Interest Rates Are Already Falling, Even Before The Fed Cuts

Will Wall Street Steal The Fed's 2024 Thunder?

Wall Street is convinced the Federal Reserve is going to cut interest rates in 2024, so it is decided to treat itself to lower interest rates for Christmas.

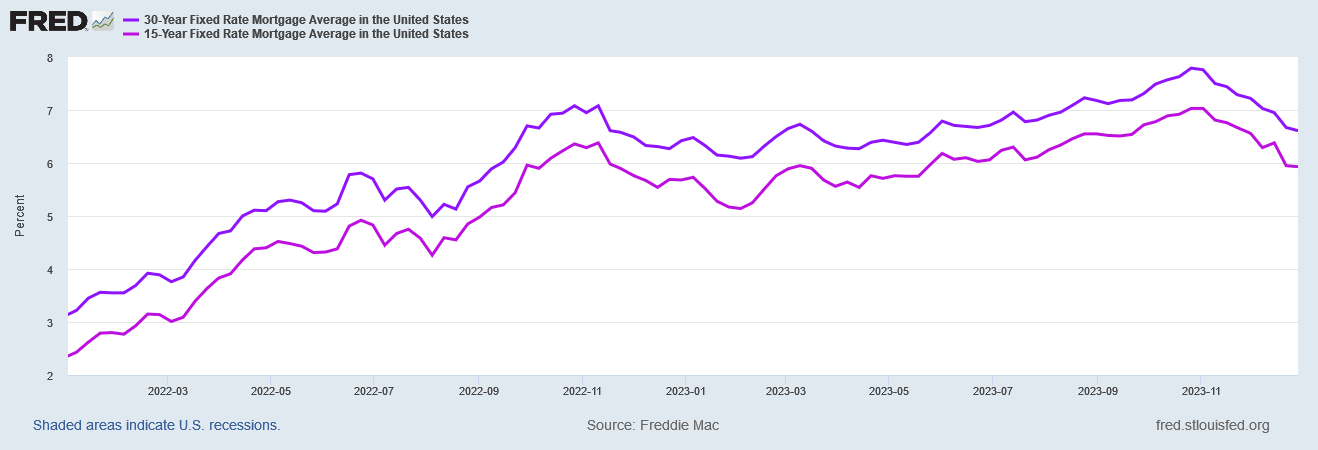

The most notable decline of late has come in mortgage interest rates, where last week they continued the downward trend they have been on for the past several weeks, printing at their lowest level since May.

Mortgage rates are down again this week — the lowest level since May.

The rate on the 30-year fixed mortgage declined to 6.61% from 6.67% the week prior, according to data released by Freddie Mac on Thursday. Rates fell for the ninth consecutive week. Overall, rates have fallen over a full point from 7.79% in October.

The media consensus is that Wall Street is anticipating rates moving substantially lower in 2024 based on the Fed’s expected rate cuts, and so Wall Street is responding by moving rates down now. For prospective homebuyers, the lower mortgage rates are a welcome drop in overall home prices, after a year when home ownership was made increasingly unaffordable.

The latest figure is still above last year’s average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage rate of 6.42 percent, but the downward trend is a welcome sign for homebuyers who have weathered a dismal housing market.

