Inflation, Deflation, Or Both?

The Mixed And Muddled Signals On Future Price Movements

Longtime readers are no doubt aware of my recent predictions that consumer price inflation is in the process of heating up once more.

Longtime readers are also aware that I bolster such predictions with a series of observations drawn from various publicly available data sets.

Yet that should not be taken to imply that all the indicators are pointing to inflation. They aren’t.

There are more than a few economic indicators which suggest that the US could be headed into a period of protracted consumer price deflation rather than inflation. It would be folly to ignore the presence of these contrarian indicators, as they may prove to be the most accurate. Excluding the contrarian view is how corporate media destroyed its own credibility.

As I choose to be honestly wrong rather than deceptively right, let’s explore the possible indicators of coming deflation in the US economy.

To begin, we should understand that core consumer price inflation has demonstrably accelerated in recent months. That data shows that unequivocally.

The data also shows within core inflation service price inflation has been heating up.

At least these subcomponents of overall inflation have been trending higher since the summer. On this level at least, we are already seeing higher consumer price inflation.

Moreover, during September there was a clear increase in several of the commodity trading indices, implying that the prices of most production inputs was set to increase.

At the same time, crude oil prices had demonstrably bottomed out in early September and spent the rest of the month trending upward.

All of these signals are clear indicators that consumer prices are heating up and are likely to continue heating up.

How, then, do we get to contemplating a future of consumer price deflation?

Let’s look at some of the rest of the data.

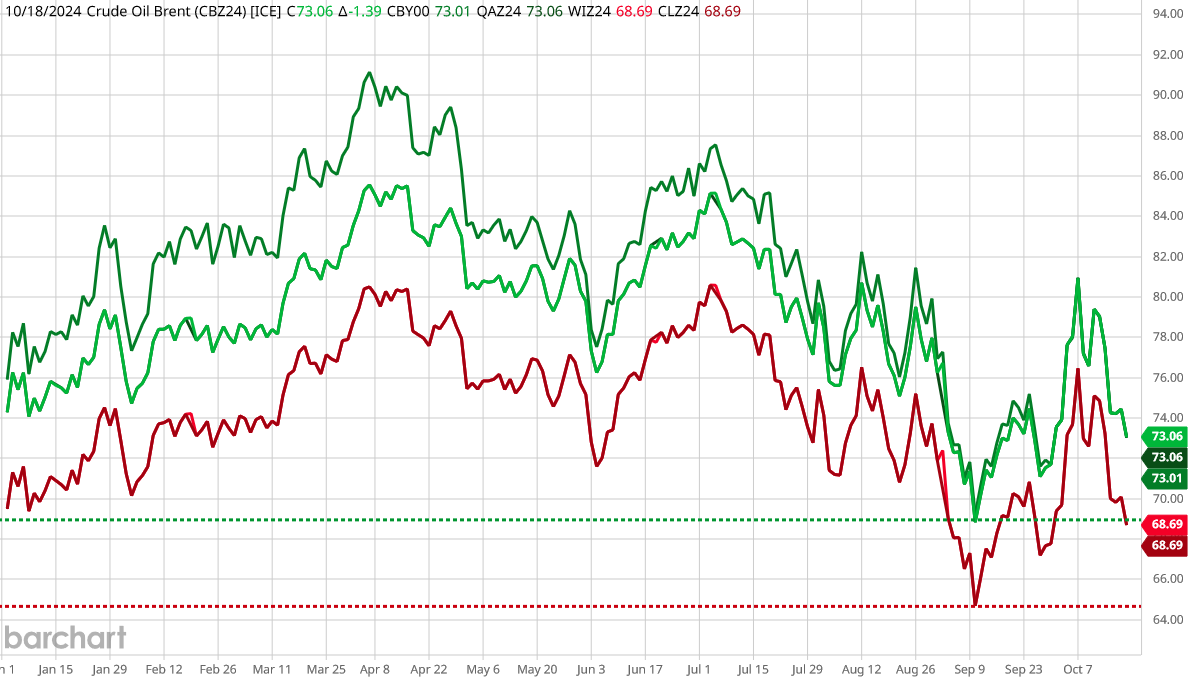

The first data point we have to look at is that oil did not continue its upward trend, but reversed in early October, and is now lower than it was on September 1.

