According to the International Energy Agency’s June Oil Report1, global oil demand will peak in 2028 at around 105.7 million barrels per day (mbpd). In their May Oil Market Report2, the IEA projected 2023 global oil demand at 102 mbpd. Presumably, the global demand for oil will be driven by growing demand in Asia, particularly India and China.

Expansion in global oil demand will be powered by faster-growing economies in the developing world, especially Asia, the report said. Around three-quarters of the increase in the six-year period to 2028 will come from Asia, with India surpassing China as the main source of growth by 2027. Meanwhile, oil demand in North America and Europe, where energy transition policies and efficiency gains will be most pronounced, will be in “contractionary mode” for most of the period, the report said.

Yet when we consider the ongoing slump in global oil prices, the question naturally arises: “is this forecast accurate”? If we look at the price and production data, it quite possibly is being too generous by a significant margin.

The first data point to consider is the ongoing slump in global oil prices. Both Brent Crude and West Texas Intermediate, two major global oil price benchmarks, have been trending steadily lower since this time last year.

Perhaps the most significant aspect about the steady decline in oil prices is that, of the signature events that nominally would provide support for oil prices, only Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has proven to provide any notion of sustainable price support for oil. China ending Zero COVID restrictions as well as both the OPEC and Saudi Arabia oil production cuts have failed to provide any but the most transient of price support for oil.

This sluggishness is causing oil market analysts to express more than a few doubts about demand growth forecasts.

Oil prices fell more than a dollar a barrel on Friday to record a second straight weekly decline, as disappointing Chinese data added to doubts about demand growth after Saudi Arabia's weekend decision to cut output.

However, given the breadth of the oil price slump world wide, we should perhaps be thinking in terms of declining rather than growing oil demand.

In addition to the slumping Brent and WTI benchmark oil prices, the price for the OPEC basket blend has been on the decline for over a year.

Both Russia’s ESPO and Urals blends have likewise been in decline, a trend that has only been exacerbated by sanctions arising from Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Even after Russian crude arguably burst through the G7 price cap earlier this year, the prices on Russian crude have continues to spiral down.

These just are not trends that are compatible with growing oil demand. They are trends that are compatible with shrinking oil demand.

Even oil bulls such as Goldman Sachs are taking a dim view of future oil demand, with Goldman Sachs recently trimming its oil price forecast to $86/bbl, a rather steep climb-down from its earlier $100/bbl+ forecasts.

Extra supply of around 800,000 barrels a day, mostly from sanctioned countries Russia, Iran and Venezuela, is behind the “bulk of the softening” in its price forecasts, the bank’s commodities analysts said in a research note Sunday.

“Russian supply has nearly fully recovered despite the decision by many companies to stop buying Russian barrels, and [effectively] a ban of Western financial and logistical services,” the bank wrote. Western firms can work with Russian producers only if they respect the price caps imposed on the country’s oil by Group of Seven countries.

Since late May, prices for Brent and WTI have fallen 6.8% and 7.6% to $73 and $69 a barrel respectively as disappointing economic data from China has dampened the global demand outlook.

On Wednesday, JPMorgan analysts joined Goldman Sachs in lowering their expectations for oil, projecting Brent Crude rising to just $81/bbl.

The Wall Street investment bank lowered its average 2023 forecast for Brent to $81 a barrel from $90 previously, and lowered its forecast for WTI to $76 a barrel for the same year from $84 per barrel.

Not only that, but the bank lowered its average 2024 forecast for Brent to $83 a barrel from $98 a barrel previously, and lowered its WTI forecast for the same year to $79 a barrel from $94 per barrel.

These trimmed forecasts come in the wake of Saudi Arabia’s latest production cut announcement, meaning the projections factor in reduced global supply and still come up with softer oil prices.

That is a pricing scenario that practically screams “shrinking demand.”

Yet it is not merely the price of oil that cast doubt on how much physical demand for oil is growing. Even within the US economy there are signs of flagging demand for energy products overall.

