Shelter Price Inflation May Be Starting To Cool. The Housing Crisis Is Just Getting Started

Peak Inflation Means The Damage Has Been Done. Now Comes The Fallout.

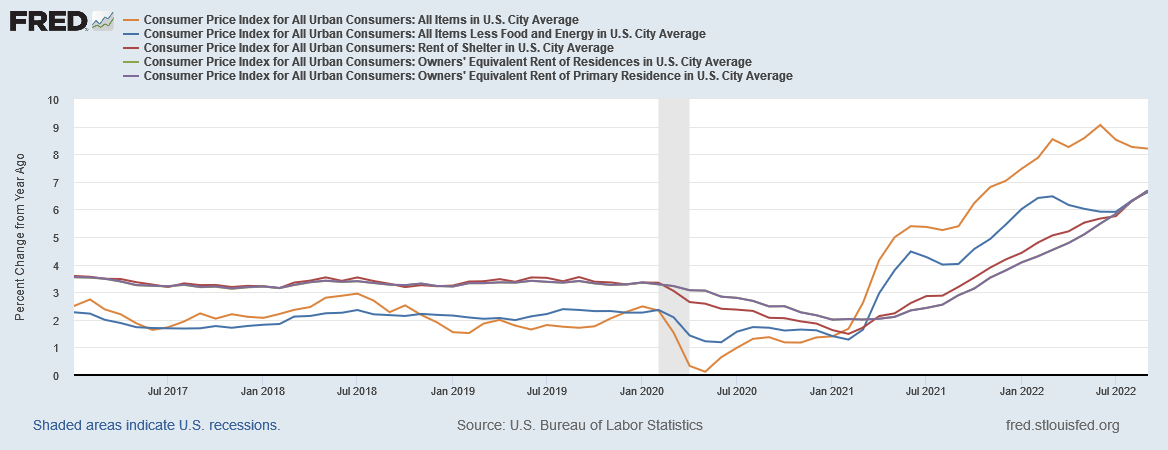

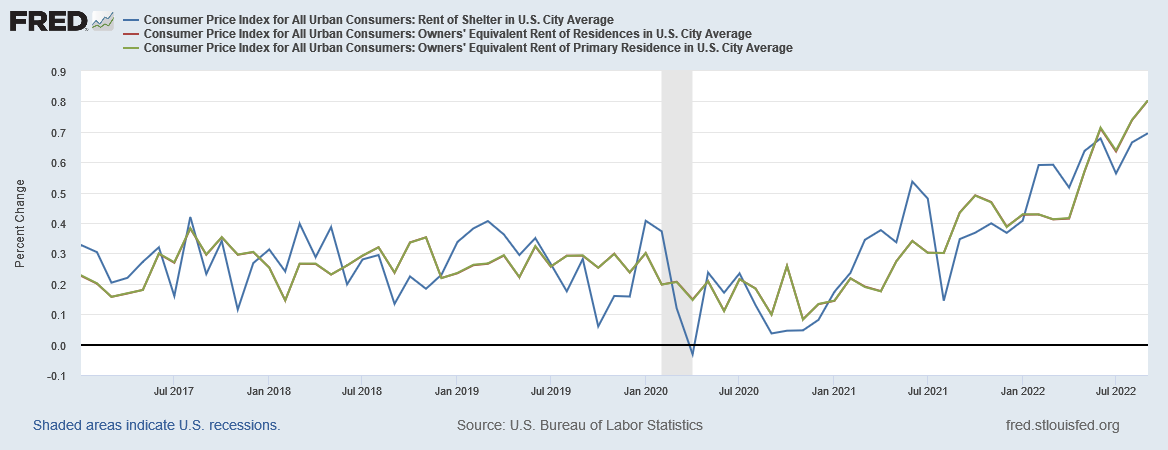

Buried in the details and tables of the September Consumer Price Index Summary report lies an uncomfortable truth: once again several of the metrics within the CPI that measure shelter price inflation have risen as fast as or faster than the “core” inflation metric into which they are amalgamated.

Increases in the shelter, food, and medical care indexes were the largest of many contributors to the monthly seasonally adjusted all items increase.

