There is a key aspect to interest rates that frequently goes unexamined: Interest rates are the cost of money.

Let that thought sink in. Rising interest rates mean the cost of money is going up—higher interest rates make money more expensive.

This characteristic of interest rates is why rising interest rates give investment funds considerable grief: They raise the cost of covering investments when the markets move in unanticipated directions. For this reason, it is common practice for investment funds to keep a portion of the overall fund portfolio in cash, in order to meet various payment obligations, including margin calls.

When funds don’t have enough cash, they can find themselves forced to sell off their assets at inopportune moments.

If a pension fund doesn’t have enough cash on hand, not only is the value of its portfolio imperiled, but its ability to make required payments to pensioners can quickly be thrown into doubt.

There is a growing indication that US pension plans—which are some of the largest and most influential investment funds on Wall Street today—might not have enough cash to navigate a financial environment marked by rising interest rates.

Cash holdings are the lowest since the financial crisis at U.S. government pension funds and just above last year’s 13-year low for U.S. corporate pensions, heading into a year that many on Wall Street expect to test investors.

Cash holdings hit 1.9% of assets at state and local government pension funds and 1.7% of assets at corporate pension funds as of June 30, according to an annual snapshot from Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service

That’s a problem.

The US got an early preview of what can happen when pension plans don’t have enough cash on hand at the end of September, when rising interest rates triggered a cascading series of margin calls for UK pension plans, leading to forced liquidiation of plan assets at fire sale prices.

The Bank of England felt compelled to intervene in the markets to restrain the rise in debt yields (interest rates on debt), thereby stopping the pension plan margin calls.

Declining cash on hand percentages among US pension plans mean a rising probability that a similar liquidity crisis could very well be brewing on this side of the pond as interest rates move higher.

On the one hand, maintaining the “right” amount of cash on hand is part of the challenge of pension plan management—holding too much cash reduces investment returns, but holding too little leads to liquidity problems. On the other hand, however, pension plan managers have for years moved money into riskier and less liquid investments.

During a decade of low rates, pension managers searching for high returns pushed into illiquid private markets. They also invested money through the use of derivatives, contracts whose value is linked to or derived from another asset, in an effort to gain exposure to high-quality bonds without tying up much money in the low-yielding asset class. Appreciating stock and bond portfolios provided an easy source of cash.

Chasing returns at the expense of liquidity has left many pension plans exposed to potential liquidity problems now that interest rates have increased.

And pensions have been chasing returns at the expense of liquidity, taking on more and more risk hoping not to get caught crossways of a bad investment.

So-called “alternative” investments now comprise 24% of public pension fund portfolios, according to the most recent data from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research. That is up from 8% in 2001. During that time, the amount invested in more traditional stocks and bonds dropped to 71% from 89%. At Mr. Majeed’s fund, alternatives were 32% of his portfolio at the end of July, compared with 13% in fiscal 2001.

Unfortunately for pensions, the returns have not always been there. Two of the largest public pension plans, the California Public Employees Retirement System and the California State Teachers Retirement System, posted investment losses in their most recent fiscal year.

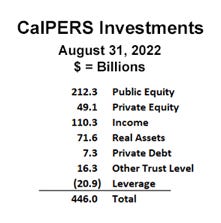

The California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, the nation’s largest state pension fund, experienced a 6.1% investment loss in the fiscal year that ended June 30. It was the first annual loss since the Great Recession for the fund that provides pension benefits to employees of the state and nearly 2,900 counties, cities, special districts and other public employers. Assets fell to $440 billion after topping $500 billion last year.

The California State Teachers’ Retirement System, or CalSTRS, the nation’s largest teachers’ pension plan, lost 1.3% last fiscal year, its first decline too in more than a decade.

Although CalPERS does not have the percentage of derivative and other high-risk illiquid assets among its asset allocations that some plans have, it has still indulged in at least some highly speculative investments while generating that investment loss.

