Persistent Inflation Is A Failure Of Government

Government Inexpediency Is The Leading Cause Of Inflation

Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient

Henry David Thoreau, “Civil Disobedience”

When we grapple with the challenges of inflation, monetary policy, and economic policy, either for this country or for any country, we somewhat reflexively look to the institutions of government to address any challenges and defects we percieve.

Is this the best approach? Is government really the way to address such problems?

Indeed, the inflationary (and stagflationary) challenges all nations are currently facing greatly call into question the capacity of governments to address such matters. Henry David Thoreau, in his landmark essay “Civil Disobedience”, characterized all governments as “inexpedient”1, and the current array of economic challenges certainly give credence to his depiction.

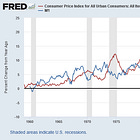

Yet it is not merely the current situation that calls into question the capacity of government to competently address inflation. Several times I have explored in this newsletter the serial failures of not just the US government (under the auspices of the notionally independent but highly co-opted Federal Reserve) but also Japan’s government via the Bank of Japan.

There have been many instances of inflation and monetary policy mismanagement by the Federal Reserve, but their response to the Pandemic Panic, the lockdown, and the ensuing recession is by far the worst such episode of sheer policy incompetence.

At the end of Part 1 I asked the question “What was the Fed thinking?”

As best I can determine, they weren’t. At all. In the 40 years since the Volcker rate hikes, the Fed has become so accustomed to fiddling and futzing with the money supply and interest rates that it became simply assumed that whatever policy objective they desired would be the outcome of whatever fiddling and futzing they did.

Suffice it to say, they were wrong. Now they’re caught between a monetary rock and an interest hard place—and so are we all.

Yet the Federal Reserve is hardly alone in this. Arguably, the entirety of Japan’s economic experiment known as “Abenomics” also qualifies as an egregious policy faux pas.

Abenomics thus highlights the reality that government policy is a poor substitute for healthy, free, and unfettered markets. Government policies can tank an economy, as the BoJ’s careless whiplash from loose to tight monetary policy did in the 1990s, but government policy cannot resurrect an economy once it has tanked.

Jerome Powell and his colleagues at the Federal Reserve would do well to remember this as they attempt to corral consumer price inflation in the US without tanking the US economy. Doing too much is a far more dangerous outcome than doing too little.

Perversely, Abenomics not only mostly failed to push through sustained inflation as a palliative to Japan’s serial lost decade, it has thus far been unable to rein in inflation now that the Pandemic Panic has unleashed truly inflationary forces globally.

What makes this failure seem even stranger is that Japan has some of the lowest yields on sovereign debt, and has persisted in this, even as inflation has soared higher than Japan has seen in a generation.

Japan’s debt yields are not merely low, with inflation factored in they are one of the few nations still tolerating negative real yields on sovereign debt—and the Bank of Japan has done nothing to push these rates up.

Paradoxically, Japan might be the one country that is theoretically doing monetary policy “right”, at least if we consider the assessments of the late Milton Friedman2, Nobel Laureate and one of the leading lights of monetarist economic theories.

Initially, higher monetary growth would reduce short-term interest rates even further. As the economy revives, however, interest rates would start to rise. That is the standard pattern and explains why it is so misleading to judge monetary policy by interest rates. Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy.

Certainly Japan challenges the idea that interest rate manipulations are the surest route to containing consumer price inflation. Despite holding interest rates within a narrow (and low) band, inflation has both risen and fallen for Japan in recent years.

With so little movement in Japanese interest rates, it is difficult if not impossible to assign any meaningful correlation between those interest rates and consumer price inflation—a correlation that even Milton Friedman denied existed.

After the U.S. experience during the Great Depression, and after inflation and rising interest rates in the 1970s and disinflation and falling interest rates in the 1980s, I thought the fallacy of identifying tight money with high interest rates and easy money with low interest rates was dead. Apparently, old fallacies never die.

Of course, as I have explored previously, even the prime mover of the strategy to manipulate to regulate inflation, Paul Volcker, did not accomplish quite the victory over inflation that history has accorded him.

Powell is heading down this wrong path because the Volcker myth is fundamentally wrong: Paul Volcker did not “beat” inflation with interest rates. He merely ring-fenced it, keeping it corraled but never ever fully tamed.

Indeed, the data shows that country after country has grappled with high consumer price inflation in the past couple of years, with at best problematic success. Inflation has risen—and fallen—largely in sync across most of the industrialized world.

Even China, where inflation is so low as to present the challenge of deflation, has seen its price indices move largely at the same time as other nations.

Yet country after country persists in using interest rates to attempt to control inflation. Russia recently boosted its key interest rate to 15%, even as inflation has continued to soar out of control.

The central bank has now raised rates by 750 basis points since July, including an unscheduled emergency hike in August as the rouble tumbled past 100 to the dollar and the Kremlin called for tighter monetary policy.

“Current inflationary pressures have significantly increased to a level above the Bank of Russia’s expectations,” the bank said in a statement, pointing to domestic demand outpacing the provision of goods and services, and high lending growth.

Earlier this year, both the European Central Bank and the Bank of England followed the Federal Reserve’s lead in raising interest rates, yet market yields stubbornly refused to follow suit at the time, and the central banks’ influence on inflation has been entirely problematic.

This pattern of central bank policy error and impotence is repeated quite literally around the world. The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan have all used disparate methods to address inflation and monetary policy within their respective countries, and in every instance the methods used have proven ineffective at bringing down inflation, and problematic in raising inflation in the case of pre-pandemic Japan.

The inability of governments and central banks to rein in rampant inflation over the past few years is made even more egregious because of one simple reality: these same governments indisputably caused the inflation with their insane (and ineffective) lockdown policies to combat COVID-19. Even at the time it was apparent that these policies would cause significant economic disruption and dislocation.

Subsequent research would confirm this to be true.

In 2020 no government asked one simple question: who counts the deaths from recession?

Governments did not stop to count the full cost of their deluded and dysfunctional policies. They merely blundered over the COVID cliff practically in lockstep, and the continued high inflation present around the world is but one highly visible consequence of that policy error.

Which brings us back to Henry David Thoreau’s observation about governments being inexpedient. Since the Pandemic Panic, there is little argument but that governments have been extremely inexpedient in controlling consumer price inflation. The very best that can be said is that governments have not made inflation worse, or at least not that much worse. In no case can it be persuasively stated that the central bank has succeeded in controlling inflation and keeping it down below levels where its economic damage is perceptible. The very worst that can be said is that governments are proving utterly unable to clean up their own messes.

Consumer price inflation descended upon the global economy because of government incompetence and economic illiteracy. Because of government incompetence and economic illiteracy consumer price inflation has persisted. No government has managed to “get it right”, not in 2020 and certainly not since.

Thoreau began “Civil Disobedience” with the proposition “That government is best which governs not at all.” Watching governments try and fail to undo the damaging inflation they have caused gives that proposition new life and new relevance.

This much is certain: but for government we would have no inflation.

Thoreau, H. D. Civil Disobedience. 1849, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Civil_Disobedience_(1946). Retrieved Online from WikiSource

Friedman, M. “Reviving Japan”, Hoover Digest. 30 Apr. 1998, https://www.hoover.org/research/reviving-japan.

Yet a balanced budget bill, that literally "balanced the budget" remains as far in the future as one can imagine. Time to replace the government is the only conclusion one can come to.

"but for government we would have no inflation."

Over the long term, I believe that is correct. What we would have is some oscillation between inflation and deflation due to private credit expansion and contraction, with the long term trend actually being mildly disinflationary because technology improves productivity and makes things less expensive in real terms.