While the summary report narrative prefers to mention the seasonally adjusted data, the reality of shelter price inflation exists even in the raw data. The reality of the US economy is that it is becoming progressively more expensive to keep any kind of roof over one’s head. As consumer price inflation continues to climb in this country, shelter price inflation continues to be an outsized factor in that climb.

The Unspoken Crisis: Shelter Price Inflation Has Been High For Years

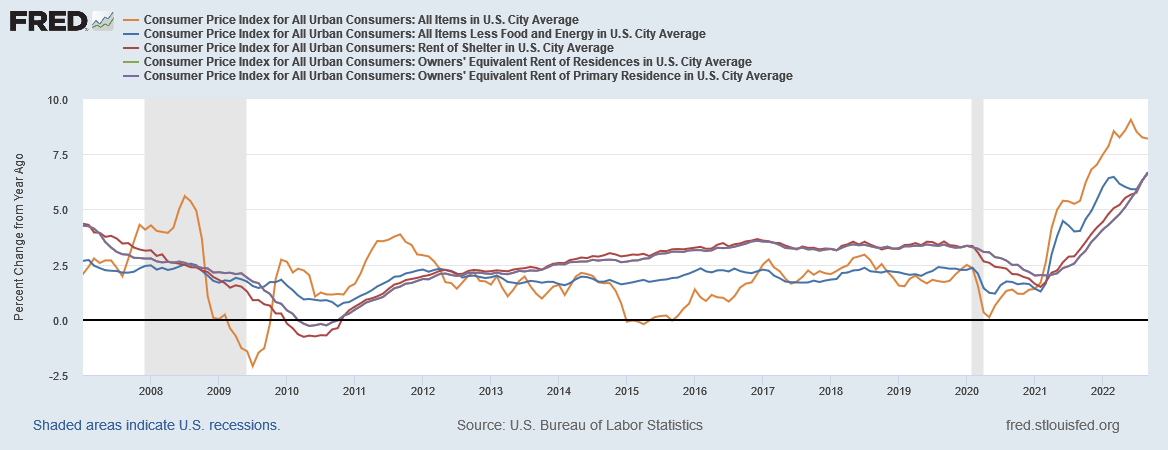

In one regard, we should not be surprised to discover that shelter price inflation is outpacing core inflation. When we look at shelter price inflation metrics within the CPI going back to 2007, we quickly see those metrics have outpaced both headline and core inflation since around September 2012.

Even the pandemic panic-induced 2020 recession did not push shelter price inflation below the headline rate—not until 2021 when the headline and core rates took off.

Yet the corporate media has by and large ignored shelter price inflation, and for the most part still does.

Nevertheless, shelter price inflation continues its post-2008 pattern of remaining stubbornly above headline inflation, which means that the cost of having a roof over one’s head will be a primary driver of core inflation in this country for at least some months yet.

