Spiraling Down Into Stagflation

Is The World Economy Headed For A Global "Lost Decade"?

Albert Einstein is apocryphally credited with saying “In theory, theory and reality are the same. In reality, theory and reality are different.”1

The same can be said for media narratives and the realities they purport to describe. According to most any media narrative (both corporate media and alternative media), the reality of any situation is exactly as they describe it to be. In reality things tend to be…different.

Case in point: last week oil market analysts were projecting a coming reversal in the market, with supplies tightening dramatically.

The imbalance between oil supply and demand is likely to reverse going into the summer, says one analyst.

"Currently, the global oil market is probably slightly oversupplied. It's going to flip to being undersupplied sometime in the late second quarter or early third quarter," Tortoise portfolio manager Rob Thummel told Yahoo Finance

"When the oil market is undersupplied, typically you see a positive price response. So we would expect oil prices to rise a bit," said Thummel.

Yet just a couple days later, market data pointed to an apparent decline in oil demand.

Crude markets saw scant support as recent data pointed to worsening economic conditions in the U.S. and China - the world’s two biggest oil consumers. This pushed up concerns that oil demand will see a much slower-than-expected recovery this year, weighing on prices.

While expectations continue to be for increased oil demand and tightening supply, reality continues to underperform expectations.

If oil markets are any gauge for the overall world economy, deepening recession and even stagflation are becoming dominant themes, which could leave the global economy trapped in an extended period of stagnation.

Indeed, when we look at the benchmark prices for crude oil, what we are seeing currently is an extended downward trend in oil prices, even as the spot price fluctuates up periodically.

OPEC+ production cuts and even the war over Ukraine have not thus far proven sufficient to constrain supply relative to demand, resulting is a constant downward pressure on oil prices. Even though prices are showing some signs of stability recently, they are a long way from confirming any “bottoming out” of the price decline.

Even the recent announcement by the US to add 3 million barrels of crude to the Strategic Petroleum Reserve has not completely arrested the downward trend.

The U.S. Department of Energy said Monday it plans to buy as much as 3M barrels of crude oil for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to begin refilling the emergency reserve that has fallen to its lowest level since 1983.

Crude oil prices extended gains in post-settlement trading on news of the plan, with June WTI futures (CL1:COM) jumping to $71.48/bbl before pulling back, after closing +1.5% at $71.11/bbl, snapping a three-session losing streak.

Either the existing oil glut is far more extensive than has been reported thus far, or oil demand in the global economy is slipping more than is being acknowledged.

On the one hand, the International Energy Agency continues to promote optimistic forecasts of oil demand growth in the future

World oil demand is forecast to rise by 2.2 mb/d year-on-year in 2023 to an average 102 mb/d, 200 kb/d above last month’s Report. China’s demand recovery continues to surpass expectations, with the country setting an all-time record in March at 16 mb/d. While the OECD is set to return to growth in 2Q23, its average 2023 increase of 350 kb/d pales in comparison with 1.9 mb/d in non-OECD gains.

On the other hand, the reality of oil demand in the present is that it remains extremely soft.

