Longtime readers of this Substack will know that I routinely use global oil prices as a weather gauge for the global economy, and even for the state of global geopolitical tensions (such as the recent events in the Middle East surrounding Iran and the Houthis).

Despite ongoing conflict throughout the Middle East—despite continued attacks on Red Sea shipping, and continued drone attacks by Iran’s other Middle Eastern proxy militias—the global economy just does not possess the economic robustness needed for any efforts by Iran (or Saudi Arabia and Russia) to push oil prices up.

If anything, the lack of sustained energy price rises at a time of rising Middle East tensions underscores the extent of global economic weakness. If a constant looming threat of a Middle Eastern war can at most produce only transitory short-term price rises in energy, with the longer trend continuing to be that of pricing decline, we are forced to conclude that the global economy is in a far more parlous state, and has been that way for far longer, than many corporate media narratives have been comfortable admitting.

A global recession is unfolding, and has been for quite some time. Iran’s seeming inability to push oil prices up for any appreciable length of time, coupled with similar Russian and Saudi impotence despite their ongoing production cuts, is a loud and clear alarm klaxon that the global recession is getting deeper, and is likely to remain deeper for far longer than anyone realizes.

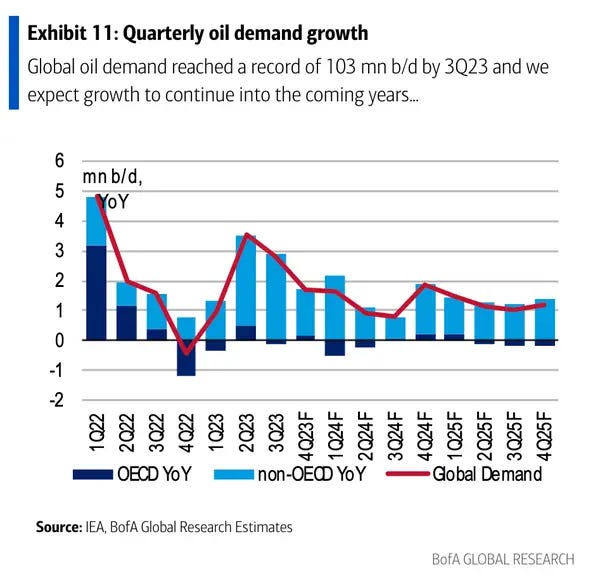

Oil market analysts offer some confirmation of this approach with assessments such as Bank of America’s recent take that global oil demand growth has most likely peaked.

Oil demand will still increase in the coming years, but thanks to things like improving technology and the switch to alternative fuel sources, the rate of growth has likely peaked, Bank of America said in a note this week.

Analysts led by commodity strategist Francisco Blanch forecasted that global oil demand should increase at a slower pace leading up to 2030 following the sharp rebound from pandemic lows.

Views that oil demand (or at least oil demand growth) is softening certainly dovetail with the view of a global economy that is softening and even contracting in some sectors.

Yet this leaves a recurring question: what are oil prices telling us about the state of the world today? Is the global economy getting stronger or weaker? Are geopolitical tensions rising or falling?

Let us look at what the data can tell us.