It Began With Inflation In Housing Markets

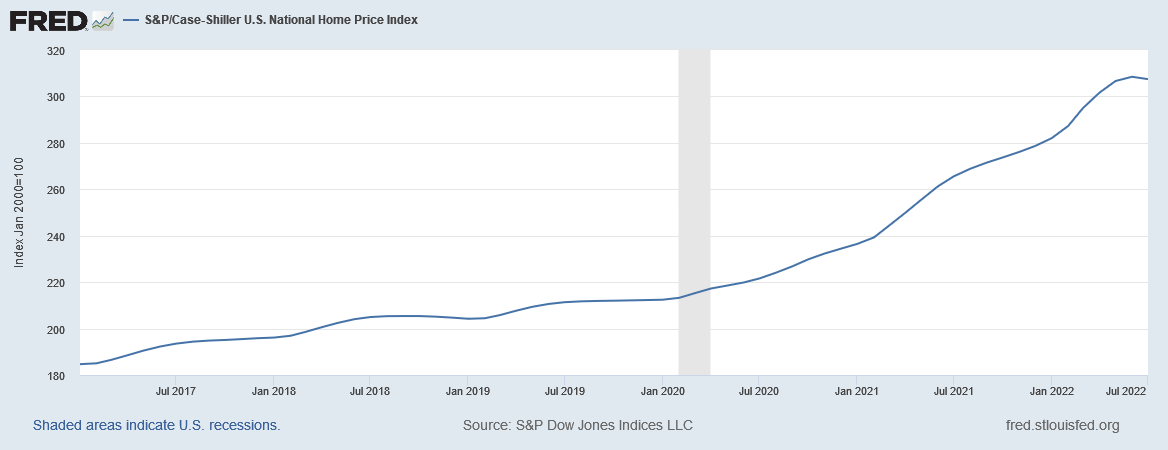

The steep rise in rents over the past year and a half in one regard is not difficult to understand. At least a part of its origin lies in the equally steep rise in the sale price of both new and existing homes, beginning in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic panic lockowns of 2020, and the ensuing recession1.

The vast majority of adults in the United States view renting as a stepping stone to homeownership. Therefore the availability of affordable homes in the for-sale market dictates how many compete for homes in the rental market. For-sale supply and affordability were both worsening in the years leading up to the pandemic, but conditions worsened rapidly in 2020 when new home construction slowed and wary sellers pulled off the market. In March 2021 there were fewer than 700,000 houses for sale across the country, a 48 percent drop in inventory compared to the year prior. In response, home prices have surged.

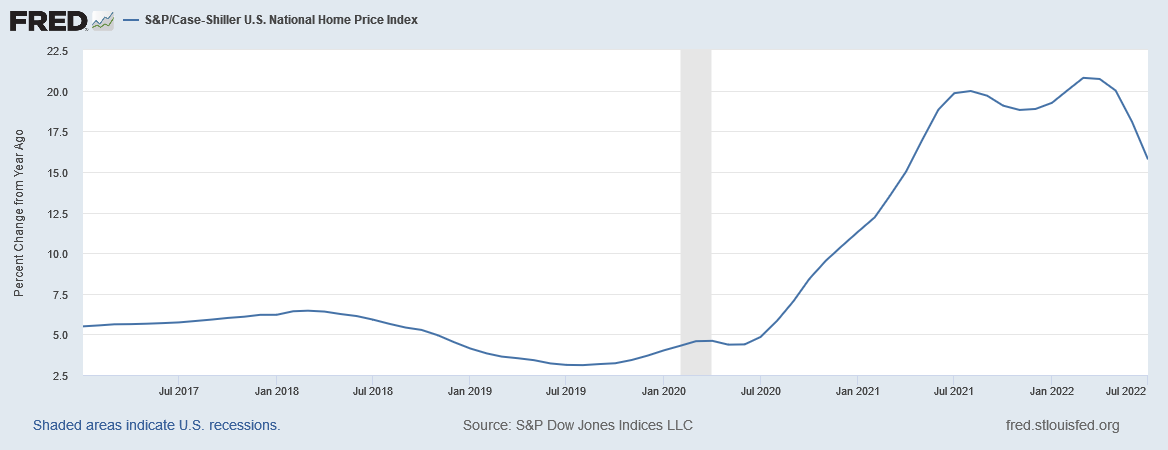

The impact of these post-pandemic housing shifts was immediately noticeable in the Case-Schiller U.S. National Home Price Index, which began a months-long climb into the stratosphere even as the US was mired in the 2020 recession.

The percent change year on year was even more dramatic.

Not until the Fed started raising interest rates in March did the housing market show any significant signs of cooling.

