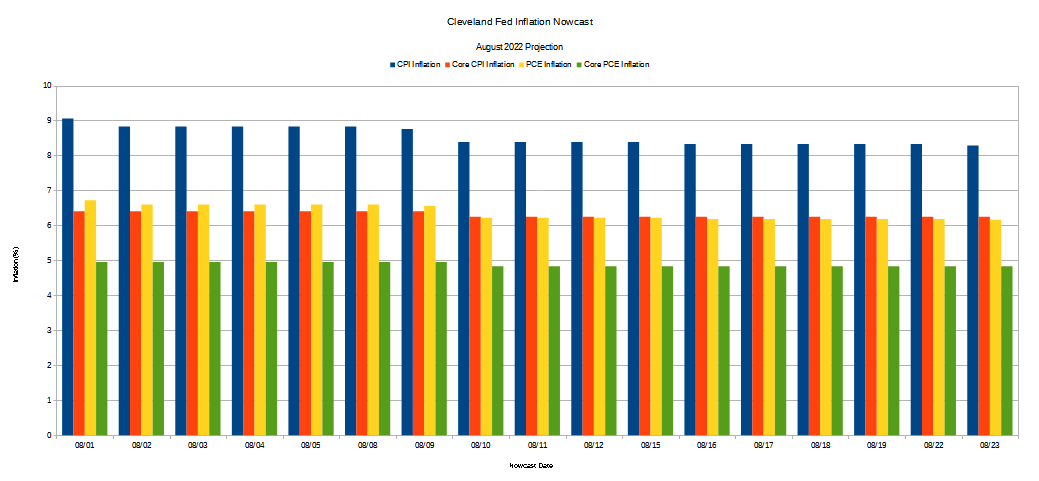

Nor are the rate hikes forecast to have much influence on inflation going forward. The Cleveland Fed’s inflation nowcast puts headline consumer price inflation at 8.28%, slightly more than 0.2% down from July. Core CPI and PCE inflation rates are similarly nonplussed by the Fed’s hikes.

Meanwhile, The Economy Is Spiraling Downward

What is neither minimal nor marginal has been the overall contraction within the US economy of late, as multiple independent economic indicators illustrate.

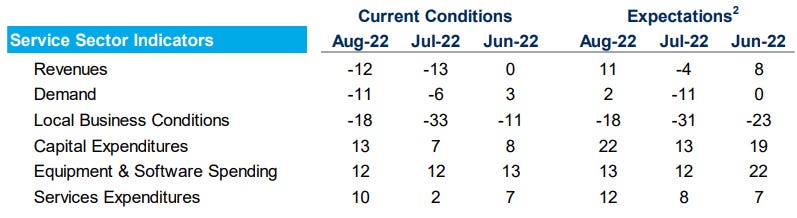

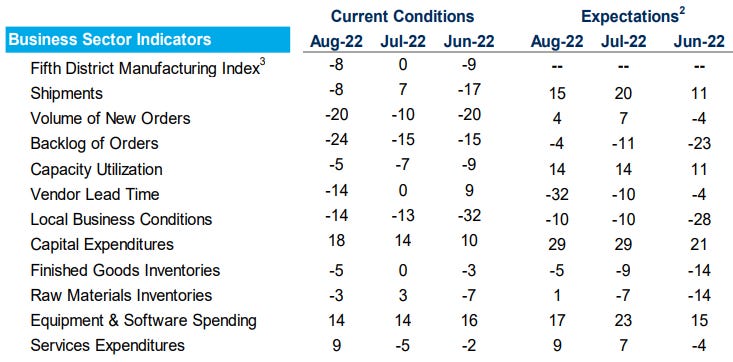

In today’s release of the Richmond Fed’s Fifth District Survey of Service Sector Activity, the Fed reported declining activity throughout the Richmond Federal Reserve District, with revenues “improving” by deteriorating less (index from -13 in July to -12 in August). Demand fell through the floor, and local business conditions remained deeply negative.

The Manufacturing Survey was worse, with 7 of 10 indicators posting significant declines for the month.