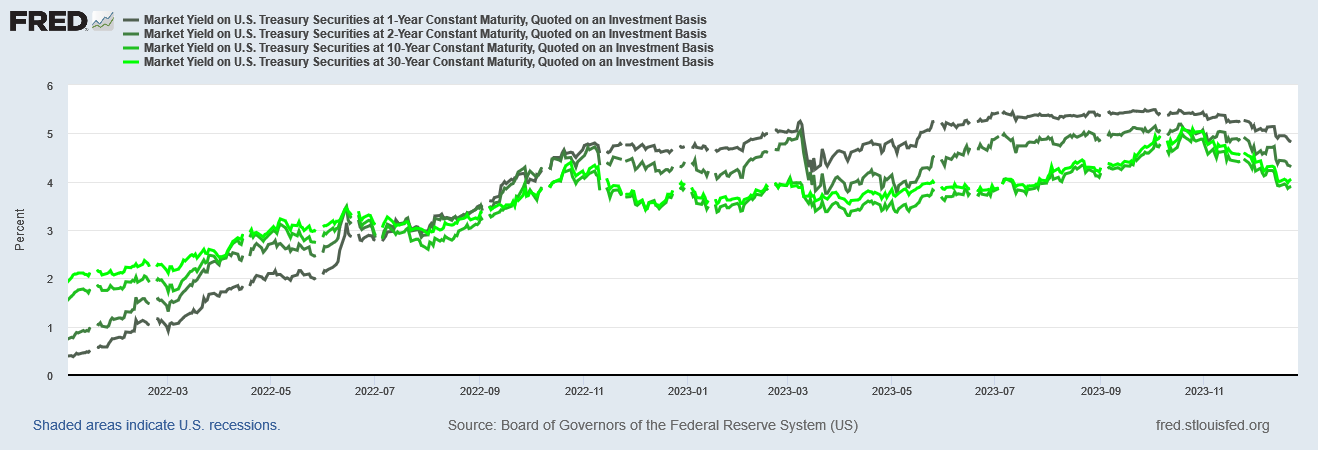

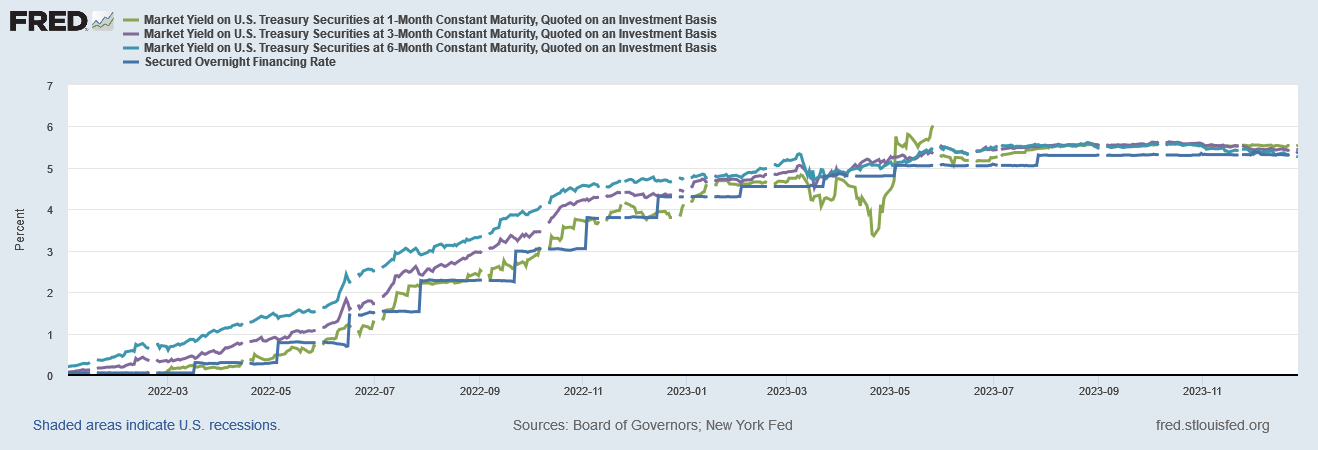

However, it is not merely mortgage interest rates which are declining. Long-term Treasury yields are also moving south, and even the shorter term yields are just treading water.

In short, interest rates are once again moving in whatever direction Wall Street wills, without regard for the Fed’s strategy or positioning on either interest rates or inflation.

Is Wall Street about to steal the Fed’s anticipated 2024 rate cut thunder? That is a distinct possibility, which would make Fed policy for 2024 even more chaotic and reactive than it has been in 2023—not a good look for an entity whose reason for being centers on stability and order rather than chaos.

Mortgage rates are at the moment particularly noteworthy, because after a brief peak near 8% in October, they have dropped by more than a percentage point.

Perhaps not coincidentally, long term Treasury yields abruptly stopped their recent rises and began declining at the same time, and have also managed to come down by nearly a full percentage point.

Short term yields, on the other hand, were not nearly so volatile, largely holding steady through the end of 2023.