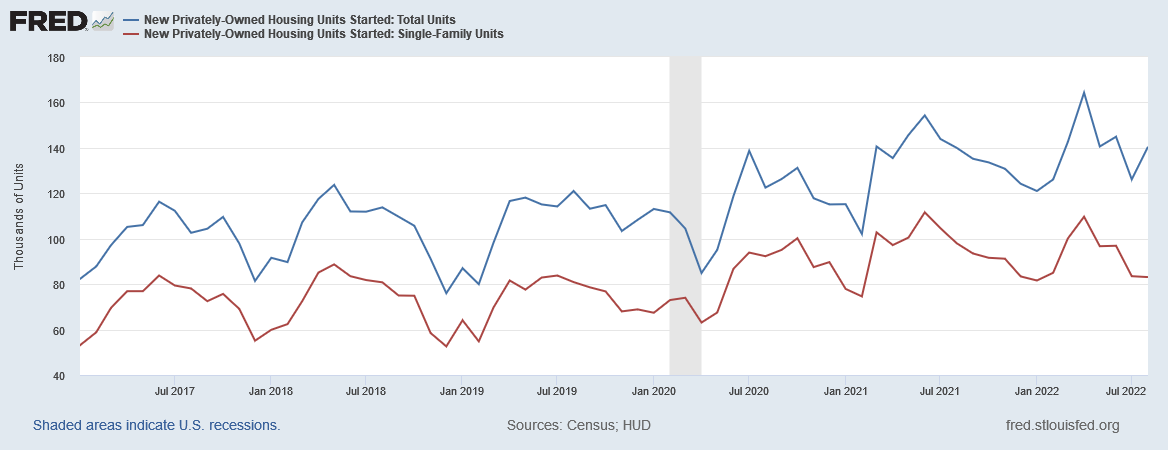

For a time, new housing starts kept the rising in housing prices within the housing market.

That trend exhausted itself in 2021, and rents begain to rise—thus leading to a rise in shelter price inflation.

The CPI Metrics Are Trailing Indicators

To fully comprehend what has been happening within both residential rental and housing markets, one must also realize that the shelter metrics within the Consumer Price Index are actually trailing indicators. Given that the nature of residential rentals is that one locks in a rental rate for a pre-set duration of a lease, increases in rents take time to show up within the CPI metrics.

Thus, while shelter price inflation within the CPI looks bad enough, when one considers the leading indicator data from private-sector reports and analytics, one quickly sees that the trend in rents has been far worse—and shelter price inflation will be far higher.

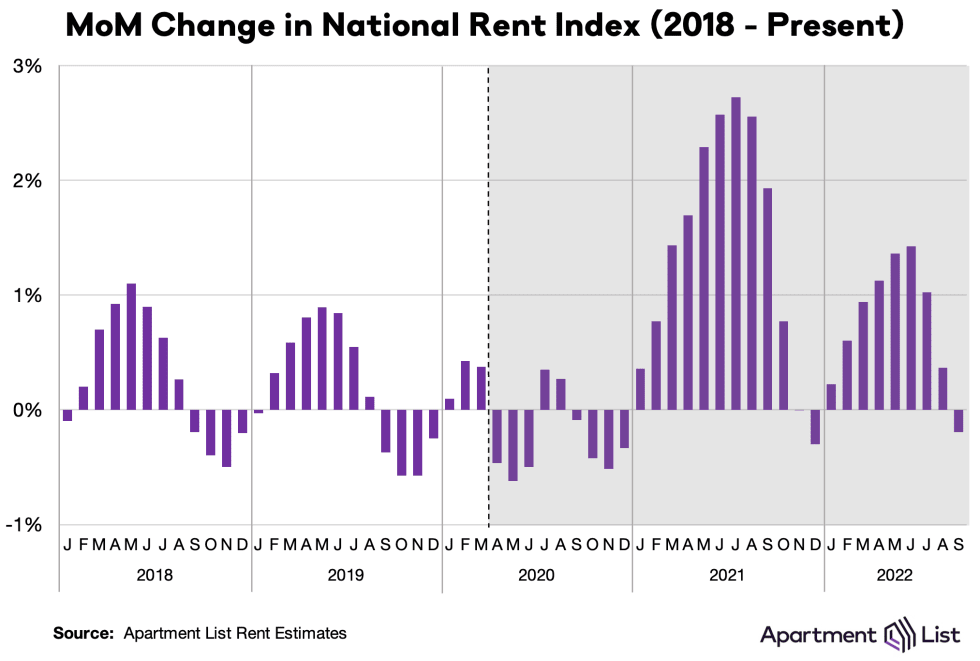

In the October Apartment List National Rent Report, median apartment rents declined for the first time all year, dropping incrementally by 0.2%.

