JPMorgan Buys First Republic. The End Of The Bank Crisis?

Or Just The End Of The Beginning?

This morning the financial world was greeted with the much anticipated news that JP Morgan Chase had (finally) acquired First Republic Bank, at last putting the latter out of its deposit-deprived misery.

Essentially, Wall Street won this round of nuclear chicken with the FDIC, as both had been waiting for the other to make their move towards ending the First Republic Bank debacle. The FDIC took the bank into receivership, then turned around and sold it to JP Morgan Chase.

Regulators have taken possession of First Republic Bank (NYSE:FRC), resulting in the third failure of an American regional bank since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (OTC:SIVBQ) and Signature Bank (OTC:SBNY) in March. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has been appointed as receiver and accepted a bid from JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM) to assume all deposits, including all uninsured deposits, and substantially all assets of First Republic Bank. That includes $173B in loans and about $30B of securities, though it will not assume First Republic's corporate debt or preferred stock.

Thus ends this latest bank crisis soap opera. Or does it?

A key point to understand about this transaction is that JPM did not buy First Republic Bank outright. Jamie Dimon merely cherry-picked those parts of the carcass he deemed most tasty, and left the FDIC hyenas to deal with the offal. Per the FDIC press release:

As of April 13, 2023, First Republic Bank had approximately $229.1 billion in total assets and $103.9 billion in total deposits. In addition to assuming all of the deposits, JPMorgan Chase Bank, National Association, agreed to purchase substantially all of First Republic Bank’s assets.

First Republic’s common stock, preferred stock, and liabilities outside of its remaining deposits were all left behind.

Aside from First Republic’s deposits, what JPM did purchase included the securities portfolio which declining value was a principal source of First Republic’s misery. Given that Jamie Dimon and company cherry-picked the assets they wanted, JPM’s acquisition fundamentally confirms what I maintained last month at the time of First Republic’s Big Bank bailout: the securities are notionally healthy just low yielding relative to current treasury yields.

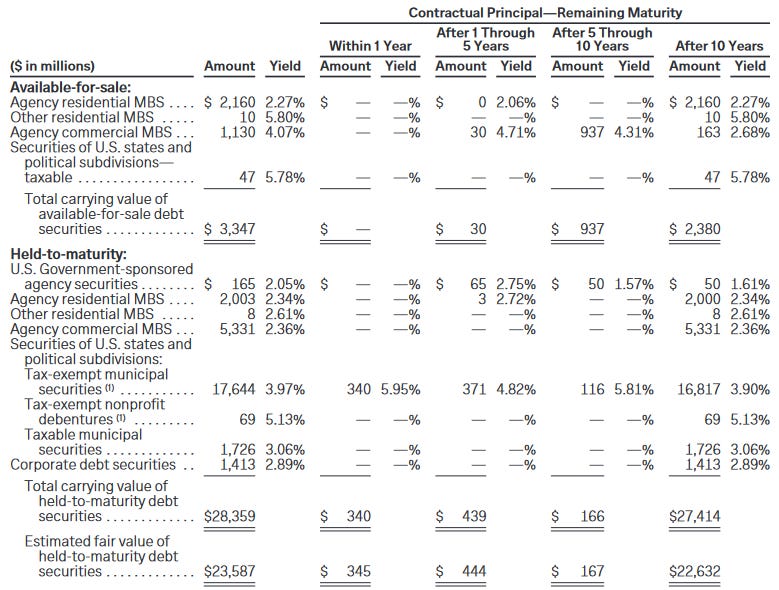

When we look at First Republic’s 10-K filing, for its breakdown of its debt securities portfolios, we see assets that are notionally healthy, but low yielding.

Some of the portfolios even have yields in excess of current market interest rates, and thus provide at least some unrealized gains.

First Republic was a fundamentally solvent bank brought to ruin by a bank run. The manner by which JPM acquired the bank’s assets proves that.

As I pointed out the other day, this bank run is the result of systemic issues which are steadily draining liquidity (and deposits) out of America’s banks—and out of America’s large banks in particular.

Why is the bank run happening? Because interest rates have risen and are anticipated to keep rising. This shift in the financial environment is causing large banks in particular to lose deposits across the board.

Among domestic banks, the 25 largest banks—what the Federal Reserve terms “large domestically chartered commercial banks—had as of March 1 lost 5.5% of their January 2022 deposit balances. All other domestically chartered commercial banks held 0.5% more of their January 2022 deposit balances as of that same date.

Large banks are bleeding deposits primarily because bank deposits are no longer providing enough yield for wealthy customers in particular to justify keeping their deposits there—not when money market funds are offering interest rates more in line with current treasury yields, as a quick survey of money funds offered by Charles Schwab Asset Management confirms.