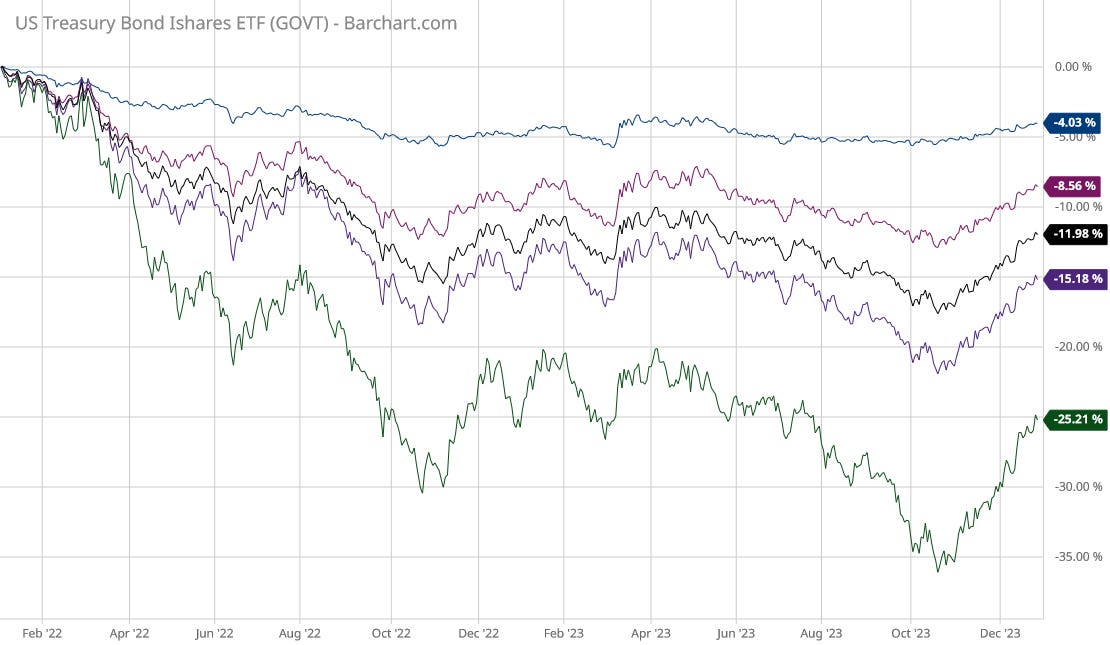

Wall Street has greeted these interest rate movements with something akin to a sigh of relief, as the shrinking yields have allowed existing securities portfolios to recover a significant portion of their value.

As the various Treasury-based Exchange Traded Funds illustrate, beginning at about the same time that interest rates began moving down across the board, ETF valuations began moving up, with the ETFs in longer term yields showing the greatest price appreciation and the shortest term valuations largely just treading water—price movements which match interest rate movements almost exactly.

However, Wall Street hopium on interest rates is only part of the narrative at play here. The Federal Reserve has indeed been fueling that speculation on future interest rate cuts, but at the same time the FOMC opted to stand pat on the federal funds rate for the third straight meeting. The federal funds rate cuts may happen this year, but at the moment those are projections only. The Fed’s now-reflexive “data dependent” policies mean they will not cut until Jay Powell decides it is time to cut.

We should also note that the Fed is also projecting a steep drop off in economic growth both for the final quarter of 2023 and for 2024, looking back at Powell’s remarks after the FOMC rate announcement.

I will have more to say about monetary policy after briefly reviewing economic developments. Recent indicators suggest that growth of economic activity has slowed substantially from the outsized pace seen in the third quarter. Even so, GDP is on track to expand around 2.5% for the year as a whole, bolstered by strong consumer demand, as well as improving supply conditions.

After picking up somewhat over the summer, activity in the housing sector has flattened out and remains well below the levels of a year ago, largely reflecting higher mortgage rates. Higher interest rates also appear to be weighing on business fixed investment. In our summary of economic projections, committee participants revised up their assessments of GDP growth this year but expect growth to cool with a median projection falling to 1.4% next year.

As I pointed out at the time, the Fed is anticipating an “evolution” of the US economy to substantially less growth.

Let those numbers sink in: if we accept the 5.2% GDP growth in the third quarter published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the Fed is projecting GDP growth for the entire year to be roughly half that percentage, and next year’s GDP growth to be half again from this year’s.

In any economy, those are some pretty dramatic dropoffs in economic performance.

So once again Wall Street is heralding a lessening of economic growth (and arguably a lessening of economic activity) for the United States as a good thing, because of what it means for the Fed’s stance on interest rates. “Good bad news” still reigns supreme on Wall Street.

