China's Real Estate Crisis Has Echoes In US Markets

US Commercial Real Estate Is Showing Same Debt Vulnerabilities As China

China’s ongoing real estate crisis is all by itself an object lesson on why deflation and debt do not mix.

One of the earliest indicators that China was facing a significant deflation crisis was Evergrande’s epic collapse, which began during the summer of 2021.

Even if all of Evergrande’s assets are purchased by China’s SOEs, that would not provide enough cash to make all of Evergrande’s creditors whole; that would not provide enough cash to sustain the many businesses whose existence is threatened by Evergrande’s non-payment of bills. No matter what diktats Xi Jinping issues, without cash, a good portion of Evergrande’s suppliers and creditors will go under.

Now comes news that China’s largest developer, Country Garden, is on the brink of joining Evergrande in the ginormous dumpster fire that is China’s collapsing real estate markets.

The latest major industry player to get into trouble is Country Garden, once China’s largest developer.

Shares in the construction giant have plunged 16% in Hong Kong since Tuesday, after reports by Reuters and Chinese media that it missed interest payments on two US dollar-denominated bonds. Several of Country Garden’s yuan-denominated bonds were suspended from trading in Shanghai and Shenzhen on Tuesday after they dropped by more than 20%.

Yet as much as China’s dysfunctional real estate developers offer teachable moments on deflation and debt, it is also worth noting that, even as Country Garden spirals in to deliquency and collapse, the US commercial real estate market is likewise spiraling into crisis.

The delinquency rate of commercial real estate mortgages on office properties that had been securitized into Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS) spiked to 5.0% by loan balance in July, up from a delinquency rate of 2.8% in April, having now spiked by 2.2 percentage points in three months, by far the biggest three-month spike in the data going back to 2000, and by 3.4 percentage points so far this year, by far the biggest seven-month spike, according to Trepp, which tracks and analyzes CMBS.

While China’s real estate crisis is several orders of magnitude larger than what is confronting America’s CRE markets, the contagion risks of each illustrate the tendency for real estate bubbles to implode in a spectacularly disastrous fashion.

Like China’s bursting housing bubble, the problems in the US commercial real estate market are nothing new. Indeed, some of the earliest indicators that there might be troubles in real estate beyond just China emerged last September, when the Bank of England opted to intervene in UK bond markets to head off a twin liquidity crisis and housing crisis catalyzed by rising interest rates.

The other catalyst driving the BoE intervention was what could be the beginning of a major crisis in British real estate, as soaring yields plus uncertainty over recent budget pronouncements by Britain’s new government under Prime Minister Liz Truss threatened to drive interest rates—and thus mortage defaults—into dangerous territory.

One homeowner told MailOnline: 'Like thousands of others, we’re currently buying a new property and our current mortgage offer expires soon. It's quite possible that we’ll have to pull out of the sale, as I suspect thousands of others will too. That’s because our current bank, HSBC, won’t offer a new product'.

Lenders have also scrapped 1,000 deals in 24 hours with interest rates heading towards six per cent following Kwasi Kwarteng's 'mini budget' last Friday.

There are also an estimated 200,000 so-called 'mortgage prisoners' in the UK who are already on variable rate deals and unable to remortgage.

Much like the bursting of the housing bubble in 2005-2007 in the US, when 45% of mortgage originations were for Adjstable Rate Mortages (ARMs), the relatively high proportion of UK homeowners with variable rate mortgages means the British housing market is facing a wave of potential defaults as homeowners can neither make payments once their mortgage interest rate resets nor refinance their property to at least kick the mortgage interest rate can down the road a few years more.

When the mini-banking crisis erupted in March, with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the risks and problems facing US commercial real estate were placed in sharp relief.

The main catalyst in US real estate woes has been the same one that has challenged Evergrande and now Country Garden in China: debt financing/refinancing difficulties.

The second factor is that corporate interest rates—just as with treasury yields, began rising even before the Federal Reserve began hiking the federal funds rate in March of last year. Effective yields on BBB-rated corporate debt (the lowest “investment grade” debt rating) are higher now than at any time since July of 2010 (with the exception of brief spike during the dislocations of the government-ordered 2020 recession).

These two factors combined present a major hurdle for refinancing of commercial real estate debt, which means that, as that debt matures, it must either be repaid or there will be a default.

Whereas in the US Jay Powell’s jawboning is to blame for making debt more scarce for real estate investments, in China real estate developers were suddenly confronted by Xi Jinping’s “three red lines”, which drastically limited their ability to debt finance their projects.

