According to the US Commerce Department, retail sales edged down in October, the first decline in the seasonally adjusted data in seven months.

Advance estimates of U.S. retail and food services sales for October 2023, adjusted for seasonal variation and holiday and trading-day differences, but not for price changes, were $705.0 billion, down 0.1 percent (±0.5 percent)* from the previous month, and up 2.5 percent (±0.7 percent) above October 2022. Total sales for the August 2023 through October 2023 period were up 3.1 percent (±0.4 percent) from the same period a year ago. The August 2023 to September 2023 percent change was revised from up 0.7 percent (±0.5 percent) to up 0.9 percent (±0.2 percent).

The reported decline was actually less than had been projected, muddling any signal to be found in the data.

Retail sales, a measure of how much consumers spent on a number of everyday goods including cars, food and gasoline, fell 0.1% in October, the Commerce Department said Wednesday. That is above the 0.3% decline projected by Refinitiv economists but below the revised 0.9% gain recorded in September.

The decline in retail sales comes at a moment when multiple indicators are signalling declining demand throughout the economy. Given that the sales data is seasonally adjusted but not adjusted for inflation, the possibility that the decline is yet another such signal cannot be fully discounted, although a single month’s data is insufficient to reach that conclusion on its own.

That the sales data could very well be yet another indicator of demand destruction in the economy, we are forced to ponder comments made recently by Cleveland Federal Reserve President Loretta Mester, and ask “what does she want?”

“We’re making progress on inflation, discernible progress. We need to see more of that,” Mester told CNBC’s Steve Liesman during an interview on “The Exchange.” “We’re going to have to see much more evidence that inflation is on that timely path back to 2%. But we do have really good evidence that it has made progress and now it’s just, is it continuing?”

With mortgage interest rates in retreat, Treasury yields trending down, all amid a Fed policy of balance sheet and money supply reduction—exactly opposite what a shrinking money supply and Fed balance sheet should cause—how exactly does this constitute merely “progress” on inflation?

What signals does Loretta Mester wish to see before she would champion a shift in Fed policy? Does she even know? Is such a shift even advisable?

There is a certain sublime irony in Mester’s stated position on where the Fed’s monetary policy should be. While reiterating the Fed’s mandate to pursue maximum employment and price stability, she somehow equates that to the Federal Reserve maintaining a high degree of policy flexibility, responding to shifts in economic data as they become apparent.

Loretta Mester, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, highlighted the ongoing battle against inflation in her remarks at the Financial Stability Conference today. She acknowledged that despite maintaining interest rates at their highest level in over two decades for two consecutive meetings, a return to the Fed's 2% inflation target would require time.

Mester emphasized the importance of flexibility in monetary policy as the Federal Reserve navigates evolving economic conditions and potential risks to its dual mandate, which includes achieving maximum employment and price stability. The Fed is set to review its policy approach at the upcoming December meeting, considering these uncertainties.

There is a paradox in such a stance, because such a hyper-responsive and “flexible” monetary policy cannot possibly provide either maximum employment or price stability. The inevitable lags between the implementation of monetary policy and the emergence of new shifts and trends within various economic data sets by itself makes the use of monetary policy as an instrument to fine tune prices and inflation levels an absolute impossibility. What Mester is advocating for Fed policy is largely antithetical to any notion of price stability.

That paradox is amplified by Mester’s apparent indecisiveness regarding future shifts in Fed policy.

Following the reports, market pricing in the futures market completely eliminated the possibility that the Fed would be approving any additional interest rate hikes. Moreover, the market is now pricing in the equivalent of four quarter percentage point rate cuts next year, according to a CME Group gauge.

But Mester said she’s reserving judgment on where policymakers go from here.

“I haven’t assessed that yet. Where I think we are right now is we’re basically in a very good spot for policy,” she said.

Comparing the Fed’s position to navigating a ship, Mester said, “We’re at the crow’s nest. What does the crow’s nest let you do? It lets you look out on the horizon and see where the data is coming in, where the economy is evolving. And then we’ll have to see: Is it moving in the way that we forecasted?”

There is, of course, a problem with the “crow’s nest” metaphor: while observations from the crow’s nest does allow one to see navigation hazards while still far off, the Fed and everyone else receives economic data when it is close at hand. The crow’s nest does not help a ship’s pilot navigate among shoals, sand banks, and other hazards close to the ship, and inputs on such hazards give little indication of what lies far off. If Mester is standing up in some economic crow’s nest, she’s in the wrong position to make use of economic data as it comes in, and yet that is exactly what she argues the Federal Reserve should be doing—standing in the wrong position, drawing the wrong conclusions.

One problem with Mester’s view on Fed policy: she fails to acknowledge the growing dichotomy between what the market is setting for interest rates and what the Federal Reserve is setting for the federal funds rate.

Despite all the Fed talk about moving interest rates higher, the only interest rate the Federal Reserve sets directly is the federal funds rate (which is expressed daily in the marketplace as the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, of SOFR). All other interest rates, including Treasury yields, are set by Wall Street.