It’s worth noting that energy prices did not even sustain a new floor price above the September 1 level. While it has not yet reached the floor level reached in early September, we should not rule that out.

Moreover, we should also recognize that even that floor price was substantially below the floor prices temporarily established earlier in 2024.

We have seen the September floor price established beginning in late summer 2022 and reaffirmed throughout 2023.

Should that floor be breached in the coming weeks and months, then energy markets could be looking at a protracted period of energy price deflation.

Even if the floor is not breached, the inability of oil prices to sustain levels above the September 1 level suggests that the capacity of energy prices to contribute to long term general price inflation is problematic. Energy prices have to themselves be rising for there to be substantial energy price inflation, and a hard ceiling price limits the extent to which oil prices will actually be rising going forward.

If the floor price is reaffirmed, then we can look forward to some level of energy price inflation in coming months. If the ceiling price is also reaffirmed, however, that energy price inflation is effectively capped.

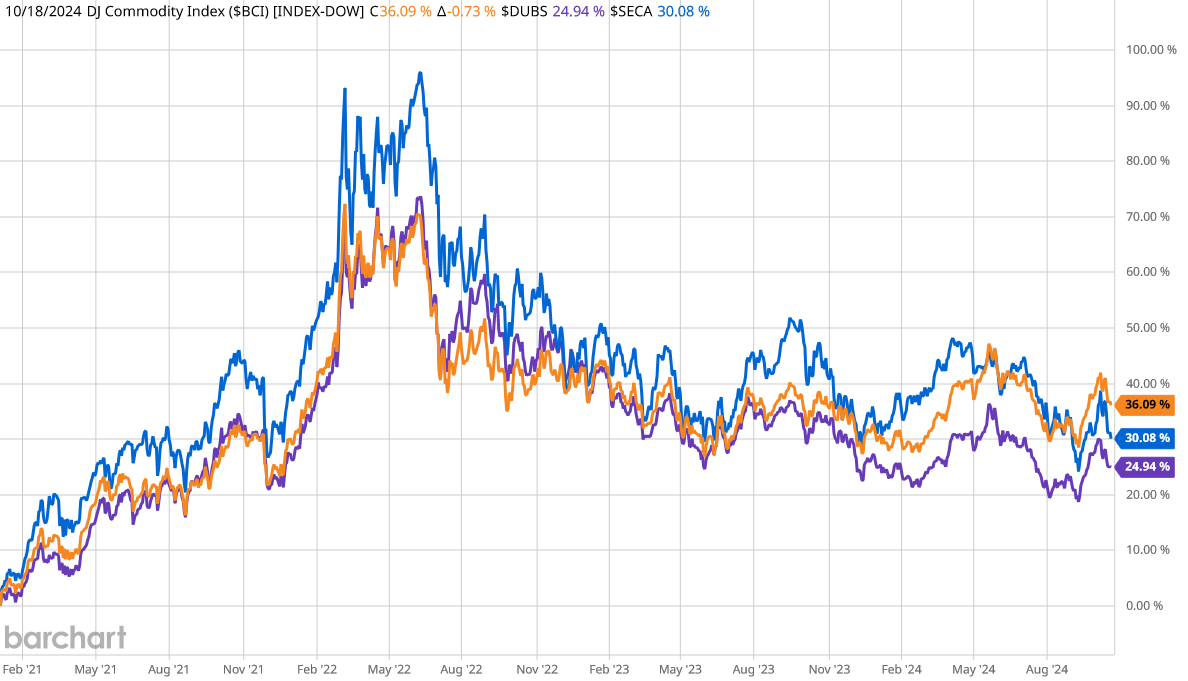

The patterns we have seen in market energy prices are reflected in broader commodity prices. September’s inflationary trend has reverted to a disinflationary/deflationary trend in October.

Nor is this a momentary correlation. If we zoom out to include all of 2024 we see commodity prices following energy pricing patters quite closely.

Zooming out to the start of the (Biden-)Harris Administration, we see commodity prices following oil price trends quite closely even over the longer term.

