December JOLTS: Fake Job Openings Show "Little Change", Actual Hiring Shows Not So Little Decline

The "No News" Is Still Very Bad News.

If one looks at the manipulated seasonally adjusted data in the December, 2023, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey Report, there is little change.

The number of job openings changed little at 9.0 million on the last business day of December, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the month, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.6 million and 5.4 million, respectively. Within separations, quits (3.4 million) and layoffs and discharges (1.6 million) changed little. This release includes estimates of the number and rate of job openings, hires, and separations for the total nonfarm sector, by industry, and by establishment size class.

Wall Street looked at the seasonally adjusted data and decided to look no further. The BLS had mangled any actual labor shifts sufficiently to allow Wall Street to overlook them entirely, while pretending the data showed a “resilient” labor market.

U.S. job openings unexpectedly rose in December to the highest level in three months, underscoring the resilience of the labor market even in the face of higher interest rates.

The Labor Department said Tuesday there were 9 million job openings in December, an increase from the upward revised 8.9 million openings reported the previous month. Economists surveyed by Refinitiv expected a reading of 8.7 million.

"The report boils down to no news is good news," said Robert Frick, corporate economist with Navy Federal Credit Union. "Job openings are still a healthy level above those seeking work, and the other numbers remain where a healthy labor market should find them. While openings did tick up, the increase is well within the margin of error."

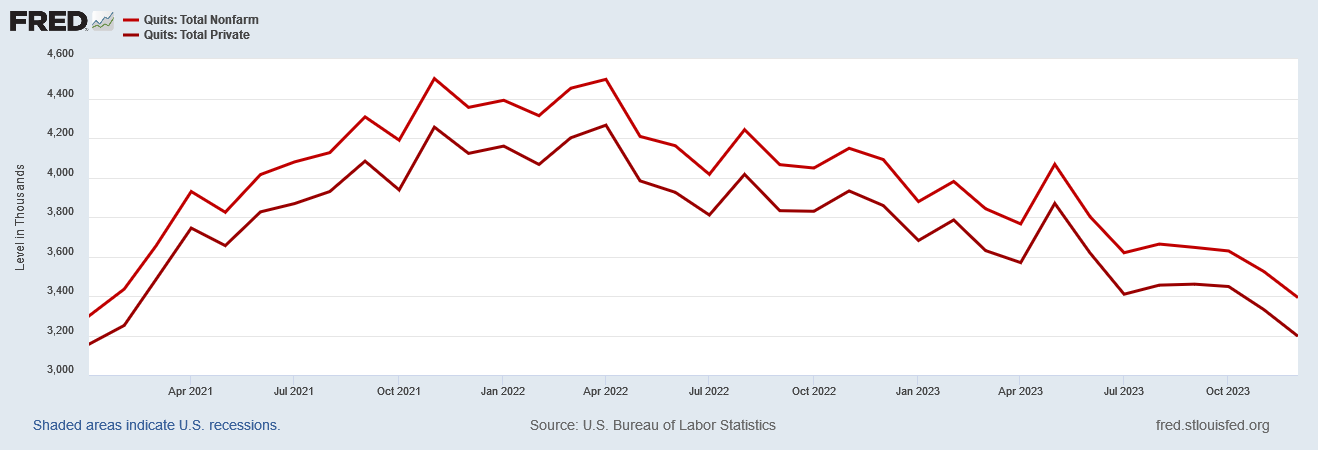

The giveaway this month that the job openings numbers don’t mean a thing: the fact that job quits declined significantly again this month—indicating workers are not at all confident about the current job market. This stance is, of course, completely contradictory to a labor market with ample job openings to encourage job hopping.

Workers called it quits less frequently in 2023, a sign confidence in the labor market is falling as the U.S. economy is expected to slow and Americans are taking longer to find new jobs.

That is a turnaround from the years just after the pandemic took hold, when resignations surged and companies faced labor shortages. In 2021 and 2022, employers put up billboards seeking workers, eliminated background checks, offered big raises and handed out signing bonuses to restaurant and factory workers.

Last year, workers quit 5.6 million fewer jobs from January through November than the same period in 2022—a decline of 12%, according to the Labor Department. December and 2023 data on quits, hiring and job openings will be released at 10 a.m. Eastern time on Tuesday.

