In every inflation discussion, the place where the rubber always meets the road is a person’s paycheck. As prices rise, if wages do not rise in proportion, the individual’s purchasing power is effectively reduced.

In periods of rising and elevated inflation, such as the period we have been in and are in now, the great stressor on everyone is the extent to which their paycheck is shrinking. Small wonder, then, that reader PAULA ADAMS asked about real wages on my earlier discussion of rents and the impacts of shelter price inflation on overall consumer price inflation:

Can you please do an analysis of how real wages are not going up for most Americans thanks to inflation? The working class knows they are not “making more money” just because they got a $2 raise.

Paula succinctly states the situation with respect to workers and their wages: workers have been losing ground to inflation.

I perhaps should say workers are “still” losing ground to inflation, as the situation is only marginally improved from July, when I last touched on the subject.

The data has changed since then, so perhaps it is time to revisit the topic and assess where things stand.

We need to keep current on what the data says about real wages, because what the politicians say about real wages is equal parts hogwash and horse hockey—such as Dementia Joe’s typically lunatic tweet last month.

Dementia Joe’s handlers really should consult at least some of the “official” data before tweeting out such nonsense, because lower wages—at least lower real wages, which are what matter—is exactly what the Regime has been delivering for workers almost since Inauguration Day, 2021.

Even the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ own computation of median real wages shows workers’ paychecks have been effectively shrinking since the Pandemic Panic Recession.

Moreover, the decline in real median wages is fairly substantial—over 6% since April of 2020.

Did I mention that this was using the BLS’ calculation of real wages? Which means this is the polished up version of the real wages turd. It gets worse from here.

The BLS’ monthly Employment Situation Summary and Consumer Price Index Summary tend to paint a somewhat misleading view of real wage increases and decreases. This is because the common comparison metric is the percentage year on year change, which does show some wage gains in 2020 right after the recession and again in the past few months.

Even by this benchmark, however, wages were losing ground to inflation by April of 2021, and continued to lose ground to inflation until June of this year. Arguably, the percent year on year change in average weekly earnings for September is just under the percent year on year change for the CPI, which means real wage growth shifted negative in the most recent reporting period.

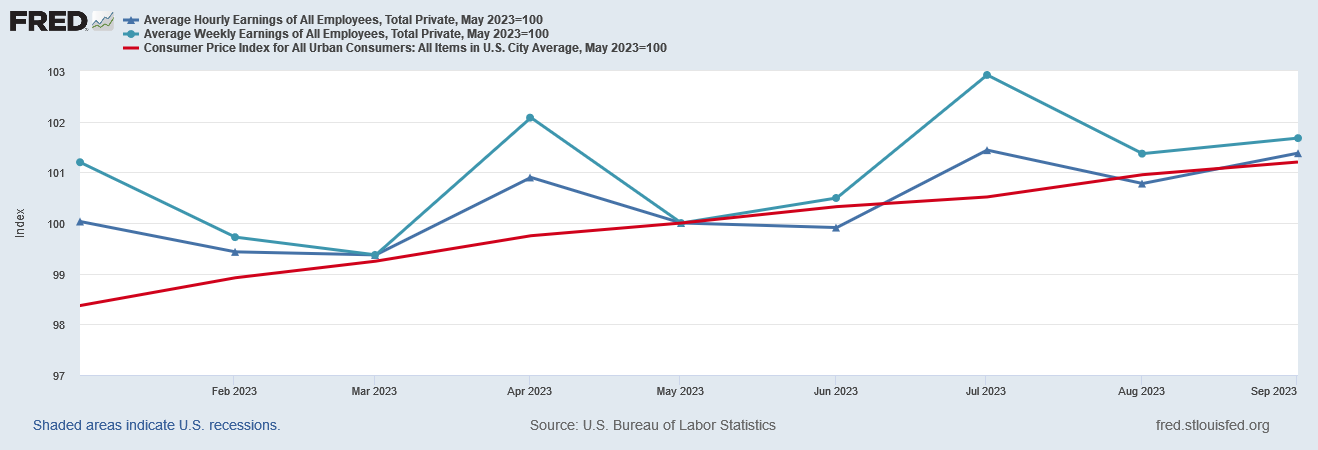

Yet the impact of the period of April 2021 through May 2023, when year on year inflation was running above year on year wage growth, has been to cumulatively cause incomes to lose major ground to inflation since early 2021. If we index wages and the CPI to the end of the Pandemic Panic Recession, we can see what has been happening with wages quite clearly.

Not only are workers’ wages losing ground to inflation, they are increasingly losing ground to inflation—things have been getting worse, not better.

How can that be, with wage growth above year on year inflation the past few months? Because indexing gives us a cumulative differential; it shows us how much more growth there has been in inflation vs growth in nominal wages. Thus the differential in cumulative growth since the 2020 recession between Average Weekly Earnings and Consumer Price Inflation was 6.1% in December, 2022, but has expanded to 7.1% by September 2023.

In other words, during 2023 to date, workers’ wages have lost a full percentage point of growth to inflation this year so far.

The only way that real wages can be shown to have increased is to index to June of this year, in the period where year on year inflation was less than year on year wage growth.

Shifting the index period forward just one month starts to muddle this picture, however.

If we index starting in April, right before the year on year differential turns positive, we don’t see any real wage growth at all.

Because the wage and inflation charts fluctuate monthly, whether the indexed data shows cumulative wage growth or not depends in part on which month is selected for the base month.

