Why Seize Maduro? Power, Plain and Simple

Governments Chase Power The Way People Chase Wealth

Lurking behind President Trump’s stunning but successful raid on Caracas to seize, arrest, and extradite Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro is a singular question: Why?

Shoutout to one of my regular readers here on Substack, The Watchman, for putting this question directly:

Peter, I guess my first question would be “Why are we expanding American Power?” To be the “Big Kid” on the block? To take other countries’ oil? Just what is the purpose of Gunboat diplomacy?

Many pundits both pro- and anti-Trump have proffered explanations (or criticisms) of the Caracas raid, all of them proceeding from a particular geopolitical bias.

There are those who focus on Nicolas Maduro being the leader of a sovereign nation.

There are those who focus on Nicolas Maduro having been indicted as a drug trafficker.

There are those who fret about Donald Trump committing the US to yet another exercise in “nation-building”.

While there is some substance in much of what has been said, we also see a hubristic intellectual overreach. What emerges is less an explanation of why Donald Trump would order the Caracas raid and more either a justification for the raid or a condemnation of it. Both normative perspectives, while useful for fleshing out political responses, offer little in the way of substantive understanding.

My assessment of the “why” behind the Caracas raid is far simpler, but I think it is far more complete by virtue of that simplicity.

Governments expand power. Politicians seek power.

When you strip away all the moralizing and political philosophies, that’s what governments do, and have done since the Pharaohs. That’s what Trump has been doing since Day 1 of his return to the Oval Office.

Simply put, governments chase power the way individuals chase wealth.

“Great Power Competition”

The term I broadly apply to this notion is “Great Power Competition”.

Trump’s seizure of Maduro is sufficiently controversial, and sufficiently disturbing to other world leaders, that an exploration of what Great Power Competition is in order. If we proceed from a conceptual framework of Great Power Competition, we begin to see not just why Trump would decide to strike at Maduro, but how that decision reverbates into other geopolitical theaters, such as the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

Starting from the framework of Great Power Competition, we see that this is what nations do, and that the United States is not so different from Russia, China or Iran in this regard.

When I say that the United States is not so different from Russia, China, or Iran with respect to Great Power Competition, I want to be clear that I am not drawing a moral equivalence between these regimes. Quite the contrary, I am very explicitly putting aside all moral precepts and predicates.

When we discuss Great Power Competition, we are discussion what nations—or, rather, governments—do. Whether a particular government’s choice of tactics is moral or immoral is a separate question, and deserves separate treatment. Just as in baseball the pitcher who throws a savage split-finger fastball is as intent on striking out a batter as the pitcher who throws a spitball, the objective is of itself not a commentary on the ethics of a particular approach.

Whether Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is moral or immoral, good or evil, says little about why Putin invaded. Whether Israel’s bombing campaign against Iran during the Twelve Day War was moral or immoral provides no insight into why Israel chose to wage war against Iran.

Likewise, whether there are legal or moral criticisms to be levied against President Trump’s raid on Caracas sheds no real light on why President Trump wanted Nicolas Maduro seized, and why Trump wants regime change in Venezuela.

This is not an exploration of whether Trump’s decision was right or wrong. This is an explication of Trump’s decision as an expression and pursuit of power.

“Great Power Competition” Defined

When defining terms, the simplest and most straightforward definitions are usually the most accessible and therefore the most useful. When we are defining “Great Power Competition”, that is what we should seek—simplicity and accessibility. A good working definition comes from the Department of War:

What’s great power competition? It’s when large nations vie for the greatest power and influence — not just in their own parts of the world, but also farther out.

Bear in mind that "power” itself is fundamentally defined as an “ability to act or produce an effect.”

“Influence” is fundamentally defined as “the power or capacity to cause an effect in indirect or intangible ways.”

Thus, when we are talking about “Great Power Competition”, we are discussing the ambitions of nations to exert power and influence over other nations.

