What Should Be The Federal Reserve Strategy On Inflation?

A Thought Experiment On What I Would Do If I Ran The Federal Reserve

I begin with a shoutout to subscriber UM Ross, who earlier this week asked a damn good question.

"Now if only the Federal Reserve can catch a clue and craft a new strategy on inflation."

What should that strategy be? If you were given absolute power over Fed policy, what would you do?

While it is easy to point out how the Federal Reserve’s current strategy is not working on inflation, at some point the rubber must meet the road of positing what the “correct” strategy on inflation would be.

This is a thought experiment, therefore, on how the consumer price inflation we are seeing today might be constructively addressed by the Federal Reserve. There are, no doubt, many points with which people will disagree, and there are some thoughts that will probably be flat out wrong. Yet if we do not confront the question of what “should” be done, the debate can only move so far forward.

Begin At The Beginning: The Federal Reserve Must Live Up To Its Chartered Mandates.

To formulate an appropriate Federal Reserve strategy, we must first ground ourselves in what is the Federal Reserve’s legally chartered mandates, as per the Federal Reserve Act. Specifically, as regards monetary policy, the Federal Reserve is tasked as follows:

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy's long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.

Arguably, none of these goals have been seriously pursued for quite some time.

We cannot say maximum employment is being pursued when the labor force participation rate has been in overall decline since the late 1990s.

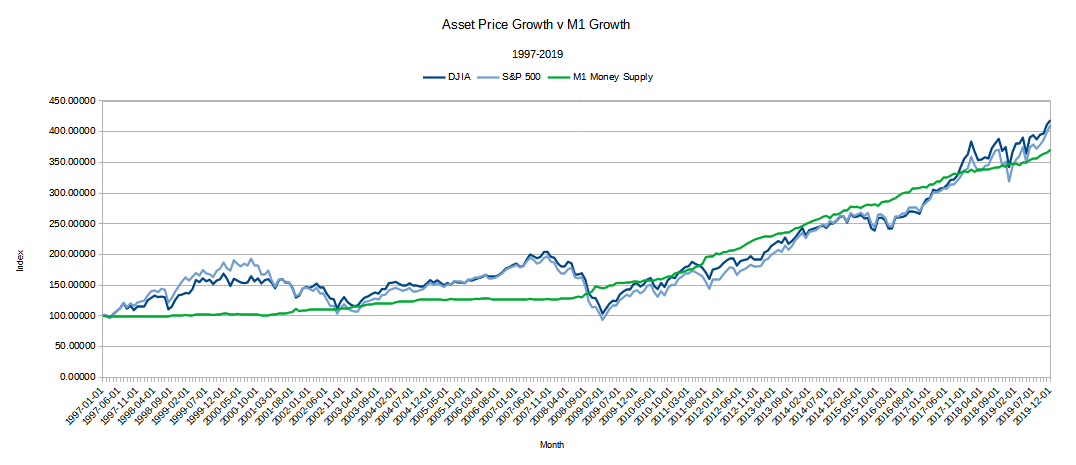

Certainly stable asset prices in financial markets has not been pursued, as I have previously detailed.

Nor can a persistently rising Consumer Price Index be considered “stable” pricing for consumer goods and services.

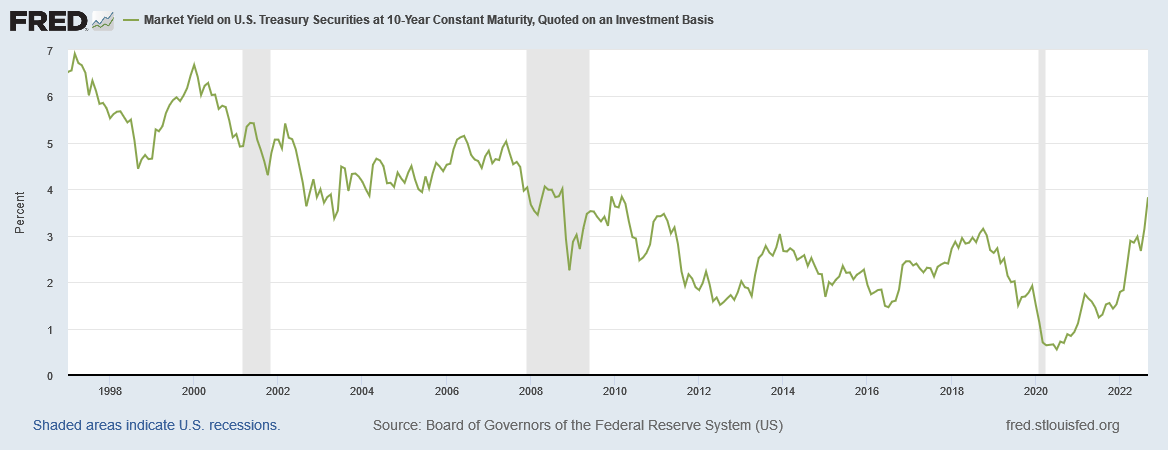

Nor can “moderate” interest rates be deemed to have been pursued during the past decade at least, with interest rates constantly being pushed ever downward.