April of 2020 is a base month I use quite frequently, because that is the “official” end of the Pandemic Panic Recession. Theoretically, all influences from the recession have occurred, and what we should see going forward is post-recession growth and expansion. Alternatively, I also use the beginning a calendar year or a calendar quarter for the base period, as these are periods which align with various reporting schedules.

What the indexed data shows when we use these different base periods is that, since June of this year, real wages are finally gaining a little on inflation. Whether this will last is, of course, determined by wage and inflation growth going forward, and average weekly earnings’ growth year on year is already less than inflation year on year for September.

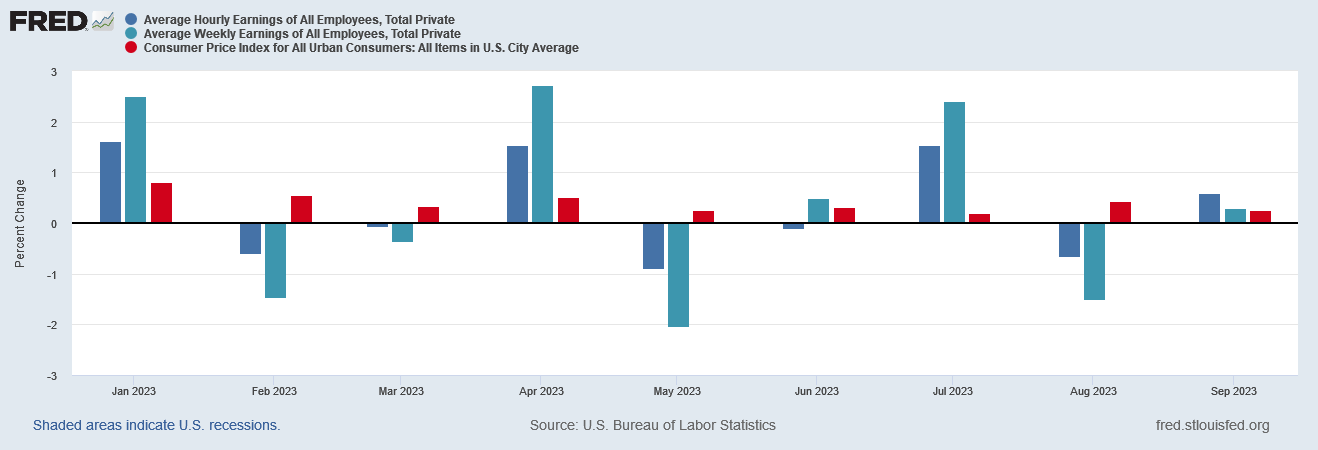

This is not to say that the wage picture is entirely bad. 2023 has been a somewhat better year for wages vs inflation than 2022. We can see that if we look at the month by month changes for wages and inflation from January of this year onward.

There have been some fairly good months this year for wages. We should not overlook that. Early 2023 certainly looks better than early 2022.

However, even at that, we are starting to see returning weakness in wages as of the September data. If inflation continues to tick upward for October, wage growth is very likely going to turn negative yet again.

Moreover, we should also realize that the CPI, when looking at the raw data, the optimistic view on inflation (the PCE Price Index is seasonally adjusted, thus preventing a proper apples-to-apples comparison here). The American Institute for Economic Research maintains an alternate consumer price inflation metric, the Everyday Price Index, which suggests that the cumulative effects of inflation are somewhat worse than what we see described by the CPI.

With prices having risen overall more under the EPI than under the CPI, it necessarily follows that real wages have shrunk more under the EPI than under the CPI. This is immediately obvious, as we see the same widening gap between the EPI index line and the average hourly earnings index line. For real wages to be increasing that gap has to be narrowing (when the average earnings index is lower than the inflation index), and only widening when the earnings index is greater than the inflation index. We don’t have the latter, obviously, so we are looking at inflation as measured by the EPI taking bigger bites out of worker paychecks than the CPI.

Which of these charts and metrics are “correct”? Which ones show what wages are “really” doing? Ultimately, they all do. As I have said more than once (and will almost certainly say again), “your mileage may vary.”

Everyone who has ever looked at the BLS’ monthly inflation report and said “there’s no way inflation is just X%”….you’re probably right. In your area, with your purchasing patterns, inflation’s impact is easily higher and sometimes lower than what is reported for the nation as a whole.

We do well to be mindful of these various and shifting contexts when we look any economic data, whether for a state, for the United States, or for the world as a whole. Not only is the rule “your mileage may vary”, it is almost mathematically certain that your mileage will vary.

What is true for inflation is also true for wages, and is therefore doubly true for real wages. The extent to which your earnings are increasing or decreasing is going to be unique based on your profession and your location, and even your overall buying habits.

However, what the broad data unequivocally shows is that, since the economy was derailed by the lunatic lockdowns and the Pandemic Panic Recession, real wages have been savaged by inflation. On a national basis, and over the longer span of time, inflation has gobbled up every penny of nominal wage increase and come back for seconds, thirds, and fourth helpings of purchasing power.

Do not let Dementia Joe or any other politician, or any corporate media “expert”, persuade you otherwise. The data shows workers’ wages have been declining, and while the past few months have seen some respite to the decline, the future does not bode well at all.

Enjoy your paycheck while you have it. Inflation may take it away sooner rather than later.

Thanks, Peter. I think wages are not increasing as fast in Texas for workers because we have an abundant supply of workers. In some states minimum wage is commonly $15/hr for jobs requiring no skills or experience, but in Texas there are still many jobs that pay $10 and still expect experience. You could say our cost of living is lower, but for renters and people who live paycheck to paycheck, it doesn't feel lower because they feel inflation more. Fast food prices and car insurance premium increases is really hurting working people.