One need only look at the behavior of governments around the world to see that all nations seek to acquire and wield influence over other nations. Just as businesses seek to acquire profit and individuals seek to acquire wealth, governments seek to acquire power. That is what governments do.

We can refine our understanding of Great Power Competition a bit further, however, in order to differentiate between the geopolitical choices made by so-called “great powers” and those made by other, not-so-great powers. “Great Powers” are nations which are going to seek to exert hegemonic influence over other nations. “Hegemony” arises when one entity—typically a nation—is able to exert dominance over others.

Thus, when I speak of “Great Power Competition”, I am speaking of the propensity for various nations to seek, acquire, and wield hegemonic influence over other nations, in either a regional or a global context.

Again, this definition is not an assessment of whether these aspirations by various nations are either moral or immoral. This is simply an understanding of what nations do, for good or for ill.

President Trump Is Explicit: He Wants American Dominance

We do not need to wonder if President Trump has hegemonic ambitions for the United States. He says so quite explicitly, as he did in the press briefing which followed the Caracas raid.

And the Monroe Doctrine is a big deal, but we’ve superseded it by a lot, by a real lot. They now call it the Donroe Doctrine. I don’t know. It’s Monroe Doctrine. We sort of forgot about it. It was very important, but we forgot about it. We don’t forget about it anymore.

Under our new national security strategy, American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again. Won’t happen. So just in concluding, for decades, other administrations have neglected or even contributed to these growing security threats in the Western Hemisphere. Under the Trump administration, we are reasserting American power in a very powerful way in our home region. And our home region is very different than it was just a short while ago. The future will be — and we did this in my first term. We had great dominance in my first term, and we have far greater dominance right now.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the pursuit of dominance as the appropriate geopolitical strategy for the United States, there can be no question that President Trump is pursuing dominance as a geopolitical strategy.

Nor is this a new ambition for Donald Trump. In the first Trump Administration’s 2018 National Defense Strategy summary, one of the base predicates for the strategy hinged on competition among the great powers:

Today, we are emerging from a period of strategic atrophy, aware that our competitive military advantage has been eroding. We are facing increased global disorder, characterized by decline in the long-standing rules-based international order—creating a security environment more complex and volatile than any we have experienced in recent memory. Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.

Former Marine General James Mattis, then Trump’s Secretary of Defense, cast the strategy specifically in terms of Great Power Competition.

“Today, America’s military reclaims an era of strategic purpose, alert to the realities of a changing world,” said Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, according to the prepared remarks of his speech on Friday morning. “We will continue to prosecute the campaign against terrorists, but great power competition—not terrorism—is now the primary focus of U.S. national security,”

Dominance is a theme of several of the items within President Trump’s 2024 campaign platform “Agenda 47”

Make America the dominant energy producer in the world by far!

Stop outsourcing, and turn the United States into a manufacturing superpower.

Strengthen and modernize our military, making it, without question, the strongest and most powerful in the world.

Keep the US Dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

Nor is military muscle the only means by which President Trump seeks to exert dominance in the world. As we saw in the spring with his visit to the Middle East, Trump also seeks hegemonic influence through a combination of diplomatic overtures and trade deals.

President Trump also has demonstrated a measure of hegemonic influence in helping broker a ceasefire between India and Pakistan when their long-simmering dispute over Kashmir flared up once again into outright military aggression.

Donald Trump’s ambition for the United States has been, from the beginning of his first term of office, global hegemony. He wants America to sit at the head of the table.

The United States Is Not Alone

While Donald Trump is not at all shy about stating his ambition for American dominance in the world, we should not presume that he is unique in this regard. He is not.

Israel emerged from the Twelve Day War with unchallenged regional Great Power status in the Middle East. That status was made evident when the new regime in Syria allowed Israeli aircraft transit through Syrian airspace when carrying out strikes on Iran.

For its part, Turkey’s role in helping topple the Assad regime in Syria at the end of 2024 served to launch it also into regional Great Power status in the Middle East.