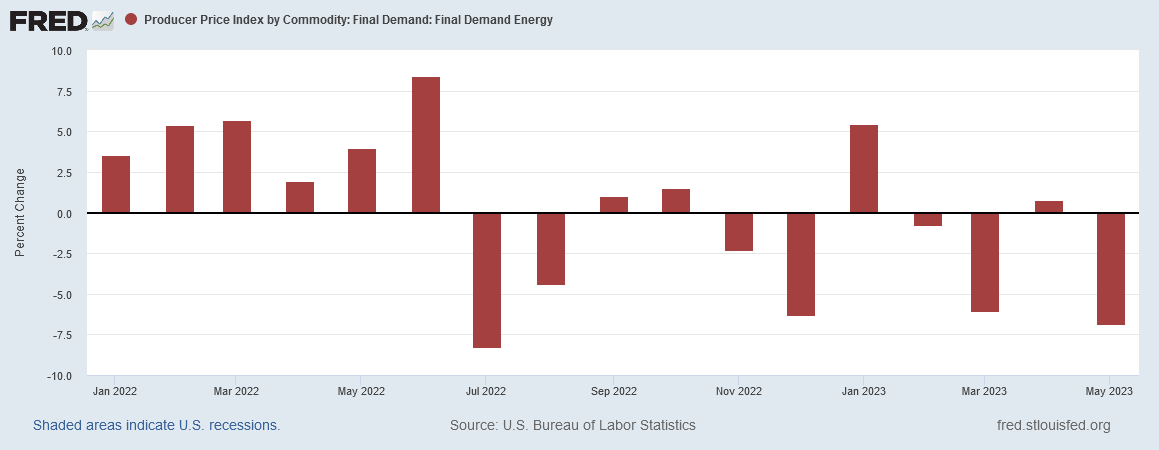

Energy producer prices have been showing deflation since last June.

Drilling into the energy PPI data, we see that the deflation is across the board, including among exported energy products.

Energy producer price deflation is occurring throughout the US supply chain, with declines showing up in both processed and unprocessed fuels.

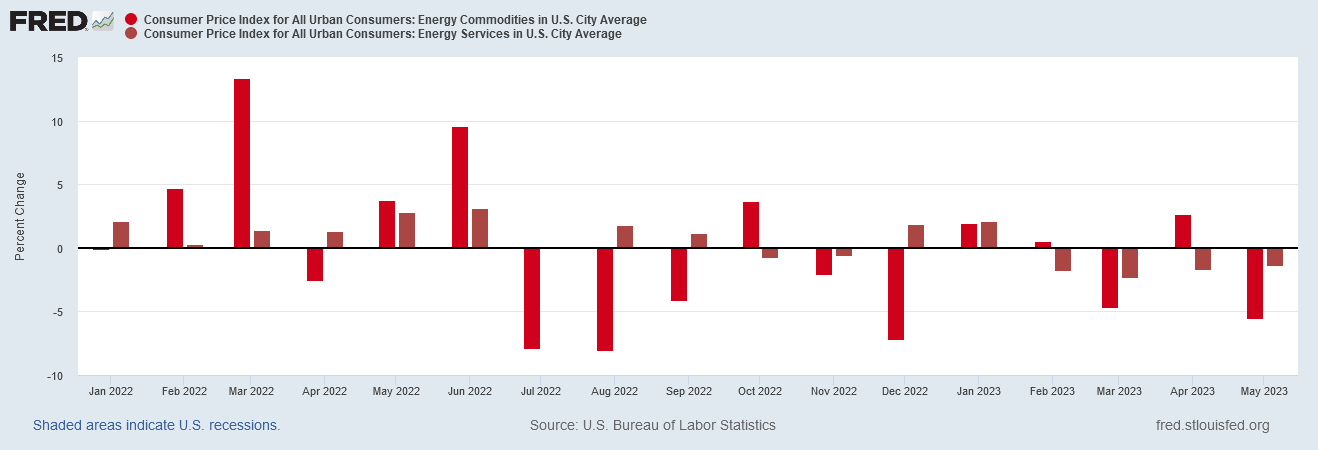

At the consumer price level, energy is also in deflation across the board, and have been since last June, in both the CPI and PCEPI data sets.