During the past year, Wall Street has been keeping market interest rates lower than the federal funds rate.

While there was an upward trend in market interest rates during the third quarter of this year, beginning in October market interest rates began declining again, even as the federal funds rate remained unchanged.

Even mortgage interest rates, which had been flirting with record highs, are currently in retreat.

This is steadily becoming more than just a transitory phenomenon, as I observed in a recent article.

This is, of course, the exact opposite of what the Federal Reserve wants to see. It has been raising the federal funds rate over the past year-and--a-half in order to push these market rates higher. The Fed’s strategy to corral consumer price inflation has been to push interest rates higher, and at present they are moving lower.

The irony, of course, is that even though market interest rates have been problematic in their direction and are at present trending down, consumer price inflation itself has been trending down since well before market interest rates began to plateau. Both the Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index have been broadly in retreat since June, 2022.

Incidentally, this decline in the rate of inflation is exactly what the Fed has been wanting to see all along. Not only is Mester not acknowledging the patent inefficacy of the Fed’s interest rate manipulations, but she is seemingly also unaware that disinflation is really happening. Recall her speculation quoted earlier:

“We’re going to have to see much more evidence that inflation is on that timely path back to 2%. But we do have really good evidence that it has made progress and now it’s just, is it continuing?”

We can debate whether the advances are being made “timely”, but there is no doubt that the advances have been made. The October CPI print itself is a strong indication that the advances are continuing to be made.

While neither metric is at the Fed’s target of 2%, for Mester to be uncertain about “progress” in this regard is simply bizarre. By the logic articulated by the Federal Reserve, there has been considerable progress, which a Federal Reserve Bank President cannot see?

The question is still bizarre even when we look at “core” inflation—consumer price inflation with the highly volatile food and energy components stripped out. While core inflation is running higher in both the CPI and the PCEPI, they are both well below where they were in June of 2022.

Are the declines “timely”? That’s a subjective question and different people will have a different answer. The declines are not immediate, which means they are already too slow for anyone’s preferences, all things being equal, but they are occurring.

Moreover, we have significant indications outside of interest rates and both the BLS and BEA inflation metrics that the price declines will continue. Even in the face of a renewed war between Israel and Hamas, and even in the face of OPEC and Russia oil production cuts, the price of oil has been declining precipitously of late, to the extent of negating all the price support OPEC has attempted with its production cuts.

Even Russia’s benchmark Urals blend is flirting with sliding below the previously shattered G7/EU price cap.

If the current downward trend in oil prices proceeds apace, before long the entirety of the increase in oil prices since the summer will be unwound, as we can see if we look at oil prices just over the past six months.

Moreover, oil stocks in the US are on the rise again—and crude inventories broadly move in opposition to oil prices, rising when oil prices fall and falling when oil prices rise.

Bear in mind that energy prices play an outsized role in overall consumer price inflation.

Prior to the recent decline in oil prices, as oil was trending up, so too was consumer price inflation. When oil prices reversed, so did consumer price inflation.

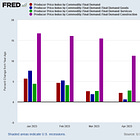

Energy is also a major factor in producer price inflation.

So significant are energy prices on producer prices overall, that in the same month we began to see a precipitous decline in energy prices we saw an absolute drop in producer price inflation, to the extent that “deflation” becomes a not-inappropriate term to use.

While we can debate whether this indicates a “timely” retreat by consumer price inflation to under 2%, there is no debate that the current oil and energy price trends and the current consumer price inflation trends are both on track to pull consumer price inflation below 2% at some point in the relatively near future.

Indeed, the question is not whether the CPI will drop below 2% change year on year, but whether it will stop dropping once it does. Given the inability of the Fed to sustain market interest rates, even as the Fed shrinks its balance sheet and shrinks the money supply, the evidence may already be indicating the US is about to spiral into deflation. How long the US would stay there is at present still a question, but the risk is definitely there.

Why does Mester not see this and at least mention the risk?

Thus when it comes to interest rates broadly, we are left to wonder: What exactly does Mester want? At what point will she agree with the market place and begin to call for lower interest rates?

Perhaps more crucially, we should ask ourselves if Mester is willing for the Fed to step back and simply let financial markets sort themselves out? The markets have already turned their back on the Fed’s policies vis-a-vis the federal funds rate. With or without the participation of the Federal Reserve, financial markets in the US are going to find their own consumer price, producer price, and interest rate equilibria. Given the pig’s breakfast the Fed has made of things thus far, surely letting the markets run loose to find their own balance is by far the better policy?

Loretta Mester is either not aware of what is happening within the US economy (not to mention the global economy), or for some reason she does not see energy prices as connected to inflation broadly. However, the evidence is abundantly clear that energy prices are falling, energy prices are likely to continue to fall, and energy prices are likely to push overall consumer price inflation down even further.

Loretta Mester seemingly does not know is happening and is unsure of what she wants. She is one of the Fed’s “experts” on all things economic, and she does not know what is happening or what she wants.

Be afraid. Be very afraid.

Here’s a dumb question. Why is 2% inflation a goal? What necessities of the fed or markets does inflation serve?