Undoubtedly, this trend is in part because oil prices themselves factor into the commodity indices, yet at the same time if oil is overweight in influencing commodity price indices, other commodities are necessarily underweight. If commodity trends are driven mainly by oil, then they are not driven by other commodities such as copper, steel, and agricultural products.

Consequently, both in the specific instance of oil and in the general market for traded commodities, we see prices having peaked in 2022, after which a steadh deflationary trend was established. While that trend began to show signs of bottoming out in 2023, that trend has not sustained a reveral for more than a few months.

The overall trend for commodities is still deflationary, although the magnitude of the deflation may be reduced in coming months.

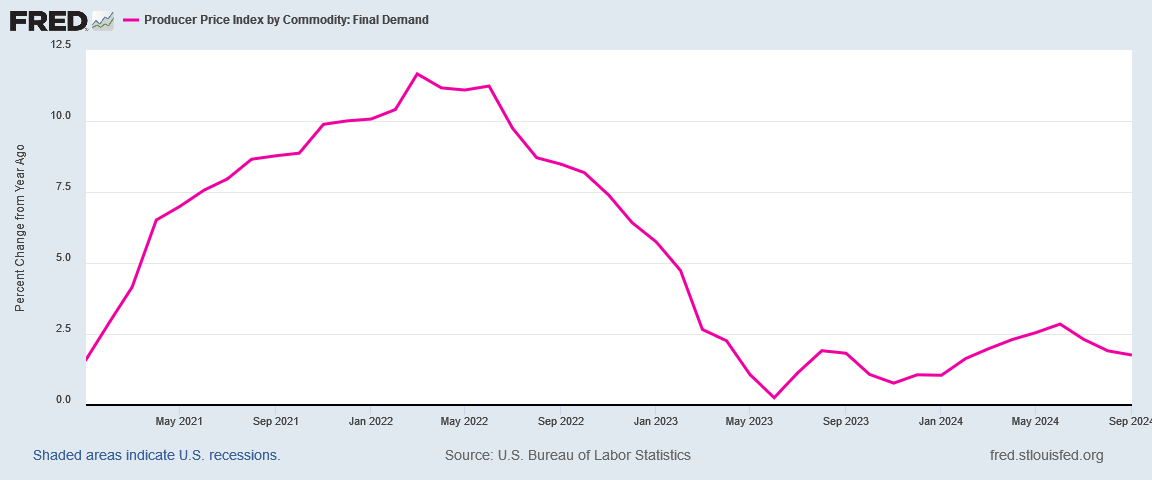

We see another sign of coming consumer price deflation in the Producer Price Index for Intermediate Demand.

Not only have we seen outright deflation among intermediate goods—goods which will become inputs farther along in the production process—in August and September, even before that the overall trend in the PPI for Intermediate Demand has been steady disinflation which finally tipped over into outright deflation.

The disinflation trend in PPI for Intermediate Demand is a trend which began in early 2022 and has broadly proceeded since.

As we can see from the underlying indices themselves, the deflationary trend for intermediate demand output began also in early 2022.

As I have noted multiple times before, the PPI is widely viewed as an early predictor of what the Consumer Price Index is likely to do. If we are seeing deflationary impulses from the PPI for Intermedieate demand, there is a clear deflationary pulse begin sent into consumer markets in the form of cheaper inputs, which in turn will produce a downward pressure on consumer prices.

Even the PPI for Final Demand: Goods printed outright deflation in September.

While the forces are always subject to change, at least in September the pricing pressure demonstrated by the PPI for Final Demand: Goods is downward, not upward.

When we look at the year on year precent changes in the PPI, we see similar downward price pressures, albeit still in the realm of disinflation rather than outright deflation.

In absolute terms, this downward price pressure expresses itself as a general plateau effect in the underlying index.

Despite rising consumer price inflation, the Producer Price Index displays several indicators that suggests we should be forecasting future deflation, in a few months if not right away.

We see deflation signals in other non-price data as well.

Industrial output in manufacturing most recently peaked in late 2022, and has with varying rates been in a deflationary trend ever since.

Even among non-consumer goods, the only category that shows a significant and steady upward trend is defense goods—undoubtedly a reflection of military aid to Ukraine and Israel.

