Has China's "Lehman Brothers" Moment Arrived?

China's Financial Markets Are Deteriorating Rapidly

The past week has not been kind to China’s financial markets.

First came the news that real estate developer Country Garden missed required interest payments on two dollar-denominated bonds.

The latest major industry player to get into trouble is Country Garden, once China’s largest developer.

Shares in the construction giant have plunged 16% in Hong Kong since Tuesday, after reports by Reuters and Chinese media that it missed interest payments on two US dollar-denominated bonds. Several of Country Garden’s yuan-denominated bonds were suspended from trading in Shanghai and Shenzhen on Tuesday after they dropped by more than 20%.

Then came the grim reality of Country Garden’s results for the first half of 2023: huge losses and deteriorating margins.

Country Garden Holdings, one of China’s biggest property developers by sales, has warned of a large net loss in the first half due to impairment on property projects and declining profit margins in its real estate business.

The Chinese property developer expects to record a net loss ranging between 45 billion yuan (US$6.25 billion) and 55 billion yuan for the first six months of 2023, swinging from a net profit of around 1.91 billion yuan in the same period last year, according to a late filing to the Hong Kong stock exchange on Thursday.

The very next day came reports that a major private wealth manager, Zhongzhi Enterprises, missed scheduled payments on multiple wealth management products.

One of China’s largest private wealth managers is triggering fresh anxiety about the health of the country’s shadow banking industry after missing payments on multiple high-yield products.

Three firms said late Friday they failed to receive payments on products issued by companies linked to Zhongzhi Enterprise Group Co., which has about 1 trillion yuan ($138 billion) in assets under management.

And just like that, China’s financial markets were made to look like a house of cards about to collapse.

Thus comes the question: Has China’s “Lehman Brothers” moment arrived?

Before we answer that question, a few points about the infamous collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 which marked the start of the Great Financial Crisis should be reiterated:

Lehman Brothers collapse was not a “moment”, but a somewhat drawn out decline that began in 2007 and steadily progressed towards a brutal denouement in September 20081.

Lehman Brothers woes were centered over a hugely overplayed mortgage securitization strategy, which boomeranged badly when the subprime mortgage markets collapsed in 2005-20072.

Six months before Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, Bear Stearns failed in pretty much the same fashion over the same mortgage securitization strategy—with the difference being that regulators orchestrated a bailout/takeover of Bear Stearns but declined to do so for Lehman Brothers3.

These points are significant as they clarify the sort of market dynamics we should see if we are seeing a Lehman Brothers-style market implosion unfolding in China right now.

Certainly China’s real estate woes qualify as a “drawn out” decline. With Evergrande’s ongoing collapse having started in 2021, and real estate developers having encountered financing challenges since Xi Jinping’s “Three Red Lines” policy in 2020, Country Garden’s missed bond payments and deluge of red ink comes at the end of a very long and drawn out property crisis.

Country Gardens’ problems are largely of a piece with those that brought down Evergrande: too much leverage, too few completed housing projects, and a housing market that is continuing to spiral down.

The extent of China’s housing market woes was driven home earlier this week when National Bureau of Statistics data was released showing that home prices dropped nationwide in July for the first time this year.

Prices fell 0.2% month-on-month on a nationwide basis and 0.1% year-on-year, according to Reuters calculations based on National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data.

But the picture is far worse outside of the country's megacities like Shanghai and Beijing. Average new home prices in the 35 smallest cities surveyed by NBS fell for the 17th straight month in June on a year-on-year basis.

The housing market contraction is both the cause and the consequence of developers’ financial problems, as developers’ deteriorating finances have caused potential homebuyers to lose confidence in developers’ ability to deliver housing projects, crimping sales, resulting in further financial deterioration, leading to even less homebuyer confidence.

The downturn has left the property sector caught in a vicious cycle, after an earlier government campaign aimed at getting developers to deleverage caused housing purchases to slump. That crimped the cash flow of builders, leading to a record amount of defaults.

Unprecedented protests broke out across cities last year as builders ran out of cash to complete and deliver apartments to buyers, spurring policymakers to intervene. The Communist Party pledged further easing of property measures following its Politburo meeting in late July.

With Evergrande’s collapse having preceded Country Garden’s current crisis by nearly two years, and with several other developers besides having had problems since, we certainly have in Country Garden the outline of what could become a major financial and banking crisis for China which is quite similar to the early phases of the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. At a minimum, Country Gardens certainly “looks” like a Lehman Brothers moment.