Workers are intuiting the truth about America’s labor markets: they remain toxic rather than tight, and workers are increasingly nervous about their future prospects.

None of which is a positive trend for the US economy.

If we focus on the seasonally adjusted data exclusively, as does Wall Street, we could be forgiven for thinking there was not a lot of change in the JOLTS data for December—at the seasonally adjusted level, there simply was not a lot of change.

However, if one looks at the raw data, there is a fair bit of change, and not of a good variety.

Hiring declined significantly for the second straight month, while separations increased.

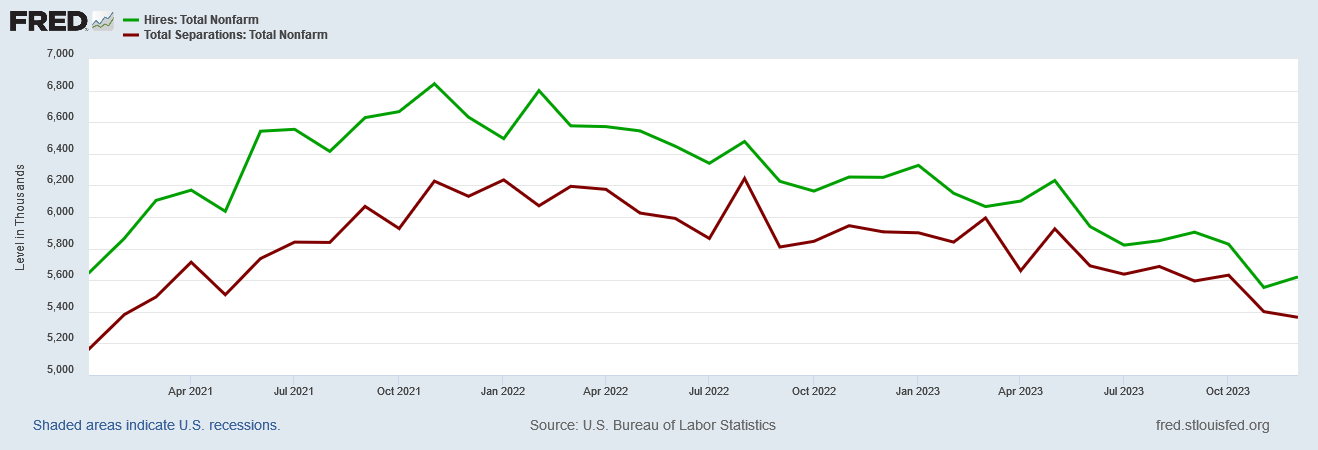

Moreover, even the seasonally adjusted data shows a worrisome trend: hiring is weakening relative to separations, and has been since early 2022.

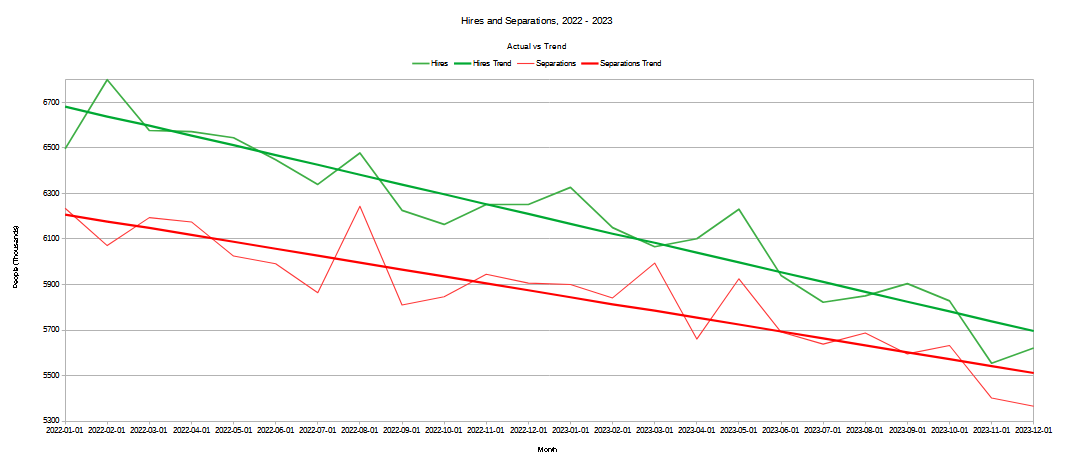

If we take a trend line on the hires and separations from January 2022 through December, 2023, we can see the steeper decline in hiring quite easily.