However, once again Wall Street is managing to ignore several disconcerting trends which call into question what the current drop in yields is truly signalling.

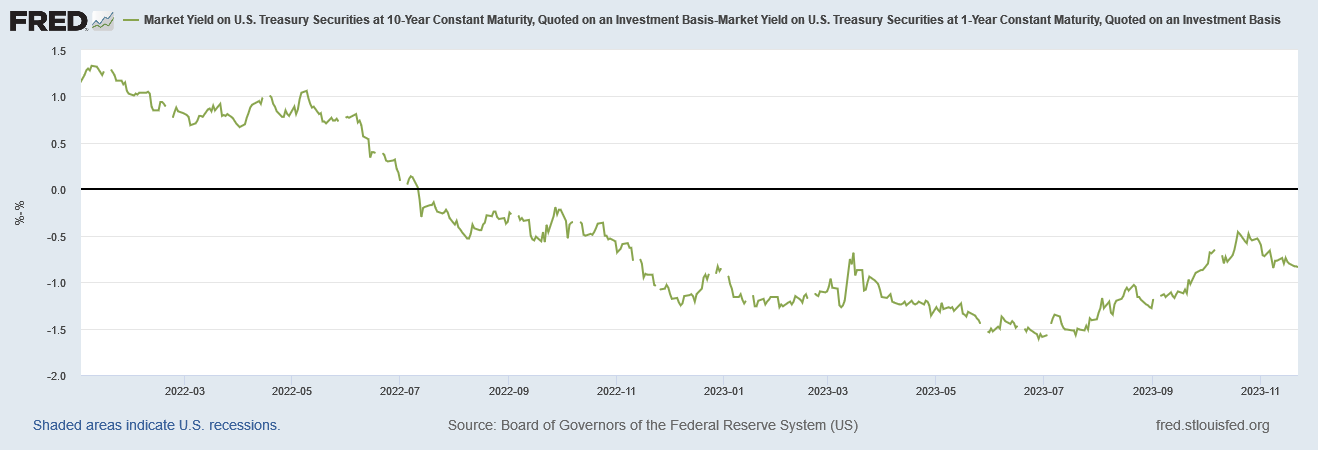

First and foremost, we should note that the interest rate inversions between the 10-Year Treasury and 1-Year Treasury, as well the 30-Year Treasury and the 1-Year Treasury, have increased as the longer term yields have fallen.

These inversions have historically been taken as recession warnings, but during the current Fed rate hike cycle, they’ve been more indicative of the Fed gaming yields by trimming its balance sheet holdings of shorter-term securities while continuing to add longer-term assets.