Welcome to the October 2022 Apartment List National Rent Report. Our national index fell by 0.2 percent over the course of September, marking the first time this year that the national median rent has declined month-over-month. The timing of this slight dip in rents is consistent with a seasonal trend that was typical in pre-pandemic years. Assuming that trend continues, it is likely that rents will continue falling in the coming months as we enter the winter slow season for the rental market.

As the Apartment List Report’s chart shows, as steep as rental rate rises have been in 2022, 2021 was much, much worse, reflecting the 17.6% increase in apartment rental rates for all of 2021, as opposed to the still-steep but considerably smaller increase year-to-date of 6.8% for 2022 thus far.

While the Apartment List report contains signs that shelter price inflation may be peaking, because of the time lag between that report and the CPI shelter price inflation metrics, the CPI metrics are still showing significant month-on-month increases, and will for the next few months even if shelter price inflation has started to cool.

The Fallout: Rising Evictions

As rental rates increase in this country, so too is another grim metric: evictions. With inflation steadily eroding worker paychecks, rent affordability is also being inexorably eroded, with evictions the inevitable result, as people increasingly fail to stay current on their apartment rent.

In Houston, Texas, as various eviction moratoria lapsed, the pace of eviction filings and evictions began rising in the summer of 2021, and has steadily increased through 2022 thus far.

New York is another market where evictions have trended up since last summer, although they are so far below the historical average for that market.

While evictions are a dynamic unique to individual local markets, and thus it is not possible to extrapolate a true nationwide trend, the grim reality is that there are many markets like Houston and New York where people are losing their homes to eviction.

With cities like Houston already experiencing a 5.8% increase in homelessness in 2022 from 2021, it seems quite likely that a rising eviction rate is only going to exacerbate that trend.

A March 16 news release from the coalition reported more than 3,200 people were experiencing homelessness during the January count, with about 1,700 in shelters and 1,500 who were unsheltered. Overall, the number of people experiencing homelessness rose 5.8% from the 2021 count, but the 2022 unsheltered and sheltered numbers both saw a decline from 2020 figures.

Unlike evictions, increasing homelessness is a national trend, and a grim one.

Shelters across the U.S. are reporting a surge in people looking for help, with wait lists doubling or tripling in recent months. The number of homeless people outside of shelters is also probably rising, experts say. Some of them live in encampments, which have popped up in parks and other public spaces in major cities from Washington, D.C., to Seattle since the pandemic began.

Like Food, Shelter Has No Substitute

Like food, and unlike most other metrics within the Consumer Price Index, shelter has no good substitutes. If one loses one’s house, or is evicted from an apartment, absent friends or family willing to help out, homeless is the immediate consequence.

As I have noted previously, there is a direct path from shelter price inflation to shelter insecurity to homelessness. In 2022, an increasing number of people are heading down that path in this country.

Yet even though there are signs that, as with housing prices, residential rental rates in this country have at last peaked and may be beginning to cool, the reality is that the damage has been done. Rents have risen dramatically over the past 18 months, and a period of shelter price disinflation will not alter the reality that shelter in 2022 is considerably more expensive than in 2021 or 2020. A period of shelter price disinflation will not alter the reality that being able to afford shelter is becoming increasingly difficult for many people, and impossible for a rising subset of that group.

Perversely, the job loss that the recession the Fed is hell-bent on creating will not make shelter insecurity any better—it is far more likely to make it much much worse. Only a return to actual prosperity, and to incomes which grow above the rate of consumer price inflation, can hope to make any appreciable alteration in the trajectories of shelter insecurity and homelessness.

If we are lucky, shelter price inflation is at last starting to cool, following the same trend in housing prices. Yet even if we are lucky, the damage of shelter price inflation, and its consequences of rising shelter insecurity and rising homelessness will be many months resolving themselves.

One shudders to think of what the trends will be if we are not lucky.

Warnock, R., and L. Szini. What’s Driving Up Rent Prices This Year? 24 Aug. 2021, https://www.apartmentlist.com/research/whats-driving-up-rent-prices-this-year.