Wall Street Thinks The Banking Crisis Is Over. Guess Again.

We're Still In The First Act

The large “globally systemically important banks”1—the ones that are so big that any hint of weakness on their part requires massive government intervention funded by taxpayer dollars—called “time” on the 2023 banking crisis, and congratulated themselves for having survived yet another display of their monetary madness and financial fecklessness.

“I think as a systemic risk, it’s over,” UBS Chairman Colm Kelleher said at The Wall Street Journal CEO Council Summit in London.

“What’s not been solved yet is what is the funding model that will work going forward.”

Barclays Chief Executive Officer C.S. Venkatakrishnan added that the acute crisis has passed but that many banks will be forced to change their business models—including possibly by curtailing lending. “I think the phase of initial discovery is over and I think there’s going to be a little bit of a longer-term discovery and adjustment,” he said.

Okay, I admit…I might be paraphrasing what they said just a tad.

The alternative is to take them seriously, which is an utter absurdity.

No, the banking crisis is not over—not even close. Nor will it end soon because bankers really and truly have nary a clue how to manage money. Particularly depositors’ money.

To appreciate just how colossally clueless bankers have been about their own industry, consider how the bankers’ paper of record, The Wall Street Journal, frames the crisis.

Rapid inflation has led the Federal Reserve, Bank of England and other central banks to quickly raise interest rates since early 2022 to cool off the economy. That in turn has devalued government bonds that carry low, fixed interest rates—slashing the value of assets on many banks’ balance sheets.

In the case of the Federal Reserve, “quickly” equates to “over the past fourteen months”, as their first push on the federal funds rate came in March of 2022.

More importantly, the Federal Reserve’s first action on the federal funds rate came at least a month after market interest rates began trending upward without Fed action.

A full year before the banking crisis, the interest rates that would catalyze the crisis began rising, and yet no banker figured there would be a problem.

Seriously.

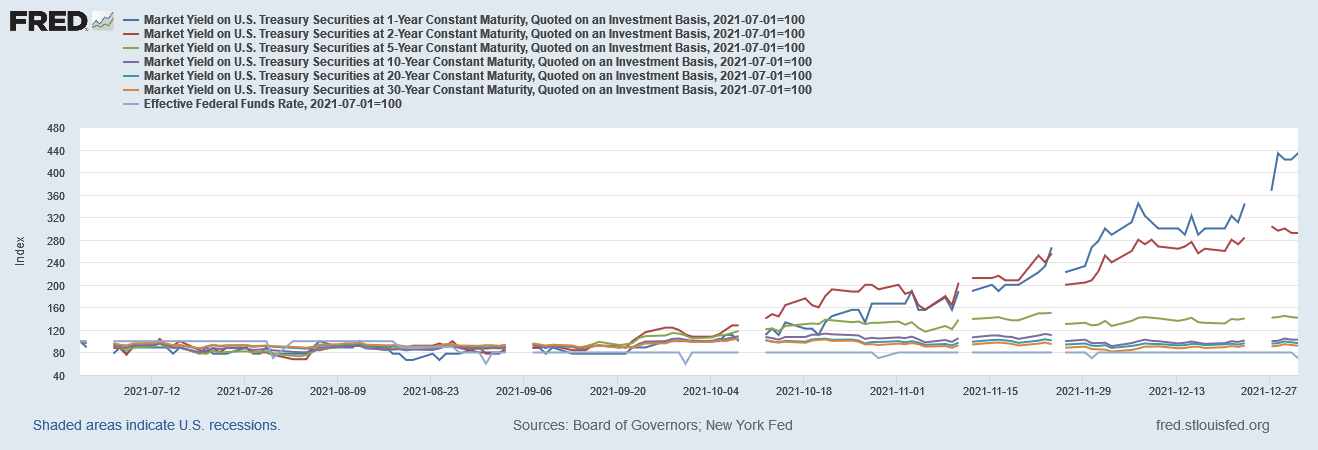

This is not idle speculation. The historical data is quite clear on this point2.

By the end of December, 2021, short term interest rates had risen to as much as four times their July 1, 2021 levels—a full 10 weeks before the Fed’s first rate hike. Long term yields had risen as well.

Long before the Federal Reserve began raising the federal funds rate, Wall Street was already pushing up Treasury yields. Yet somehow none of the realized the consequences of this paradigm shift until just this past March, when the financial tides receded and all the large bankers were found to be swimming naked.