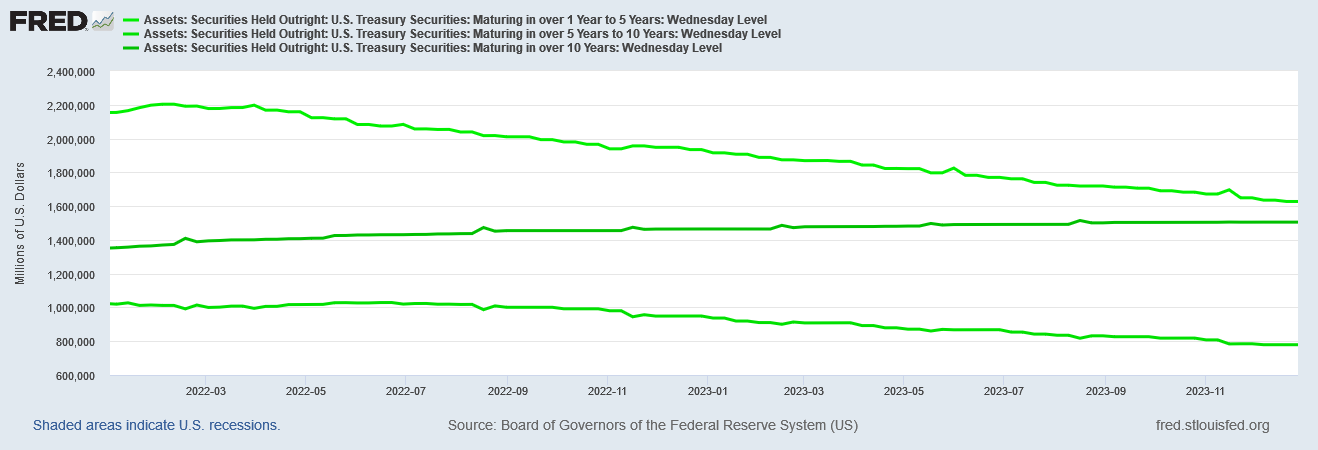

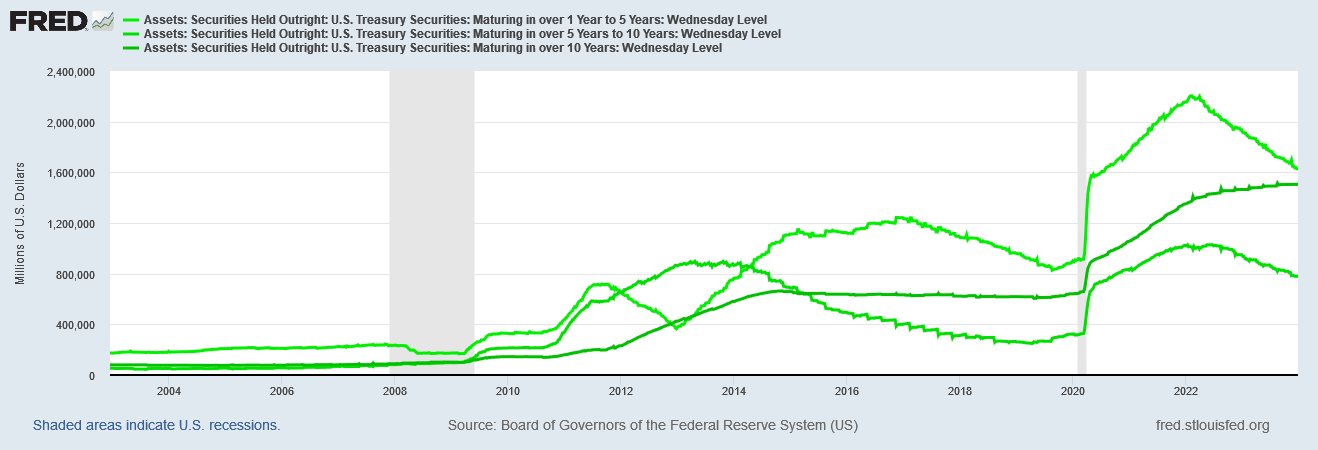

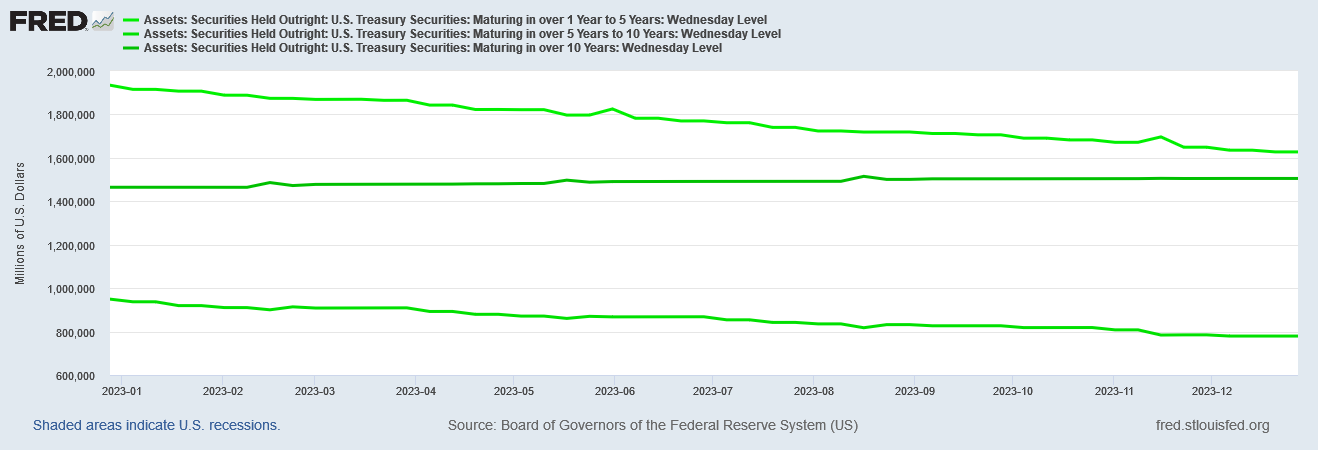

As of December 20, the Fed’s balance sheet is approaching holding more securities with maturities over 10 years than securities with maturities in the 1-5 year range.

