The corporate media narrative is that inflation is down, job creation is up, and the economy is doing well.

Except…not even the “experts” seem to believe that.

If the economy is doing well, why is Jay Powell and the Fed hesitant to trim the federal funds rate back towards what they feel is the “neutral” rate of interest?

Addressing a business conference at Stanford University, Powell touted progress in the fight to cool price increases while acknowledging that such headway had stalled in recent months.

“On inflation, it’s too soon to say whether the recent readings represent more than just a bump,” Powell said.

While inflation might be falling according to the BLS headline number, subindices such as food are still showing the effects of elevated inflation.

Grocery prices have risen 21% in the last three years, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Andrea Leo owns Sun Market grocery store in Denver, Coloradom and says she does her best to keep food prices low, so customers will continue to come in.

Yet when confronted with consumer confidence data indicating that inflation has gotten worse not better, what does corporate media do? Blames consumers.

In The Wall Street Journal’s latest poll of swing states, 74% of respondents said inflation has moved in the wrong direction in the past year.

This assessment, which holds across all seven states, is startling, sobering—and simply not true. I’m not stating an opinion. This isn’t something on which reasonable people can disagree. If hard economic data count for anything, we can say unambiguously that inflation has moved in the right direction in the past year.

The Wall Street Journal headline for the above quote says much more than the Wall Street Journal I suspect realizes.

Reality check: the consumer, like the metaphorical customer in the hoary cliche, is always right. The “experts” would do well to understand that and to stop missing that essential point.

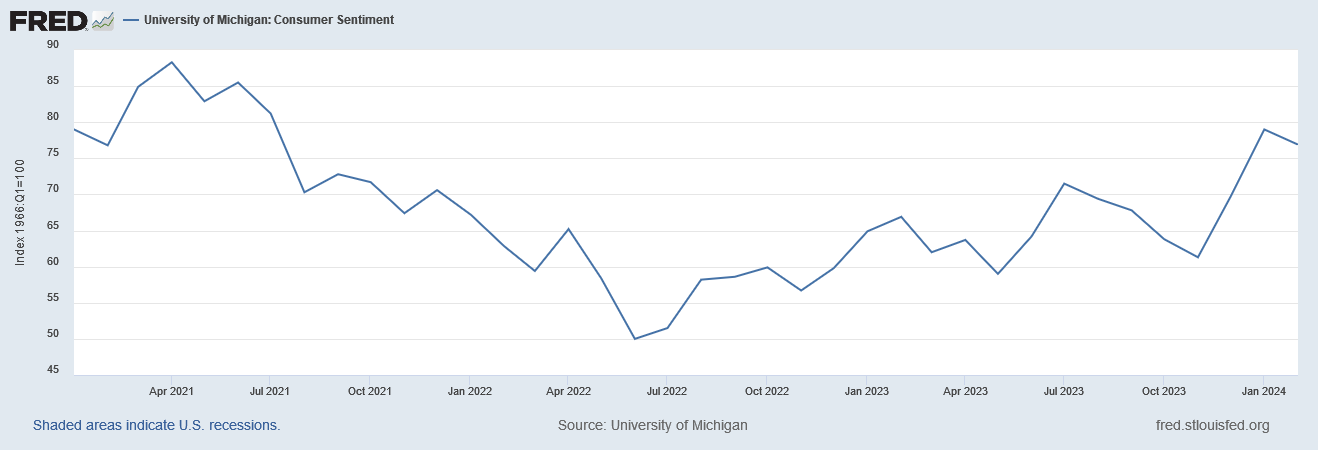

The fundamental disconnect between consumer confidence and the “experts” rosy assessments of the economy begins with the realization that consumer confidence has been substantially negative for quite some time, meaning any incremental improvement ultimately is just being a little less negative.

This is immediately apparent when we look at the state of consumer confidence from the start of the Trump administration in 2017.

Even though consumer confidence has been trending up from its nadir in July of 2022, it still remains well below where it was just prior to the Pandemic Panic Recession.

If we zoom in on Joe Biden’s Reign of Error, we see that consumer confidence has actually fallen since January 2021, that the upward trend from July 2022 onward has not been sufficient to recover all the confidence lost during the first 18 months of the Biden Regime.

Despite many ups and downs, the first three years of the Trump administration saw consumer confidence actually move up slightly.

When we look at inflation’s trajectory from the start of the Trump administration, it is not hard to see the reason for the variance in consumer confidence between the Trump era and the Biden era.

Despite a downward trend in inflation over the past 20 months, inflation is still higher than it was ever during the Trump era.

That reality almost certainly goes a long way towards explaining the negative consumer confidence levels. Inflation might be heading in the right direction but it veered off in such a substantially wrong direction that there is still a lot of course correction yet to do.

In a new working paper1 from the National Bureau of Economic Reasearch, a quartet of economists including former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers propose an explanation as to why consumer sentiments remain so decidedly negative. Their conclusion is that inflation metrics today do not account for the cost of capital—for interest rates, in other words.

