The Russian Ruble: Riches Or Rubble?

Putin's Currency Woes Make "Victory" In Ukraine Ever Problematic

Is Vladimir Putin “winning” in Ukraine? Can Russia prevail in that war, or is the Russian state and Russian economy doomed to failure and ultimate collapse?

Those are very loaded questions, and as any brief survey of podcasters, corporate media outlets, and YouTube commentators will show, there are as many answers to those questions as there are podcasters, corporate media outlets, and YouTube commentators—and every single one of them is absolutely correct and has the real skinny on what’s “really happening” in Ukraine. Just ask them.

We do not know what the ultimate outcome will be in Ukraine. Wars are murky and messy affairs, and they are neither won nor lost until the shooting ultimately stops.

We do know, however, that Russia’s economy has taken some significant hits recently, enough to raise the possibility that Putin may have considerable incentive to let Donald Trump broker a peace arrangement with Ukraine, simply in order to forestall economic chaos and possible collapse.

As Trump’s ability to secure peace in Ukraine is likely to be an early opportunity for success or failure in his second term of office, it behooves us to look at what is happening on the home front in Russia.

What can the data tell us about the state of Russia’s economy?

The genesis of this article came about last month, when the Russian ruble went into a precipitous decline against the Chinese yuan.

The ruble had been in decline since August, but November was when things went almost into freefall, such that at one point the ruble was down on the year against the yuan by more than 20%.

This has major ramifications for Russia, as China has take Europe’s place as Russia’s principal trading partner in the wake of sanctions levied in response to the war in Ukraine. 2024 to date has been quite a growth year for Chinese exports to Russia.

China exported around 80 billion yuan worth of goods to Russia in the month of September, a 9% increase from the 73 billion yuan worth of goods it exported the prior month, according to Chinese customs data published on Tuesday. That's larger than the increase recorded over the last several months, with Chinese exports to Russia rising 3% in August and 1% in July.

In an ominous sign for Russia, however, Chinese imports from Russia have fallen.

China's imports from Russia, however, fell 4.3% last month from a year earlier, narrowing from the decline of 9.2% in September, as payment issues disrupted trade transactions.

In a talk with Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Rudenko last month, China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi reiterated China and Russia's strong relations, that were not affected by "changes in the international situation".

The driving force behind most of the payment hurdles dirsupting Sino-Russian commerce have actually been the increasingly stringent financial sanctions being levied over the summer by the US and the EU in efforts to disrupt Russia’s ability to purchase raw materials to sustain its war production.

In particular, the US targeted Chinese firms doing business with Russia.

The sanctions target third party firms and entities, including dozens of suppliers of electronics in China, as well as those in the Middle East, Africa, Europe and the Caribbean. The action stops short of imposing secondary sanctions on banks in China and other countries where Treasury has warned that dealings with Russian entities could cut institutions off from dollar access.

But the Treasury did say it was modifying the sanctions on previously targeted Russian banks, including VTB and Sberbank, to include branches and subsidiaries in China, India, Hong Kong, Kyrgyzstan and other locations.

Pressure came to a maximum when the US applied fresh sanctions to Gazprombank, the Russian banking concern that foreign countries use to process their payments when purchasing natural gas from Gazprom.

The move effectively kicks Gazprombank - one of Russia's largest banks - out of the U.S. banking system, bans their trade with Americans and freezes their U.S. assets.

Gazprombank is partially owned by Kremlin-owned gas company Gazprom (GAZP.MM). Since Russia's invasion in February 2022, Ukraine has been urging the U.S. to impose more sanctions on the bank, which receives payments for natural gas from Gazprom's customers in Europe.

The fresh sanctions come days after the Biden administration allowed Kyiv to use U.S. ATACMS missiles to strike Russian territory. On Tuesday, Ukraine fired the weapons, the longest range missiles Washington has supplied for such attacks on Russia, on the war's 1,000th day.

That these sanctions had an impact is immediately apparent just from the decline in the ruble against the Yuan.

While the ruble was in freefall against the yuan for about a day or so, it did manage to stablize right before thanksgiving, establishing a floor price against the yuan and even rebounding slightly.

As of this writing the ruble was holding steady at 1 ruble being worth 0.0670769 yuan.

Unsurprisingly, the ruble stabilized against the dollar as well (the yuan and the dollar frequently mirror each other when tracked against third party currencies).