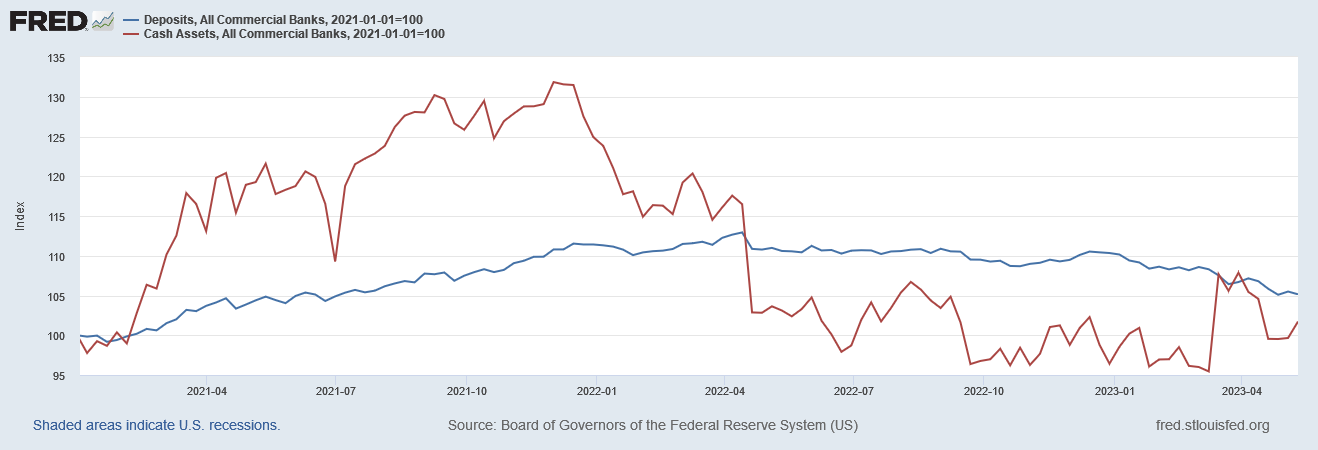

Having failed to grasp that a market environment of rising interest rates would shred the market value of low-yield assets (such as Treasuries bought before the rate hikes began), bankers also last year failed to comprehend the financial problem inherent in losing deposits—and banks began hemorrhaging deposits roughly a month after the Fed started raising the federal funds rate. From April 13, 2022, onward, and for the only time within the extent of the available data, the banking system lost nearly 10% of total deposits.

With the banking system still losing deposits, why would any banker believe the crisis was over?

Moreover, there have been numerous other canaries in the bankers’ coal mine.

In late December, 2021, banks also started seeing significant declines in their cash assets.

As the trend in deposits began reaching its peak in early 2022, banks also started losing cash—and would see a steep drop in cash at the same time deposits themselves began to decline.

Nor is there any great mystery as to why banks have been losing both cash and deposits—depositors are chasing yield, moving their idle cash from low-yield bank savings accounts to higher yield money market funds.

Large banks are bleeding deposits primarily because bank deposits are no longer providing enough yield for wealthy customers in particular to justify keeping their deposits there—not when money market funds are offering interest rates more in line with current treasury yields, as a quick survey of money funds offered by Charles Schwab Asset Management confirms.

A quick review of money market yields shows that they are still offering better yields by far.

The crux of the problem—deposit outflows—is still ongoing and the incentives for pulling money out of a bank have only increased.

Indeed, a quick survey of current bank data shows that large banks have not fully addressed the imbalance between cash assets and deposits.

While most banks reversed the downward trend in their cash assets following the March fracas over Silicon Valley Bank, large banks are on a glide path to seeing the cash problem return.

While all banks shored up their cash positions after the SVB collapse, large banks have not worked to sustain that growth, and are allowing their cash buffers to dwindle again.

Smaller institutions, it should be noted, are having more success.

Another red flag that was overlooked was that loan activity was not moderated when deposit levels started to decline.

Deposits are the basis on which a bank can make loans. When deposits began to decline, bankers failed to adapt their loan practices accordingly, so that an increasing amount of loans rested on a decreasing amount of deposits. This is a recipe for instability.

Moreover, despite the failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank of New York, and First Republic Bank, bankers have still not resolved the growing imbalance.

Despite a year to recognize an adapt to the changing interest rate and deposit environment, bankers have still not moderated loan activity to keep it trending in line with deposits.

With cash assets relative to deposits declining, with loans relative to deposits increasing, and with deposits themselves decreasing, there can be no question but that a future liquidity crisis is brewing. At some point—we cannot say precisely when—at least one bank is going to be caught betwixt and between with depositors wanting their money on the one hand and an unforgiving market forcing them to take big losses on their loan assets on the other. So long as these trends continue in this fashion such a liquidity crisis is guaranteed to happen—it mathematically must happen.

Nor should anyone be surprised at this. It has been obvious since last September at the latest that the rising interest rate environment being encouraged by the Federal Reserve was going to create liquidity crises.

The concern within financial markets today is that, as the Fed tightens the money supply to control inflation, there will not be enough dollars at crucial points to satisfy dollar liquidity demands. In other words, there is a perceived risk on Wall Street that, as the Fed reduces the overall supply of money, that there will not be sufficient dollars available to participants in various asset transactions to allow those transactions to be completed.

Bank runs are a pure expression of this phenomenon—if enough depositors pull money from a bank, the bank will run out of cash before it satisfies all depositor demands, and the bank fails.

We have seen this play out at three banks, thus far, and counting.