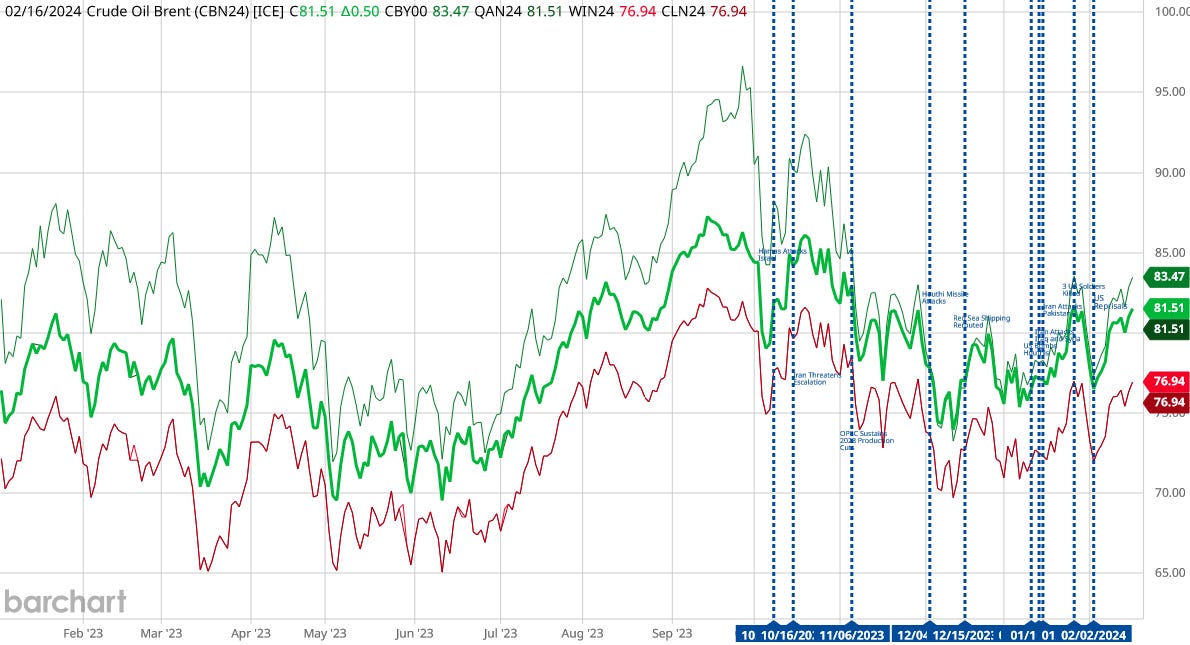

When we look at oil prices over time, the first striking thing we see is that oil prices today are at roughly the same level they were just prior to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February, 2022.

While the spot price for Brent Crude was highly volatile in 2022, futures contracts were far more moderated in their pricing. One takeaway from such variance between spot and futures prices is that commodities markets were being heavily influenced by emotion and impulsivity in 2022.

Yet even at that, we should also note that, by 2023, much of the volatility in spot oil prices subsided, and the spot prices converged on the futures prices to a large degree.

Whether we look at the spot price or at the futures price, throughout 2023 we see that oil prices largely moved downward during the first half of 2023, began to move up in the late summer. Most likely this would be due to Russian and Saudi production cuts starting to take effect.

Yet even production cuts only proved somewhat effective at pushing up oil prices in 2023, not succeeding in pushing futures prices beyond around $87/bbl, from which oil prices broadly trended down during the remainder of 2023. What might be arguably more important is that, from November onward, spot prices were very close to futures prices, even after the eruption of the Israeli-Hamas war which has been the catalyst for rising tensions throughout the Middle East. After an initial burst of volatility following the October 7th attacks, spot prices have remained close to futures prices—reiterating a thesis I have advanced more than once on this Substack, which is that oil traders do not see a wider Middle Eastern conflict arising out of current events.