The objectives for the Federal Reserve’s strategy, therefore, should be to move asset and consumer price inflation trends more towards the horizontal, with interest rate trends also moving towards the horizontal, while avoiding the jobs destruction that excessive interest rate hikes generally catalyze.

How To Get There

If one of the goals is to have moderate interest rates, interest rates have to rise at least somewhat. Additionally, ever since the Volcker Recession, interest hikes have been considered the means for containing consumer price inflation, so stabilizing prices seems to again call for interest rate hikes.

By how much should the Fed raise interest rates?

To arrive at that answer, we have to understand exactly how the rise in consumer price inflation began, and what the drivers of consumer price inflation currently are.

As I noted in an earlier article, much of the rise in consumer prices after the 2020 pandemic-related recession is attributable to the impacts of global lockdowns and the ensuing disruptions of global supply chains.

The lockdowns quite literally reduced available supplies of a number of consumer goods. Essentially, the “Q” variable within the monetarist equation (MV=PQ) was driven towards zero, which necessarily pushes “P” up even with money supply (MV) held constant.

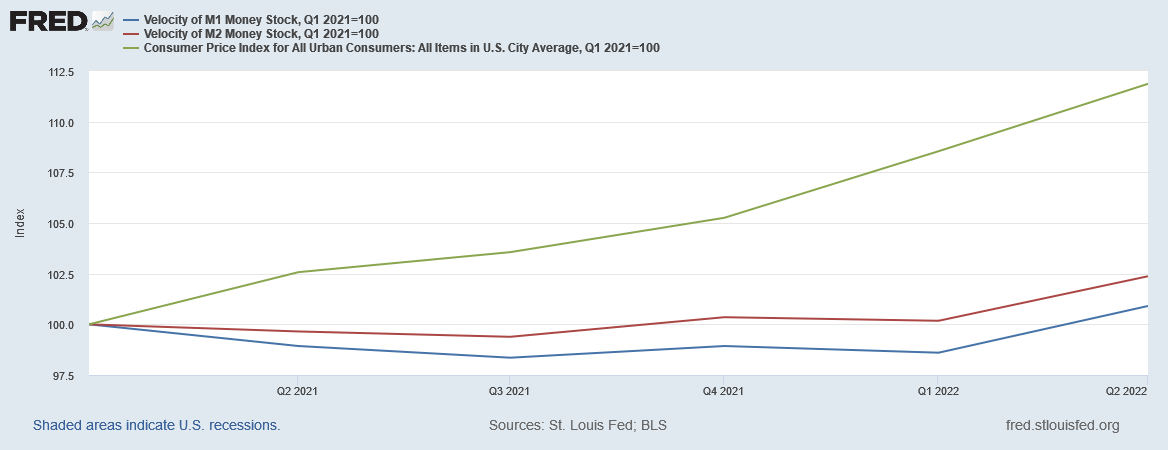

We can begin to gauge the degree to which rises in the CPI are not monetary in nature by comparing the magnitudes of CPI increases against changes in money supply velocity.