Construction and general business supplies both peaked in 2022 and have been on a downward trend since.

Also at varying rates, we see a similar trend in industrial production for equipment as well.

Decreases in industrial production are by definition deflation indicators. An economy that produces less is exactly what deflation is.

An economy that has people working less in manufacturing is also a prime exemplar of a deflating economy—and that is exactly what the US economy has been since at least 2021, with average weekly hours of manufacturing workers on a near constant decline.

While in recent years there has been a recovery in manufacturing employment, that peaked in 2023 and has also begun to trend down.

While the growth in manufacturing employment in the early years of the (Biden-)Harris Administration looks impressive, we should remember that the bulk of this was merely recovering the manufacturing jobs that existed at the start of the Pandemic Panic.

In absolute terms, the Trump era was far better for manufacturing employment.

Are these indicators which are flashing “deflation” more influential and more dispositive than the indicators flashing “inflation”?

That is possible.

It is also possible that we may end up with an intensifying of a trend we are seeing already: inflation within some goods and across most services, and deflation in much industrial output and production of consumer goods.

I have argued in the past that a combination of inflation and deflation, of strong downward price pressures and strong upward price pressures, is both what we have experienced and what we are likely to experience in the future.

Given that we are seeing both inflationary indicators and deflationary indicators, a “stagflation” scenario may be the way to resolve all the indicators into a single economic forecast.

Whether stagflation is a less dire outlook than deflation would largely be a matter of conjecture and one’s particular economic perspective. Stagflation would from all perspectives be a net negative in terms of economic evolution, as it translates into increasing distortions in prices among various consumer goods and decreasing output of several goods, some industrial and some consumer.

Both a stagflation scenario and an outright deflation scenario translate into the US economy experiencing a “lost decade”. It would be the first such acknowledged event since the Great Depression of the 1930s (while some economic models would make the decade after the 2008 Great Financial Crisis into another lost decade, that assessment is still fairly problematic.

Additionally, we must always remember that what goes up must come down. We could very well see rising consumer price inflation for October, and even for the rest of 2024, only to see that give way towards increasing deflation and/or stagnation beginning in early 2025. Such scenarios are in no way outside the realm of possibility.

In the short term I still expect inflation to rise somewhat for October. Oil prices are coming down but they have not yet shown the magnitude of even the September price drops. A diminishing magnitude of oil price decline equates to diminishing influence of energy prices in the overall CPI.

However, over the longer term, and even in the medium term (i.e., from early 2025 onward), I would not be a bit surprised to see deflation make its appearance, and then stick with us for a while.

Whether the forecast is inflation, stagflation, or deflation, however, none of the three broad predictions constitutes any sort of confidence in the future of the US economy. That part should come as no surprise. I have been arguing for months that the state of the US economy is not good, and that it has been getting worse. No matter which scenario we get—inflation, stagflation, or deflation—that remains the trajectory of the US economy.

Will we have inflation, deflation, or both? The answer may very well be first we will have the one, then the other, and in the end we will wind up with both.

That’s not a good thing.

Peter, I love how your mind works. In all of the mixed and muddled signals, you zero in on just the right indicators to give us a clearer picture. Most analysts have an agenda they want to prove - while you just want to get to the truth. This makes your analysis priceless!

And your conclusions match up with common-sense observations. If people have to spend more on the obligatory purchases, they will likely cut back on discretionary purchases. In terms of supply and demand, less demand for, say, clothes - a discretionary purchase - will put pressure to lower the prices on clothes, out of competition. I’m already reading predictions of a bleak Holiday season from retailers, and there have been many articles about how consumer credit-card debt is pretty much maxed out. So the real-world picture of higher prices on some things (rent, health care, etc.) plus desperate producers of discretionary goods competing to stay in the game, will result in stagflation. I was majoring in economics during the stagflation of the 70s, so I remember well the effects, along with the puzzlement of the economics profession as they tried to figure out solutions.

The wild cards next year will be: how the unraveling of China’s economy will affect us, and how the policies of the post-election era (Trump’s tariffs, or Kamala’s insanities) also will affect us. So maybe stagflation for the near future, then WHOOPS!