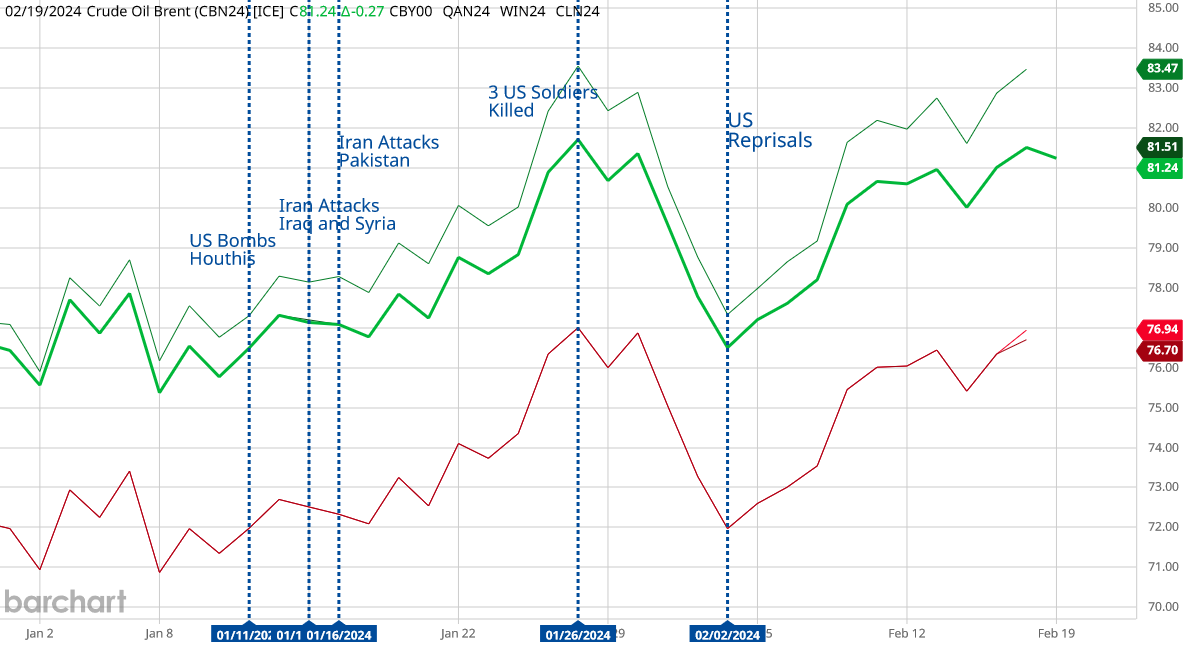

If we look at the oil price data year to date in 2024, we see that the spot price is still not substantially more volatile than the futures pricing.

Even the US reprisal strikes against the Houthis for their missile mischief in the Red Sea did not spark a surge of spot price volatility. More intriguingly, in the days surrounding Iran’s own air and missile strikes in Iraq, Syria, and Pakistan, oil prices declined in both the spot and futures markets.

We should note that oil prices had been broadly trending up before the US reprisal attacks began, roughly in line with when shipping firms began rerouting away from the Red Sea and the Suez Canal to avoid Houthi missiles.

As I noted at the time, the upward price pressures apparently originating from the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea—which arguably are at Iran’s instigation and certainly with Iran’s backing—while not negligible were also insufficient to replicate the price rises from the late summer period, suggesting that oil traders were still not pricing in much likelihood of a larger Middle Eastern conflict at the end of 2023.

Applying a Great Power lens to the Middle East, it is not irrational to presume Iran has a hand in events currently unfolding. However, as already stated, looking at the price of oil, if Iran is attempting to manipulate the price of oil through an expansion of the Israeli-Hamas war, Iran is clearly not having much luck. Even if Iran is not directly focused on oil prices, falling crude prices still imply that Iran is not seen as having any success expanding the Israeli-Hamas war.

Two months on from this, and the data arguably has not changed much in that regard. While oil prices have risen since the US struck targets in Iraq and Syria in retaliation for the deaths of 3 US servicemen in Jordan, they are still slightly lower than when those three deaths occurred.

Oil traders appear to be growing more concerned over tensions in the Middle East, but they also seem to be relatively conservative in that concern. We certainly have not seen any of the spot volatility spikes that characterized the weeks and months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

It is also worth noting that natural gas prices were similarly more volatile in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but since late December of 2022, natural gas prices have fallen tremendously.

Since January 2022, oil prices have risen roughly 20%, with all of that price increase coming in early 2022 during the initial period of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Absent Russian and Saudi production cuts, the trend from the summer of 2022 onward in was broadly downward, and even the production cuts failed to achieve the June 2022 peak in oil prices.

During this same time period, natural gas prices have fallen by more than 50%. Saudi production cuts and the onset of the Israeli-Hamas war have arguably served to stabilize oil prices within a $10/bbl trading band for Brent crude at between $75/bbl and $85/bbl, but no such stabilization force has been seen in natural gas prices, with the result being a veritable collapse in natural gas prices.