And then there is “Other Trust Level” investments, where CalPERS has deigned to commit over $16 billion. In the footnotes to CalPERS Trust Level Quarterly Update, decipher this description: “Trust Level Financing reflects derivatives financing and repo borrowing in trust level Synthetic Cap Weighted and Synthetic Treasury portfolios.” Good luck with that. This is pre-financial crisis speculative behavior, the sort that almost brought down the entire financial system. To further put this in context, “Leverage” refers to money CalPERS borrowed in order to make additional investments, hoping those investments would earn more than they paid to borrow the money.

Nor are CalPERS and CalSTRS alone. The majority of public pension plans lost money over their most recent fiscal year. Again and again, fund managers have in 2022 been caught short by a shifting investment climate.

Nor is the investment situation for public pension plans at least likely to improve, as almost all public pension plans are significantly underfunded. With politicians loathe to tackle this issue directly, plan managers are left with the awkward challenge of making up as much of the funding shortfall as they can through their investment prowess.

As Quoth The Raven noted on his “Fringe Finance” Substack back in September, the failure of pension plan managers to measure up to that challenge sets the stage for a very rocky 2023 for more than a few pension plans.

The fact that these funds were unable to post the returns that they needed during arguably the most euphoric bull market in history is extremely concerning. When conditions get worse for poor managers like these, like they are now, the capital destruction could be devastating.

With pension plans poised to lose even more money in 2023, and with even the investing behemonth CalPERS making forays into the same derivative investments that triggered the September market meltdown among UK pension plans back in September, the declining amount of cash on hand to cover little inconveniences such as margin calls could quite easily put the Fed in the same position the Bank of England was then. Should the same cascading margin call scenario unfold here in the US, the Federal Reserve will quickly find itself having to choose between maintaining its tighter monetary policy and preserving the assets of the nation’s pension plans.

Already, the White House has seen fit to bail out one of the largest Teamsters’ pension plans, the Central States Pension Fund, to the tune of $36 billion.

Many union retirement plans have been under financial pressure because of underfunding and other issues. Without the federal assistance, Teamster members could have seen their benefits reduced by an average of 60% starting within a couple of years.

How many more pension plans will need government assistance over the coming months?

While Jay Powell has shown surprising commitment to the Fed’s inflation-fighting strategy, should there be a general market meltdown among pension plans similar to what happened in the UK, it will be almost impossible for the Fed to avoid making the “pivot” back to low interest rates and a more generous monetary policy. The political pressures that are sure to arise from the specter of the nation’s retirees losing some or all of their pension benefits practically guarantee that outcome.

That pension plans might not be holding enough cash to navigate whatever investment ups and downs 2023 might bring is not, by itself, a sure sign of an imminent meltdown. It is, however, a sign that pension plans are, in general, vulnerable to sudden market reverses, in an investment climate where sudden market reverses are increasingly likely to happen.

Similar to the signals represented by rising discount window usage and rising FHLB borrowings by the nation’s banks, a shrinking cash cushion signals structural weakness among the nation’s pension plans.

That shrinking cash cushion raises the probability that, as the Fed continues to push interest rates higher, at least some number of pension plans will find themselves having to suddenly liquidate assets to cover one or more investing positions undone by the rising rates.

The shrinking cash cushion is not itself a sign of a coming liquidity crisis. Rather, it is yet another sign that when the liquidity crisis does come, there will be significant and far-reaching contagion effects.

The shrinking cash cushion is a warning that, as the Fed pushes interest rates higher and makes money more expensive, pension plans are increasingly likely to be among those who will learn the painful lessons of just how expensive money can be.

" Interest rates are the cost of money."

Yes. And when something costs very little, what does that say about its value? ;)

Pension funds were in a world of hurt during and right after the GFC. The only thing that saved them was the re-inflation of the asset bubble, which got bigger (and thinner walled) that it has ever been. That asset bubble inflation was possible due to the artificially low interest rates that had been maintained ever since. It should have been obvious that this was unsustainable and would have to end at some point.