That is an evolution on the Fed’s balance sheet which has not happened but once (and only for a moment) in over 20 years.

The Federal Reserve has never been this heavily weighted in longer term maturities than now, and current trends show them getting even more heavily weighted.

However, while the Fed has been rolling off shorter term assets more rapidly than longer term assets, beginning in December, holdings with maturities greater than 10 years also began to decline, albeit only incrementally.

Given that the Fed trimming its shorter-term holdings has been a significant factor in shorter-term yield rises, the drop-off in longer term assets by rights should suggest that longer-term yields would be rising, not falling. The Fed trimming its portfolio means the Fed is trimming its purchases of longer term Treasuries which means the Fed is curtailing demand for these same Treasuries. By rights, yields should be going up, not down.

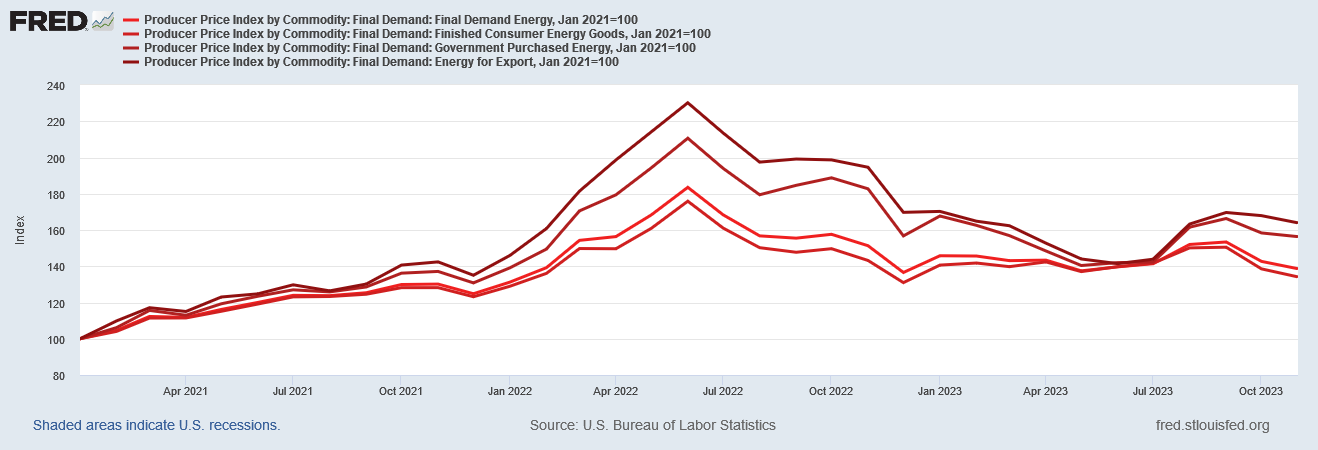

We do well to remember at this juncture that November’s Producer Price Index data was showing significant deflation across the whole of the economy.

The primary cause for the pricing downturn has been, of course, falling energy prices.