Some of this collapse in natural gas prices may be the result of the economic fallout from the surge in natural gas prices in 2022, particularly in Europe.

With Europe having been flirting with a measure of deindustrialization beginning in 2022, that level of economic decline we would expect to see reflected in declining natural gas prices.

This extreme decline in natural gas prices—a decline that has been far more pronounced in Europe than in the US—suggests is that deindustrialization may still be happening to some degree, in Europe especially.

Natural gas prices are reflecting a weakened global economy, just as oil prices have been, but without the buffering factors of production cuts to mitigate the price decline. Nowhere in global energy markets are there signs of significant economic expansion and growth.

Some of this apparent weakness in the global economy may be the result of a shift away from oil broadly, which certainly contributes to BoFA’s analysis that oil demand growth is peaking.

Specifically, what BofA is forecasting is a leveling out of demand growth for oil, which has been trending down since the second quarter of 2023.

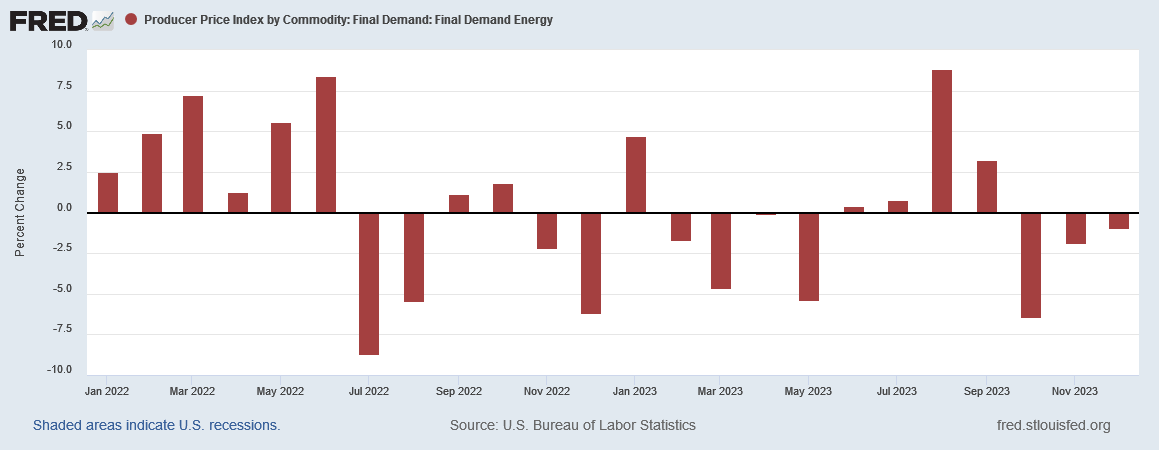

However, if a shift away from oil were the primary factor in energy prices not showing more upward response to global events, we should expect to see a different price behavior in the broader category of energy within US producer prices. However, we are seeing the same deflationary behavior for energy across the board.

If we look at factory gate prices for energy here in the US, we see that even at that level, energy prices have been deteriorating—which means the economies that depend on energy production have been coming under greater stress.