Schwab’s money market fund yields are right in line with the yields on 1-Year and 2-Year Treasuries.

UBS offers money market funds with similar yields.

Yields such as these are a primary reason large banks in particular have lost over 6% of their deposits since January, 2022.

The national average interest rates on various deposits offered by banks are but a fraction of what large depositors can earn in money markets.

For the wealthy depositor looking for a good place to park excess cash, bank accounts just don’t make sense in the current rising interest rate environment.

Nor is there much doubt that deposit funds have been flowing from banks into money market funds. From January, 2022, through March, 2023, domestic banks have lost some $518 Billion in deposits, while money market funds have gained over $570 Billion. Charting the flows over time shows the flow pattern unequivocally.

One point deserves extra emphasis: this outflow has been a crisis of large banks up until the Silicon Valley Bank collapse in March.

Absent the panic attacks caused by regulators seizing banks, small institutions were more than holding their own where deposits were concerned. The deposit flight has been up until the past two months entirely confined to the 25 largest banks as classified by the Federal Reserve1.

How do money market funds manage to keep their deposit interest rates in line with market yields on Treasuries? In part because money market funds do not, as a rule, hold securities for any great length of time, but churn them through financial markets, thus constantly keeping abreast of current yields—the very thing that banks have not done.

Perversely, the greatest facilitator of this sort of market activity (which, just to be clear, is 100% legitimate) is none other than the Federal Reserve itself. One of its less-discussed liquidity tools is the Reverse Repurchase (“reverse repo”, for short) facility.

Reverse Repurchase Agreements are when there is a sale of securities with an agreement to repurchase them at a future date for a higher price2.

The Federal Reserve has been offering reverse repos since late 2002, and greatly expanded the facility in 2014, only to see it take off after the 2020 government-ordered recession.

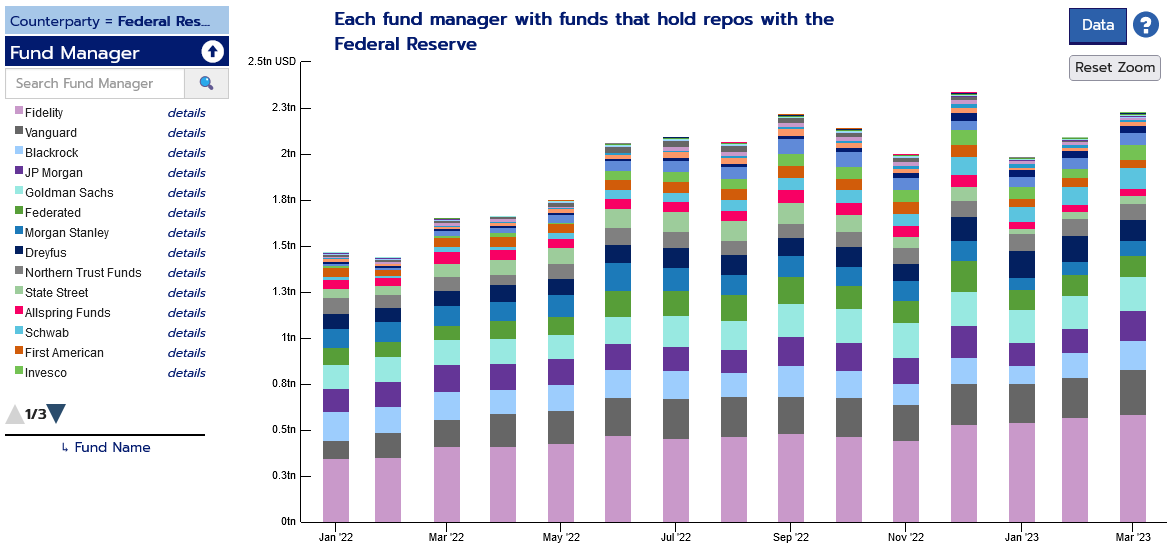

As the Federal Reserve has hiked the federal funds rate, money market funds have parked increasing amounts of cash in the Fed’s reverse repo facility.

Moreover, money market funds are by far the major participant in the reverse repo facility.

Not only has the Fed played a part in pushing interest rates up, it has been the primary means by which deposits have been drained from the large banks.

One would think that the Federal Reserve could simply shut down the reverse repo facility, or at least make it less attractive for parking cash, which in theory would reverse the fund flows.

There is a catch, however.

Bank deposits are a primary component of the money supply. Reverse repo funds are not. Thus, as the Fed tries to remove what it thinks is “excess liquidity” from the system—too many unattached dollars—it drains deposits from the system.