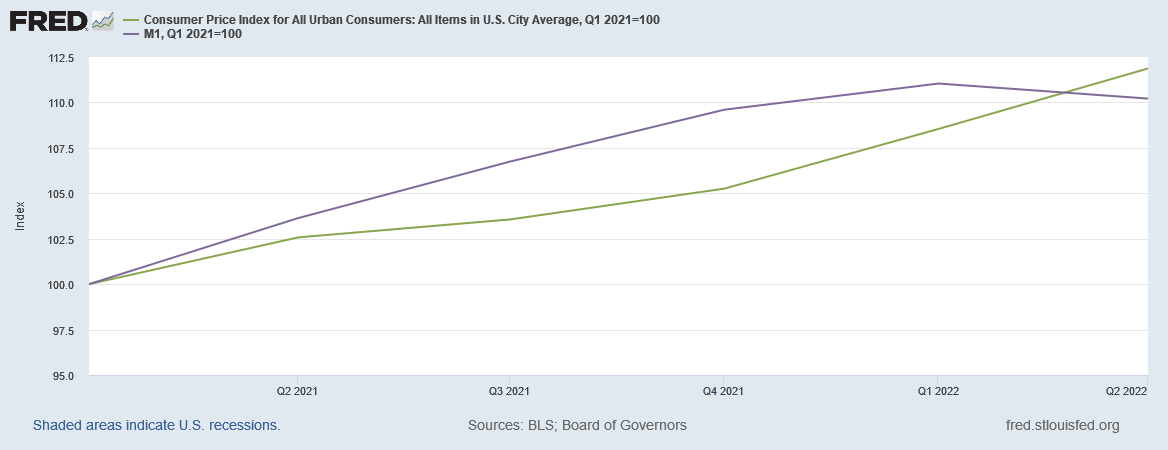

Comparing the magnitude of CPI increases against the growth of the M1 money supply also shows that money supply growth itself is not the sole driver of consumer price inflation.

Inflation that rises even as the money supply contracts is not inflation that is driven by money supply factors, but is instead a product of supply side factors—scarcity and various supply shocks. Merely raising interest rates and shrinking the money supply are not going to impact consumer price inflation that is driven by scarcity and exogenous supply shocks.

At the same time, there is an object lesson to be drawn from the recent BoE capitulation on monetary policy to stave off an apparent meltdown of UK pension funds, driven by a spike in margin calls catalyzed by a spike in yields of long-term British gilts (equivalent to US Treasury notes and bonds)—the vulnerability within financial markets to rapid rises in interest rates once again is found in the boogeyman from the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, derivatives.

Once again, derivative investments notionally structured to reduce investment risk actually increase investment risk.

Simon Wolfson, chief executive of retailer Next, said there were still questions to be answered about the plumbing of the pension fund system and, in particular, the use of LDIs.

The chief executive said the retailer’s own pension scheme had refused to use LDIs amid fears that could lead to increased risk. He said the company’s treasurer had even written to the Bank of England several years earlier to warn about the impact the contracts could have on financial stability.

As financial Substack writer Quoth The Raven has opined in the aftermath of the BoE intervention, the likelihood that US investment funds are similarly exposed through derivative investments cannot be ignored.

Fortunately, the Fed need not ignore these risks. The Fed already has regulatory authority to monitor a number of large financial institutions, and to conduct “stress tests” to ensure they are adequately capitalized to withstand various macroeconomic shocks. With US commercial banks holding trading assets including various derivative instruments in excess of $1.8Trillion, the Fed has the means both to assess the impact of interest rate hikes on derivative investments, including the magnitude of potential margin calls, and the regulatory authority to have financial institutions under their purview organize “Living Wills”—resolution plans for unwinding investments. The Federal Reserve has the regulatory authority within the authorization to require resolution plans from various financial institutions to ensure those plans include necessary steps to address any derivative investments an institution has on its books.

The Fed can also require institutions under its regulatory purview to increase their Common Equity Tier 1 capital ratios based on the results of stress tests and gauge of the risks associated with various assets. Buffering risky derivative investments with greater core capital removes more of the systemic impacts of any liquidity issues that might arise within financial markets as interest rates rise and derivative investments tumble.

Part of what needs to be happening is that derivative investments which are highly sensitive to interest rate rises need to be gracefully unwound as interest rates rise, in order to avoid the sudden margin-call meltdowns British financial markets experienced just a few weeks ago. The Fed needs to use its regulatory powers to ensure this happens, whether by raising capital ratio requirements as rate hikes are implemented, ensuring resolution plans include adequate steps to resolve derivative investments, or some other regulatory mechanism.

If financial writers such as Quoth The Raven can identify the risks attendant upon interest rate hikes, so can the Federal Reserve. That they are apparently not doing that is an appalling lack of comprehensive planning on their part.

Multiple Tools, Multiple Approaches

The essential thrust of an appropriate Federal Reserve strategy to combat rising consumer price inflation is to deploy all the tools in its arsenal, not just interest rate hikes. Ultimately, interest rate hikes should reflect not rises in the Consumer Price Index but the recent rises in the velocity of money. The increase on money velocity is a gauge on the degree to which consumer price inflation is a driven by monetary policy—not a perfect gauge but still a gauge. Consumer price inflation that exceeds increases in money velocity is not going to be very amenable to interest rate hikes, and the Federal Reserve should not seek to resolve such “non-monetary” inflation. Resolving the non-monetary drivers of consumer price inflation falls outside the mandate of the Federal Reserve.