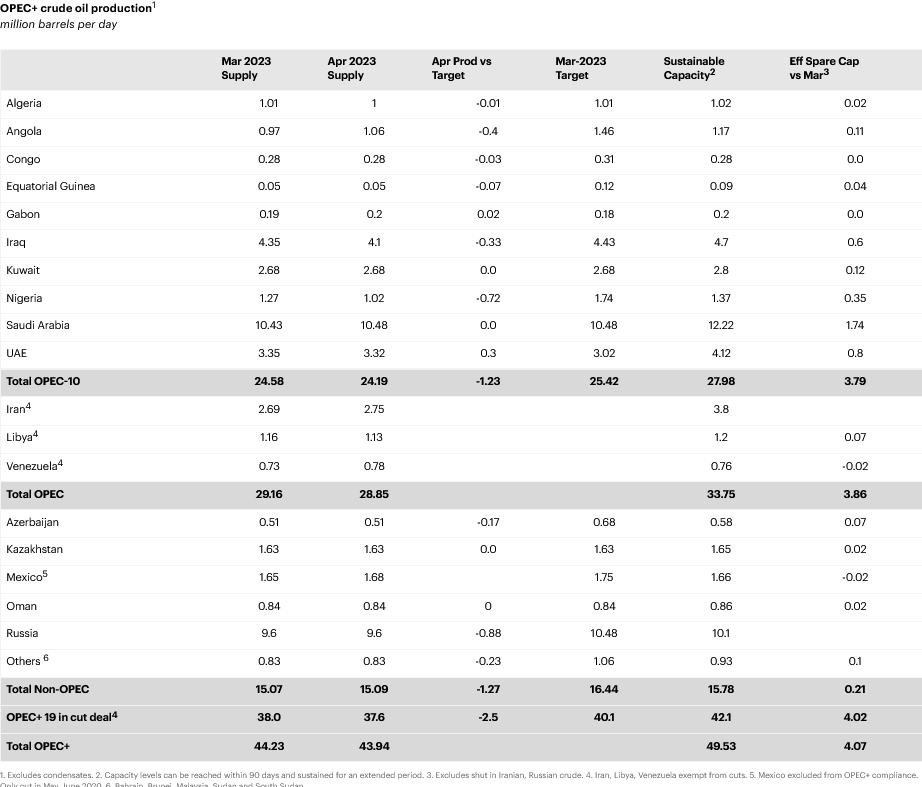

Not only is global oil production well below estimated sustainable capacity, among the OPEC nations April production is well below March production, with both months well below the target volumes the cartel had set for its outlets.

Yet despite these seeming production shortfalls, the price of oil has not been pushed up, but rather allowed to keep drifting down.

The media narrative may be one of rising demand and rising prices, but the reality appears to be one of falling demand and falling prices—and that reality suggests that economic narratives including that of a robust “reopening” of China’s economy post-Zero COVID as well as the trope of the world’s leading economies managing to stay out of recession.

Despite the media narratives, the data coming out of China does not at all paint an optimistic economic picture.

Officially, China has been touting its April economic data as proof of that country’s return to economic growth and prosperity.

In April, under the strong leadership of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core, all regions and departments firmly implemented the decisions and arrangements made by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council, adhered to the general principle of pursuing progress while maintaining stability, fully and faithfully applied the new development philosophy on all fronts, accelerated efforts to create a new pattern of development, and ensured early and coordinated effects of macro policies. As the economic and social activities have fully returned to normal, the year-on-year growth for most production and demand indicators improved, services and consumption witnessed fast recovery, and employment and prices were generally stable. The economy sustained the good momentum for recovery.

Yet at the same time, the Chinese yuan has been declining against the dollar, in large part because of market perceptions that its economic data has been “weak” and disappointing.

The Chinese yuan traded at an over two-month low against the dollar on Monday, and was once again within spitting distance of the key 7 level against the greenback following a string of weak economic data in recent weeks.

The yuan fell 0.1% to 6.9620 to the dollar after falling consistently for the past seven sessions. The offshore yuan, which better reflects global market sentiment towards the currency, traded at 6.9713 to the dollar.

As of last Thursday, the yuan broke through the 7 yuan to the dollar threshold, and has thus far stabilized just above that level.

For all the corporate media chatter about a “rebound” in the Chinese economy, economic warning signals continue to accumulate.

Surprisingly, China’s aviation industry incurred even more severe losses (217.44 billion yuan) in 2022 than in 2021 (137.46 billion yuan).

China’s unemployment rate for the age bracket 16-24 worsened to 20.4%, even as overall unemployment trended down.

While industrial production growth of 5.6% in April exceeded March’s growth rate of 3.9%, it was almost half of what analysts had expected (10.9%).

Retail sales grew at 18.4% in April, well above the March rate of 10.6% but off the analysts expected rate of 21%.

A resurgent Chinese economy is essential for forecasts of oil supplies tightening and oil price recovery later this year. So far the Chinese economy is coming in well below the anticipated “resurgent level”.

Additionally, Chinese firms which have defaulted on their offshore dollar debt are being forcibly liquidated when they fail to present an acceptable restructuring plan to their creditors, as recently happened to Dangdai International Investments Ltd., a debt issuance vehicle of Wuhan Dangdai Science & Technology Industries (Group) Co.

The court’s decision to issue the so-called winding-up order came just two weeks after a Chinese property developer received an identical blow after losing its own legal battle. While repayment failures in China’s offshore market have surged amid an unprecedented housing crisis, the vast majority of defaulters have been slow to respond to creditors’ demands for a restructuring roadmap, raising the risk of court-imposed liquidation and weakening long-term investor confidence in China Inc.

Between the defaults and the forced liquidations, China, Inc. is rapidly losing its luster among offshore investors.