Not only has seasonally adjusted hiring been declining since early 2022, it has been declining faster than seasonally adjusted separations over the same period.

Only on Wall Street would declining hiring be taken as a sign of a strong labor market.

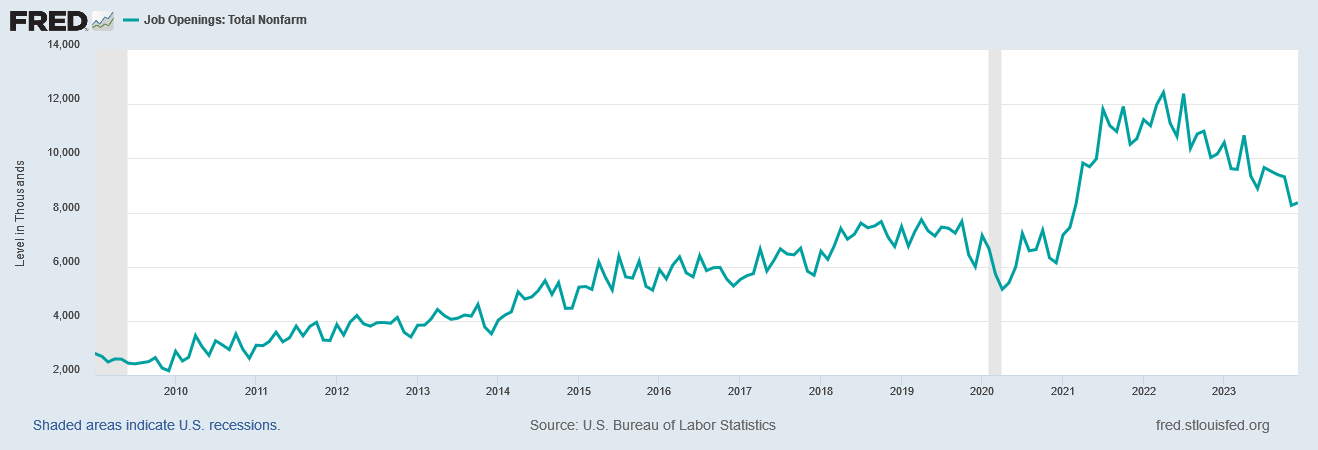

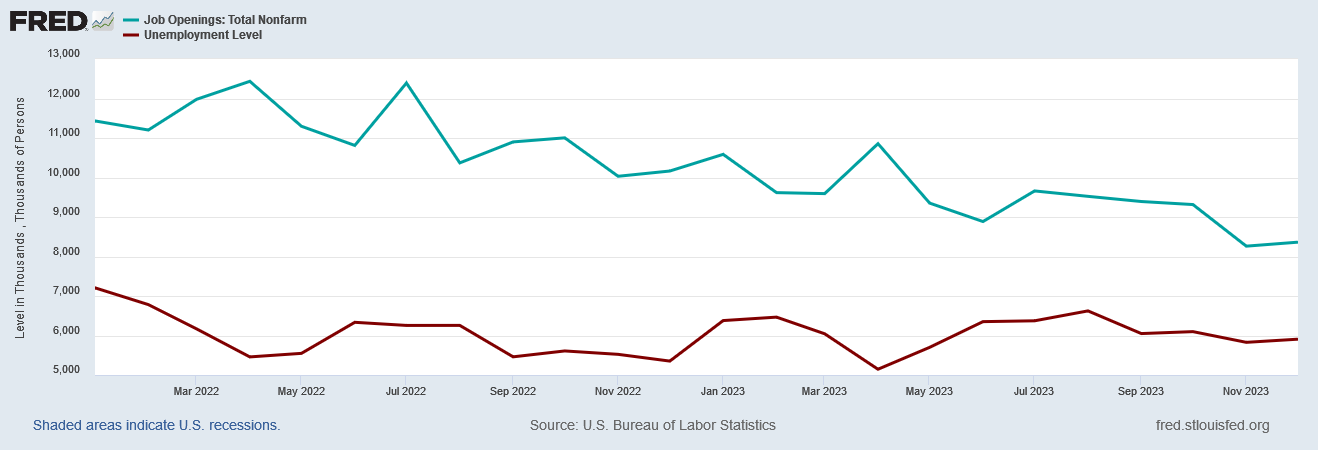

Even the unadjusted job openings data itself has been declining over the past two years.