The degree to which consumer price inflation is not driven by money supply and money velocity is the degree to which fiscal policy, rather than monetary policy, must be deployed—and the Fed would be affirming its legal mandates to publicly and repeatedly state as much.

The overarching objective of a Fed strategy should be a systematic, deliberate, and calibrated raising of interest rates to a more “moderate” level, coupled with effective use of capital ratios, financial institution stress tests, and other regulatory mechanisms to ensure markets unwind interest-rate vulnerable derivatives before a margin-call meltdown occurs. Compelling financial markets to move away from interest-rate vulnerable derivatives as an investment strategy also allows the Fed to evade the political pressure to “pivot” away from a tighter monetary policy towards a return to “Quantitative Easing”. Removing the pressure to “pivot” would do much to ensure the Fed’s long-term credibility on maintaining the tighter monetary policies necessary to head off or forestall consumer price inflation that is driven by monetary factors, and thus reduce inflation expectations in the country.

By avoiding interest rate hikes that are in excess of the “monetary” component of current consumer price inflation, the Federal Reserve can at least refrain from the deliberate jobs destruction that it has already acknowledged is part of its current strategy. As the global economy is already sliding deeper into recession, job loss to some degree may ultimately be unavoidable—but to the extent that a global recession is driven by supply shocks and similar forces rather than monetary policy factors is the extent to which such a recession lies outside the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy mandate. What is not driven by monetary factors is not something the Fed should seek to resolve by monetary policy.

Not A Perfect Plan, But Hopefully A Better Plan

I am not going to pretend that I have identified all the relevant issues the Fed should consider while addressing consumer price inflation. I am not even going to pretend that I have the right idea on how to address those issues.

However, the available data on inflation, on money supply, on money velocity, and the Federal Reserves non-monetary regulatory powers clearly shows that the Fed not only has more tools at its disposal than interest rate hikes, but also that it needs to be using those tools. That same data also shows that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policies are not and will never be enough to resolve consumer price inflation within the present circumstances—there are too many aspects that lie beyond the Fed’s legal mandates and authorities for that to be the case.

By aggressively using all the tools at its disposal, and refraining from stepping beyond its monetary policy mandates to address non-monetary consumer price inflation, the Federal Reserve should be able to craft the multifaceted, nuanced, inflation strategy needed to effectively take on consumer price inflation without inflicting unnecessary economic damage.

The Fed can do more than just raise interest rates. The Fed needs to do more than just raise interest rates.

I suppose you're correct in saying that some of the current inflation is due to exogenous factors and thus isn't entirely the Fed's fault, but enabling our government to "borrow" $6T more during the "pandemic" via continued ZIRP was certainly a contributing factor. The classic cause of price inflation is "too much money chasing too few goods." Certainly there's a shortage of certain types of goods, but there's also an awful lot of cash in the system. Ask any real estate agent what percentage of transactions that have been all-cash over the last two year and they'll tell you it's at an all-time high. Where did all that cash come from? Could it be the "easy money" policies that the Fed has pursued for 20+ years, and that they double-down starting in the spring of 2020? ;)

"Regulatory powers"

The Fed certainly has them, but has historically failed to exercise them in a prudent manner. There's a solid argument to be made that if they had done so during the early 2000s, the GFC of 2008 would have been much milder, and things have only gotten worse since then. Before 2008, we had a clean separation between commercial banks and investment banks. That's no longer the case. We "rescued" some of the investment banks by allowing them to merge with commercial banks, while others were allowed to declare themselves "bank holding companies", when by all rights, their investors should have been wiped out. This creates a great deal of moral hazard. Investors get the idea that no matter how imprudently these companies act, the Fed and Treasury will always bail them out. But this is not new; the precedent was set in 1987 with the bailout of Continental Illinois. It's almost like the Fed doesn't really want to engage in prudent regulation of the financial industry. If they were the FDA, I'd say we've got prime example of regulator capture. But the Fed isn't a government agency, the Fed is literally owned by the industry it's supposed to regulate, so expecting them to regulate it in a sensible manner may not be entirely realistic. Now even if they were willing (i.e. if we gave you absolute power over Fed policy), I think it's more than a few years too late to for the Fed to use their regulatory powers to restore sanity and safety back to the financial markets.