None of these are trends that speak to rising oil demand. All of these are trends that indicate declining oil demand.

Nor are the trends contained to just the United States. If we look at the world’s number two economy, China, we see again signs of shrinking oil demand.

Perhaps the most obvious sign is the steep drop off in China’s own domestic crude oil production.

After a surge in oil output in March, April’s production retreated to levels on par with October of last year.

While China is not a major oil producer it is a major oil consumer. If its own native production is tailing off that much that hardly is an optimistic gauge of China’s oil demand.

Additionally, China’s output of refined products has declined in recent months. Diesel fuel—one of the most common refined oil products—has tapered off from a peak last December.

If China is producing less diesel, by definition it is consuming less crude oil.

Moreover, China’s overall import levels have also sagged. A brief March surge quickly passed and import levels retreated to the same levels as last fall.

China actually had higher import levels while still under Zero COVID. If China’s import levels continue dropping, it is almost certain that at least some of that decline will be in China’s oil imports.

We can see signs of shrinking oil demand in China on the output side as well. Synthetic rubber production gives us one gauge of oil demand, as it is made from petroleum byproducts such as isopropene. While synthetic rubber production spiked in December, it has since retreated to its lowest level in six months.

With faltering outputs of products that use oil and oil products as inputs, it is not a difficult extrapolation to conclude that the demand for those inputs is also faltering. Certainly less oil and oil products are going towards rubber production, and in an environment of falling oil prices that can only suggest lack of demand.

While the analysts at Goldman especially view the declining oil prices in terms of excess supply—of major oil producers simply producing too much oil—that the softness in oil prices prevails even after OPEC as well as Saudi Arabia and Russia have sought to trim that supply is a strong indication that demand is faltering. For production to decline and oil prices to decline, oil demand must likewise be declining.

Even if sagging oil prices are a consequence of too much supply relative to demand, we still come to the same point where there is more oil for sale than there is interest in buying it at any price. For oil supply to continue to outpace oil demand even after significant production cuts, oil demand must be falling as well.

If these trends are indicative of sagging oil demand, and we are looking at a global trend of oil price deflation, then all forecasts of rising oil prices are automatically well wide of the mark. That in turn means that global economic growth forecasts are similarly wide of the mark. Oil price deflation today has to be taken as a strong indicator of broader producer and consumer price deflation tomorrow.

With central banks and government economic “experts” all viewing the state of the global economy as one of merely slowing growth, rather than outright contraction and deflation, the natural question is, given the totality of the data, how wide of the mark are they?

It is difficult not to see sagging global oil prices as a sign of impending global economic contraction, which shrinking prices leading directly to shrinking physical output. We’re already seeing shrinking physical oil production in several OPEC countries besides Saudi Arabia. We may already be at that point of global economic contraction.

There is no scenario where sagging oil prices speak to a rising economy. Sagging oil prices are what we have had for more than a year at this point, which means we are very likely looking at a sagging global economy as well.

Is deflation already here? In light of extended downward trends in oil prices, the answer may very well be “Yes”.

IEA (2023), Oil 2023, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/oil-2023, License: CC BY 4.0

IEA (2023), Oil Market Report - May 2023, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/oil-market-report-may-2023

You’ve got the data, Mr. Kust - irrefutable stuff!

Interestingly enough, others are starting to predict more stagflation and hard times, but you saw it all first. Seems like every day I see a headline in the Wall St Journal proving you right. And if you go to Peter Navarro’s latest Substack post, he is also predicting more stagflation.

(I’m not actually all that wild about Trump, but I read Navarro’s Substack to counter the daily disinformation that the MSM spouts. We have to piece it together by ourselves, right?)