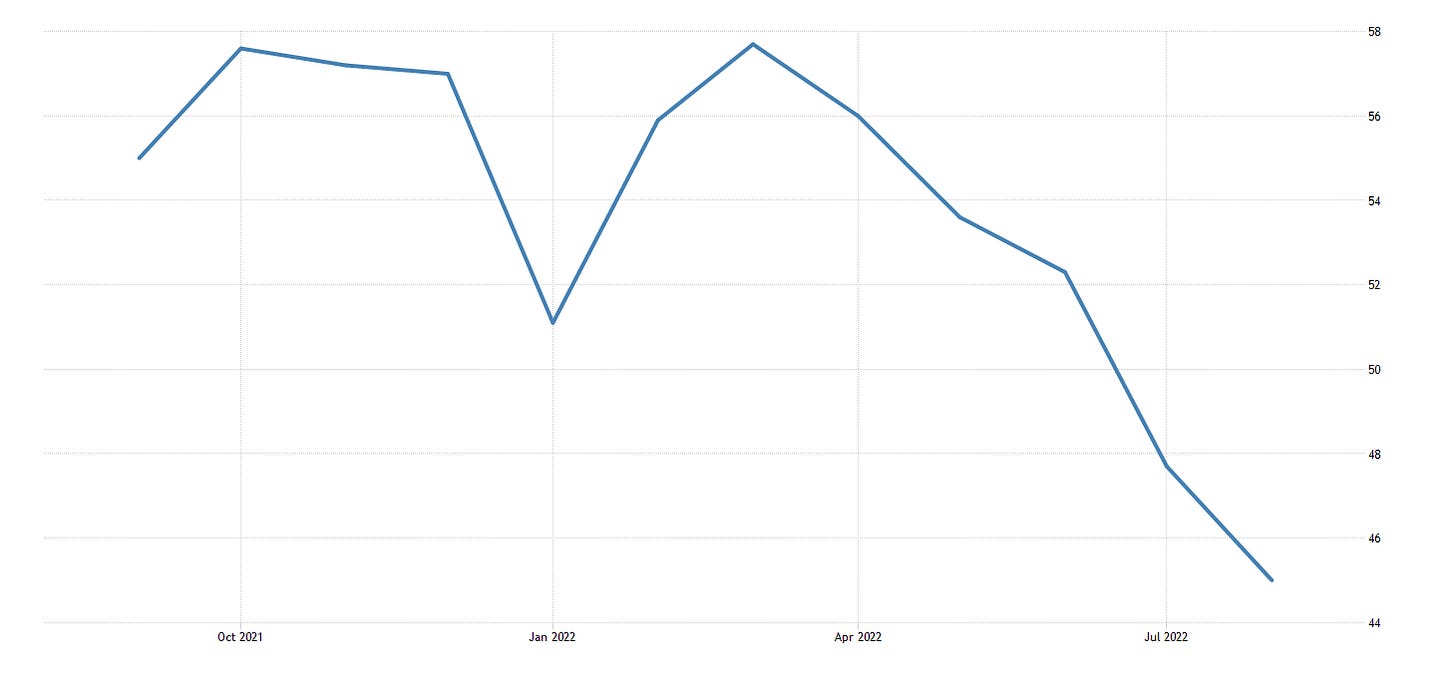

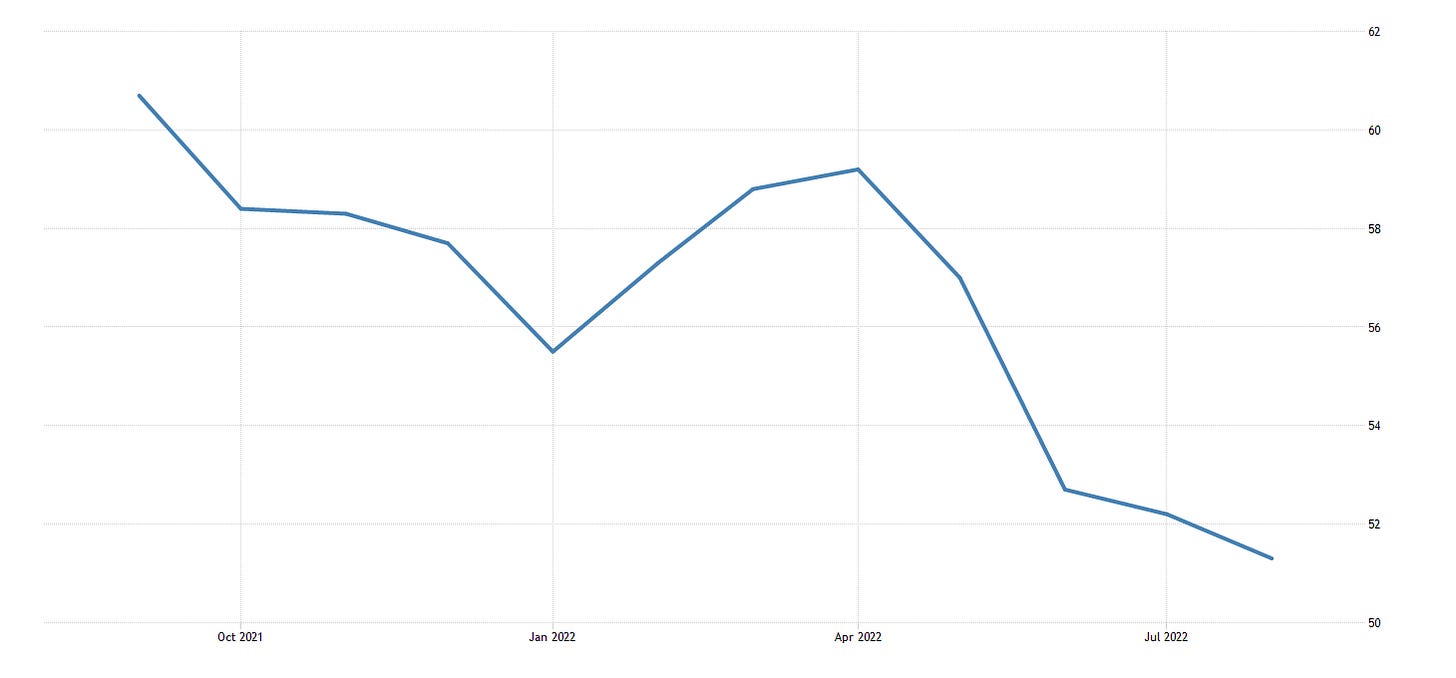

S&P Global’s Composite Purchasing Manager’s Index for August fell further into contraction territory, to 45 from 47.7 in July.

The Services PMI declined to 44.1, and while the Manufacturing PMI remained above the 50 boundary between expansion and contraction, it still posted a decline to 51.3 from 52.2 in July.

For its part, the Philadelphia Federal Reserve’s Manufacturing Business Outlook Survey gave mixed signals:

The diffusion index for current activity returned to positive territory in August after two consecutive negative readings, rising 19 points to 6.2 (see Chart). Most firms (47 percent) reported no change in current activity this month, while the share of firms reporting increases (26 percent) exceeded the share reporting decreases (20 percent). The index for current new orders climbed 20 points but remained negative for the third consecutive month at -5.1, and the current shipments index rose 10 points to 24.8.

The Philly Fed’s Non-Manufacturing Business Outlook Survey showed a general decline in business.

The diffusion index for current general activity at the firm level fell 12 points to -0.1 (see Chart). The firms were evenly split between reporting increases and decreases (29 percent); 38 percent reported no change in activity. The new orders index fell 10 points to -5.9 this month. Almost 21 percent of the firms reported increases in new orders, while 27 percent reported decreases. The sales/revenues index decreased from 9.4 to -2.1. Almost 30 percent of the firms reported increases in sales/revenues (down from 34 percent last month), while 32 percent reported decreases (up from 24 percent). The current regional activity index declined and turned negative at -3.7, its first negative reading since January 2022.

Despite Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s insistence that the US economy is not in recession, recession is exactly what these indicators are signalling—not in the future, but in the present.

The Fed Sees The Same Data But Does Not See The Recession

Amazingly, the entirety of the Federal Reserve looks at these same indicators, this same data, and sees an economy that is slowing down, but not in recession.

That was the assessment of the economy in the Fed’s July FOMC meeting.