The rotten foundations of China’s real estate sector were unintentionally revealed when Xi Jinping rolled out his “three red lines” to force property developers to de-leverage, and to end speculative housing purchases. Unfortunately for Xi, when the developers began to deleverage, they suddenly were left without the necessary funds to complete many of their housing projects—projects where the individual housing units had already been sold, with Chinese citizens taking out mortgages (and paying 100% of the purchase price in the process) on homes that had not yet been built.

When real estate investments float on a sea of debt, and refinancing ceases to be an option, the value of said investments tends to sink rather precipitously, and default on the existing debts tends to rise, also precipitously.

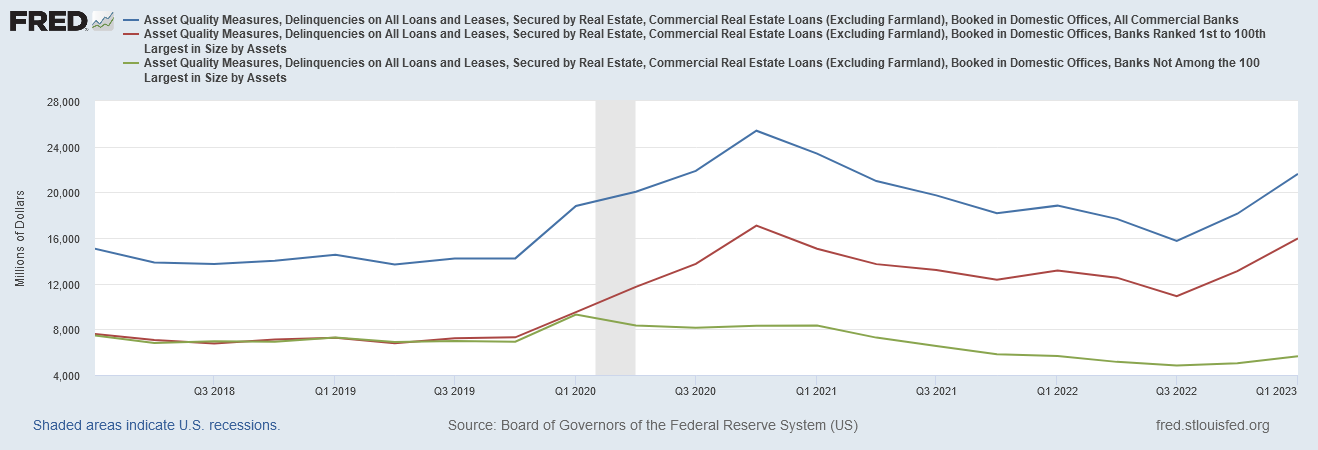

Certainly we are seeing this in the US CRE markets, with delinquency rates on real estate loans rising significantly since the third quarter of last year.

Moreover, Wall Street has been keenly aware of the problem, as the value of Exchange Traded Funds focused on Commercial Mortgage Backed Securities (CMBS) have declined steadily since the beginning of 2022—more or less concurrent with rises in yields.

Intriguingly, while China’s real estate crisis is impacting some of that country’s largest non-bank companies, in the US the problems are impacting mainly the banks, and the regional/local banks in particular.

Early last week, Moody’s placed several banks on credit watch while lowering the credit ratings of several more, primarily owing to their levels of stress over CRE debt.

“U.S. banks continue to contend with interest rate and asset-liability management (ALM) risks with implications for liquidity and capital, as the wind-down of unconventional monetary policy drains systemwide deposits and higher interest rates depress the value of fixed-rate assets,” Moody’s analysts Jill Cetina and Ana Arsov said in the accompanying research note.

“Meanwhile, many banks’ Q2 results showed growing profitability pressures that will reduce their ability to generate internal capital. This comes as a mild U.S. recession is on the horizon for early 2024 and asset quality looks set to decline from solid but unsustainable levels, with particular risks in some banks’ commercial real estate (CRE) portfolios.”

It is not hard to understand Moody’s concerns. Debt default on commercial real estate loans has been rising in recent quarters.

Paradoxically, most of the debt delinquency is occuring among America’s larger banks, even though commercial real estate loans are concentrated primarily among the smaller banks.

This is happening even as small banks hold a larger percentage of their total assets in commercial real estate loans than larger banks—30% to 7%.