Unemployment is low and inflation is falling, but consumer sentiment remains depressed. This has confounded economists, who historically rely on these two variables to gauge how consumers feel about the economy. We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap. The cost of money is not currently included in traditional price indexes, indicating a disconnect between the measures favored by economists and the effective costs borne by consumers. We show that the lows in US consumer sentiment that cannot be explained by unemployment and official inflation are strongly correlated with borrowing costs and consumer credit supply. Concerns over borrowing costs, which have historically tracked the cost of money, are at their highest levels since the Volcker-era. We then develop alternative measures of inflation that include borrowing costs and can account for almost three quarters of the gap in US consumer sentiment in 2023. Global evidence shows that consumer sentiment gaps across countries are also strongly correlated with changes in interest rates. Proposed U.S.-specific factors do not find much supportive evidence abroad.

Certainly there has been a sizable increase in the level of credit card debt in this country, an increase which began shortly after inflation began to rise in earnest in 2021.

It takes no great economic insight to see that the rise in credit card debt will make consumers more sensitive to the interest being charged on that debt. We should note also that credit card interest rates are one of the interest rates which track to the federal funds rate.

This is important because the far more publicized treasury yields and corporate bond yields have been increasingly disconnected from the federal funds rate, a phenomenon I have commented on several times since the Fed’s rate hike strategy began.

For all the fears and hand-wringing (some of which is justified) over the impact of rising interest rates on the banking industry, as well as other economic ramifications, the brutal truth of the Fed’s rate hike strategy is that its burdens have always landed more on consumers than anyone else. Main Street has paid the freight for the Fed’s strategy, not Wall Street.

Yet there is an additional dimension to the impacts of the Fed’s rate hike strategy, which the NBER Working Paper begins to touch upon. The “official” inflation rate is not an objective presentation of economic reality, but is itself an assessment of how prices are moving in both relative and absolute terms.

At the heart of the issue is a misconception that bedevils academics, journalists, and ordinary Americans: the idea that the official inflation rate is an objective number, impervious to human biases, much in the way that someone’s height or weight can be objectively measured with a ruler and a scale.

In fact, the formula used to calculate the inflation rate is subjective. It requires economists to make hundreds of judgment calls about how one assesses the overall trajectory of prices. What goods and services should be included in the “basket” of prices in the formula? How should those goods and services be weighted against each other? How do we account for the fact that poor people consume different things than rich people, or that people in different parts of the country may consume different things in different proportions? What is the best way to measure changes in the price of important things like housing?

As a consequence, different inflation measures yield different levels of inflation. We see this monthly in the difference between the data put out by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the CPI vs the PCEPI. If we look at private metrics such as the American Institute for Economic Research Everyday Price Index, we have yet another measure of inflation. Alternative economics site ShadowStats puts out yet another measure developed by economist John Williams, which seeks to recreate inflation calculations using the formulas used before 1980 and 1990.

Readers will recall I have commented before on the variation in inflation data based not only on the particular metric but also the region of the country one is examining.

However, even within the realm of “official” government data, we can see one very stark reason consumers are feeling the pinch at all.

Since 2021, wages have not kept pace with inflation.

When we look at the index of the CPI compared to the index of average weekly wages since the start of 2021, we see just how much more inflation has risen relative to wages.

This is where the corporate narrative takes liberties with the data, because while the claim that real incomes are rising hinges on only looking at the most recent data. If we move the index forward to when inflation peaked in this country, we see that incomes have risen since then more than inflation.

Yet if we move the index forward to the start of 2023, we see that incomes are just keeping pace with inflation.

Thus while it is “technically” true within the “official” government data that incomes are rising relative to inflation now, that rise does not do much to make up for the ground lost in 2021. Workers are still very much in a worse off position economically now than at the start of the Biden Regime, and the “official” government data proves it.

That lost of real income is almost certainly why credit card debt has risen dramatically in this country, and that loss of real income is almost certainly why consumers are particularly sensitive to credit card interest rates.

That loss of real income makes consumers more sensitive to mortgage rates.

That loss of real income makes consumers more sensitive to car loan interest rates

That loss of real income makes consumers more sensitive to bank loans of all kinds—many of which are assessed at or above the Prime Rate, which is also based on the federal funds rate.

Nor does it take a PhD in economics to understand that a loss of real income is going to sour the most optimistic person’s disposition. When we have less money and less purchasing power, we have less economic freedom. How can that not impact our happiness, and therefore measures of consumer sentiment and consumer confidence?

This is what the “experts” keep missing: inflation has hurt the average consumer. Inflation has hurt the average worker. Neither consumers nor workers have recovered from the damage done to wages and purchasing power in the 2021 aftermath of the Pandemic Panic Recession.

Main Street took it on the chin to pay for the government’s economic lunacies—for the lunatic lockdowns of 2020, for the ginormous expansion of the money supply, and for the Fed’s rate hike strategy. The data spells this out is stark detail—the “official” government data spells this out in stark detail.

Perhaps if the “experts” who know so much about that data would acknowledge that simple empirical objective reality about the data, they might have a better grasp on where consumer sentiments are regarding the economy, and why.

Bolhuis, Marijn and cramer, judd and Schulz, Karl Oskar and Summers, Larry, The Cost of Money is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly (February 2024). NBER Working Paper No. w32163, Available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w32163/w32163.pdf

I went to the grocery store today, people are pissed. I don't blame them.

I'm pissed too.

You are so very good at what you do, Peter. Your insights are accurate and brilliant. Thank you again.