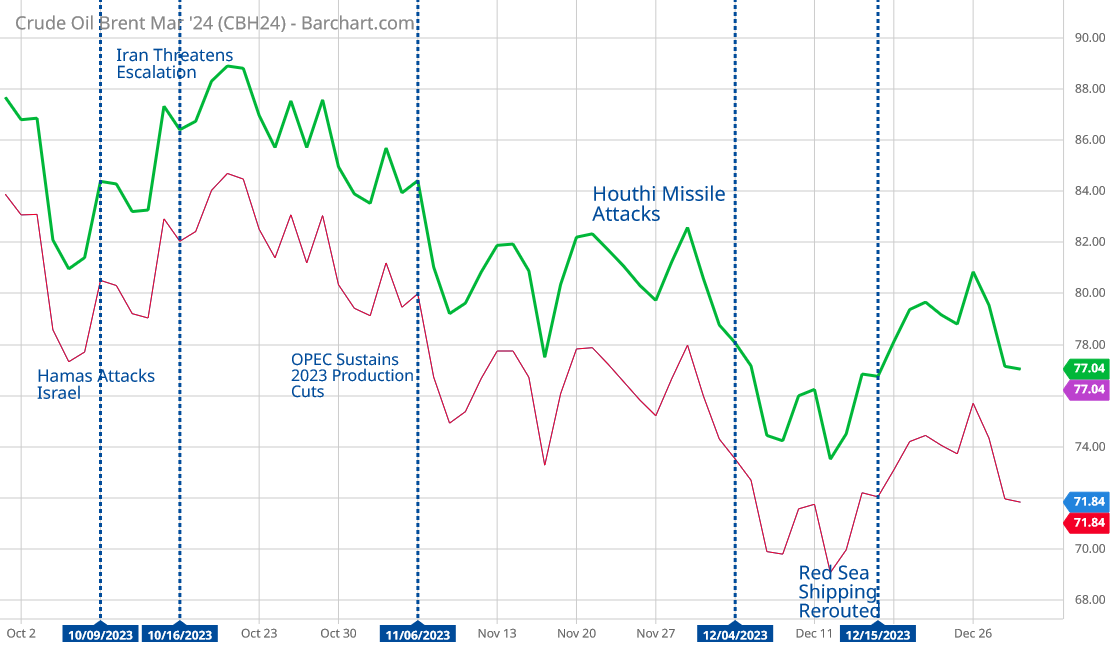

Despite the ongoing war between Israel and Hamas, oil prices (and therefore energy prices) have continued to fall, even as groups such as the Houthi rebels in Yemen continue to try to widen that conflict.

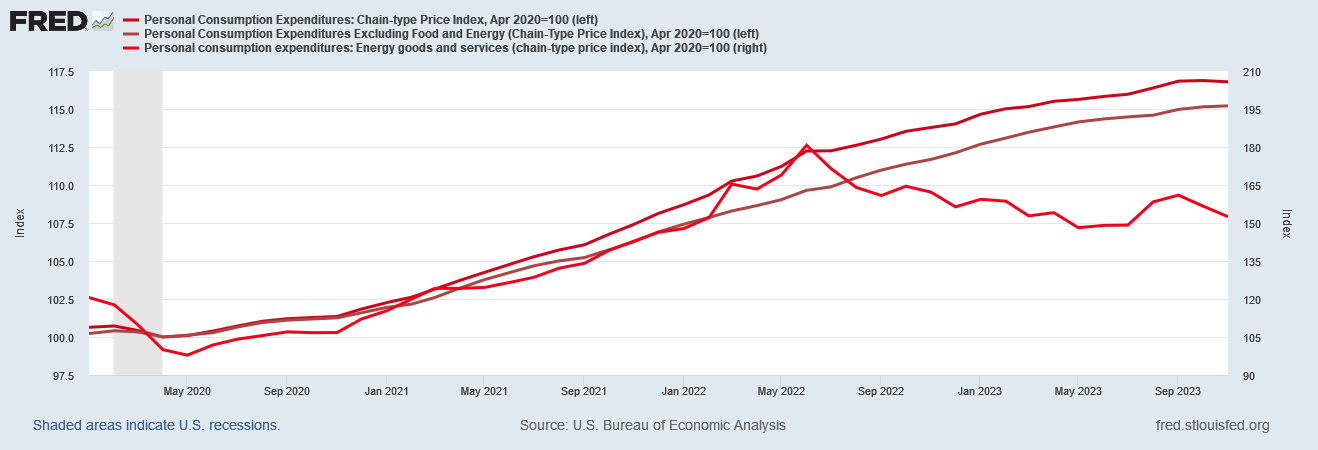

Yet despite the energy price declines, the reality of consumer prices after the Pandemic Panic Recession has been one of sharp and lasting increases.