Participants noted that indicators of spending and production pointed to less underlying strength in economic activity than was suggested by indicators of labor market activity. With employment growth still strong, the weakening in spending data implied unusually large negative readings on labor productivity growth for the year so far. Participants remarked that the strength of the labor market suggested that economic activity may be stronger than implied by the current GDP data, with several participants raising the possibility that the discrepancy might ultimately be resolved by GDP being revised upward. Several participants also observed, however, that the labor market might not be as tight as some indicators suggested, and they noted that data provided by the payroll processor ADP and employment as reported in the household survey both seemed to imply a softer labor market than that suggested by the still-robust growth in payroll employment as reported in the establishment survey.

It was the assessment of Fed Governor Michelle Bowman in a speech to the CEO & Senior Management Summit on August 6:

My base case is for a pickup in growth during the second half of this year and for moderate growth in 2023. As we learned during the summer and fall of 2021, both GDP and jobs numbers are subject to significant revision, both in subsequent months and then again the next year. From my perspective, had we known at the time about the eventual large upward revisions in last year's employment data, we likely would have significantly accelerated our monetary policy actions. Going forward, we have to consider the possibility of these kinds of revisions when making real-time judgments as policymakers, which includes looking at other kinds of indicators instead of relying too heavily on the data. Taking all of that on board, while the data on economic activity are indeed lower and the view is murky, the evidence on inflation is absolutely clear, which brings me to the implications for monetary policy.

That was Jay Powell’s assessment at his press conference after the July FOMC meeting.

“I do not think the U.S. is currently in a recession and the reason is there are too many areas of the economy that are performing too well,” Powell said at a press conference following the Fed’s decision to raise rates by 0.75 percentage point for a second consecutive time. “This is a very strong labor market ... it doesn’t make sense that the economy would be in a recession with this kind of thing happening.”

This despite two successive quarters of GDP decline—the conventional technical delimiter for a recession.

This despite multiple indicators in July showing deteriorating household finances, shrinking business activity, and at best a problematic labor market.

This despite an ailing real estate sector with collapsing sales amid rising interest rates.

The Fed looks straight into the data—can cannot see the obvious: the US is in a recession which is steadily getting worse.

The Rate Hike Strategy Is Not Working As Planned

Conventional wisdom is undeniably that raising interest rates is the cure for rampant inflation, but at what point does the Fed acknowledge that the “conventional” path is not producing the conventional results? Regardless of the intentions or theoretical underpinnings, the Fed’s rate hikes have had little impact on inflation, but decidedly negative impact on the economy overall—the extent of the impact might be a matter of debate but in no regard can the Fed’s hikes be seen as a net economic positive.

When the conventional wisdom has unconventional—and counterproductive—results, a reappraisal of the conventional wisdom is in order.

If monetary policy is not succeeding in taming inflation, the Federal Reserve should be leading the call for fiscal policy to fill the breech, not fatuously offering bland reassurances that they have the solution in hand.

If rate hikes are not having the desired impact, the Federal Reserve should be tabling future rate hikes and finding alternative means for shrinking the money supply and bringing down inflation.

The Fed might yet seek unconventional approaches to corralling inflation, but to do so it has to admit that its read on inflation and the economy has been wrong since the pandemic if not before. If the Federal Reserve is preparing to make such an admission they have concealed it well.

In the face of the Fed’s complete denial of economic reality, the question attending upon Jay Powell’s upcoming Jackson Hole speech is not “what will the Fed do next?” but “how much more damage will the Fed do?”

The answer is likely to be “quite a lot.”

The damage is already baked in the cake. Two (or arguably even three) decades of artificially low interest rates have produced unsustainable levels of debt throughout the economy (both in the public and private sectors) and have enabled the FedGov to spend far beyond its means. The politicians in both parties will not stop deficit spending until the bond market forces them to with much higher rates. But if/when that happens, it will create a lot of damage too.

There's a similarity between "defund the police" and markets.

If the police are defunded, it would correspond to a rise in vigilantism.

Markets already have vigilantes. Fortunately they do only monetary damage.

The problem in both cases is that society should make up its mind: Police or vigilantes?

The Fed or "bond vigilantes?

Life would be smoother for all of us if we could only decide. And stick with it.