The rise of Israel and Turkey as regional Great Powers in the Middle East came at the expense of Iran.

With respect to Iran, the aftermath of the Twelve Day War saw China exploit the outcome by agreeing to supply Iran with its domestic version of Russian S-300 air defense system, the HQ-9B.

While the extent to which China is pursuing a hegemonic ambition in Iran is problematic, there is little doubt that China has a clear interest in Iran’s situation, given that China is Iran’s principal buyer of Iranian crude. Moreover, China is also taking advantage of Russian limitations by stepping in to arrange deals for Chinese military hardware when Russia has failed to deliver or refused to commit to delivering key items.

Regional analysts see the fresh HQ-9B deployment as a vivid signal that Iran’s military ties with China are poised to deepen, a trend reinforced by Tehran’s newfound appetite for the J-10C multirole fighter after Moscow repeatedly delayed deliveries of the Su-35.

With Russian influence apparently waning in Iran, China is stepping into to fill that breach. Arms sales are a quick pathway to geopolitical influence for every nation.

That assessment is bolstered by Syria’s broader willingness to engage with Western nations (including Turkey, which becomes “Western” in this regard as a NATO member) at the expense of Russia, formerly one of Assad’s principal backers.

Nations Reach For Power And Influence But Don’t Always Get It

While we can easily see that nations as a rule will reach for at least some measure of power and influence, the reaching alone is no guarantee that power and influence can be achieved.

World reactions to Maduro’s extradition show in stark terms the relative impotence of many global actors with their own global ambitions.

Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, posting on X several hours after the Caracas raid was complete, offered to act as a “mediator” to the “crisis”.

In a statement posted on X, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez called for “de-escalation and responsibility” in Venezuela and for “international law and the principles of the United Nations Charter” to be respected.

The socialist politician said that Spain’s embassy in Caracas and its consulates continue to be operational after the bombings.

Madrid’s Foreign Ministry further said that “Spain is willing to lend its good offices to achieve a peaceful and negotiated solution to the current crisis.”

Exactly what remained to be negotiated was unclear, as everything including the shouting was by that point complete. The “solution” had already been achieved: Maduro was in custody and out of power.

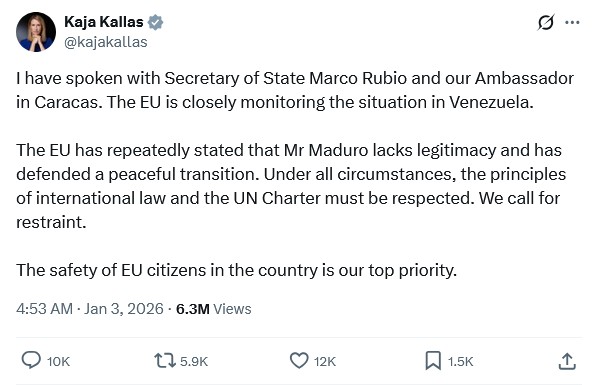

The European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Kaja Kallas, posted on X focusing mainly on the security of EU citizens.

Eugyppius, a Substack writer who focuses on Germany and the EU, savaged the response as “entirely irrelevant”.

Even Russia was left with just powerless and empty posturings, calling on the United States to release Maduro as a “lawfully elected president of a sovereign nation”.

“We firmly call on the U.S. leadership to reconsider this position and release the lawfully elected president of a sovereign country and his wife,” the Russian Foreign Ministry said in a statement, and described that the crisis should be resolved through diplomatic means.

China also was left with issuing similarly vacuous statements.

China has called on the United States to immediately release Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro after Washington carried out massive military strikes on the capital, Caracas, as well as other regions, and abducted the leader.

Beijing on Sunday insisted the safety of Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores be a priority, and called on the US to “stop toppling the government of Venezuela”, calling the attack a “clear violation of international law“.

However, there is zero chance that will happen, as the position of the United States is that Maduro is an indicted drug trafficker, not a lawfully elected president of a sovereign nation.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio threw that gauntlet down during the Trump Administration’s press briefing on Saturday.