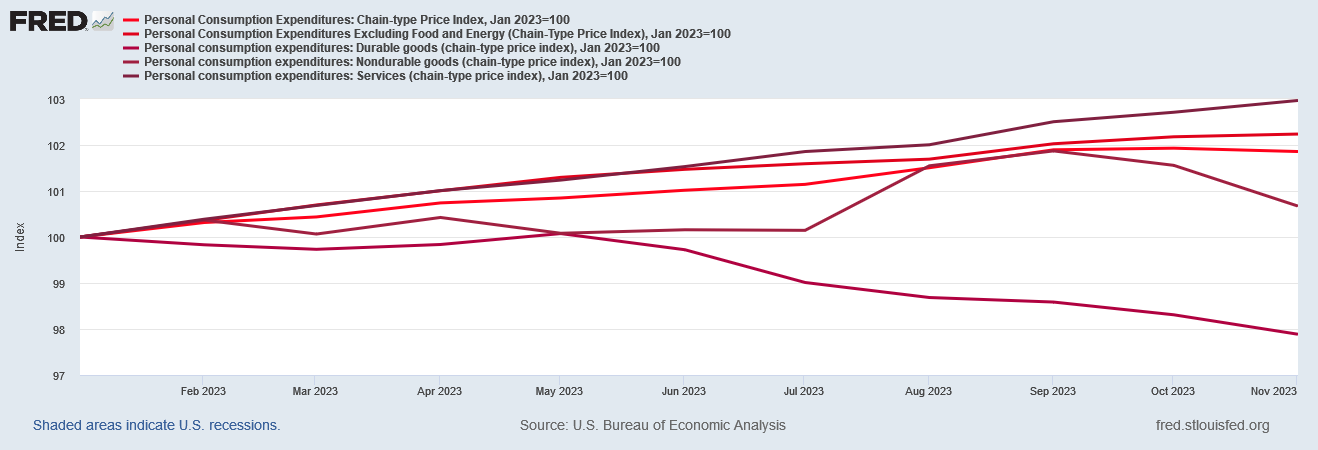

Nor should we overlook the growing price distortions being imposed on consumers by inflation. While durable goods have been in deflation for a while, and non-durable goods are now following suit, service price inflation has not ameliorated at all.

Against this backdrop of goods price deflation and service price inflation, that factory gate prices are reversing from inflation to deflation over the past two months merely reinforces the reality that the US economy is heading deeper into a deflationary or at best stagflationary recession. Bear in mind that this would be after the US has been enduring a “rolling recession” since some time in 2022.

If a deepening recession (depression?) is the reason yields are falling then we are all in a world of trouble!

While the media swoons over the prospect of a “soft landing” for the US economy and the Federal Reserve congratulates itself for having executed “immaculate disinflation”, the reality of the Fed’s own economic projections is that even the Fed believes this year will be a year of (deeper) recession. When GDP growth is expected to fall by 50%, “recession” is the only label that fits.

Yet even if the Fed’s own projections are only somewhat accurate, Wall Street’s haste in bidding down interest rates puts the Fed in a bind for the coming year. Having staked themselves to a position that the economy is going to slow significantly, the more data accumulates that the economy is continuing to slow and ultimately contract, the greater the pressure will be on the Fed to cut the federal funds rate and otherwise push yields down—down farther than Wall Street will have already bid them down.

Wall Street wants lower yields today, and is getting them. The lower the market yields are today, the more dramatic the Fed’s future actions will have to be in order to generate any significant monetary stimulus effect—and monetary stimulus is why a central bank pushes yields lower.

While the Fed notionally wishes to avoid a return to zero interest rate policies, a stagflationary recession while create considerable pressure on the Fed to reverse its balance sheet reduction strategy and begin buying Treasuries again. It will have to reverse the money supply contraction it has been pursuing since 2022—and that may very well reignite consumer price inflation once more (much would depend on how much of an increase in money velocity we see over the coming months).

Wall Street, of course, will be ecstatic if the Fed restarts the magic money printing press, as money creation has been a driving force in financial markets since 2008. Wall Street would like nothing better than a return to quantitative easing and cheap, easy, money, consumer price inflation be damned.

The question now is can Jay Powell find the policy chops to avoid rewarding Wall Street cynicism, and avoid giving Wall Street the cheap/free money it craves.

Amazing that the laws of supply and demand will still work with or without the Fed! Lol!

Something that puzzles me: you have said, today and previously, that yield “inversions have historically been taken as recession warnings”. Most of the Wall Street top dogs must surely be aware of this historic recession warning, yet they apparently no longer worry about such things. Is it a quick-buck mentality, that says rake in the dough today and worry about recession a few months from now, or is there a better explanation?