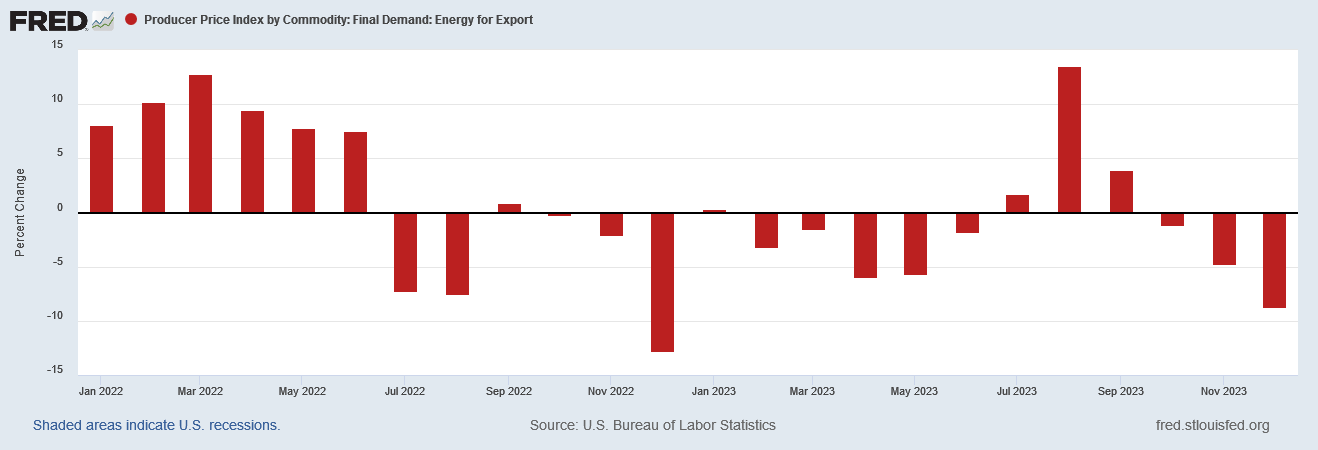

The case for a weakening global economy gets stronger when we consider that, here in the US, factory gate prices for energy produce for export have been declining.

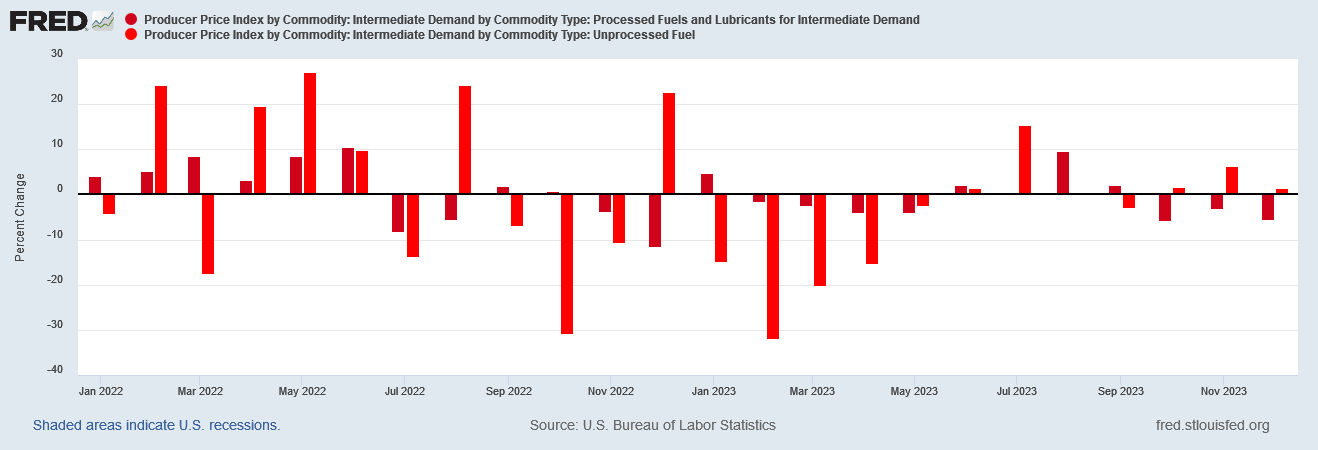

Adding to that case is the reality of declining prices for refined products—fuels and lubricants—which would not be part of a broad shift away from fossil fuels.

The greatest weakness in factory gate prices for fuels and lubricants is among the processed fuels and lubricants, not the unprocessed fuels. The greater the degree of refining involved in the energy product, the greater the deflation presented at the end of 2023..

Demand growth is slowing—which is a precursor to demand itself receding in absolute terms, if the trend continues.

Producer prices for energy are declining, and have been for months, with only occasional fluctuations to the upside. Producer prices for refined products are declining as well, including among those products for which non-oil-based substitutes are not readily available.

Commodity prices are not showing much sustained upward price pressure, even with rising tensions and increasing conflict in the Middle East.