After managing to remain above the rate of 100 rubles to the dollar since the war begin, the ruble has found a new stable threshold (as of this writing) against the dollar at 1 ruble to 0.00926072 dollars.

In an encouraging sign for Russia, this stability against the dollar has come even as the yuan has spent the week showing some increased volatility against the dollar.

While the ruble’s 16% decline on the year against the yuan (as of this writing) is a major setback for the Russian currency, the stabilization means the Russian economy at least is not getting any worse!

Arguably, this could be seen as something a win for Russia, because while the Russian economy has been taking a beating, Russian forces have been making headway in eastern Ukraine, taking a significant bit of territory around the city of Kurakhove during the month of November.

However, there are still problems within the Russian economy and merely stabilizing means they have not yet gone away—and may not go away.

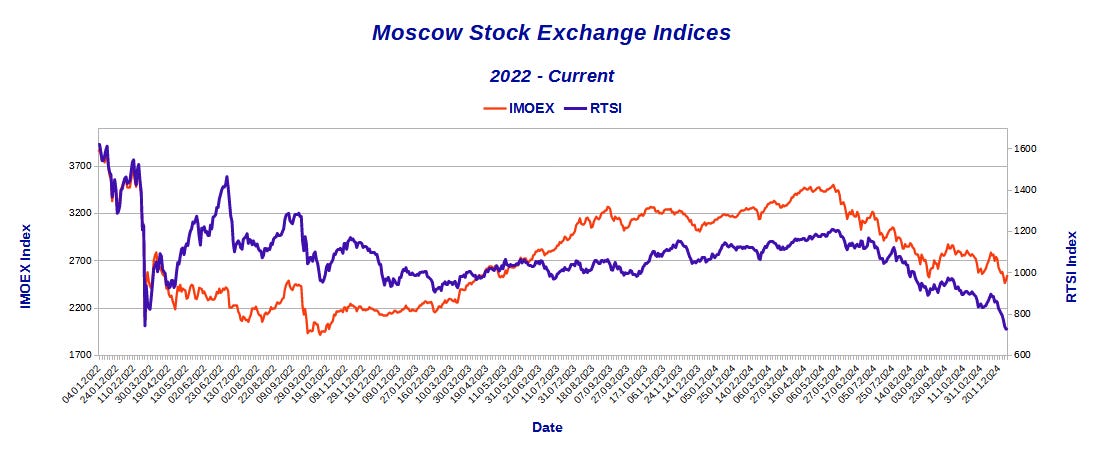

Aside from the currency crisis, the most notable outward sign of trouble for the Russian economy is that the Moscow Stock Exchange (MOEX) has declined largely as the ruble as declined since August.

Both the ruble-denominated IMOEX index and the dollar-denominated RTS Index are in deep “bear” territory, having declined more than 20%.

While a country’s economy is more than just its stock market, declines of this magnitude for Russian firms is a fairly dramatic illustration of the uncertainties at play in the Russian economy. There are very few scenarios where a decline in the stock market of this magnitude is not an indication of a brewing economic crisis.

More crucially, however, is the problem of inflation.

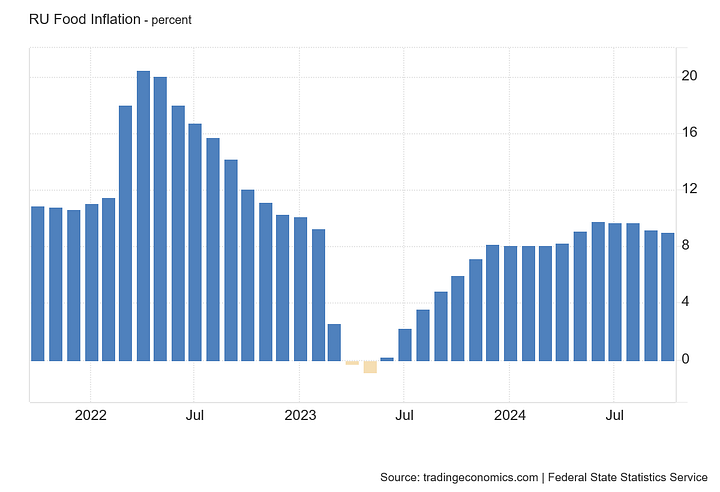

Theoretically, inflation is under control, as Russia’s official inflation rate is at 8.5%, and the official food price inflation rate is at 9%.