Perversely, this turns out to be yet another indicator that the Fed’s rate hike strategy is wrong-footed, because even though the strategy is meant to emulate that used by Paul Volcker during the early ‘80s, when Volcker deployed his rate hikes neither bank deposits nor the money supply actually decreased.

However, because the prevailing wisdom is that there are too many dollars sloshing around the financial system, an objective of the Federal Reserve is to simply remove them.

If the reverse repo facility were abruptly terminated, it would dump ~$2.6 Trillion back into the money supply—the exact opposite of what the Fed wishes to accomplish.

Consequently, the Federal Reserve is going to sustain the reverse repo facility for the foreseeable future, as a means of keeping liquidity flowing out of the system rather than into it—in the increasingly vain hope that this will magically reduce inflation3.

For the same reasons, deposit outflows and thus shrinking liquidity among US banks is likely to remain the systemic phenomenon it has been all along.

With the systemic issues behind the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and now First Republic Bank ongoing, does this mean there will be more bank failures to come?

Certainly Jaime Dimon does not think there will be.

In speaking with Wall Street analysts Monday morning, JPMorgan Chase (NYSE:JPM) Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon said, "This part of the crisis is over," adding that JPM's acquisition of First Republic Bank (NYSE:FRC), will help stabilize the banking system. That refers to the deposit withdrawals at U.S. regional banks.

Analysts at Bank of America share that sentiment.

JPMorgan Chase's (NYSE:JPM) acquisition of First Republic Bank (NYSE:FRC) "should likely end forced sales of banks due to deposit flight," said Bank of America Securities analyst Ebraham Poonawala in a note to clients on Monday.

As readers are already aware, I do not.

First Republic Bank is the latest banking domino to be knocked over by bank regulators and the Federal Reserve. First Republic Bank will not be the last such banking domino. The Federal Reserve and the FDIC’s regulators are sure to see to that.

For that matter neither does much of Wall Street. In fact, we are already getting a preview of the two likely next banks to tumble: PacWest Bancorp and Western Alliance Bank. Both banks dropped dramatically in the wake of First Republic’s acquisition by JPM.

Even JPM dropped 0.46% of its share price on the day’s trading, while fellow large institutions PNC Bank and Bank of America lost 2% and 1.49% on the day, Wells Fargo inched down 0.37%, and the broader S&P 500 Financials Index shed 0.27% of value.

Clearly Wall Street does not share Dimon’s confidence that the crisis is over. For all the reasons stated above, they are right not to share that confidence. I certainly do not share that confidence.

What First Republic Bank shows is that the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank of New York in March were anything but a fluke. They were, and First Republic Bank is, symptoms of a growing liquidity crisis and structural disequilibrium within financial markets.

The crisis and the disequilibrium are the direct result of how the Fed has chosen to attack inflation—by persistently shooting at wrong targets and refusing to look at the totality of financial information to gauge the efficacy of its tactics. The Fed is showing no signs of changing its misguided and historically illiterate strategy, and that means the liquidity crisis and the structural disequilibrium will only get worse, until market and economic chaos force the Fed to change tactics.

Because the Fed is determined to out-stubborn inflation, we may be certain of this much: more bank failures are coming. We cannot be certain which bank will be next, but there are enough banks hemorrhaging deposits and share price that we can reasonably anticipate that at least one of them will find themselves facing FDIC receivership and a forced “shotgun” marriage with another, nominally “healthy” institution. With three such failures already in the history books, it will not take much for Wall Street to demand a systematic policy response to what is now demonstrably a systemic problem.

First Republic Bank’s takeover by JP Morgan is thus not the end of the crisis. It is not even the beginning of the end of the crisis. At best, the First Republic Bank takeover by JPM is the end of the beginning of the crisis.

The Federal Reserve defines “large domestically chartered banks” as “…the top 25 domestically chartered commercial banks, ranked by domestic assets as of the previous commercial bank Call Report to which the H.8 release data have been benchmarked.” All other domestically chartered banks are by definition considered “small domestically chartered banks”.

Chen, J., “What Is a Reverse Repurchase Agreement? How They Work, With Example”, Investopedia, January 6, 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/reverserepurchaseagreement.asp

For brevity’s sake, newer subscribers are encouraged to read my earlier articles where I challenge this assumption lurking behind the Fed’s rate hike strategy.

As usual, I salute your brilliant explanation of the problem.

Two questions: are the holders of the common stock, preferred stock, and other liabilities taking a complete loss, with no recourse? And did JPMorgan get a sweet enough deal to incentivize big banks to manipulate more of such deals?