The Fed Stands Pat, So Wall Street Pouts

Jay Powell Does Not Know What To Do Next Or When To Do It

Jay Powell’s biggest problem is that he does not know how to just say “I don’t know.” Perhaps if he mastered that simple sentence, Wall Street might be more forgiving of his directionless stance on the federal funds rate and on monetary policy overall.

Case in point: yesterday’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) statement standing pat on the federal funds rate, and Jay Powell’s rambling presser after that statement’s release.

In support of its goals, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5-1/4 to 5-1/2 percent. In considering any adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks. The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans. The Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.

In his opening remarks to his regular press conference after the FOMC makes a policy statement, Powell did his Washingtonian best to stake out both sides of each monetary policy position:

We believe that our policy rate is likely at its peak for this tightening cycle and that, if the economy evolves broadly as expected, it will likely be appropriate to begin dialing back policy restraint at some point this year. But the economy has surprised forecasters in many ways since the pandemic, and ongoing progress toward our 2 percent inflation objective is not assured. The economic outlook is uncertain, and we remain highly attentive to inflation risks. We are prepared to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate for longer, if appropriate.

In other words, the Fed is through raising the federal funds rate and will start cutting that rate. However, it won’t cut until the economy shows that cuts are appropriate, which could mean the Fed will raise rates if the economy goes off on a tangent as it has shown itself able to to do. The economy could shrink, or it could grow, which means inflation could rise or could fall, and so the Fed will raise or lower rates to match whatever the economy does or does not do.

You understood all that, right? If you did, you are probably doing better than Jay Powell. Understanding is rarely his forte.

Powell’s answers to the media’s questions did not improve from his befuddled opening remarks. From the start he seemed more interested in bobbing and weaving than in actually answering questions.

NEW YORK TIMES: In the statement and remarks, you note that you don't want to cut interest rates without greater confidence that inflation is coming down fully. What do you need to see at this point to gain that confidence? How are you weighing recent strong growth in consumer spending data against the sort of solid inflation progress you have been seeing?

POWELL: What are we looking toward for greater confidence. We have confidence and we are looking for confidence that inflation is moving sustainably at 2%. We have confidence that has been increasing but we want greater confidence. What do we want to see? We want to see more good data. It is not that we are looking for better data but continuation of the better data. Six months of good inflation data, but the question is, that six months of good inflation data, is it sending us a true signal that we are, in fact, on the path -- sustainable path down to 2% inflation.

The answer will come from some more data that is also good data. It is not that the 6 month data isn't low enough. It is. But it is a question of can we take that with confidence that we are moving sustainably on to 2%. That is what we are thinking about.

In terms of growth, we have had strong growth. Take a step back. We have had strong growth, very strong growth last year, going right into the 4th quarter. And yet we have had a very strong labor market, and we have had inflation coming down. So, I think, whereas a year ago we were thinking we needed to see some softening in economic activity, that hasn't been the case.

So, I think we look at stronger growth -- we don't look at it as a problem. I think at this point we want to see strong growth and a strong labor market. We are not looking for a weaker labor market but for inflation to continue to come down as it has been the last six months.

Of course, the problem with Powell’s response particularly as regards inflation is that it stands at odds with the existing data sets on inflation.

When we look at the year on year shift in consumer price inflation per the PCE Price Index, we see that the trend on inflation is still down.

However, the flattening out of headline inflation from November to December at a minimum suggests that disinflation may be bottoming out, and at a level above the Federal Reserve’s 2% holy grail target.

Yet the challenge with the “cooling inflation” narrative is that, month on month, the PCE Price Index shows inflation rates significantly higher than the prior two months.

Inflation arguably was cooling from September through November. In December that trend abruptly ended.

If Powell needs to see six months of “good data”, he has a problem, because right now he does not even have one month of “good data”.

Powell’s problem, of course, is that he clearly does not know what inflation is doing right now, let alone over the past six months.

Of course, inflation is not the only data set where Powell does not know the realities. He insists on pushing the canard that American labor markets are “strong”.

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL: This morning's 4th quarter report shows progress payroll growth running at 4% pace. Inflation expectations are close to where they were before the inflation emergency of the last three years and you appear to have substantially cut off these two tail risks and that you judged the current policy, as well, in the restrictive territory. What good reason is there to keep policy rates above 5%. Will you really learn more waiting six weeks versus three months from now that you have avoided those two risks?

POWELL: As you know, almost every participant on the Committee believes it will be appropriate to reduce rates. For probably the reasons that you say. We feel like inflation is coming down. Growth has been strong. The labor market is strong. What we are trying to do is identify a place where we are really confident about inflation getting back down to 2% so we can then begin the process of dialing back the restrictive level.