However, the prices for many foodstuffs have soared far higher than that in 2024.

The price of a block of butter has risen by 25.7% since December, according to the state statistics service.

Reuters reporters found shopping bills showed the price of a pack of "Brest-Litovsk" high-grade butter in Moscow has risen by 34% since the start of the year to 239.96 roubles ($2.47).

"The Armageddon with butter is escalating; we wouldn't be surprised if butter repeats last year's situation with eggs," economists on Russia's popular MMI Telegram channel warned, referring to an earlier spike in egg prices which alarmed consumers.

The steep price rise has prompted a spate of butter thefts at some supermarkets, according to Russian media, and some retailers have started putting individual blocks of butter inside plastic containers to deter shoplifting.

While prices do vary within any inflation metric, for the price of a staple such as butter to be that far outside the range of the “official” inflation rate invites suspicion that Rosstat—the Russian statistics bureau analogous to the BLS and BEA here in the United States—is getting a bit “creative” with the data. I certainly am quite willing to entertain such ideas when the BLS and BEA data here in the United States looks a little sketchy when it gets reported!

At a minimum, Russia is experiencing some significant price dislocations. One does not need a PhD in economics to realize that there are numerous warning signs indicating the Russian economy is heading into some very rough waters.

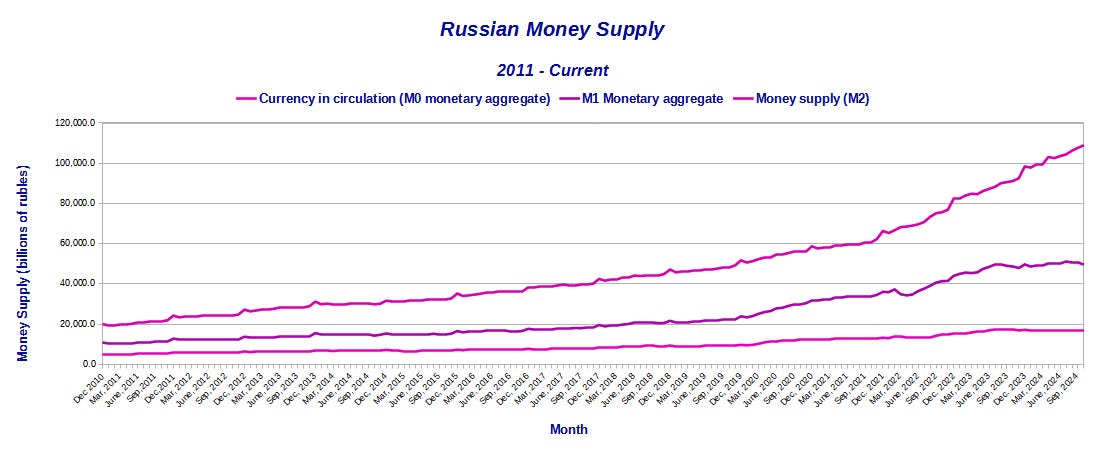

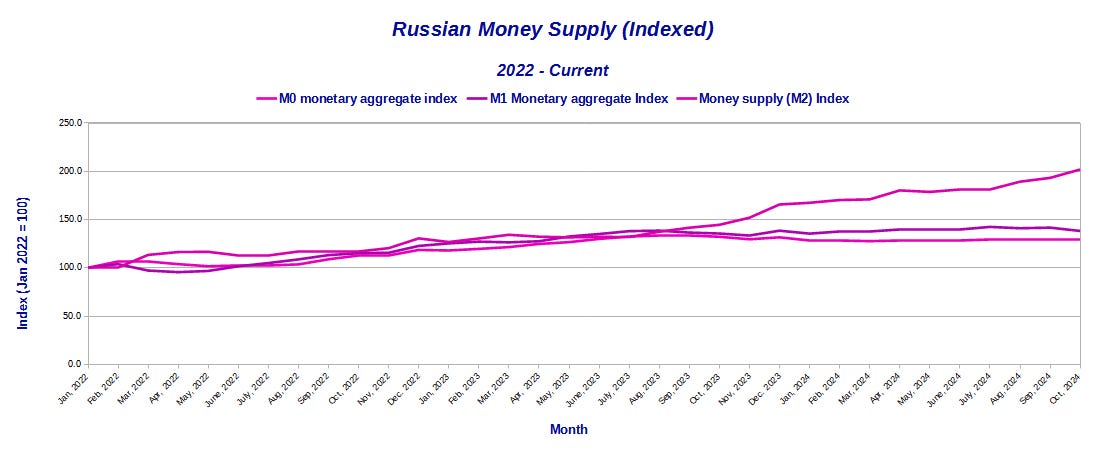

There is very little mystery as to what is driving up inflation in Russia: ultimately, it’s Putin’s war in Ukraine. More precisely, Russia having converted over to a wartime economy, and Putin printing rubles at an accelerated pace, is experiencing inflation in the fashion that most wartime economies have throughout history. This is the historical norm when the money supply is expanded rapidly, and Putin has been expanding the supply of rubles for quite some time, going back years.

If we index the money supply data from the Russian Central Bank (RCB), we can see just how much the money supply has grown.

The quantity of rubles in circulation has increased more than 347% since 2011, but the M1 money supply aggregate has increase 476% and the M2 aggregate by 564%.

A sign of the demands from Russia’s war machine, the pace of M2 increase rose again starting in 2023, even as the M1 and M0 metrics began to stabilize and flatten out.

By comparison, the Federal Reserve has been positively restrained with the US money supply since 2022.

This is Putin’s problem in a nutshell: how to prevent hyperinflation while continuing to print (and spend) rubles at ever increasing rates?

To be clear, the ruble at least for now has stabilized. Russia is not facing complete currency collapse, which means its economy will be able to soldier on for at least a little while longer.

However, The ruble has lost 16% of its value against the yuan in just a few short months—a tremendous devaluation by any measure.