Such trends give weight and credibility to the BofA assessment that demand growth is peaking. Certainly there is no serious pressure being seen from the demand side to push oil and energy prices higher.

Additional confirmation of this comes from Rystad Energy, which sees Indian demand for oil tapering off in 2024, after a surge in demand during the past two years.

Oil demand growth in the key Asian market of India is set to slow next year as the spurt in consumption that followed the pandemic fades, echoing a slowdown in China and presenting a fresh headwind for prices.

Consumption will expand 150,000 barrels a day in 2024, down from about 290,000 barrels a day from 2021 to 2023, according to Rystad Energy Head of Oil Trading Mukesh Sahdev. The drop will return growth near the pace seen from 2011 to 2019, he said. The International Energy Agency, meanwhile, sees growth halving to 100,000 barrels a day, according to its November report.

While there remain numerous prognostications of an eventual shift away from oil overall, the present reality remains that current pricing patterns have less to do with a greening of the global economy and more to do with a contraction in the global economy.

What we are seeing in oil prices is that, if Russia and Saudi Arabia had not initiated production cuts in 2023, and if Hamas had not attacked Israel in October of 2023, oil prices would have fallen in much the same fashion as natural gas prices. The percentage decline might not have been as great in oil as it was in natural gas, just as the percentage rise in natural gas was greater than it was in oil in 2022, but the downward trend in early 2023 confirms that global energy markets were softening, and only the production cuts acted to have any real stabilizing influence on them.

Simply put, global energy demand is simply not meeting the expectations that keep being placed on it by narratives of global economic growth, or even regional narratives of economic growth. If global economic growth is not producing the expected demands on energy, the reasonable conclusion is that global economic growth itself has not been as great as expected.

Even in year to date energy pricing, while we see some upward price pressure in oil prices, we are not seeing any such trend in natural gas, nor are we seeing any great increase in spot price volatility. This indicates that the upward price movements that have kicked off 2024 are almost entirely due to rising US involvement with the Houthis and their Red Sea missile attacks, and Iran’s multiple proxy militia groups in Iraq and Syria. We cannot reasonably point to any of that upward trend coming from economic growth.

An increase in economic growth would, at a minimum, produce greater volatility in spot oil prices, and we just are not seeing that.

At the same time, a lack of spot price volatility also suggests that oil traders are not supremely worried about the events in the Middle East which are slowly pushing oil prices up at the moment. We are seeing none of the indications of hysteria which presented in 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine. Increasing US engagement in the Middle East is naturally a cause for increasing concern, but oil traders do not see events spiraling out of control in the Middle East, at least not yet.

What are oil prices telling us about the state of the world today?

They are telling us that World War 3 is not quite around the corner. They are telling us that Iran is not even the regional hegemon it wants to be. They are telling us that Russia and Saudi Arabia have less control over oil prices than they would like.

And they are telling us that the global economy is still slowly going to Hell in a handbasket.

It was the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 that left me feeling unsure of my knowledge regarding high finance. Something called ‘collateral debt obligations’ (CDOs) torpedoed the entire financial system, and I had never even heard of them! During my entire life, I have read widely - I consistently read between 65 and 150 nonfiction books each year- yet I have never seen a reference anywhere to such a financial instrument. The Crisis left me feeling,” What ELSE don’t I know about?”. Very unsettling.

So, Peter, if you hear about other financial complexities or unstable instruments, you know I’d love to hear your thoughts about them...

Excellence in putting all the pieces together,Peter. Thank you, as always.

Last summer I watched a video by Dr. Chris Martenson explaining the convoluted interdependence of trillions of dollars in derivatives. He predicted that these derivatives would ultimately collapse, triggering economic disaster. So my question is, (if you’re interested in commenting): is there a level of demand in energy at which you see a ‘triggering’ of this sort of global economic collapse? That is, if energy prices decline by 10, 20, or 40 %, would you expect this triggering to occur? Or is there not enough correlation between derivatives and energy prices/demand to postulate an effect?