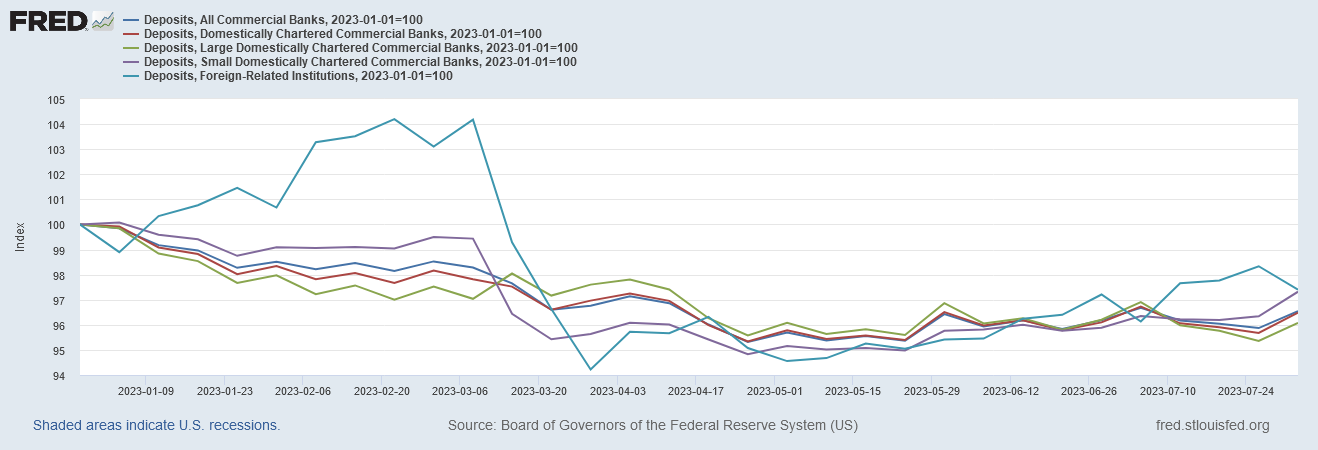

Whether the increase in CRE debt delinquencies will precipitate a fresh banking crisis is still indeterminate. While on the one hand increased debt delinquencies can place liquidity stress on a bank’s remaining assets, for the present at least banks are succeeding in retaining and even increasing customers’ deposits.

So long as there is deposit inflow rather than outflow, banks are unlikely to be pushed into a liquidity crisis. It is interesting, however, to note that small banks are seeing almost as large an amount of deposit inflows as the larger banks in the US.

At least recently, Americans seem to have greater faith in the smaller banks than the larger ones—a judgement that may prove prescient if the trends in real estate debt delinquencies as being concentrated in the larger banks continues.

We should be mindful, however, that the comparisons between debt delinquencies and deposits is an imperfect one, as debt delinquencies are delineated between the 100 largest banks and everyone else, while deposits are delineated between the 25 largest banks and everyone else. Consequently, there is some overlap between the “large” banks regarding debt delinquencies and the “small” banks regarding deposits. However, outside of that overlap, the perception of US banks is that smaller is safer, based on where the deposits are flowing.

Two different countries, two different economies, two different real estate markets, all with one common denominator: a dramatic shift in the debt availability and access.

Whether one examines Japan’s slide into its “lost decades” of stagnation and deflation, the 2007-2009 Great Financial Crisis, the bursting of China’s real estate bubble, or the mini-banking crisis of this past spring, what has catalyzed each of these crises is the inability of the primary actors in the real estate markets to access debt financing at the same interest rates (and therefore financing cost) as before. When real estate developers and investors are dependent upon debt financing to sustain their various operations, any significant loss of access to debt financing disrupts the entire market, and can bring the entire sector crashing down like a house of cards.

Indeed, when a real estate market—any real estate market—is predicated on debt, a house of cards is truly all that it is.

We have been watching the serial collapses of China’s property houses of cards, from Evergrande to Country Garden. We should be mindful as well of the houses of cards closer to home, which are also teetering on the brink of collapse.

CRE debt defaults have not yet produced a banking crisis in this country, but the key word here is “yet”. If debt yields move higher (which the Federal Reserve would like very much), if mortgage rates move higher (which they have been), then more and more CRE debt will become delinquent and slide into default, and the closer the debt houses of cards will come to total collapse.

If/when those collapses do come, they will most assuredly bring a fresh banking crisis with them. When that happens, the US CRE crisis will begin to look an awful lot like the Country Garden crisis in China today—big, messy, and sure to get bigger and messier.