So, overall, I think people do believe -- and as you know the median participant wrote down three rate cuts this year. But I think to get to that place where we feel comfortable starting the process, we need confirmation that inflation is, in fact, coming down, sustainably to 2%.

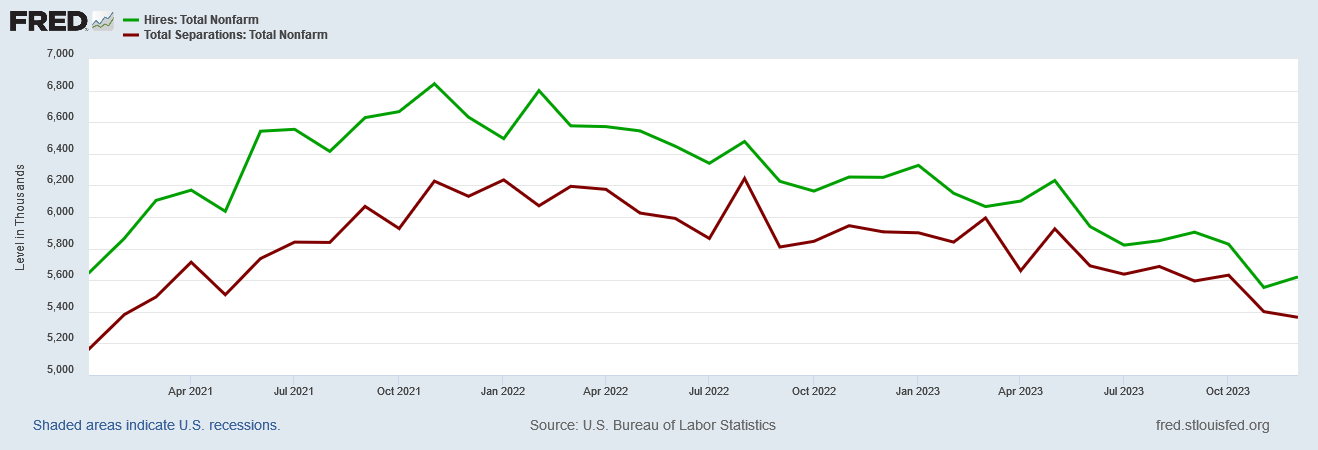

Again, the data on the labor market tells a far different story:

Moreover, even the seasonally adjusted data shows a worrisome trend: hiring is weakening relative to separations, and has been since early 2022.

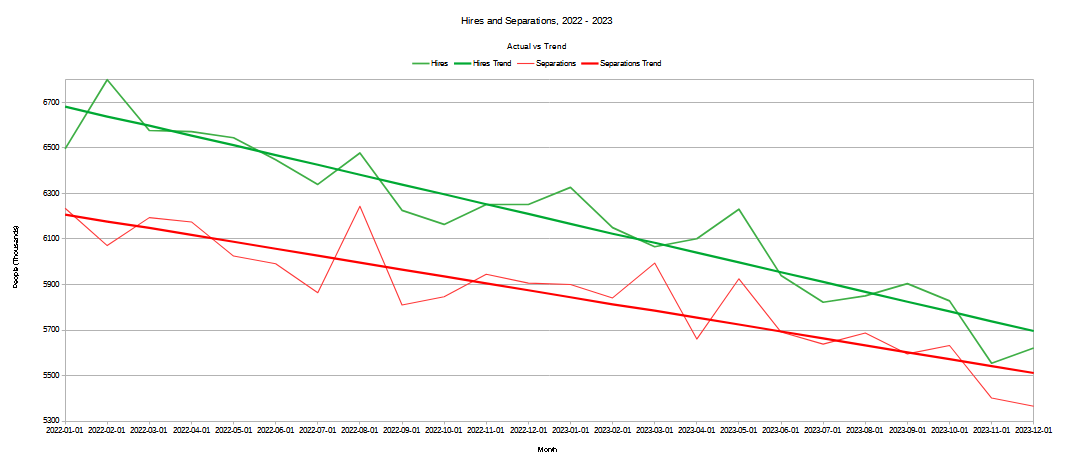

If we take a trend line on the hires and separations from January 2022 through December, 2023, we can see the steeper decline in hiring quite easily.

Not only has seasonally adjusted hiring been declining since early 2022, it has been declining faster than seasonally adjusted separations over the same period.

Only on Wall Street would declining hiring be taken as a sign of a strong labor market.

Only on Wall Street and at the Federal Reserve would declining hiring be taken as a sign of a strong labor market.

Part of Powell’s cluelessness stems from his misreading of labor force participation.