This decline is significant, because another aspect of the job openings data which gets neglected by Wall Street and the corporate media is the extent to which the job openings numbers have been anomalously high since approximately one year after the 2020 Pandemic Panic Recession.

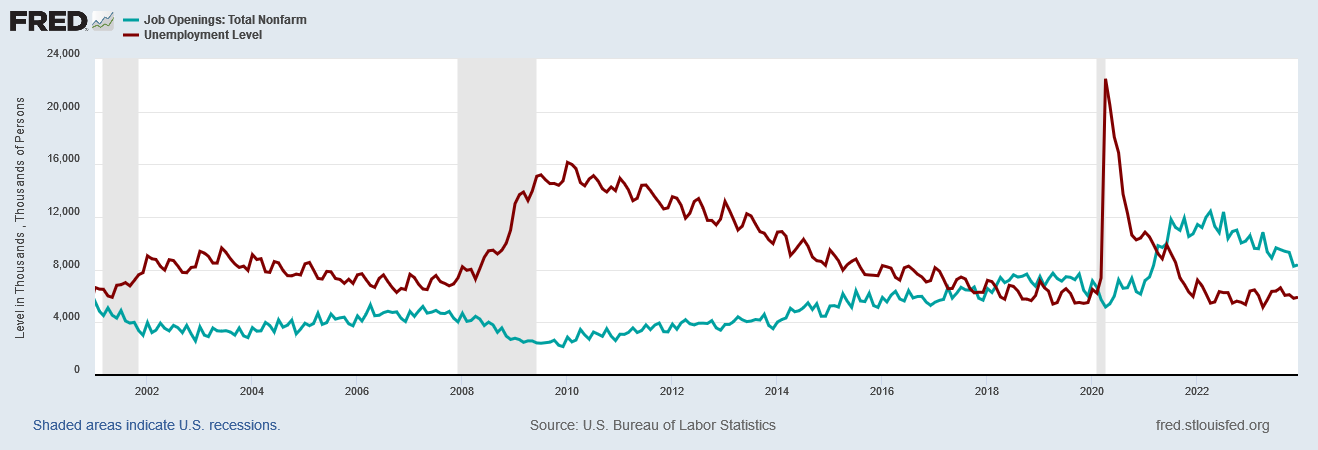

If we look at the job openings data since before the 2001 recession, we see that job openings historically have run below the unemployment level. It was not until April of 2018 that job openings exceeded the unemployment level by even a little bit, and up until the 2020 Pandemic Panic Recession, job openings exceeded unemployment levels by only a very small margin.

Against this historical backdrop, the decline in job openings since the beginning of 2022 very likely includes the statistically inevitable “reversion to mean”, where the historical patterns eventually reassert themselves.

The fact that hiring is declining in the same time frame also underscores the degree to which the job openings data is simply not real and not reliable.

Also indicating that the job openings data is artificially inflated is the reality that the cohort of workers not in the labor force has been rising throughout the same period that job openings and hiring have been declining.

Not only is hiring steadily getting weaker in US labor markets, so is the labor force participation rate.

Even if we focus on just the seasonally adjusted data, the dysfunction in the labor markets is unmistakable. As was the case in November, one has to go back to early 2018 to find a sustained hiring rate to match the December 2023 number.

Since January, 2020, hiring in the US has declined by 7.3%—and that is inclusive of the December uptick in the seasonally adjusted data.