On nearly every front and by most metrics, the Chinese economy is softening, and may very well be already contracting. Some economists are already forecasting Chinese consumer prices to tip from very mild inflation rates to outright deflation.

Standard Chartered has explained they expect inflation levels to hit 0% in the next months, “as a crude-oil price spike in the first half of 2022 created a high comparison base.” However, even with a slow inflation level, the bank has predicted a growth rate of more than 5% without adjusting interest rates, which are now at 1%.

Experts who are worried about the possibility of deflation have made different proposals to avoid it. Li Daokui, a professor of economics at Tsinghua University and former member of the PBOC advisory board, has called for the government to deliver cash handouts to citizens to spur demand. Last month, Li stated.

Outright consumer price deflation could very well prove to be the harbinger of a period of economic stagnation, a phenomenon not unlike Japan’s “Lost Decade” of the 1990s2.

The Lost Decade is commonly used to describe the decade of the 1990s in Japan, a period of economic stagnation which became one of the longest-running economic crises in recorded history. Later decades are also included in some definitions, with the period from 1991-2011 (or even 1991-2021) sometimes also referred to as Japan's Lost Decades.

This much is certain: if China’s economy is indeed headed for a period of economic stagnation and decline, expectations that China will push oil demand and oil prices higher are not going to be met in even the slightest degree.

China’s growing economic woes are compounding the economic distress being experienced by a number of developing countries who are heavily indebted to China.

Whether due to lack of significant prior experience with sovereign debt markets or a pressing need to be repaid on outstanding loans, China’s unforgiving stance on outstanding government loans is pushing nearly a dozen countries into debt default.

An Associated Press analysis of a dozen countries most indebted to China — including Pakistan, Kenya, Zambia, Laos and Mongolia — found paying back that debt is consuming an ever-greater amount of the tax revenue needed to keep schools open, provide electricity and pay for food and fuel. And it’s draining foreign currency reserves these countries use to pay interest on those loans, leaving some with just months before that money is gone.

Behind the scenes is China’s reluctance to forgive debt and its extreme secrecy about how much money it has loaned and on what terms, which has kept other major lenders from stepping in to help. On top of that is the recent discovery that borrowers have been required to put cash in hidden escrow accounts that push China to the front of the line of creditors to be paid.

Setting aside the obvious concerns about accountability and moral hazard in debt markets, the grim economic reality for many developing countries is that servicing their debts increasingly means not meeting their other obligations, particularly towards their own people.

Yet by not working with indebted countries to restructure and renegotiate the outstanding debt, China may be precipitating the very economic upheaval and potential collapse that would only ensure its loans never got repaid.

China’s unwillingness to take big losses on the hundreds of billions of dollars it is owed, as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank have urged, has left many countries on a treadmill of paying back interest, which stifles the economic growth that would help them pay off the debt.

Foreign cash reserves have dropped in 10 of the dozen countries in AP’s analysis, down an average 25% in just a year. They have plunged more than 50% in Pakistan and the Republic of Congo. Without a bailout, several countries have only months left of foreign cash to pay for food, fuel and other essential imports. Mongolia has eight months left. Pakistan and Ethiopia about two.

Worse still, some of China’s debt management practices for dealing with distressed borrowers arguably make the situation much worse. Rather than following the customary sovereign debt practices of the IMF and the World Bank, China has frequently adopted secretive lending techniques that arguably service current debt obligations, but at the cost of adding more loans at greater interest, leaving indebted countries even deeper in the hole.

Meanwhile, Beijing has taken on a new kind of hidden lending that has added to the confusion and distrust. Parks and others found that China’s central bank has effectively been lending tens of billions of dollars through what appear as ordinary foreign currency exchanges.

Foreign currency exchanges, called swaps, allow countries to essentially borrow more widely used currencies like the U.S. dollar to plug temporary shortages in foreign reserves. They are intended for liquidity purposes, not to build things, and last for only a few months.

But China’s swaps mimic loans by lasting years and charging higher-than-normal interest rates. And importantly, they don’t show up on the books as loans that would add to a country’s debt total.

Mongolia has taken out $1.8 billion annually in such swaps for years, an amount equivalent to 14% of its annual economic output. Pakistan has taken out nearly $3.6 billion annually for years and Laos $300 million .

The swaps can help stave off default by replenishing currency reserves, but they pile more loans on top of old ones and can make a collapse much worse, akin to what happened in the runup to 2009 financial crisis when U.S. banks kept offering ever-bigger mortgages to homeowners who couldn’t afford the first one.