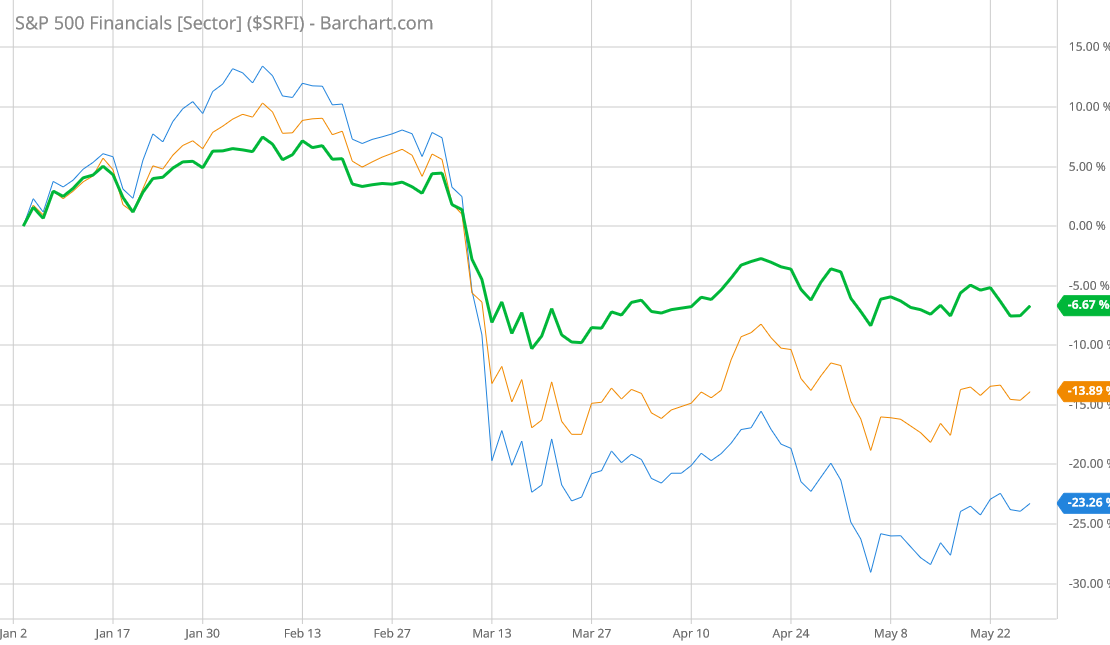

For its part, Wall Street still doesn’t get it. While bank stocks are still down on the year, the bank indices have largely stabilized, suggesting that investors are persuaded that banks have no more interest rate skeletons rattling around in the asset closet.

It may be that the particular banks to fail will not be the likely suspects from a few weeks ago. Up until this past week, PacWest was perhaps the leading candidate for the next banking domino to fall, but it may have succeeded in selling off enough assets to be able to ride out the paradigm shift.

Roc360, a real-estate lending firm, will buy the bank’s Civic Financial Services unit, which specializes in lending money to landlords and investors who buy homes to fix them up for resale. Maksim Stavinsky, Roc360’s co-founder and president, said the deal closed Tuesday but didn’t provide terms.

Yet if it will not be PacWest that falls, it will be another. Even if all banks with underwater assets were motivated to unload them, dumping any tranche of assets on the market all at once will drive the price down even further, complicating a struggling bank’s liquidity and solvency issues.

At some point, there will be a bank caught on the wrong side of an asset fire sale, caught between the fire sale and the bank run, and will have to be taken over by the FDIC. At some point, that bank failure will spook depositors even more and catalyze a repeat scenario. At some point this could turn into a generalized bank run, and we get to replay the events of early March all over again.

Banks cannot exist without deposits.

Banks cannot profit without making loans.

Without deposits, banks cannot make loans.

As a direct consequence of these basic principles, any shift in the financial environment that makes deposits more dear and loans more challenging (both to originate and to service) is going to stretch some banks to the limit. When enough banks are stretched to the limit some banks will break and fall.

The banking crisis is not over, because the forces making deposits more dear and loans more challenging have not abated. If the Fed hikes in June, those forces are only going to get stronger in the near term.

Until these forces abate and the interest rate environment stabilizes once more, we are all simply waiting for the next bank to be caught short and fail.

Financial Stability Board. 2022 List of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs). 21 Nov. 2022, https://www.fsb.org/2022/11/2022-list-of-global-systemically-important-banks-g-sibs/.

Most of the graphs are indexed values to a particular baseline date. This is done to illustrate the converging trends that occur even though the data sets themselves are of varying sizes—i.e., deposits have always amount to several times the cash assets a bank has on the balance sheet, making the absolute portrayal of the data unclear. Using indexed data keeps the trends and relative magnitudes of change intact while providing a common basis for comparing the data sets.

Yup.👏👏👏👏 couldnt agree more.

Im wondering or translate would like a closer look at INGs underwaters. Black rock and Vangaurd both have invested there. It would be interesting to trace the individual banks investors and see if there are any interesting patterns, especially on which banks may be changing their banking habits and which ones are slower. BTJMO