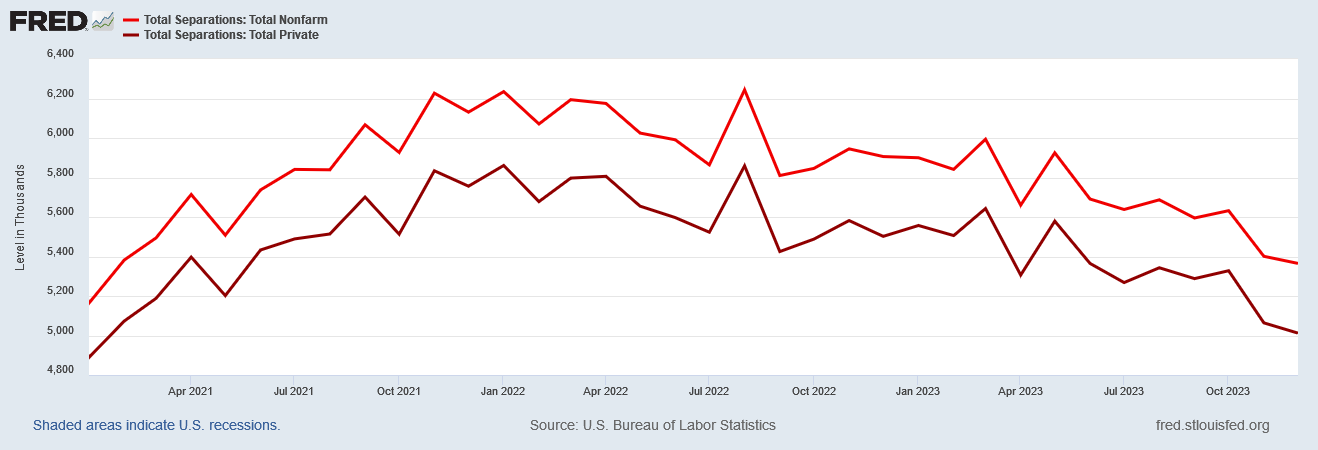

On the flip side of the labor coin, the separations data also continues to show growing weakness—weakness which has been there since early 2022.

Overall separations have been declining in the US.

However, that broad decline is not the complete story.

Within the separations data, we see that the bulk of the change is due to the decline in quits.

This decline is also significant, because the other major category of separations, layoffs and discharges, has been increasing since early 2022.

Voluntary separations are on the decline—and have been—but involuntary separations are rising.

Layoffs are generally associated with economic duress, not economic prosperity. Quits signify the exact opposite—when voluntary separations are rising, the perception is that the economy overall is healthy, and there is an abundance of job opportunity.

As with the decline in hiring, the December non-farm quits number was the first time since early 2021 that quits registered below pre-pandemic levels.

While workers have been increasingly reluctant to leave their job for most of the past two years, December was the month when that reluctance finally exceeded pre-pandemic levels.

A return to pre-pandemic levels of worker pessimism is hardly good news for the economy overall.

In one sense, the December JOLTS Report is not “news”, as it is largely a continuation of what was observable in the November report.

Shrinking hiring and softening labor markets are not signs of a “soft landing” for this or any other economy. They are signs of a recession.

Declining labor force participation is not a sign of a “soft landing” for this or any other economy. It is a sign of a recession.

These are signs that workers who lose their jobs are more and more often simply choosing to exit the labor force altogether. These are signs that there are far fewer actual jobs to be had than the distorted job openings data suggests. These are signs that the much ballyhooed “success” both of the Federal Reserve’s strategy on inflation and the current regime’s economic policies have delivered a stagnating, contracting economy that remains mired in the recession that it has endured since 2022.

The November JOLTS report was not “good news”, and the December JOLTS report is likewise not “good news”.

However, this continuation in December of November’s trends is not a case of “no news is good news.” The December report is a continuation of bad trends and bad news. The December JOLTS report is but a further indicator that neither the economy nor the labor market in the United States are particularly healthy, and that they both have been doing far worse than Wall Street wants to admit, and for far longer.

What I’m seeing , as you’ve noted I think, is the government is doing a lot of hiring but private sector is laying off. Did you see UPS laid off 12,000 yesterday? That’s a bad sign. Our economy is being propped up by tax credits.

Two years! This data shows that the job market, overall, has been worsening consistently for the past two years. All kinds of questions come to mind: Will the cumulative effect of this result in an economic big drop off soon? Does it indicate an underlying economic weakness, of declining manufacturing, and worsening readiness of the workforce in terms of education and training? Sure, Boomers are retiring, but some are leaving the job market because of personal problems such as drug addiction, right? Are the Overlords in power truly this clueless?

I imagine your answer is “yes, to all of the above”, (although with some qualifiers).

I could see a cultural shock coming, of war or depression jolting the American culture into realizing that we simply MUST get our act together. Stop the whining culture of being offended by everything and get serious about self-improvement. I sure hope so!