The labor market remains tight, but supply and demand conditions continue to come into better balance. Over the past three months, payroll job gains averaged 165 thousand jobs per month, a pace that is well below that seen a year ago but still strong. The unemployment rate remains low, at 3.7 percent. Strong job creation has been accompanied by an increase in the supply of workers: The labor force participation rate has moved up on balance over the past year, particularly for individuals aged 25 to 54 years, and immigration has returned to pre-pandemic levels. Nominal wage growth has been easing, and job vacancies have declined. Although the jobs-to-workers gap has narrowed, labor demand still exceeds the supply of available workers.

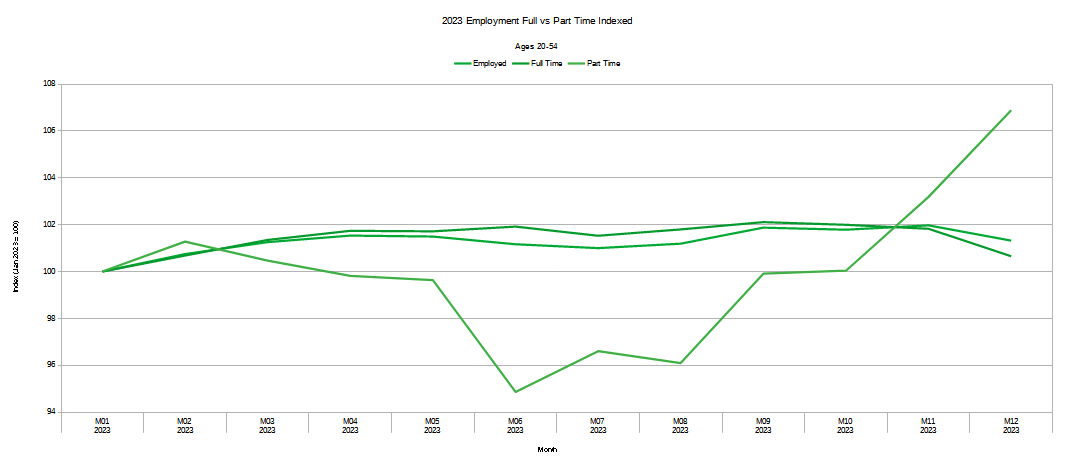

There are two key points that the Fed conveniently overlooks in the employment data for individuals aged 25-54: employment in that age cohort actually plateaued in June of last year before trending down slightly afterward, and the employment growth for the last half of the year occurred exclusively among part-time workers.

Powell apparently does not know that if people can only find part-time work, especially those in the 25-54 age bracket, that is not a “strong” labor market, nor is it a strong economy.

If a significant weakening of the labor market is one of the signs the Fed seeks before it starts cutting the federal funds rate, it is already looking past several very alarming labor signals, which means even by its own standards it has ventured into the forbidden realm of policy error. Powell does not know that, by his own criteria, the Fed should have cut rates long ago (nor does Powell realize that cutting rates would have been as ineffective as raising them has been).

Wall Street’s reaction to Powell’s mishmash of nonsense and factual error was perhaps to be expected—it did not like what Powell had to say, even though the lack of action on the federal funds rate had already been fully priced in.

Equities moved largely horizontal on the day yesterday—until after Powell’s press conference concluded.

After Powell finished his ramblings, the Dow plunged, and the rest of the equity indices followed right along.

Treasury yields reacted more favorably.

As has been the case since mid-2022, the Fed still can only exert minimal upward pressure on interest rates.

That market interest rates can find ways to trend down even as the Fed commits to keeping the federal funds rate elevated demonstrate yet again that fundamental weaknesses persist within the US economy. Wall Street knows what Powell does not—that the economy is in a parlous condition.

Ultimately, Wall Street ended the day largely frustrated with Jay Powell and his fundamental lack of clue about anything pertaining to the economy. Powell does not know what is actually taking place in the economy with respect to inflation, with respect to employment, with respect to any significant data beyond the soothing manipulated numbers of the headline economic reports from the BLS and the BEA. His unfocused and undisciplined answers yesterday proved that in spades.

Not knowing what is actually taking place in the economy, Powell has no clue when would be the ideal time to cut interest rates, or if there is any ideal time to cut interest rates (what are the odds the best rate strategy for the Fed right now is to do nothing for the next 24-36 months?). He simply does not know.

Wall Street knows that Jay Powell does not know what to do next on interest rates. Wall Street is also hoping that Powell, because of his lack of knowledge and understanding, will eventually cut the federal funds rate and bring back the era of cheap and free money.

Wall Street will likely see its hopes realized at some point. Just like Jay Powell, however, Wall Street does not know when that will happen. Unlike Jay Powell, Wall Street is not okay with that.

Usury used to be considered illegal.

I do not trust the “quasi legal Federal Reserve”