Food prices are reflecting a level of inflation that more or less matches that rapid money supply growth.

The Moscow stock market is reflecting a drop in value that again seems proportionate to the loss of currency value, and the decline broadly matches when the ruble began its significant decline in August.

These are signs of real problems within the economy, and, absent a recovery in both the currency and the stock market, there is no reason to anticipate they are going away any time soon.

Yet Russia is hanging on, for now, economically speaking. Things are not on the brink of collapse, and Putin’s back does not appear to be against any wall. Obviously that would change if the currency declined much further, and if inflation spun out of control despite the RCB’s efforts to contain it.

We can also fairly state that, if circumstances persist as they are as of this writing, Putin’s capacity to “win” in Ukraine may prove to become increasingly elusive, as a deteriorating economy will make it that much more difficult for Russia to mount the final blow that would finally knock Ukraine out of the war.

Yet such challenges are far from saying that Putin is “losing” the war in Ukraine, or even that he is likely to lose. If Russia cannot deliver a knockout blow, then the outcome of the war quickly reduces to who is able to last the longest militarily and economically in the horrific war of attrition that has become Europe’s most brutal conflict since WW2.

Is Vladimir Putin “winning” in Ukraine? Ultimately, that depends on your definition of “winning”. Personally, unless Donald Trump is successful at getting the two sides to the negotiating table and crafting a lasting peace, I can’t see applying “winning” to the outcomes for either side. Neither Russia nor Ukraine are likely to emerge from this war in good shape by any measure.

Merely being the last one standing in a fight is just not enough to qualify as “victory” in my book.

Yes. To the engineering mind it’s a case of ‘too many variables, too many unknowns’ - can’t make a mathematical model here. If we all thought that the election year of 2024 was interesting, that’s going to look like a laid-back picnic compared to 2025!

Another great topic, Peter! Thank you, as always.

I’m hoping you can help us grasp the ‘high finance’ aspects of this situation. If Russia’s currency and economy are tanking, and China’s economy is tanking, and now Iran’s regime may topple as Syria’s Assad is (possibly) being deposed, what happens to international finances? Does the dollar automatically strengthen, because it is the relatively most stable currency? Or does America’s economy, or stock market, or dollar, get dragged down by the troubles of everyone else - especially in terms of hyperinflation? Is it all way too volatile to predict any outcome? Is it chiefly a matter of relative rates of tanking - which economy, how quickly, and how severely? I’m seeing it as a jumble that is too complicated for anyone to be able to predict any outcomes, but if there’s a mind that could see a clear pattern, it would be yours, Peter.