Whether the more dire projections are likely to occur, this much seems clear: the economies of several developing countries are already either contracting or on the brink of an inevitable contraction. What they are not doing is growing.

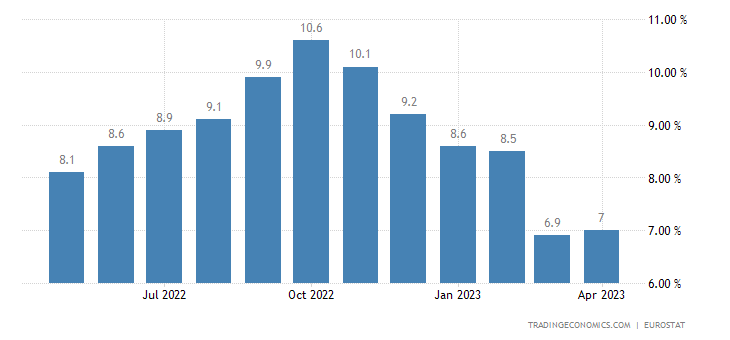

Europe seems poised to round out global economic woes, as its economies continue to suffer from economic upheavals brought on by the war in Ukraine and resultant sanctions on Russia.

Germany, long a leader on the continent, is leading the way into a deeper recession, as investor confidence plummeted in April.

Investors’ confidence in Germany waned for a third month, reigniting fears that Europe’s largest economy is heading for a recession.

The ZEW institute’s gauge of expectations fell to -10.7 in May from 4.1 in April — the first sub-zero reading of 2023. Economists polled by Bloomberg had expected a decline to -5. An index of current conditions also deteriorated.

The waning of investor confidence comes on the heels of plummeting industrial production in March, falling 3.4% month on month, a stunning reversal from February’s increase of 2.1% month on month.

In March 2023, production in industry in real terms was down by 3.4% on the previous month on a price, seasonally and calendar adjusted basis, according to provisional data provided by the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis). This decrease follows an increase of production in industry by 2.1% in February 2023 (provisional figure: 2.0%). Considering the 1st quarter of the year 2023, production was 2.5% higher compared with the 4th quarter of the previous year.

Nor is the outlook for German manufacturing likely to improve in the near future, as new orders in the sector plunged 10.7% month on month in March.

Real (price adjusted) new orders in manufacturing fell by 10.7% on a seasonally and calendar adjusted basis in March 2023 compared with February 2023, according to provisional results of the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis). This is the strongest decline since the breaking down of new orders in April 2020 as a result of the corona pandemic. The decrease follows an increase of new orders by 4.5% in February 2023 (provisional figure: +4.8%). Considering the first quarter of the year 2023, new orders were 0.2% higher than they were in the last quarter of the previous year. Excluding large-scale orders, there was a decrease of 7.7% in March 2023 compared to the previous month.

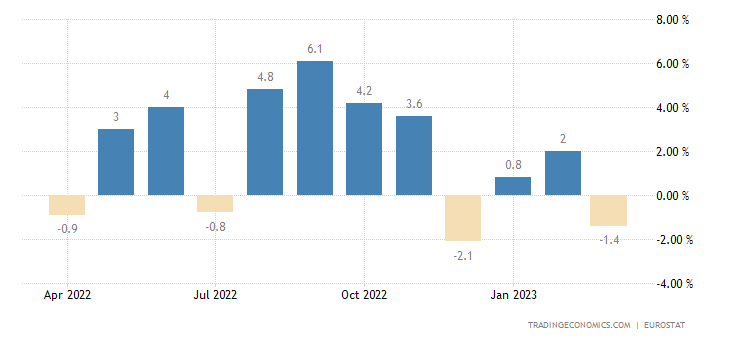

Germany’s metrics reflected the larger European economy, as across the Euro Area industrial production in March dropped 1.4% month on month.

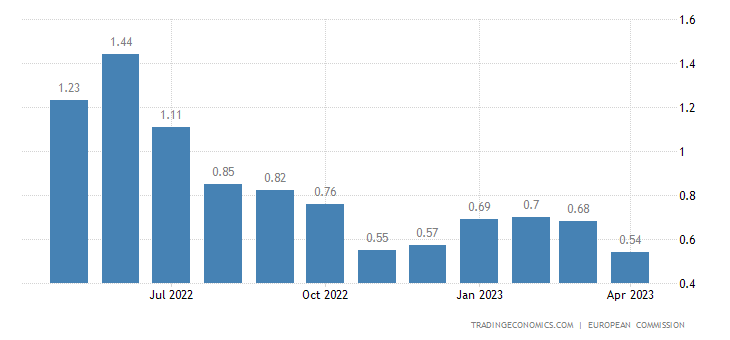

Business confidence dropped as well, declining to .54 in April from 0.68 in March.