Giving the crisis its own “Chinese characteristics” is the concurrent financial stumbles of Zhongzhi Enterprises. While there is no apparent direct linkage between Country Garden and Zhongzhi, or between Country Garden’s problems and Zhongzhi’s missed payments, real estate is one of the major investment areas in which private wealth management companies in China focus.

What are these trust companies?

They are loosely regulated firms that pool household savings to offer loans and invest in real estate, stocks, bonds and commodities. No other Chinese financial companies operate across all of these asset classes. The sector was once seen as a safe place for wealthy Chinese to park their money for hefty returns. But trust firms have defaulted on billions of dollars of investment products in recent years and the industry has shrunk by about 20% from its peak in 2017, when regulators began clamping down on the nation’s shadow-banking excesses.

Accordingly, Zhongzhi’s financing difficulties are, in the eyes of the corporate media at least, a form of “contagion” ultimately catalyzed by the property sector’s ongoing crisis.

The liquidity challenges underscore how troubles in the property sector, and China’s weakening economy, are now spreading deeper into to the financial sector. Many trust products are backed by real estate projects run by troubled developers such as China Evergrande Group.

Zhongrong is among the biggest firms in the country’s $2.9 trillion trust industry, which pools savings from wealthy households and corporate clients to make loans and invest in real estate, stocks, bonds and commodities. The firm has 270 high-yield products totaling 39.5 billion yuan ($5.4 billion) due this year, according to data provider Use Trust.

Zhongzhi’s troubles are thus an extremely unsettling indication of how far beyond just the real estate sector the fallout from a Country Garden collapse could spread.

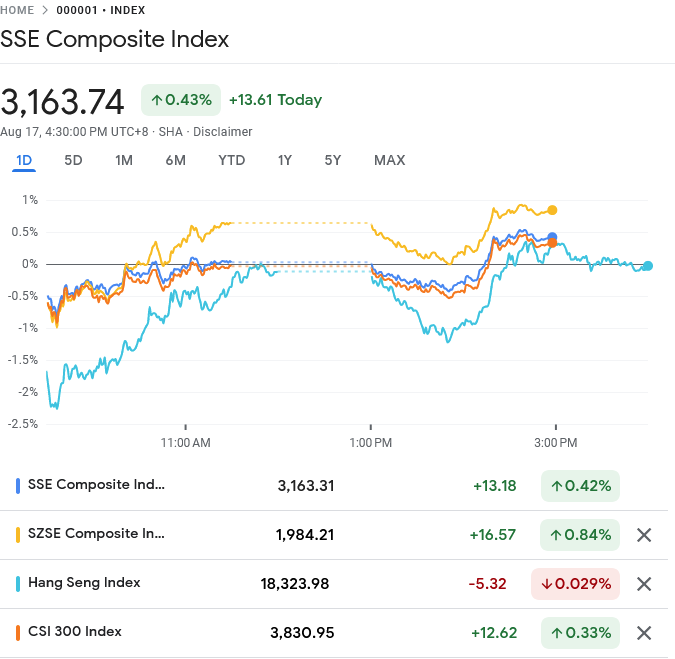

China’s stock markets certainly are not in disagreement with the Lehman Brothers comparison. Over the past week all of China’s major indices have had significant drops.

At a minimum, Country Garden and Zhongzhi are not “good news” for Chinese finance.

Adding to the raft of bad news has been the latest release of Chinese economic data, which, among other things, shows home prices in China resuming 2022’s freefall, dropping 0.2% month on month between June and July.

Without at least stability in home prices, developers such as Country Garden are facing a monumental challenge in restructuring their mountain of debt.

Beijing certainly seems to agree, as the People’s Bank of China opted on Tuesday to lower a benchmark interest rate 15 basis points to provide support for banking and new loans.

The People's Bank of China unexpectedly reduced the one-year medium-term lending facility rates by 15 basis points to 2.5% Tuesday, signaling a proactive stance to support its economy against mounting challenges.

The decision comes as China grapples with the dual threats of a deepening property crisis and sluggish consumer spending and follows a series of disappointing economic indicators.

The cut in the MLF rate is the first one this year, and the sixth one since the beginning of 2020.

The interest rate cut is the latest move by Beijing to blunt the ongoing erosion of China’s investment in real estate, which has been shrinking steadily since the beginning of 2022.

After shedding 10% in 2022, China’s real estate sector is on track shed even more in 2023, indicating that the collapse of China’s property markets is still far from over.

The continued contraction of China’s real estate sector is also leading to anticipation that the surprise rate cut on the one-year medium-term lending facility will not be sufficient to alter the downward trajectory of Chinese investments.