Nicolas Maduro was indicted in 2020 in the United States. He is not the legitimate president of Venezuela. That’s not just us saying it. The first Trump administration, the Biden administration, the second Trump administration, none of those three recognize him. He’s not recognized by the European Union in multiple countries around the world. He is a fugitive of American justice with a $50 million reward. Which I guess we saved $50 million.

Rubio’s position is axiomatic to the Trump Administration’s stance regarding Nicolas Maduro. There is no negotiation to be had with such a position—one either agrees with it or one does not.

Rubio issued a flat categorical rejection of any of the claims advanced by China, Russia or anyone else regarding Maduro’s presumed “legitimacy”, or a supposed illegality of the Trump Administration’s decision to go to Caracas to capture him. With that statement, Rubio took all such discussions immediately off the table.

Neither Russia nor China have presented any reasons to take their view more seriously than President Trump’s. If Russia and China thought their statements would carry weight and substance, and be received as expressions of their own geopolitical influence, Rubio has already disabused them of that notion.

Right Or Wrong, This Is How Nations Behave

As I opined to The Watchman in my response to his comment, whether what the Trump Administration has done is good or bad depends primarily on what political outcomes one wishes to see in the world.

Those who view all expressions of US power extending beyond US borders as intrinsically corrupt and evil are going to view the Caracas raid as corrupt and evil.

Those who believe all global actions must be sanctioned by a supranational body—the United Nations or the European Union—are going to view the lack of such sanction for the Caracas raid as proof of the Trump Administration’s basic lawlessness.

Those who want President Trump to aggressively confront whatever threatens America’s interests and people are going to view the Caracas raid as something which was a long time coming, and which should have been done years ago.

Yet what all of these various constituencies need to acknowledge is that, regardless of the particular political or moral lens through which they choose to view Trump’s actions, in all cases they are assessing both the Trump Administration’s expression of geopolitical dominance and its desire to increase that dominance.

Russia and China are perturbed by this action primarily because every such expression of geopolitical dominance by the United States challenges and even diminishes their own efforts at geopolitical dominance.

The member states of the European Union champion rinsing all such actions through supranational bodies because that is the only basis on which the EU itself can have any credibility on the international stage.

Just as people aspire to wealth and businesses aspire to profits, nations aspire to power and influence. Nations with the resources to dominate others aspire to hegemonic power and influence—thus making them “great powers” at either a regional or global level.

In every part of the world, and in every domain of geopolitics and global economics, this is what nations do.

Why did President Trump seize Nicolas Maduro? To both flex and increase American power and influence.

What has President Trump accomplished by seizing Nicolas Maduro? For at least the time being, he has increased American power and influence—in Venezuela, in the Western Hemisphere, and around the globe.

Does that make the seizure justifiable? No. Nor should it. For justification one must overlay whatever notions one has of what constitutes “American interests” and what establishes “right action” in affairs between nations.

Regardless of the justification—or perhaps the lack thereof—President Trump ordered Nicolas Maduro seized to show and increase American dominance in the Western Hemisphere. That is what nations do, no matter what ideological lens one uses to view the actions of various nations.

I think you are substantially correct in your Great Powers Competition theory. I know you have given the matter a great deal of thought, and have the knowledge of history to back your thesis. But I’d like you to consider two other factors which may be very important in this instance.

One is “necessity”. If our financial precariousness depends upon having the world’s reserve currency, then Trump can be persuaded that we “must” have world dominance or the whole house of financial cards collapses. That’s a compelling argument!

The other is “the Art of the Deal”. Trump doesn’t just “do” deals, it’s what he IS. He is thinking several moves ahead, considering all objectives and side benefits, etc. Making deals is what fuels him, what keeps him feeling young. He may be getting just as excited by a spectacular deal as he is by the thought of more power. His military advisors would know. how to manipulate him in this regard.

Thanks for all of your brilliant work, Peter!