At the same time, inflation ticked up in the Euro Area for the first time in seven months.

At the same time, much like in the United States, rising interest rates are increasing the likelihood of debt defaults as bank assets are placed under increasing stress.

European Central Bank interest rate hikes are in their final stretch, ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos told an Italian newspaper, while warning that higher borrowing costs could put stress on banks' asset quality, even if indicators so far remain healthy.

Higher interest rates mean a higher cost of capital, and a greater degree of refinancing or rolling over existing debts.

These rate hikes improve banks' lending margins but could also make it more difficult for some borrowers to repay their debts, lifting the portion of non-performing loans or NPLs.

While the ECB puts a brave face on the situation, they also concede the one sure outcome of their rate hike strategy is the same as that for the Federal Reserve: recession.

"The combination of a slowing economy and the interest rate hikes will bring a rise in the cost of funding for banks and possibly an increase in non-performing loans."

Europe. China. Developing countries. In every part of the globe economies are weakening, sputtering, contracting, even collapsing, in spite of what media narratives state.

Regardless of what various experts and analysts portentously proclaim about parts of the world having “avoided a recession”, beneath their glossed-up headline numbers and tailored rhetoric, the reality remains that the global economy is already in recession.

The reality is that those places not saddled with steep inflation are facing deflation.

Which means that the expectations of some that China or some other part of the world economy will miraculously lead the world into renewed economic growth3 and prosperity for all are delusional pipe dreams.

It is cold comfort that countries are not hurtling headlong into economic collapse. While the current trends do not end in that abyss, neither do they end with an improving situation any time soon.

Barring a sea change in the global economy—barring a sea change in how government “experts” apprehend their economic roles—the world as a whole is steadily spiraling into stagflation. Governments everywhere have failed completely in their attempts to manage (and micromanage) their countries’ economy, with the result that most economies are doomed to stumble along for the foreseeable future, stuck in an underperforming dysfunction.

Unless and until something changes on the world stage, at least one “lost decade” awaits.

As with so many pithy quotes, the actual quote as well as its attribution is a matter of some debate. The form that actually can be sourced and attributed is “…in theory there is no difference between theory and practice, while in practice there is,” which has been credited to Yale student Benjamin Brewster in the February 1882 edition of The Yale Literary Magazine. (Quote Investigator. In Theory There Is No Difference Between Theory and Practice, While In Practice There Is. 14 Apr. 2018, https://quoteinvestigator.com/2018/04/14/theory/)

Halton, C. “Lost Decade in Japan: History and Causes”, Investopedia. 27 Sept. 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/lost-decade.asp.

International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery. Apr. 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/04/11/world-economic-outlook-april-2023.

So as goes the US, goes the world.

China might be leading the world, but their quality control sucks.

Ever try to fix a Chinese VCR? The Japanese ones are imminently repairable.

Appreciate your posts, you are a real treasure here.

One of the best things about your Substack is the wealth of hard, factual data you continuously unearth. It supports your analysis and has many times changed my view of what’s developing (for example, I worried about the imposition of CBDCs until you explained how they simply cannot work). I agree, the world is headed for a long period of hard economic times, as your data irrefutably shows. It’s the details you provide that make the difference. For example, about ten years ago, I read an article in Wired magazine about China’s Belt and Road Initiative, forging economic ties with dozens of underdeveloped countries in ways that made me worried about those countries becoming military allies with China in any conflict. But your explanation of the unforgiving lending conditions flips my understanding to realizing that they are more likely to end up antagonist to China! What a difference a little knowledge of harsh lending practices can make!

Your columns invariably stir up plenty of speculations and questions. In your digging for data, have you encountered any intriguing strategies countries have for dealing with the developing economic picture? For example, does China have a stated ‘plan’ for fixing their 20.4 % unemployment rate amongst those 16-24 years old? Has Germany come up with any viable tactics to deal with their economic woes?

The absolute best thing about your column is your brilliant analysis, Mr. Kust. Seriously, I wish you were employed at Cabinet level; this country needs you!