China surprised by cutting its one-year medium-term lending facility (MLF) rates by 15bp to 2.50% today to give a jolt to its economy that has not only completely missed the expectation of a great post-Covid recovery, but that deals with deepening property crisis, morose consumer, and investor sentiment – which is worsened by Country Garden crisis and missed payments from the finance giant Zhongzhi Enterprises. Data-wise, things looked as worrying as we expected them to look when China released its latest set of economic data today. Growth in industrial production unexpectedly dipped to 3.7%, retail sales unexpectedly fell to 2.5%, unemployment worsened, while growth in fixed investments dropped further. Foreign investment in China fell to the lowest levels since 1998, and the 13F filings showed that Big Short’s Michael Burry already exited Alibaba and JD.com, just months after increasing his exposure to these Chinese tech giants. People’s Bank of China’s (PBoC) surprise rate cut will hardly reverse appetite for Chinese investments as meaningful fiscal stimulus becomes necessary to stop halting.

Much like Lehman Brothers in 2008, Country Garden’s woes are a harbinger that still more bad news awaits China’s developers—more bad news, and more interesting times.

Another indicator of Beijing’s growing concern over the developments at Zhonghzhi in particular has been the formation last month of a special task force specifically to look into Zhonghzhi’s finances.

The National Financial Regulatory Administration established a working group last month to gauge the outstanding debt and risks at one of the main financing arms of Beijing-based Zhongzhi, which oversees more than 1 trillion yuan ($138 billion) of assets, according to people familiar with the matter, who asked not to be identified discussing a private matter.

The regulator required Zhongrong International Trust Co. to report its plans for future payments and available assets that can be disposed of to deal with the liquidity crunch, said the people. Nearly half of the funds raised by Zhongrong were funneled to its parent or affiliated units, one of the people said.

The task force underscores the extent to which officials have become alarmed by the situation at Zhongzhi, whose troubles have surged to the fore in recent days after several of its corporate clients disclosed overdue trust payments. The episode has put a fresh spotlight on China’s $2.9 trillion trust industry, which combines characteristics of commercial and investment banking, private equity and wealth management.

Zhongzhi’s liquidity crisis is also sparking fresh public protests by Chinese investors, angry over a the shadow bank’s growing list of missed payments on its investment products.

Angry investors in China protested outside a shadow bank on Wednesday, after it missed payments on dozens of investment products. This rare show of public anger points to serious trouble amid debt and housing distress in the world's second-largest economy.

Zhongzhi’s turmoil echoes the public outcry last year, when homebuyers in several provinces turned out en masse to protests the lack of delivery of completed homes and housing projects by home developers.

With each successive expansion of the crisis, China’s banks have come under increasing stress. At the same time, the crisis in real estate is colliding head-on with a rural banking scandal in Henan province, where some $6 billion worth of bank deposits have gone missing—and the depositors want their money back.

Zhongzhi highlights a particular problem within the Chinese economy: every economic dislocation has potential political overtones, as people have little recourse to any other means of remedy short of public protests.

We saw this last fall when the Chinese people ran out of patience with the Zero COVID lockdowns.

We saw this last summer when the mortgage boycotts threatened to unravel the CCP’s grip on power, eventually forcing the abandonment of Xi Jinping’s “three red lines”.

So embedded is the Chinese state within the Chinese economy that, ultimately, all economic crises hinge on what Beijing does or does not do.

Is Country Garden a Lehman Brothers moment with Chinese characteristics? Is Zhongzhi?

Certainly the financial media is aware of the parallels, with “Lehman” appearing with increasing frequency in reports on China.

Certainly Beijing fears either might be, as it is somewhat belatedly moving to calm China’s increasingly jittery markets.

However, while China’s financial markets might be jittery, they are not yet panicked, having staged a small recovery rally over the past day after having spent the bulk of the previous week on the decline.

What is clear is that China’s economy has never regained its footing post-COVID. It has stumbled and lurched from one crisis to the next, from one disappointment to the next.

Country Garden may or may not be China’s “Lehman Brothers” moment. Zhongzhi may or may not be China’s “Lehman Brothers” moment. While the comparisons are there, it is still too soon to say definitively that China’s economy is set to begin a cataclysmic market meltdown after the fashion of the Great Financial Crisis.

What is not too soon to say is that, with or without a “Lehman Brothers” moment, China’s economy will continue to lurch and sputter from crisis to crisis, from market failure to market failure, for the foreseeable future. China’s economy may not crash in spectacular fashion, but only because it will slowly crumble instead.

How would you compare China's economy with America's in terms of the immediate future, especially with the UN Lawyer's continual successes (no matter how unconstitutional).

Serves 'em right. Though I do feel sorry for the rank and file citizens who are stuck living under that regime.